A traditionalist shines through Mexico’s fresh new face

MEXICO CITY — They elected a youthful president, a self-styled defender of democratic principles who promised to bring the country up to 21st century standards.

But many Mexicans suspected that an old-fashioned dinosaur heart was beating beneath Enrique Peña Nieto’s smartly tailored suits, an inheritance from his Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, whose top-down, quasi-authoritarian rule defined much of Mexico’s 20th century history.

On Sunday, after 100 days of living under Peña Nieto’s rule, the Mexican people have a better idea of the ways in which their 46-year-old president, and his vintage political party, plan to manage the future of the United States’ southern neighbor, a country rife with promise and peril. They are also discovering that Peña Nieto may be a kind of hybrid political creature, intent on effecting change while hewing to some of his party’s older ways.

Most significantly, Peña Nieto has begun aggressively pursuing a reform agenda with the aim of transforming Mexico’s woefully underperforming education and tax-collection systems, opening the highly concentrated telecommunications industry to greater competition and allowing the lumbering national oil company to make use of foreign investment and expertise.

The idea is to supercharge the Mexican economy, which has performed competently, if not spectacularly, through six bloody years of war against the country’s organized crime groups. On paper, at least, the proposed reforms would also clear out some of the nation’s institutional rot — statist, monopolistic, and often corrupt — that is a legacy of the PRI’s heyday, which ended in 2000 with its first presidential defeat in 71 years. Peña Nieto is the first PRI president since then.

But as he promises to modernize, Peña Nieto’s moves to centralize power and co-opt opposition forces are causing jitters among those who remember when the PRI ran Mexico as an essentially one-party system. His strategy of de-emphasizing the plague of violence in the national conversation — to make room for a discussion of economic issues — has also stirred fear that the PRI, traditionally well versed in the arts of propaganda and coverup, might be trying to hide the country’s crime problem instead of solving it.

Some worry that Peña Nieto’s team may not be able to formulate a broader security strategy that truly works. The newspaper Milenio counted 2,882 deaths linked to organized crime in Peña Nieto’s first three months in office.

“They are playing media games by not talking about the topic, but the topic hasn’t changed; we keep having this serious problem with violence,” Maria Elena Morera, president of the Mexican civic organization Common Cause, said last week.

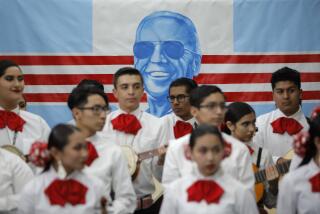

Mexicans are by now used to a kind of throwback quality in Peña Nieto the man: He is reserved and formal in his public manner, with a trademark pompadour that would not be out of place in a 1940s movie magazine. As a candidate, he ran as a pragmatist; as a leader, he tends to speak clearly and forcefully, eschewing flowery phrases for simple descriptions of his plans.

Those plans are ambitious: Peña Nieto’s team has already orchestrated passage of a nationwide education reform law, which required a change in the federal constitution. When the powerful leader of the national teacher’s union, Elba Esther Gordillo, opposed the reform, she was arrested on suspicion of embezzling tens of millions of dollars from union coffers.

The day after the arrest, Peña Nieto went on television and spoke as if heralding a new day for his notoriously corrupt country, announcing that “no one is above the law.” But the arrest was widely interpreted here as a classic PRI power play, one that removed a rival who was an impediment to the party’s broader goals.

The education reform and the general outlines of the other key changes were contained in a blueprint for the country’s immediate political future called the “Pact for Mexico.” It was signed by the leaders of the PRI and the two major opposition parties — both of which had emerged from the presidential campaign weakened and in disarray — in a declaration of unity unprecedented in recent Mexican politics.

Peña Nieto appears to have solved another set of problems within his own party last weekend, when, at the PRI’s national convention, members agreed to change the party’s bylaws to allow for foreign investment in Petroleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, the state oil company. (The oil industry was nationalized by a PRI president in 1938, and remains a point of national pride.)

To some, these moves were a sign of the PRI’s age-old ability to forge consensus in a fractious country. To others, the changes, along with a number of bureaucratic reorganizations by Peña Nieto’s team, hinted at a buried PRI yen for centralized power, headed by an all-powerful president, that in the past had brooked little dissent.

It remains to be seen whether Peña Nieto can pass the remaining major reforms. Changes to the tax code and the oil industry, in particular, could still face major hurdles from populists, nationalists, leftists and special interest groups.

If he succeeds, and the economy roars, the new jobs and boosted incomes may help solve the long-term security problem: Today, the theory goes, many Mexicans turn to organized crime because they earn so little in the legal workplace.

With the same long-term goals in mind, Peña Nieto has announced a national crusade against hunger in selected regions, though his critics have complained that the areas appear to have been strategically chosen to give the PRI a boost in upcoming regional elections.

Peña Nieto’s predecessor, Felipe Calderon, sent the Mexican military into the streets to keep the peace and confront the drug cartels. Since then, 70,000 people have been killed, thousands are missing, and the military stands accused of numerous human rights abuses. Peña Nieto has said he will keep soldiers on patrol for now. At the same time, he is planning to build a 40,000-member gendarmerie, a new security force that will combine police and military attributes.

It could turn out to be a brilliant strategy, forcing the narcos to confront a group that is better armed than the police, but better trained in investigations than the army. For now, though, the details of the plan remain hazy. The same goes for a number of other security goals the president has laid out.

If he doesn’t follow through, it will amount to another way in which Peña Nieto proves a creature of tradition: Mexican presidents have a long history of making spectacular promises that don’t pan out.

“I think what we’ve seen so far is someone who’s saying the right things,” said Maureen Meyer, a Mexico and Central America specialist at the Washington Office on Latin America. “What we haven’t seen is many specifics, or any real changes in practice.... It’s urgent to see some more details about what the shift in his security strategy will really be.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.