Honduran migrants: 'We left because we had to'

- Published

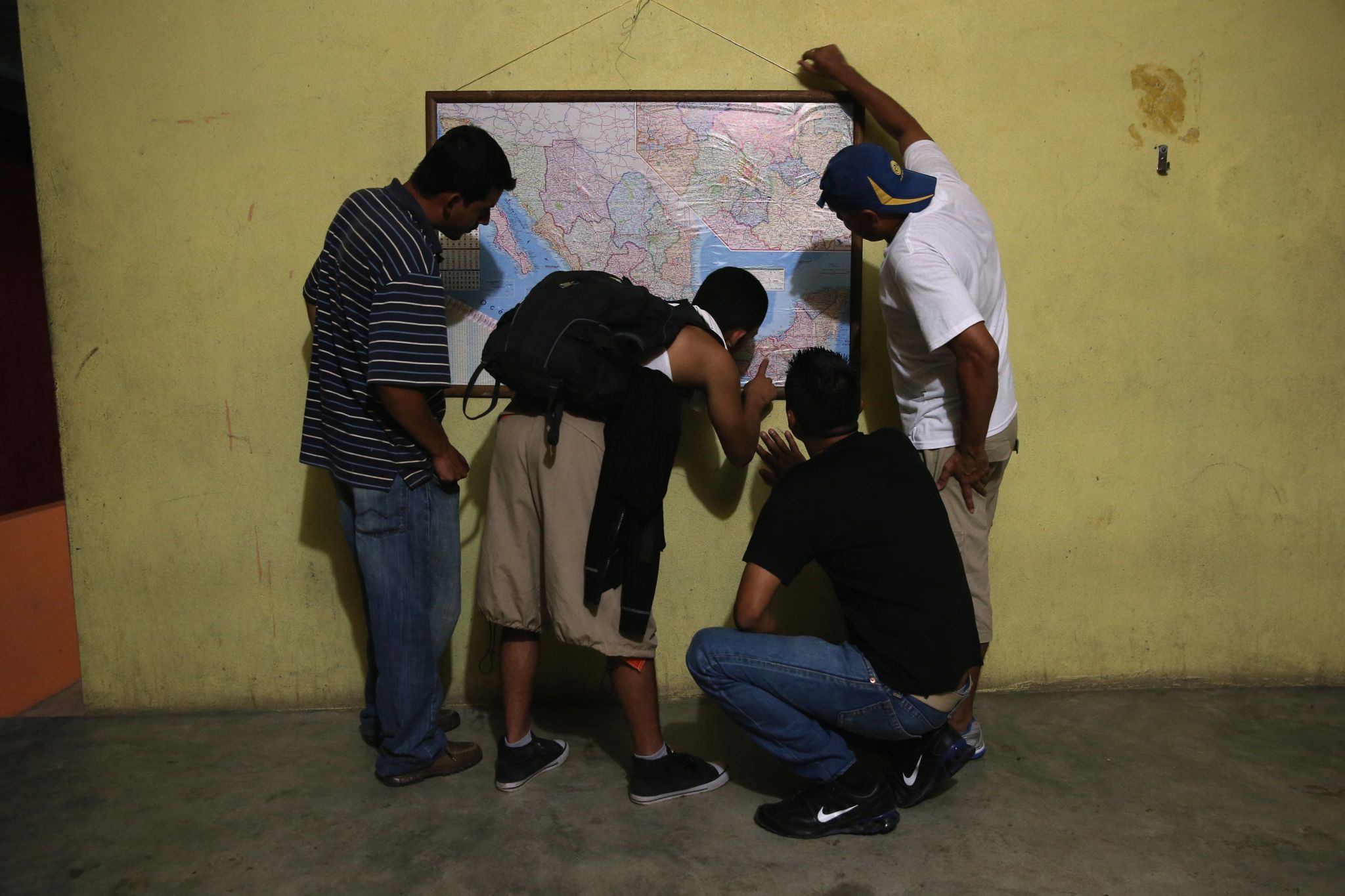

Hundreds of thousands of migrants cross Mexico each year trying to reach the US

Mexico estimates that more than 400,000 undocumented migrants try to cross its southern border every year. Many get stopped and deported, but who are they and why are they leaving their homes?

Josefa is a grandmother of four who first tried to flee Honduras and travel to the United States with her family four years ago.

"We went because we had to go," she says, explaining that her daughter was kidnapped and raped in their native Honduras.

The daughter survived but was determined to leave for the US following her ordeal.

The family was detained in Mexico and sent back for not having a visa that allowed them to stay.

After two more unsuccessful attempts, Josefa gave up.

Her daughter persisted and finally made it to the US only to be detained for being undocumented.

Josefa, who looks after her daughter's children, has not heard from her in months.

Harsher controls

Josefa is one of the growing number of Central Americans trying to flee violence in their home countries for the US by travelling north through Mexico.

In order to halt this tide of migrants, Mexico introduced the Southern Border Programme in 2014.

It increased security and checks along Mexico's southern border, which has led to a greater number of migrants being stopped.

The number of undocumented migrants caught after crossing the border more than doubled between 2013 and 2015 - from almost 87,000 in 2013 to 200,000 - according to the Washington Office on Latin America (Wola), external, a human rights group.

Critics say harsher controls have led to unfair and sometimes violent treatment of migrants.

"Mexico keeps prioritising deportations over protecting migrants who might be fleeing danger," says Wola's Maureen Meyer.

"Hardline policies have proven ineffective at deterring migration, have violated human rights, and have exposed migrants to abuses, corruption, and violence," she adds.

'Returning to nothing'

It is a feeling shared by those who work with deported migrants.

The freight train known as "La Bestia" (The Beast) used to be a popular way for migrants to cross Mexico but due to increased controls, migrants are taking other routes now

Every week, Mexican border control return several busloads of migrants, many of them children, to Honduras' industrial capital, San Pedro Sula.

Vivian Fajardo is a psychologist who works at Casa Alianza, one of the shelters in San Pedro Sula to which the migrants are taken.

She says there is little empathy for the returned migrants.

"Few understand the truth, the sadness, the uncertainty of going, then being detained and returned to Honduras and returning to nothing."

Carlos Flores Pinto, also of Casa Alianza, says the increased controls mean that migrants are being apprehended earlier into their journey.

"People who have tried two, three, four, five times [to reach the US] say that whereas before they used to get as far as four hours from the US border, now they don't even get to Veracruz."

Refugee problem

With the route to the US becoming ever more difficult, an increasing number of people are applying for asylum in Mexico.

Central Americans are increasingly seeking asylum in Mexico

According to the United Nations' refugee agency (UNHCR) applications have risen almost tenfold in the past five years.

"Increasingly we're talking about a refugee problem in the region and not only a migration issue," says UNHCR Mexico representative Mark Manly.

Neither Mexico's interior ministry nor the National Institute of Immigration would grant the BBC an interview.

But in September, Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto acknowledged the problem in a speech at the UN.

"In Central America, the violence generated by organised crime (...) is displacing entire communities, pushing thousands of people to abandon their countries," he said.

He also revealed a plan to improve matters, including strengthening Mexico's refugee recognition procedures and "developing alternatives to immigration detention for asylum seekers".

'Empty promises'

But for Sister Magdalena Silva Renteria, who runs the Cafemin migrant shelter in Mexico City, these are empty promises.

"There's a big difference between talking the talk and walking the walk. We live the reality with the migrants. [President] Pena Nieto doesn't have a clue," she says.

Cafemin opened in 2012. Back then, it looked after 10-15 migrants at a time. Now it houses as many as 70 people.

Juan, 22, is one of them. He travelled from Honduras to Mexico City with his wife, their five children and his wife's parents.

Juan travelled to Mexico with his five children, including baby Alison

He says he had no option but to leave Honduras. "If you work, the gangs wait for you on your way home and assault you," he says.

"It was either stay and die or leave the country."

The first time he left Honduras bound for the US, he was caught in Mexico and deported.

This time he hopes to stay in Mexico City and apply for asylum with his family.

There are many others like Juan and with violence in Central America showing little sign of abating, his future and that of those like him remains uncertain.

- Published28 October 2016

- Published21 October 2016

- Published18 February 2016