When protesters flooded the streets of Managua this week, their anger found an unusual target: a garish metal forest of 17-metre (56ft) sculptures known as the Árboles de la Vida.

The multimillion-dollar art project – inspired by the work of the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt – was reputedly inflicted upon Nicaragua’s capital and other cities by first lady Rosario Murillo in an attempt at civic beautification.

For critics, however, the multicoloured structures – more than 140 of which now adorn roundabouts, street corners and parks – have come to symbolize how Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista Front (FSLN) has lost touch with the people in whose name it once fought.

As deadly anti-government protests gripped Central America’s largest country this week – and the death toll reportedly rose to more than 60 – the trees came crashing down.

“Each time a ‘tree of life’ is felled, the people around it cheer and stamp and jump on it,” celebrated La Prensa, a Managua-based opposition broadsheet.

For Ortega, a one-time revolutionary icon who has towered over his country’s politics since the late 1970s, the deadly unrest represents a dramatic reversal of fortunes – not to mention a threat to his rule.

“If I were the Ortega government I would be nervous,” said Geoff Thale, a Central America expert from the Washington Office on Latin America advocacy group.

Tens of thousands have joined student-led protests, which started as an outbreak of fury over social security reforms and morphed into a broader revolt against the authorities’ violent response – and Ortega’s 11-year rule. At least forty-two people have died in the unrest, including a journalist shot dead while broadcasting on Facebook Live.

“We came in memory of the university students who fell fighting a dictatorship,” said Cinthia Madrigal, 30, who joined a march in Managua. “We took to the streets peacefully … and Daniel ordered us to be killed.”

During the 1980s, Ortega became a poster boy for the global left: a mustachioed Marxist feted for overthrowing the despised dictator Anastasio Somoza and for his David versus Goliath cold war struggle with Washington.

Ortega, now 72, suffered a chastening setback in 1990 after losing a presidential election he had expected to walk.

In 1998, his step-daughter – Murillo’s daughter, Zoilamérica Narvaez – publicly accused Ortega of having sexually abused her for a number of years from the age of 12. Murillo chose her husband over her daughter, and gradually moved to the centre of power; both parents deny the allegations.

After two failed attempts to reclaim the presidency, Ortega staged a dramatic comeback in 2006 – a victory in Murillo is thought to have played a key role.

In his victory speech, Ortega pledged to rule for the poor and for the people and “create a new political culture”. Yet he returned a changed and to many a tarnished man.

Former Sandinista comrades began turning away from the Nicaraguan president amid accusations of cronyism and corruption and anger over his support for a highly controversial Catholic church-backed ban on abortion.

International backers including Salman Rushdie and Noam Chomsky denounced his authoritarian tack. One critic accused Ortega, once likened to legendary freedom fighters such as Nelson Mandela, of becoming a Latin American Mugabe.

This week, as the protests gained momentum, Ortega was even compared to Somoza himself.

On the streets of Managua protesters could be heard chanting: “Daniel! Somoza! ¡Son la misma cosa!” – “Daniel! Somoza! They’re the same thing!”

Parallels with 1979 are hard to avoid. Some of the fiercest clashes this week have taken place in Masaya’s indigenous Monimbó neighbourhood, where the first flames of the insurrection against Somoza were lit. Protesters have even appropriated one of the revolution’s most famous slogans: “Let your mother surrender!” and turned it against the former insurgent leader.

In an unflinching editorial La Prensa warned: “Ortega must step down peacefully or he will have to leave as Somoza left.”

Vilma Núñez, a veteran activist who runs the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights, said she believed that as far back as the 1980s the Sandinista movement had begun taking on many of the characteristics of Somoza’s corrupt and brutish regime.

Since Ortega’s second coming, however, the situation had worsened dramatically as he scrapped constitutional term limits and gained a stranglehold on the country’s media. “Ortega has become increasingly authoritarian, concentrating power in himself and those around him,” Núñez said.

Nicaragua has largely escaped the violence which has racked much of Central America, and for a while, Ortega was able to ensure popular support with public works and handouts funded in part by favorable oil deals with Hugo Chávez.

But that economic support has dwindled since Venezuela descended into crisis, and household economies have been squeezed. For many, the final straw was recent social security reforms which increased both employer and employee contributions and imposed a 5% tax on pensions.

Thale said that for all the FSLN’s flaws and its failures to live up to the ideals and policies it once preached, parallels with the Somoza dictatorship went too far.

“I balk a little at saying this is the Somoza regime all over again … [But] I think there are pretty troubling parallels in the situation, and if I were Daniel and the leadership of the FSLN I would be pretty deeply embarrassed by the fact that people can make these comparisons.”

Like Núñez, Thale also saw deep-rooted disillusionment with Ortega’s rule driving the unrest. “People have benefited from populist programs so it is not like he has no support at all. But what I think has been happening over the years he has been in office is that he has grown both increasingly distant from his own broader social base – not just hardcore Sandinistas but popular majorities – and he has worked increasingly both to centralise power and to consolidate his personal and family rule. Discontent with that has been growing … over time and has exploded.”

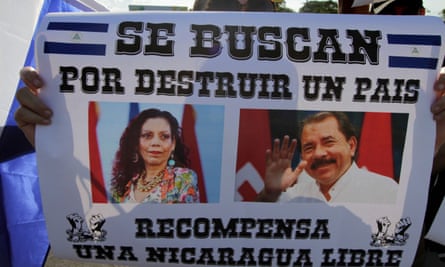

Rosario Murillo, who has described the demonstrations as the work of “minuscule and toxic groups”, was also part of the problem with oddball vanity projects such as the “Trees of Life” fuelling the sense that her septuagenarian husband had lost his way.

Thale said Murillo was increasingly reviled as a calculating, behind the scenes power broker who many suspect is planning to run for president in the 2021 election.

As protests continued to rock Nicaragua this week, the Foreign Office urged British citizens to steer clear of the country. “The situation appears calm but remains potentially volatile,” it said.

Thale also saw rough seas ahead, despite Ortega’s pledge to reverse course on the social security reforms and engage in dialogue that might restore stability.

“Unless people feel like some of their real issues are being addressed I don’t think you can guarantee that social peace will prevail. There is a simmering pot there and they need to take real actions to turn down the heat or it could boil over again,” he said.

During the 1970s, Gonzalo Álvarez was among those who battled to bring the curtains down on the 43-year Somoza dynasty.

This week, the 62-year-old pensioner vowed his latest fight would go on. “Today, the people are demanding justice for their dead, justice for what’s been stolen,” Álvarez said.

“They haven’t understood that we’re a valiant people and that when we decide to do something, we do it.”