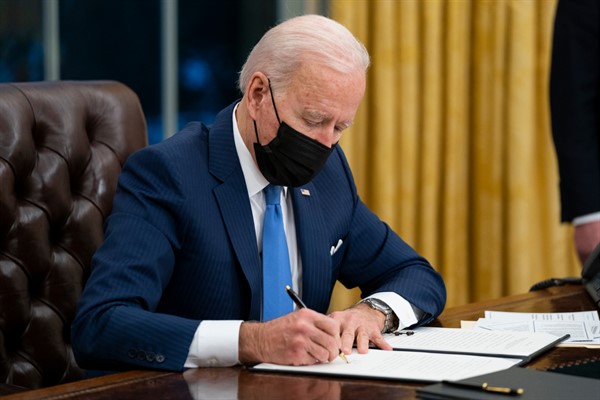

President Joe Biden inherited an immigration system in shambles. After four years of efforts by Donald Trump’s administration to put up as many barriers as possible for migrants and asylum-seekers hoping to enter the United States, Biden’s team must now reopen America’s doors while avoiding a political backlash in Washington. The new administration has also pledged to work closely with Central American leaders to address the root causes of the migrant crisis, though that will be a longer-term undertaking.

This week on the Trend Lines podcast, WPR’s Elliot Waldman was joined by

Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America to discuss the early moves Biden has made on immigration and what his agenda might mean for Central America.

Listen to the full conversation with Adam Isacson on Trend Lines:

If you like what you hear, subscribe to Trend Lines:

The following is a partial transcript of the interview. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

World Politics Review: Where do you see the most far-reaching damage from Trump’s immigration policies, and what will be the most difficult parts of Trump’s legacy for the new administration to address?

Adam Isacson: I think the damage that needs to be undone is mostly to our immigration system, particularly for people who are trying to get protection, people who fear for their lives in their home countries. The idea of asylum, which really came out of World War II, and then was enshrined in the United States in the

1980 Refugee Act, was systematically gutted. The Trump administration was not so efficient at a lot of things; even with building the wall, they really only built it along roughly 250 miles of the border that you couldn’t have walked across before. But in dismantling the right to seek asylum, or otherwise to legally migrate to the United States, Stephen Miller was so single-minded—like an idiot savant who could do one thing really well. And that was to manipulate the administrative levers, change rules and make what were often little-noticed changes, and he really ended up building this entire matrix of blocking foreign people from legally entering the United States.

The New Yorker just had a piece out this first week of February that cites the work of a Harvard professor who has set out his students to document all the changes made in little ways—almost never with the passing of a law, just on their own—to the larger immigration system. They came up with about 1,060 little changes that were made over these four years. So now, the Biden administration has to untangle this web. And meanwhile, you’ve got tens of thousands of desperate people trying to get into the United States to get protection. Many of them are stuck on the Mexican side of the border. So there’s some urgency, even as this entire matrix is just sitting on top of everything.

The damage that needs to be undone is mostly to our immigration system, particularly for people who are trying to get protection, people who fear for their lives in their home countries.

WPR: That urgency is being felt most acutely for the families who have been separated at the border, the asylum-seekers turned back without even being given a hearing and the community leaders here in the U.S., who have been unjustly deported. What recourse is there now, if any, for the people who’ve been affected by Trump’s immigration policies to try to seek accountability and recompense?

Isacson: We’re going to have to start with what is in the Biden administration’s executive orders. Maybe we should just quickly go over what some of those would do, although they often are worded tentatively. The first is to put a 60-day pause on border wall construction while they figure out how to get out of contracts and redirect money. On Feb. 2, a whole bunch of orders came through, and with a whole to-do list of things. One is to set up a task force to reunify families—at least the more than 600 families that remain separated because of the family separation policy that hit its peak in 2017 and 2018. There is going to be a

strategy for heavy investments into Central America, particularly the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, to address root causes of migration. This will probably be more of a long-term approach.

The new administration will be studying how to get rid of one of the main ways since March of last year that the Trump administration stopped any asylum-seeking migration, which was the pandemic order stipulating that, because of health reasons, nobody even gets a chance to ask for asylum and they’re going to be expelled immediately. That’s called Title 42, because of the part of the law that orders it. More than 400,000 people have been very quickly expelled since it was put in.

Then, of course, there is the “Remain in Mexico” program, which sent 70,000 asylum-seekers who are non-Mexican back over the border into Mexican border towns to await their court date in the United States. Basically, they’ve been dumping families without homes, without support networks and without income sources into places like Ciudad Juarez, Tijuana, Matamoros and other often quite dangerous cities. At least a thousand have been documented to have been assaulted, kidnapped and, in some cases, raped. In many cases, they have been robbed while waiting for court dates that just haven’t been coming because of COVID. At this point, at least 28,000 or 29,000 people are still there in these towns awaiting their court dates. In many of the cases that were shut down, there really wasn’t anything resembling due process. So dismantling “Remain in Mexico” is an urgent need.

Another thing that the Biden administration has pretty quickly undone because it was easy to do are the Trump administration’s signed agreements with El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. These are dangerous countries that are sending a lot of people seeking protection, and the signed agreements basically said that asylum-seekers in those countries would need to register their claims there rather than in the United States. These were ironically called “

safe third country agreements.” As of Feb. 5, Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said the U.S. is backing out of those agreements, which is excellent news. So, that’s part of the web. There’s a whole bunch of rules and regulations that Stephen Miller and others put in during the Trump administration that are slowly being dismantled. But as you can see, there’s a long to-do list and the executive orders right now are more a list of intentions than the actual shutting down of these programs. It’s going to be gradual.

WPR: What are some further moves you would like to see now from the Biden administration, especially to address those immediate causes of the backlog and the grievous harm to people who are trying to come here?

Isacson: The biggest one right now in the immediate term is the 28,000 or 29,000 migrants who have been waiting in some cases for a year and a half now in Mexican border cities for their court dates, often in camps or packed into squalid shelters. They should be let in right now. They are already processed, their background has been looked into, and they have a court date. They should be brought into the United States and allowed to be with their families while they await their court dates.

So, that’s pretty urgent. On a slower basis—because it will take time to build up the processing infrastructure under COVID—it is time to undo the Title 42 restrictions for people who are seeking protection. For people who are directly threatened by gangs, or for their political beliefs, or because they’re LGBT, or because they’re being pursued by somebody. They should be let in, regardless of the fact that we are in a pandemic. We just need to have the right health protections, and groups like Physicians for Human Rights and HIAS and others have put out some pretty detailed recommendations for what those health protections would look like.

For years, the image was the United States always bullying and wagging its finger, using the big stick and telling all of these small countries’ leaders what to do. Trump brought that to caricature.

We can do this, and we can do it in a matter of a few months. Right now, the Biden administration doesn’t even really have most of its political appointees in place yet to run this. But it seems like that’s the direction the Biden administration is headed. Of course, they’re probably never going to go as fast as advocacy groups would want them to. But that does seem to be the goal, as of now, speaking in the third week of the Biden administration.

WPR: There was this dynamic that developed during the last administration where Trump dealt with leaders, especially from the three Central American countries you mentioned where the majority of migrants come from, by essentially saying, “Do what you have to do to keep a lid on the flow of migrants coming to the United States. That’s the only thing we care about, and if you do that, we’ll work with you on anything else. And we’ll turn a blind eye to a variety of different problems in the region.” Talk a little bit about the expectations that that has created from leaders in the region who have grown accustomed to being able to flout norms on democratic rights, the rule of law and anti-corruption.

Isacson: This is such an incredible issue. For years, the image was the United States always bullying and wagging its finger, using the big stick and telling all of these small countries’ leaders what to do. Trump brought that to caricature. He was threatening them with everything from tariffs, to aid freezes, to calling them every name in the book, when he perceived that they were not doing enough to keep their own citizens from leaving. It looked like that classic caricature of the big bully from the north. It turned out that the leaders of these three Central American countries—as well as Mexico, to some extent—loved it, because all they had to do was placate him on the migration issue, which is the one thing that really mattered to Trump and Miller. Breaking up a few caravans mostly, and agreeing to these safe third country agreements, which were hardly implemented anyway.

In exchange, U.S. pressure on almost every other issue went away. It was a completely transactional deal. All pressure from the United States on corruption went away, for presidents like Jimmy Morales and later Alejandro Giammattei in Guatemala, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador and Juan Orlando Hernandez in Honduras—none of whom have clean records on corruption, and whose inner circles are believed at least to be part of major graft, if not tied to narcotrafficking. Prosecutors who were trying to do the right thing and clean things up had made big gains, particularly in Guatemala and in Honduras, during the Obama years, but had their legs cut out from under them. There was a U.N.-affiliated prosecutorial mission in Guatemala called the CICIG that put more than 500 people in jail for corruption or organized crime ties.

Jimmy Morales told the CICIG that it had to leave. If the Obama administration—if even the George Bush administration were in power—they wouldn’t have accepted that. But Trump was fine with it. That worked wonderfully to the advantage of corrupt elites in those countries. And when you really follow back to the reasons why so many people are leaving these countries, you do come back to corruption hollowing out institutions, undermining economic growth and allowing gangs to grow enormously in power. So cutting out the anti-corruption effort actually worsened the root causes of migration in these countries, but it worked well for those particular leaders.

The following is a partial transcript of the interview. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

World Politics Review: Where do you see the most far-reaching damage from Trump’s immigration policies, and what will be the most difficult parts of Trump’s legacy for the new administration to address?

Adam Isacson: I think the damage that needs to be undone is mostly to our immigration system, particularly for people who are trying to get protection, people who fear for their lives in their home countries. The idea of asylum, which really came out of World War II, and then was enshrined in the United States in the 1980 Refugee Act, was systematically gutted. The Trump administration was not so efficient at a lot of things; even with building the wall, they really only built it along roughly 250 miles of the border that you couldn’t have walked across before. But in dismantling the right to seek asylum, or otherwise to legally migrate to the United States, Stephen Miller was so single-minded—like an idiot savant who could do one thing really well. And that was to manipulate the administrative levers, change rules and make what were often little-noticed changes, and he really ended up building this entire matrix of blocking foreign people from legally entering the United States.

The New Yorker just had a piece out this first week of February that cites the work of a Harvard professor who has set out his students to document all the changes made in little ways—almost never with the passing of a law, just on their own—to the larger immigration system. They came up with about 1,060 little changes that were made over these four years. So now, the Biden administration has to untangle this web. And meanwhile, you’ve got tens of thousands of desperate people trying to get into the United States to get protection. Many of them are stuck on the Mexican side of the border. So there’s some urgency, even as this entire matrix is just sitting on top of everything.

The following is a partial transcript of the interview. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

World Politics Review: Where do you see the most far-reaching damage from Trump’s immigration policies, and what will be the most difficult parts of Trump’s legacy for the new administration to address?

Adam Isacson: I think the damage that needs to be undone is mostly to our immigration system, particularly for people who are trying to get protection, people who fear for their lives in their home countries. The idea of asylum, which really came out of World War II, and then was enshrined in the United States in the 1980 Refugee Act, was systematically gutted. The Trump administration was not so efficient at a lot of things; even with building the wall, they really only built it along roughly 250 miles of the border that you couldn’t have walked across before. But in dismantling the right to seek asylum, or otherwise to legally migrate to the United States, Stephen Miller was so single-minded—like an idiot savant who could do one thing really well. And that was to manipulate the administrative levers, change rules and make what were often little-noticed changes, and he really ended up building this entire matrix of blocking foreign people from legally entering the United States.

The New Yorker just had a piece out this first week of February that cites the work of a Harvard professor who has set out his students to document all the changes made in little ways—almost never with the passing of a law, just on their own—to the larger immigration system. They came up with about 1,060 little changes that were made over these four years. So now, the Biden administration has to untangle this web. And meanwhile, you’ve got tens of thousands of desperate people trying to get into the United States to get protection. Many of them are stuck on the Mexican side of the border. So there’s some urgency, even as this entire matrix is just sitting on top of everything.