With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since what’s happening at the border is one of the principal events in this week’s U.S. news, this update is a “double issue,” longer than normal. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

CBP reports its March migration data: key trends

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported encountering 172,331 undocumented migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border in March. This mostly happened between the border’s official ports of entry, where CBP’s Border Patrol component had 168,195 “encounters” or apprehensions, a 72 percent increase over February’s total of 97,549. This was Border Patrol’s largest monthly total in exactly 20 years, since March 2001.

Of these 168,195 encounters:

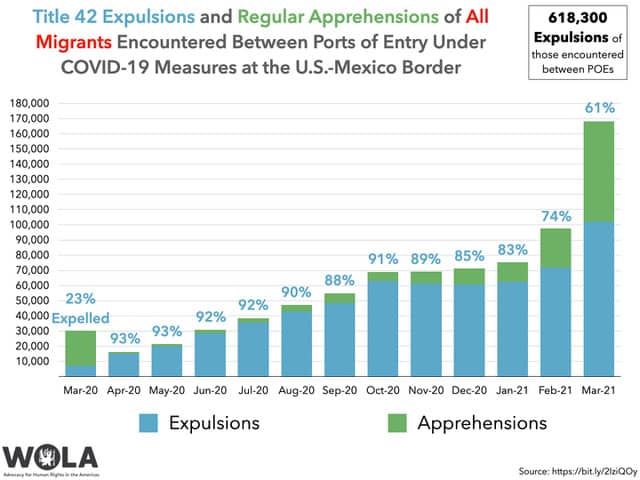

- 101,897 (61 percent) were people who ended up expelled rapidly under the so-called “Title 42” pandemic order issued in March 2020. Mexico has agreed to take Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran migrants expelled back across the border, with some exceptions discussed below.

- About 28 percent were people who had been expelled before, or “recidivist” in CBP’s terminology. This means there is quite a bit of double (or triple) counting, and the actual number of people encountered at the border is smaller.

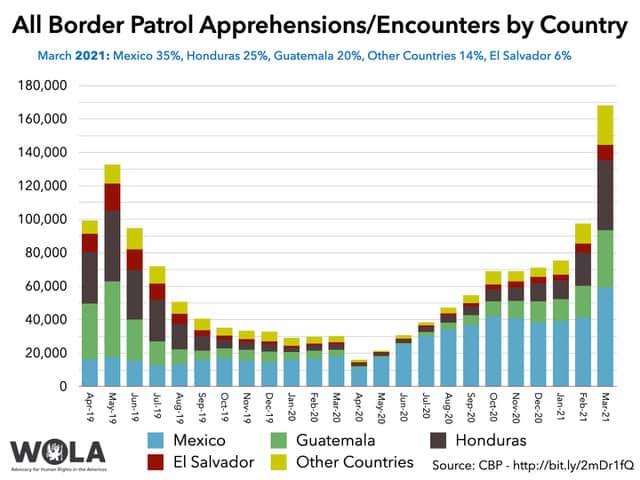

- 35 percent were from Mexico, 25 percent were from Honduras, 20 percent were from Guatemala, 6 percent were from El Salvador, and 14 percent were from other countries.

- This means that in one month, Border Patrol encountered 46 citizens of Mexico for every 100,000 Mexican citizens living in Mexico; 146 citizens of El Salvador for every 100,000 in El Salvador; 194 citizens of Guatemala for every 100,000 in Guatemala; and 429 citizens of Honduras for every 100,000 in Honduras.

- 96,628, or 57 percent, were single adults, a 40 percent increase over February. This is the largest number of single adults in the 114 months for which we have demographic data (since October 2011). 87 percent (84,545) were expelled under Title 42. The majority (57 percent) came from Mexico, 14 percent were from Guatemala, 11 percent from Honduras, 4 percent from El Salvador, and 13 percent from other countries.

- 52,904, or 31 percent, were members of families (parents with children), a 174 percent increase over February. This is the fifth-largest number of family members in the 114 months for which we have demographic data. 33 percent (17,345) were expelled under Title 42. 47 percent came from Honduras, 22 percent were from Guatemala, 8 percent from El Salvador, 4 percent from Mexico, and 20 percent from other countries.

- According to the New York Times, Border Patrol encountered “more than 1,360” family members on March 28 and expelled less than 16 percent (219). On March 26 the agency encountered “more than 2,100 family members and expelled less than 10 percent (200).

- 18,663, or 11 percent, were children arriving unaccompanied by a parent or guardian, a 101 percent increase over February. This is the largest number of unaccompanied children in the 114 months for which we have demographic data, significantly breaking the earlier record of 11,475 set in May 2019. Almost no children (7) were expelled under Title 42, as the Biden administration is refusing to expel children alone without giving them access to protection. 47 percent came from Guatemala, 33 percent were from Honduras, 12 percent from Mexico, 8 percent from El Salvador, and 1 percent from other countries.

CBP encountered 4,136 migrants at its official ports of entry, which are generally closed to “inessential” travel and people without documents under pandemic measures. 73 percent were single adults.

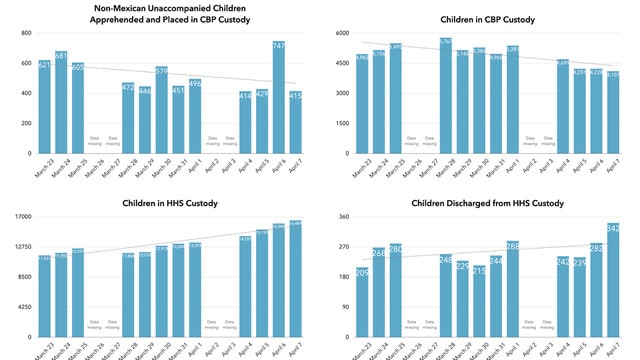

As of April 7, a record 20,596 unaccompanied children were in U.S. government custody. Of these, 16,489 were in shelters run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS), including several temporary emergency facilities set up in recent weeks. The remainder—4,107—are stuck in Border Patrol’s inadequate holding and processing facilities, waiting for new ORR space to open up.

The overall trends for unaccompanied children are promising, though:

- Those newly apprehended by Border Patrol are decreasing, from over 600 per day two weeks ago to an average under 500 per day today.

- Those in Border Patrol custody fell to 4,107 on April 7, from a high of 5,767 on March 28, as more children have been transferred to ORR’s new facilities.

- Daily transfers from Border Patrol to ORR have increased from less than 500 per day two weeks ago, to well over 700 per day on most recent days. Still, a child’s average stay in Border Patrol’s holding spaces is more than 135 hours. The law requires that it not exceed 72 hours.

- As a result, the ORR shelter population of 16,489 represents a huge increase from the 11,551 children in shelters on March 23. ORR is “set to open at least 11 emergency housing sites with 18,200 beds at convention centers, work camps, a church hall and military posts in Texas and California,” CBS News reports.

- ORR seeks to minimize children’s stay in shelters by placing them with relatives or sponsors in the United States, with whom they stay while their needs for protection or asylum are assessed. Transfers out of ORR custody are increasing, but only exceeded 300 per day for the first time on April 7. The number being newly apprehended by Border Patrol still exceeds the number being transferred to families or sponsors by roughly 150 per day.

While the Biden administration is not expelling unaccompanied children under Title 42, it is expelling as many families with children as it can. 80 percent of families Border Patrol encounters are from Mexico or Central America’s “Northern Triangle” (Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala), and Mexico has agreed to take in expelled citizens of the latter countries. Mexico can only take so many, however; as a result—as noted above—about two-thirds of encountered families were not expelled in March.

This contradicts President Biden’s statement at his March 25 press conference that “We’re sending back the vast majority of the families that are coming.” An unnamed Biden administration official—apparently trying to reassure critics—told the Dallas Morning News, “We are doing our best to expel under Title 42 authority, where we can.”

Families whom Mexico does not allow to be expelled get released into the U.S. interior with an order to appear in immigration court. In south Texas’s Rio Grande Valley region, where the largest number of Central American migrants arrive, the demand appears to be overwhelming Border Patrol’s processing capability. The Associated Press reported that “U.S. authorities are releasing migrant families on the Mexican border without notices to appear in immigration court or sometimes without any paperwork at all” in order to save time and ease pressure.

It is not clear which families Mexico will and won’t take back under Title 42. “It doesn’t seem to have rhyme or reason,” Joanna Williams of the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales told the Wall Street Journal, which cited a CBP spokesperson explaining that expulsion decisions “were on a ‘case-by-case basis,’ based on factors including COVID-19 protocols, holding capacity, Mexican law and migrants’ health situations.”

CBP’s data for the fiscal year so far (October-March) show a wide variation across the nine sectors into which the agency divides the border. In the Rio Grande Valley, 32 percent of families get expelled to Mexico. The number is much higher in El Paso (88 percent) or Tucson (76 percent). The Rio Grande Valley may be lowest because authorities in the Mexican state across that part of the border, Tamaulipas, are generally refusing expulsions of families with children under seven years old.

Central American families who do get expelled into Tamaulipas find themselves homeless in one of the most violence-torn states in all of Mexico. A Honduran mother in the Tamaulipas border city of Reynosa, which is disputed by factions of Mexico’s Gulf and Northeast cartels, told the Dallas Morning News that Border Patrol “dropped [her and her child] off at the international bridge into downtown Reynosa at 1 a.m. Several other immigrants said they had been dropped off in the middle of the night, too.” Under non-pandemic circumstances, this would wildly violate the terms of the U.S.-Mexico repatriation agreements, as it represents a grave threat to the migrants’ security. Under Title 42, though, Border Patrol or CBP simply leave the families at all hours in the middle of the border bridge.

At a park in downtown Reynosa about a block from the border bridge, expelled Central American families have begun to congregate around a gazebo. The scene threatens to resemble a recently disbanded tent encampment in the nearby border city of Matamoros, where over 1,000 Central American family members subject to the now-defunct “Remain in Mexico” program lived for over a year. “I have a big concern that the numbers will increase to the point where we have a refugee camp like in Matamoros,” Sister Norma Pimentel of Catholic Charities Rio Grande Valley told the Dallas Morning News.

Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, a cofounder of the “Sidewalk School” that offers lessons to the children of asylum-seeking kids stuck in Mexico, told the Rio Grande Valley Monitor that Reynosa is much more dangerous than Matamoros. While her group accepted U.S. volunteers to support its work in Matamoros, the security situation makes that impossible in Reynosa. “We’re not bringing any Americans into this because of the cartels. We just keep ourselves safe at all times and we keep our heads down and mind our business.”

CNN, meanwhile, reviewed Border Patrol data indicating that many expelled families are separating inside Mexico: Parents are sending their children back across the border unaccompanied, knowing that they will be taken in and eventually placed with relatives inside the United States. The potential number of family separations is jaw-dropping: “From February 24 to March 23, there were 435 incidents in the south Texas region where children were apprehended crossing the border alone after previously being expelled with their family,” CNN reports.

Envoy visits Central America as USAID sends a team

Ricardo Zúñiga, a veteran diplomat who since March 22 has been the State Department’s special envoy for the Northern Triangle, visited Guatemala and El Salvador this week. His purpose appeared to be to get to know some of the key actors in both countries—in government, the judiciary, and civil society—while laying the groundwork for a future U.S. aid package aimed at addressing the “root causes” of migration from the region.

In Guatemala on April 6, Zúñiga and National Security Council trans-border director Katie Tobin met with President Alejandro Giammattei and senior cabinet members, as well as with non-governmental organization leaders and judicial sector representatives, including the country’s special prosecutor against impunity and a judge who has been recognized for her bravery. At a press conference, Zúñiga indicated that, in addition to economic aid and supporting reformers, the Biden administration is seeking means “to create legal means for migration so that people do not have to use irregular and dangerous routes.”

The U.S. envoy’s visit to El Salvador on April 7 was a bit rockier, as the country’s populist president, Nayib Bukele, refused to meet with him. Bukele, who enjoys very high popularity at home, has had chilly relations with the Biden administration and other Democrats:

- In early February, he paid an impromptu visit to Washington seeking to meet members of the new administration, who refused to see him.

- On his busy Twitter account, Bukele has objected to El Salvador being lumped in with its neighbors as a “Northern Triangle” country, arguing that its citizens migrate far less than do Guatemalans and Hondurans. While this is true, 1,570 fleeing Salvadoran children—51 per day—did show up unaccompanied at the U.S.-Mexico border in March.

- Bukele got in an ugly April 1 Twitter argument with Rep. Norma Torres (D-California), the co-chair of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Central America Caucus. Torres told him the migration crisis was “a result of narcissistic dictators like you interested in being ‘cool’ while people flee by the 1000s & die by the 100s.”

- Two of his aides told the Associated Press that “Bukele was angered by State Department spokesman Ned Price’s comments Monday [April 5] that the U.S. looks forward to Bukele restoring a ‘strong separation of powers where they’ve been eroded and demonstrate his government’s commitment to transparency and accountability.’”

Bukele does, however, place a premium on El Salvador’s relations with the United States. Among several contracts with Washington lobby firms is a new one with the law firm Arnold and Porter, signed on March 25: $1.2 million for the services of Tom Shannon, a former ambassador to Brazil and undersecretary of state for political affairs. “President Bukele is the most successful, politically stable and important leader in Central America,” Shannon said in a statement sent to AP.

In the end, Zúñiga and Tobin met with El Salvador’s foreign minister, its attorney general (who is a critic of Bukele), and private sector and NGO leaders.

Honduras was not on the U.S. delegation’s agenda. On March 30 a U.S. court handed down a life sentence for narcotrafficking to Tony Hernández, the brother of President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was named frequently as a co-conspirator in the prosecution’s case. Evidence presented in court pointed to the depth of corruption at the highest levels of power in Honduras. So while the U.S. envoy skipped Honduras during his first official tour of the Northern Triangle, the Hernández government’s foreign minister said that she had a “very fruitful” online conversation with Zúñiga during the week of March 24 and that Honduras’s dialogues with the Biden administration, which “started on February 4,” are “more advanced” than its neighbors’.

The Biden administration faces a conundrum of how to assist countries led by corrupt officials, or what National Security Council Latin America Director Juan González calls “predatory elites.” At his March 25 press conference, President Biden said the U.S government would seek to go around the elites where possible and assist communities directly, arguing that he pursued that approach when he was vice president: “What I was able to do is not give money to the head of state, because so many are corrupt, but I was able to say, ‘Okay, you need lighting in the streets to change things? I’ll put the lighting in.’”

This week we saw signs that the administration’s approach may have a shorter-term, faster-moving component. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) announced that its Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance is deploying a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to the Northern Triangle countries “to respond to urgent humanitarian needs.” A USAID release notes that the agency “has provided approximately $112 million in life-saving humanitarian aid—including emergency food assistance, nutrition services, safe drinking water, shelter, programs to help people earn an income, and disaster risk reduction programs. Of this, $57 million is for people in Guatemala, $47 million in Honduras, and $8 million in El Salvador.”

While much past “root cause” discussions of Central America focused on gang violence and insecurity, the issue of the moment is hunger and severe malnutrition. The pandemic economic depression, two hurricanes in two November 2020 weeks, and a five-year climate change-caused drought, exacerbated by feckless government responses, have brought hunger to emergency levels.

“Guatemala now has the sixth-highest rate of chronic malnutrition in the world. The number of acute cases in children, according to one new Guatemalan government study, doubled between 2019 and 2020,” the Washington Post reported. “In Indigenous communities in the country’s western highlands, where a disproportionate number of people are leaving, the chronic child malnutrition rate hovers around 70 percent, higher than any country in the world.” A World Food Program “March to July 2021 Outlook” report finds 570,000 Hondurans, 428,000 Guatemalans, and 121,000 Salvadorans facing “emergency” or “phase 4” food insecurity. The only level higher is “phase 5,” which it calls “catastrophe,” or famine.

Some border wall construction could restart

Sources at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) told the conservative Washington Times of a conversation in which Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas indicated the Biden administration might allow construction to fill “gaps” in the Trump administration’s border wall.

As a candidate, Joe Biden had pledged that “not another foot” of border wall would be built under his administration. On January 20, he issued a proclamation freezing wall construction for sixty days. That period has passed, and wall construction contractors remain on hold but poised to continue work.

In his conversation with ICE employees, the Washington Times reported, Mayorkas told them that CBP—which manages border fencing—has submitted a plan explaining how it would wish to move forward. “It’s not a single answer to a single question. There are different projects that the chief of the Border Patrol has presented and the acting commissioner of CBP presented to me.”

The Secretary added that there is “room to make decisions as the administration, as part of the administration, in particular areas of the wall that need renovation, particular projects that need to be finished. These could include ‘gaps,’ ‘gates,’ and areas ‘where the wall has been completed but the technology has not been implemented.’”

At a March 17 House committee hearing, Mayorkas had struck a firmer tone. Asked, “Are you going to be asking the president to finish the wall, and the wall that has already been appropriated by Congress,” the Secretary replied, “No, I will not.”

The abrupt January 20 freeze in wall construction has left gaps where the barrier is unbuilt. Environmental groups, community groups, property holders, and Indigenous communities argue that there should be even more gaps, taking down segments of what was already built. This would mitigate environmental damage in fragile ecosystems, reopen wildlife migratory corridors, and protect ancestral and sacred sites. A coalition of 75 organizations (including WOLA) produced a document in February listing priority areas where existing border wall needs to be taken down.

Links

- Protection-seeking migrants aren’t just coming to the United States. In March Mexico’s refugee agency, COMAR, broke its record for most asylum requests in a month, with 9,076. With 22,606 requests in the first quarter of 2021, COMAR is on pace to exceed 90,000 requests this year, breaking its single-year record of 70,440 requests, set in 2019. As recently as 2015, COMAR was getting only 3,400 requests. More than half of this year’s applicants are Hondurans, followed by Cubans, Haitians, Salvadorans, Venezuelans, and Guatemalans. “We don’t know if it’s their first or their second intention” to remain in Mexico, COMAR director Andrés Ramírez told the New York Times. “What we can tell you is that more and more people are coming to us.”

- The Department of Homeland Security is examining 5,600 cases of migrant children with the expectation that it will find “a small number of additional [family] separations on top of thousands that have already been reported,” according to Reuters. “There is also a lot of misinformation in the files—wrong dates, confusion in names, doubled up cases,” an official said.

- Mexico’s immigration authority (the National Migration Institute or INM) has classified for five years its files on the January 22 massacre of 16 Guatemalan migrants, allegedly committed by state police agents, in Camargo, Tamaulipas. Curiously, at the crime scene was a vehicle that the INM (which has gone through numerous corruption scandals and allegations) had seized in a counter-migration operation a few months earlier. Eight INM agents were fired, but now details will not be public until 2026.

- A March 26-29 AP/NORC poll of 1,166 U.S. adults gave Joe Biden a 61 percent overall approval rating, but only a 42 percent approval rating on immigration and 44 percent on border security. Independent voters disapproved of Biden’s performance on immigration by a 37 percentage-point margin (67 percent to 30 percent). 40 percent disapprove of Biden’s handling of unaccompanied children, and 24 percent approve. The New York Times cites a recent Gallup poll in which immigration tied for third place among issues that respondents viewed as the country’s most pressing problem. It was first place for those who identified as Republicans.

- DHS Secretary Mayorkas paid a low-profile visit to El Paso and the Rio Grande Valley this week, speaking with border security personnel and community organizations.

- Asked by Politico what she would like her colleagues to understand about the border, Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who represents El Paso, replied, “Number one, migration doesn’t stop. Number two, deterrence doesn’t work. And number three, the status quo hasn’t addressed anything.” Escobar, a recipient of WOLA’s 2020 Human Rights Award, also gave an interview to the Intercept in which, among many proposals, she called for the imprisonment of former Trump advisor Stephen Miller.

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson