With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since what’s happening at the border is one of the principal events in this week’s U.S. news, this update is a “double issue,” longer than normal. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Migrant apprehensions may reach largest annual total since early 2000s, even as most are expelled

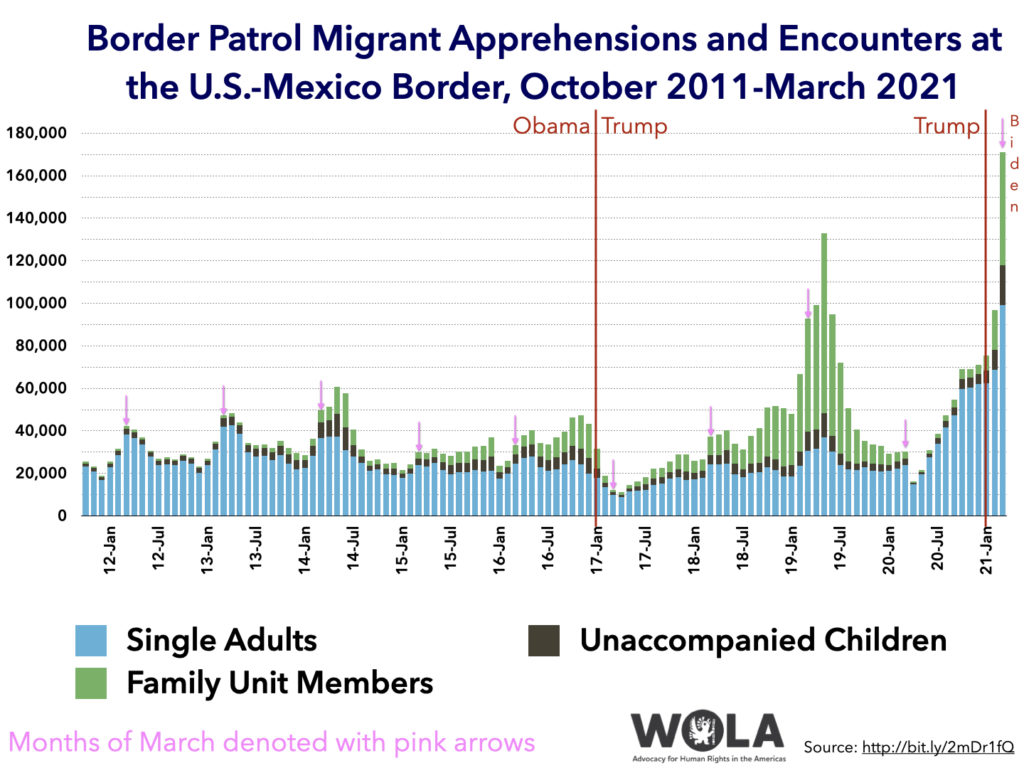

The Washington Post published preliminary data from Customs and Border Protection (CBP) about migrants encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border during March. It shows migrants came into the agency’s custody, at least briefly, on 171,000 occasions last month. That would be the largest monthly total since March of 2001, and a remarkable 76 percent more than February 2021. Here is how it would compare among the previous 115 months:

Of this “preliminary” figure of 171,000:

- 99,200 appear to be single adults, a 44 percent increase over February and the largest number of single adults encountered in the monthly data WOLA has collected, which go back to October 2011.

- 18,800 were unaccompanied children, a 102 percent increase over February, smashing the May 2019 record of 11,861.

- 53,000 were members of family units, a 180 percent increase over February and the fourth or fifth largest monthly total since October 2011.

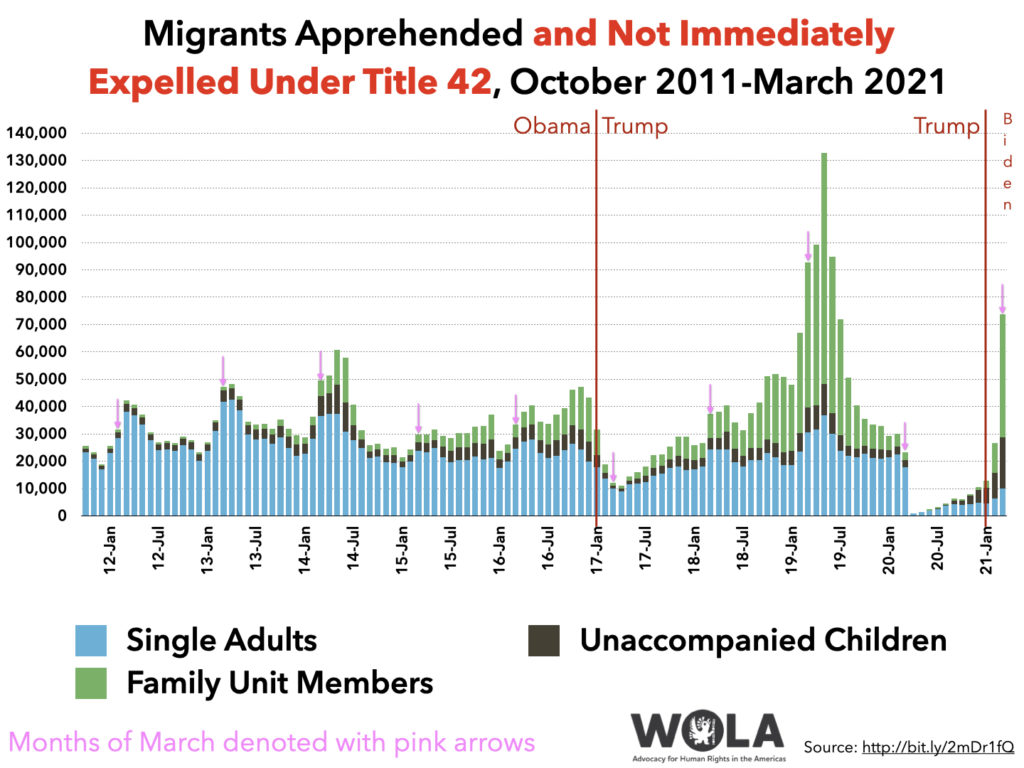

Under the Trump-era “Title 42” pandemic restrictions that the Biden administration has kept in place, about 90 percent of adults and 10-20 percent of family members are being expelled, usually in a matter of hours. So the population of migrants taken into U.S. custody at the border looks more modest:

CNN reported seeing Border Patrol estimates predicting that the agency might apprehend or “encounter” 2 million migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border between October 2020 and September 2021. That number—up to 1.1 million single adults, 828,000 family members, and 200,000 unaccompanied children—would shatter Border Patrol’s annual record of 1,643,679 migrant apprehensions set in 2000.

That estimate seems dubious. Even with 171,000 migrants apprehended in March, getting to 2 million would require Border Patrol to encounter a record-shattering 241,000 migrants for each of the next six months—about 20,000 more than the largest monthly total ever measured. Deputy Chief Raúl Ortiz said on March 30 that Border Patrol expects to encounter “more than a million” migrants in fiscal 2021. That appears more likely, and would be the largest annual total since 2006, exceeding the 851,508 apprehensions reported in 2019.

Unlike past years, a large portion of these migrants—one half to two-thirds, perhaps—would be instantly expelled under Title 42. And much of the total would be “double-counting” as expelled migrants try to cross again. In February, about 25 percent of people encountered at the border had crossed more than once, CNN reports, up from 7 percent in 2019.

While not on pace for a record-breaking year, Mexico reported apprehending 34,993 migrants in its territory between January 1 and March 25, 7,643 or 28 percent more than the same period in 2020. About 55 percent were from Honduras, 29 percent from Guatemala, and 7 percent from El Salvador. Of all migrants, said National Migration Institute (INM) director Francisco Garduño, 4,400 were minors, about 1,200 of them unaccompanied. Mexico’s totals so far this year “roughly mirror the numbers from early 2019, before Trump forced Mexico” to increase apprehensions by threatening to levy tariffs, the Associated Press observed.

Unaccompanied children: flattening out or even declining?

Much media coverage of the border continues to focus on U.S. agencies’ struggle to accommodate the record numbers of children arriving unaccompanied, whom the Biden administration refuses to expel under Title 42. As of March 31, 18,170 children were in U.S. government custody: 13,204 in permanent and emergency shelters run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR, part of the Department of Health and Human Services, HHS), and 4,966 awaiting ORR shelter space while stuck in Border Patrol’s inadequate detention facilities.

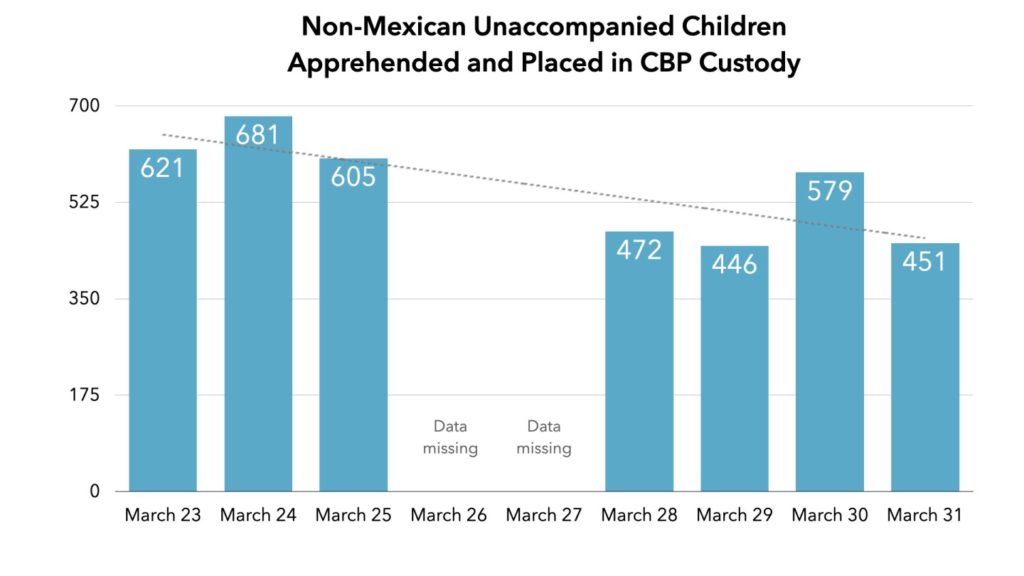

The most recent numbers we’ve managed to obtain do show a glimmer of good news, though, about unaccompanied children. The population in CBP’s custody has dropped under 5,000, from 5,495 on March 25, as new temporary ORR shelter spaces have opened up. And the number of non-Mexican unaccompanied kids Border Patrol is newly apprehending may be dropping. The agency took in more than 600 per day on each of the three days for which we saw data during the week of March 22, but between March 28 and March 31 it took in less than 500 on three of four days, and never reached 600. Though it’s early to be certain about trends, this points to a downward trendline:

The Washington Post, as noted, just reported a preliminary figure of 18,800 unaccompanied children taken into CBP custody in all of March—including Mexican children, who under current law are almost all returned to Mexico. According to the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. government expects to encounter between 18,600 and 22,000 children in April, and between 21,800 and 25,000 in May.

If the lower total since March 28 is sustained, though, unaccompanied child apprehensions will be on the low end, or even below, these estimates. One reason the number of kids arriving alone might decline is the increased probability, discussed below, that a family unit won’t be expelled under Title 42. If there is some likelihood of being released into the interior to pursue asylum, parents will be more inclined to accompany their children, resulting in fewer kids traveling alone.

In fact, Reuters revealed, a surprising number of “unaccompanied” children may have arrived with a family member—but because the adult relative was not a parent or guardian, Border Patrol separated the family. A data project managed by “a handful of nonprofit groups” estimates that as many as 10 to 17 percent of “unaccompanied” children actually arrived with an aunt or uncle, an adult sibling, cousin, grandparent, or other relative. Because they are not immediate family, CBP policy usually considers the child unaccompanied and expels the adult under Title 42. This very high estimate—between one in six and one in ten children separated from a relative at the border—has “not been made public before” and CBP “told Reuters they do not track such separations.”

In the meantime, the large population of unaccompanied kids continues to strain ORR and CBP capacities. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said that CBP is “working around the clock” to move kids out of Border Patrol facilities and into ORR custody as space opens up. This space, as Mark Greenberg notes in a new Migration Policy Institute study, started out very scarce: “The Biden administration took office with less than half of the shelter capacity that ORR had estimated was needed for preparedness.”

Children are not meant to spend a long time in ORR’s shelter network: ideally, no more than about a month. The agency works to identify relatives or other sponsors who can take them while immigration courts rule on their protection needs. ORR has been moving between 200 and 300 children per day out of its system and into relatives’ custody, far fewer than the number of children being newly apprehended and transferred. This points to continued increases in the need for shelter space.

Internal government estimates reported by CNN and the New York Times indicate that ORR could need 34,100 or 35,500 shelter beds to keep up with the high projected number of arriving unaccompanied children. As last week’s update found, a series of emergency shelters—from convention centers to military bases—is increasing ORR’s capacity up to about 28,800 beds. And the New York Times reports that new facilities being “scouted” include “a Crowne Plaza hotel in Dallas, a convention center in Orange County, Fla., and a church hall in Houston.”

This new shelter capacity should alleviate the crowding in CBP facilities’ holding areas, where the law requires children to spend less than 72 hours. Transfers out of CBP custody have increased from about 400 per day the week of March 22 to about 800 per day the week of March 29.

On March 30 CBP allowed selected pool reporters to visit the largest of its holding areas, the temporary processing center in Donna, in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. This site is a complex of tents built in January while a more permanent facility in McAllen, outfitted in 2014, undergoes renovation. The press visitors to Donna found 3,400 unaccompanied children and 700 family members crammed into a space intended for 250. Most children are in eight “pods” separated by plastic dividers, while the youngest are in a “play pen” area where they sleep on mats on the floor. More than 2,000 kids had been in the facility for more than the maximum 72 hours, 39 of them for more than 15 days. Oscar Escamilla, the acting executive officer of Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley sector, told reporters that “250 to 300 kids enter daily and far fewer leave”—a situation that should begin to reverse as temporary ORR shelters come online.

“I’m a Border Patrol agent. I didn’t sign up for this,” the New York Times quoted Mr. Escamilla saying “as he looked at some of the younger children, many of them under 12.” However, as veteran immigration reporter Caitlin Dickerson observed in The Atlantic, even after seven years of child arrivals, CBP has resisted building more family-appropriate holding facilities out of the unproven belief that, as a commissioner told her, “such a project could send a message that would encourage even more people to migrate to the United States.”

The border saw some tragic and outrageous episodes involving children this week. Border Patrol found a mother, her 9-year-old daughter and 3-year-old son unconscious on an island in the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass, Texas. The mother and son were resuscitated, but the girl died. In remote New Mexico desert, Border Patrol night-vision video meanwhile captured smugglers dropping two Ecuadorian girls, age 3 and 5, from atop a 14 foot tall section of border fence. CBP found the girls and “they are said to be in good health,” Al Jazeera reported.

Families: increasing

The category of migrant that appears to have increased fastest in March was family members. Border Patrol reported a 180 percent increase in encounters with families—parents or legal guardians with children—from 18,945 in February to 53,000 last month. The Washington Post noted that DHS officials “are privately warning about what they see as the next phase of a migration surge that could be the largest in two decades, driven by a much greater number of families.”

The Post noted that groups of asylum-seeking families “sometimes collectively numbering as many as 400” have been “showing up this month along the riverbanks in South Texas.” El Faro published a series of photos showing what these nighttime arrivals look like, as Border Patrol has set up card tables on a dirt road in Roma, Texas, at which they check in new arrivals.

What won’t be clear until we see CBP’s detailed March data is how many of these families were allowed into the U.S. interior to begin removal and asylum proceedings, and how many were expelled under Title 42. Under the pandemic expulsions policy, Mexico agreed in March 2020 to take back citizens of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras apprehended at the border. It is still taking back nearly all single adults, who are the majority of all apprehended migrants. But even as it takes a larger number of expelled families than it did in 2020, Mexico appears to have hit a ceiling and is now refusing about 80 to 90 percent of family expulsions, especially of those with small children, according to the Washington Post. (That article’s co-author, Nick Miroff, notifies us that the percentage more recently appears to have fallen to 75 to 80 percent—perhaps due to U.S. requests that Mexico take more expelled families.)

In order to get around this, DHS has been flying some families from segments of the border where Mexico is refusing expulsions to segments where Mexico is still accepting them. Planes continue to arrive daily to El Paso, where El Paso Matters has documented the anguish of parents with small children taken from the airport to the middle of the border bridge and left in Ciudad Juárez.

Garduño, the director of Mexico’s INM, told press that smugglers are advising would-be migrants to bring children. They “suggest that migrant parents travel with their children ‘to facilitate entry into Mexico and the United States.’”

Families often get to remain in the U.S. interior for a long time as badly backlogged U.S. immigration courts consider their requests for asylum or other protection. “On average, it takes almost two and a half years to resolve an asylum claim,” Jonathan Blitzer reported in The New Yorker. The Biden administration, NPR, reported, is considering a plan—devised with heavy input from the Migration Policy Institute—that would seek to speed the process by empowering asylum officers from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to decide more cases of people apprehended at the border. They already do this with asylum seekers who apply elsewhere in the United States. (We discuss this in an April 1 WOLA Podcast with asylum expert Yael Shacher of Refugees International.)

Mexican Army kills Guatemalan citizen amid southern border crackdown

Mexico has responded to the Biden administration’s appeals to reduce migration flows by deploying more military, security, and migration personnel to its border with Guatemala. On March 27 a large number of soldiers, marines, national guardsmen, local police, and INM agents—3,000 people by one estimate—paraded through Tapachula, the largest city near Mexico’s southern border, then arrayed themselves along frequently used border crossings. On the Guatemalan side, in the border town of Tecún Umán, security forces increased their presence as well; officials from both sides held a protocolary photo-op in the middle of the border bridge over the Suchiate River.

Mexico’s Army is part of the deployment, making migration control one of many internal non-defense roles that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has encouraged the military to take on more fully. One army unit carrying out these duties, the 15th Motorized Cavalry Regiment, was involved in a tragic incident along the border on March 29.

Soldiers shot and killed a 31-year-old Guatemalan citizen, Elvin Mazariegos, a passenger in a truck near a usually unmonitored land border crossing in Mazapa de Madero, near Motozintla, Chiapas in the mountains north of Tapachula. When the truck, en route back into Guatemala, shifted into reverse upon seeing a group of Mexican Army soldiers, one fired at the vehicle in an incident that Mexico’s Defense Secretary called “an erroneous reaction.”

Like about 10 percent of residents of a zone where Mexico and Guatemala blur together and many road crossings lack customs or INM presence, Mazariegos, a resident of the Guatemalan town across the border, worked transporting products to and from retail stores on both sides. On March 29 he had gone with co-workers “to drop off money at bodegas where he worked.” Like most, he did not have an official border crossing card.

In areas like Mazapa de Madero, Mexico’s Animal Político notes, encounters with government forces often mean dealing with corruption. “An ‘assist’ to the authority in exchange for not having a rigorous inspection. According to his sister, the victim had already suffered on occasion from having to pay these bribes.”

That may explain why the vehicle in which Mazariegos was traveling appeared to seek to flee the scene. One of the combat-trained soldiers responded by firing several shots at the vehicle, despite the lack of any provocation or danger—a textbook example of why civil-military experts frequently warn about misusing armed forces for internal duties like migration control.

Hundreds of angry townspeople took the soldiers into custody—which sometimes occurs in Indigenous communities—and brought them to the Guatemalan side, where they stayed until the community received some assurances that the responsible soldier would be brought to justice and the family would receive some recompense.

Mexico’s Defense and Foreign Relations secretaries said the responsible soldier is “at the disposal” of the civilian criminal justice system. The Army told Mazariegos’s wife that it would pay the Guatemalan’s funeral expenses and reportedly offered a payout of 1 million Mexican pesos (US$50,000), which his family says is not enough to support the deceased man’s three young children.

Though not part of its ongoing southern border migration crackdown, Mexico was shaken this week by another official killing of a Central American migrant. Four police officers killed Victoria Esperanza Salazar, a Salvadoran mother of two daughters, who worked as a hotel chambermaid in the beach resort of Tulum. In a scene reminiscent of the May 2020 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a female police officer knelt on Salazar’s neck, breaking her spinal column and killing her, while onlookers recorded the incident and entreated the police to stop.

Salazar, 36, fled Sonsonate, El Salvador in 2016, and sought asylum in Mexico’s system, citing “gender violence.” Mexico’s refugee agency COMAR granted her asylum in 2017, and she had worked and raised her daughters in Tulum since then.

On March 27, a convenience store video showed Salazar appearing agitated, as though in the throes of a panic attack. After she left the store, police came and subdued her, inexplicably using extreme brutality and killing her. The attorney general of Quintana Roo, the state that incorporates Tulum, said that the four police officers are in custody and will be charged with “femicide.” President López Obrador lamented the crime: “She was brutally treated and murdered … It is an event that fills us with pain and shame.” In a stream of tweets about the incident, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele called on Mexico to hold the police officers accountable.

Articles this week in the Mexican publications SinEmbargo and Chiapas Paralelo provided updates on the miserable conditions faced by Central American and other migrants in the INM’s detention centers. In Chiapas and elsewhere near Mexico’s southern border, these detention centers are near capacity right now as migrant flows rise and the government’s crackdown intensifies.

Using partially available INM data, SinEmbargo counts the deaths of at least 20 migrants in INM detention in 2013 and between 2015 and 2019 (2014 and 2020 data are unavailable). Causes range from cardiac arrests and infections to “falling from bunk beds.” Brenda Ochoa of the Tapachula-based Fray Matías Human Rights Center (recipient of WOLA’s 2020 Human Rights Award) told the publication that migrants in INM detention receive “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, ranging from pressure to sign their deportation papers to physical and psychological abuse, particularly of women.”

Guatemala prepares possible caravan response

Amid word on social media that Hondurans were planning to form a northbound migrant caravan on March 30, representatives of the Guatemalan, Honduran, and U.S. governments held a virtual “high-level working meeting” to coordinate their response.

Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei declared a “state of prevention” for five of the country’s twenty-two departments, restricting freedom of movement, assembly, and public protest in order to ease the security forces’ efforts to block or disperse any migrants traveling in a caravan. While it is normally legal for residents of El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua to travel in each others’ territories without a passport, Giammattei based his order on COVID-19 precautions.

A statement from Amnesty International, the Mexico-based Institute for Women in Migration (IMUMI), and the El Salvador Independent Monitoring Group warned Guatemala “that imposing measures that could incite the excessive use of force against migrants and applicants for international protection is inexcusable.” The statement recalled Guatemala’s January 16 dispersal of an attempted Honduran caravan near the countries’ common border, in which “soldiers severely repressed people who tried to move forward.”

U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, the Biden administration’s point person for outreach to Mexico and Central America on migration issues, spoke by phone with President Giammattei on March 30. “They discussed the significant risks to those leaving their homes and making the dangerous journey to the United States, especially during a global pandemic,” along with priorities for economic assistance, according to a White House readout of the call. Even as the Guatemalan president decreed a state of emergency, the official record notes, Harris “thanked President Giammattei for his efforts to secure Guatemala’s southern border.”

In the end, by April 1 Guatemalan forces had quickly dispersed a small caravan whose members crossed the border.

As the Biden administration develops a U.S. assistance response to Central America, Dan Restrepo, the National Security Council’s Latin America director during Barack Obama’s first term, argued in The Hill that some forms of U.S. aid to the region—while not solving migration’s “root causes”—could show results more quickly than most might expect. These include “immediate disaster relief, cash-for-work programs, COVID-19 vaccines, alternatives to irregular migration, and a clear break with predatory elites.” On that latter point, Restrepo suggests publicly indicting Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was repeatedly named as a co-conspirator in narcotrafficking, in a U.S. trial that concluded this week with the president’s brother being sentenced to life in prison.

Speaking with NPR, Juan González, who holds Restrepo’s old position in Joe Biden’s NSC, repeated the phrase “predatory elite” to describe Central America’s corrupt political class. “You have, frankly, a predatory elite that benefits from the status quo, which is to not pay any taxes or invest in social programs,” González said. “Migration is essentially a social release valve for migrants.”

Links

- WOLA’s latest audio podcast discusses the border situation and how the asylum system should work, with guest Yael Schacher of Refugees International.

- Though the Biden administration’s 60-day pause in border wall-building has expired, it remains in place pending an eventual announcement of a plan. However, eminent domain cases in Texas courts have not been closed, and the government continues seeking to seize private property along the border for wall construction.

- NBC News, USA Today, and the Guardian covered Democratic and Republican legislators’ separate “dueling” border visits, to different parts of Texas, over the March 26-28 weekend.

- Reuters’ interviews with migrants and smugglers, and reviews of closed Facebook groups, indicate how “coyotes” are feeding migrants many false messages about the Biden administration’s policies toward migrants at the border.

- Felipe de la Hoz at the New Republic and Julia G. Young at Time make the point that the history of U.S. foreign policy in Central America is a key “root cause” underlying migration from the region.

- House Homeland Security Committee ranking member John Katko (R-New York) and border district Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas) introduced legislation creating a $1 billion contingency fund, from which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) could draw to attend to migrants at moments when they arrive at the border in large numbers.

- “Predicting a problem is not the same thing as having the right tools at your disposal,” writes Cecilia Muñoz, who headed the Domestic Policy Council in the Obama White House, in The Atlantic. Muñoz voices exasperation with “immigration advocates who project confidence that 100 percent of migrant families are fleeing danger and deserve asylum,” adding that “most are unable or unwilling to name any category of migrant who should ever be returned.”

- “The bottom line is that through expulsions and deportations, the United States is returning migrants and asylum seekers to situations of instability and danger amidst a pandemic, and this must be stopped,” reads an explainer document from the Latin America Working Group.

- “Immigrants are not coming to the U.S. because they are attracted by President Joe Biden’s inclusive language, and they were not repelled by former President Donald Trump’s use of racist imagery,” argues Greg Weeks of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. At Mother Jones, several immigration experts voice doubts about whether Biden administration messaging makes much difference for would-be migrants’ decision making.

- “One of the reasons why Mexican migration [to the U.S.] went down so much after 2007 is that there are about 260,000 people every year who come from Mexico to work legally in the U.S. and go back home,” Andrew Selee of the Migration Policy Institute tells Politico in a wide-ranging interview. “In 2019, the comparable number [for Central Americans] was 8,000; last year, it was about 5,500. There really is no line for a Central American to get into.”

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson