With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here. We will not publish updates on August 13 and 20, but look forward to resuming on August 27.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Preliminary data point to 210,000 migrant encounters in July

David Shahoulian, the Department for Homeland Security’s (DHS) assistant secretary for border and immigration policy, submitted an August 2 declaration as part of ongoing litigation (discussed below) regarding expulsions of asylum-seeking migrants. Shahoulian’s document offers a preview of official data about migration at the border in the month of July, which Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has not yet released.

Some highlights:

- CBP is likely to have encountered about 210,000 undocumented migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border in July.

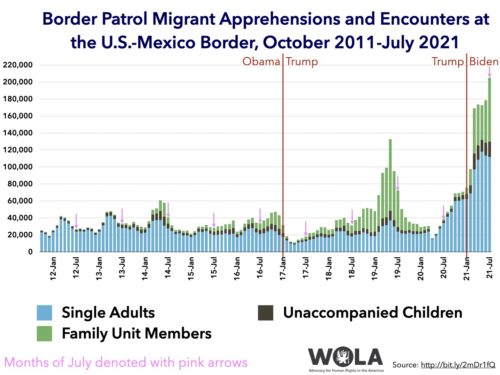

This would be the largest number of times that U.S. border authorities have encountered migrants since March 2000, when Border Patrol reported 220,063 apprehensions, and the third-largest on Border Patrol’s reporting of all monthly totals since 2000. This chart shows approximately how July would compare to all months since October 2011:

There is much double-counting, though: repeat crossings are far more common now than in 2000, since pandemic expulsions ease repeated attempts. As a result, the number of individual people whom CBP is encountering is probably in the low-to-mid 100,000s. That is still high, but probably not even in the top ten monthly totals of the past 22 years.

Still, it is extraordinarily unusual for a hot month of July to exceed migration levels measured in spring. Long-standing seasonal patterns no longer apply. As a new WOLA analysis points out, the number may keep increasing, as family and child migration patterns in place since 2014 have been heightened by the pandemic’s impact on governance and economies throughout the hemisphere. “Based on current trends,” Shahoulian’s document reads, “the Department expects that total encounters this fiscal year are likely to be the highest ever recorded.”

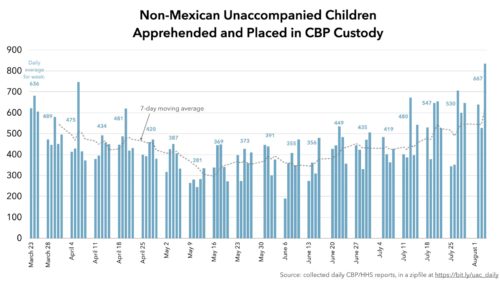

- “July also likely included a record number of unaccompanied child encounters, exceeding 19,000.”

Numbers of unaccompanied children arriving at the border had been inching upward since May, but jumped approximately after the July 4 holiday, for unclear reasons. On August 4, Border Patrol reported taking into custody a remarkable 834 non-Mexican children who arrived at the border unaccompanied. That is the largest single-day number in all daily reports on unaccompanied children that CBP and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have produced since March 24, and may be the largest daily number ever.

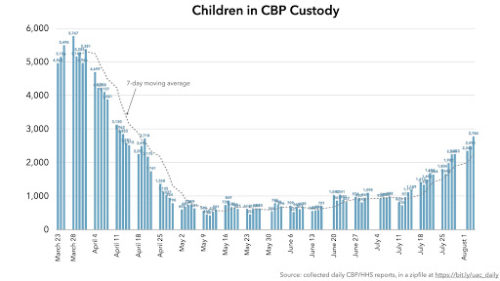

Along with the increase in child arrivals has come an increase, once again, in the number of unaccompanied children in Border Patrol custody, in the agency’s jail-like holding cells and processing facilities. A smoother process of handoffs to HHS, which runs a network of shelters as it works to place children with U.S.-based relatives or sponsors, had reduced numbers in Border Patrol custody from more than 5,000 in March to fewer than 1,000 in May and most of June. The volume of new arrivals, though, has caused the number to climb again.

As of August 4, 2,784 children were in Border Patrol facilities. Reuters reported on August 3 that, according to an unnamed “source familiar with the matter,” unaccompanied children were spending about 60 hours in Border Patrol custody, just under the legal limit of 72 hours for handoff to HHS. However, Reuters added that as of August 3, 877 kids had exceeded the 72-hour threshold.

- July encounters with family unit members are cited either as “over 75,000” or “around 80,000.”

This number of family members—which, like children, includes few repeat crossers—would be second only to May 2019, when Border Patrol apprehended 84,486.

- Two of the nine sectors into which Border Patrol divides the border “experienced a disproportionate amount of these encounters.”

They are both in Texas: the Rio Grande Valley, the easternmost part of the border; and Del Rio, in the central part of Texas’s border with Mexico, across from Coahuila, Mexico. “These two sectors have also experienced a disproportionate amount—about 71 percent—of family encounters.”

- As of August 1, Border Patrol facilities were at 389 percent of their “COVID-19 adjusted capacity,” with 17,778 non-citizens, including 2,233 unaccompanied children, in the agency’s custody.

10,002 of them were in the Rio Grande Valley sector, 3,623 of them in a temporary processing facility in Donna, Texas, which has a normal (non-COVID) operating capacity of 1,625. “Border Patrol was over capacity in seven of its nine southwest border sectors.”

Images posted on social media by Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas) and a Border Patrol union leader showed large numbers of migrants, including families with children, being held under bridges, outdoors, for days. These are Border Patrol’s Temporary Outdoor Processing Site (TOPS) under the Anzalduas International Bridge in Mission, Texas, and the Del Rio International International Bridge in Del Rio, Texas.

In the Rio Grande Valley, about 800 migrants, mostly asylum-seeking family members, are being brought each day to the Catholic Charities humanitarian respite center in downtown McAllen. “The center struggles every day to have enough supplies and donations to meet the growing demand,” reports Border Report, adding that the facility’s air conditioning broke down over the July 31-August 1 weekend “and temperatures were in the triple digits.”

Northbound migration becomes more visible in Colombia

Colombia sits along a route long used by migrants moving northbound from South America, often via countries like Ecuador or Brazil that are relatively more open to travelers from outside the continent. In its northwest corner, though, there is a major bottleneck: the Pan-American highway does not cross the Darién Gap, an area of dense jungle between the Colombian border and central Panama.

“Before the pandemic,” notes the Bogotá daily El Espectador, “Colombia issued a safe-conduct so that migrants could transit through national territory and leave within 30 days, but with the [pandemic border] closure, it stopped issuing them.” Although Colombia reopened its borders in May 2021, the safe-conduct system “has not resumed.”

Most international migrants transit Colombia with the aim of reaching the Atlantic coast town of Capurganá, which borders Panama. From there, they walk through the Darién Gap—a part of the journey to the United States that many migrants recall as the most miserable and dangerous—until they end up at facilities run by the Panamanian government and humanitarian groups on the other side. From there, they travel through Central America and either seek asylum in Mexico or seek to reach the U.S. border.

Capurganá is poorly served by roads, though, so migrants usually take a 40-mile ferry across the Gulf of Urabá, an inlet of the Caribbean Sea, from Necoclí. This municipality of 45,000 is part of Antioquia department, of which Medellín is the capital. A stronghold of pro-government paramilitary groups during the worst years of Colombia’s armed conflict 20 years ago, Necoclí remains under the influence of the Gulf Clan, an organized crime syndicate descended from the paramilitaries.

As migration surges throughout the Americas, the bottleneck in Necoclí has become dramatically backed up. About 10,000 migrants from Haiti and several other countries are in the beachfront town waiting for a chance to board one of the 12 daily ferries to Capurganá. The town’s only ferry company “simply cannot match demand,” Agence France Presse (AFP) reports; a translator for the company told CNN they “try to move eight or nine hundred migrants per day, but it’s hard.” This backup is forcing migrants to spend many days in Necoclí.

Colombian Defense Minister, visiting the town on July 31, said that the country’s navy would build an emergency pier that would allow more boats to operate. President Iván Duque pledged to work more closely with Panamanian authorities.

Most of the Haitian migrants stranded in Necoclí left Haiti years ago and settled in South America, often in Brazil or Chile. The pandemic dried up employment opportunities in these countries, though, and “they say their visas were not renewed,” reports AFP. Colombian migration authorities told CNN that Haitians are more likely to attempt the Darién route in family units with children.

The stay is expensive: a Haitian man told AFP that he “paid US$105 to enter Colombia illegally from Ecuador, another US$200 for a four-day bus ride to Necocli, and more still to pay police bribes,” and that a room in Necoclí costs US$10 per person. “Some migrants denounced mafias that sell them ‘tourist packages’ to make the journey from Ipiales, in Nariño [where the Pan-American Highway crosses from Ecuador to Colombia], charging up to 300 dollars to cross the border,” said Colombia’s human rights ombudsman, who visited Necoclí.

During the week, Colombia reported two apprehensions of migrant groups along the Pan-American Highway in the country’s southwest, several hundred miles south of Necoclí. Police stopped two buses carrying 99 Haitians in the Andean highlands of rural Nariño, and a vehicle carrying seven Haitians and a Brazilian in Valle del Cauca, not far from Cali.

12 developments last week affecting asylum seekers

As their numbers increase, the situation of asylum seekers in the United States and Mexico grew more complicated in several ways last week, though there was progress on some fronts. There is so much to report that this section avoids going into detail; follow links to learn more.

- U.S. District Judge Kathleen Cardone granted a temporary restraining order blocking a July 28 executive order from Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R). Abbot would have required Texas state police, in the name of preventing COVID spread, to stop, divert, and even impound vehicles transporting migrants—mainly asylum-seekers—released from CBP custody. The order would have crippled humanitarian groups’ efforts, and the Justice Department, which sued to challenge Abbott’s order on July 30, included statements from Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials contending that the order would block contractors hired to transport migrants. (In the Rio Grande Valley alone, Border Patrol has used contractors to transport most of 100,700 released migrants in Fiscal 2021, according to Sector Chief Brian Hastings’ filing.) Judge Cardone said Abbott’s order would end up “exacerbating the spread of COVID-19.” Her restraining order expires on August 13, when a new hearing is scheduled.In addition to the Justice Department action, the ACLU and several other Texas organizations filed suit against Abbott’s order on August 5. While the Justice Department is focused on the government’s ability to transport migrants, the organizations’ suit focuses on the racial profiling and other harms that might result from the order.Governor Abbott meanwhile continues to oversee a state effort to arrest, charge, and jail undocumented migrants on charges of trespassing near the border. According to Texas Tribune reporter Jolie McCullough, who has done the closest monitoring of this operation, more than 150 migrants are now jailed at a Texas prison in the town of Dilley, with the first arraignments scheduled for August 11. On July 30, McCullough witnessed Texas police separating a Venezuelan husband and wife, taking the husband off to jail as a “visibly confused” Border Patrol agent looked on.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a new order on August 2 renewing the controversial “Title 42” authority to quickly expel migrants, including asylum seekers, in the name of preventing COVID-19 spread. The order does not apply to unaccompanied children, but families will still be subject to expulsion, despite expectations a month ago that the Biden administration would no longer apply Title 42 to families.“Processing a family under Title 42 typically takes 10 to 15 minutes and is largely conducted outdoors, while processing a family for Title 8 can take 1.5 to 3 hours and is generally conducted indoors,” according to the above-cited filing by DHS’s Shahoulian. The document was part of the Biden administration’s defense to ACLU-led litigation against Title 42’s application to families. Negotiations between the ACLU and the government collapsed upon notice that the CDC would issue its renewal order, and both parties made a joint filing in Washington, DC district court on August 2.

- The renewal of Title 42, and of litigation, spells an end to two arrangements that were allowing a few hundred expelled asylum seekers per day judged “most vulnerable” to re-enter from Mexican border towns and be processed within the United States. The so-called Huisha-Huisha and Consortium processes were temporary arrangements that placed non-governmental organizations in the role of determining who was most vulnerable. They allowed over 16,000 individuals to be processed in the United States since May. Now, they are taking no new entrants.

- Mexico’s refugee agency COMAR revealed that, as of July 31, it had accepted 64,378 asylum applications so far in 2021. In August, less than two-thirds of the way into the year, the Mexican agency is likely to break its annual record for asylum applications of 70,405, set in 2019. While applicants come from 97 countries, 41 percent are Honduran, 21 percent are Haitian, and 10 percent are Cuban. For a week, COMAR closed its busiest office, in Mexico’s southern border zone town of Tapachula, Chiapas, for pandemic-related deep cleaning. When it reopened on August 5, hundreds of migrants gathered outside and local authorities deployed the National Guard when the crowd became unruly.

- The Rio Grande Valley Monitor reported, and the Washington Examiner added more detail, about Mexico (or at least, many Mexican states) possibly refusing expulsions of non-Mexican families whom CBP encounters at other parts of the U.S.-Mexico border. This step may already have been reversed by subsequent dialogues between U.S. and Mexican officials. But if it were to take place—which seems unlikely at the moment—it would put a halt to “lateral” expulsions, for instance where CBP takes a family into custody in a busy sector and transports them to a quieter sector for expulsion into Mexico. Neither the U.S. nor the Mexican federal government has confirmed the change.

- DHS announced on July 30 that it carried out its first “expedited removal” flight, returning family members to Central America who had either failed a credible fear screening or did not express fear of return to CBP personnel. The flight had a capacity of 147, but only 73 were family members because many had tested positive for COVID or been exposed to an infected person, the Washington Post found. As noted in last week’s update, the Biden administration announced that it would resume expedited removals on July 26.This process is flawed, a Houston Chronicle editorial contends: “Many migrants are unlikely to have lawyers to walk them through this process, subjecting them to Border Patrol agents who are often poorly trained for these encounters.” The Chronicle cites a 2016 finding from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom that “in 86.5 percent of the cases where a fear question was not asked, the record inaccurately indicated that it had been asked, and answered.”

- Reuters reported that DHS has begun expelling some Mexican and Central American adults and families by air, sending them deep within southern Mexico. It appears the first expulsion flight took place on August 5. “The United States will work with non-governmental organizations and shelters in southern Mexico to ensure that migrants can safely return to their home countries,” a source told Reuters—though there is no indication that such organizations or shelters are willing to cooperate with this arrangement. This process is for Title 42 expulsions into Mexico, not the expedited removals mentioned in the above point.

- NBC News reports that, in order to ease crowding of Border Patrol facilities, many unprocessed families will be transferred to ICE. That agency will either place families in alternatives-to-detention programs within the United States, or put them on deportation flights if they do not express credible fear of return. “In an unprecedented move,” NBC reports, “an agency usually tasked with detention, enforcement and removal of undocumented immigrants… will be performing health screenings, offering COVID vaccines, telling immigrants their legal rights and connecting them with non-governmental organizations that can help them.”

- The Washington Post reports that the Biden administration is preparing to offer the Johnson and Johnson single-dose COVID vaccine to migrants along the border. The vaccine would be administered to those being processed in the United States—including those facing deportation—but not to those expelled under Title 42. The same article notes that ICE continues to lag badly in its administration of vaccines within its network of U.S. detention centers, though an oversight official’s July 31 report claims that “46 percent of ICE detainees who were offered vaccine had refused it during the past month.”

- The average daily population of ICE’s detention facilities rose to 27,041 in July, up from 15,100 in January, the Biden administration’s first month. Of the 25,526 in ICE custody as of July 31, 3,318 (13 percent) were detained asylum seekers.

- As the Biden administration seeks to reunify the last few hundred of 3,913 asylum-seeking families separated during the Trump administration, a BuzzFeed investigation looked at what happened to some families after reunification. Documents indicate that “families from the first group of reunifications have reported homelessness shortly after entering the country.”

- A new report from the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) and FWD.us offers important perspective on asylum. It documents how the United States and other recipient governments have been steadily chipping away at the right to seek refuge for years. Policies weakening the ability to seek asylum “have caused unimaginable human suffering and loss, particularly for Black, Brown, and Indigenous asylum seekers,” the report points out.

Links

- A new WOLA commentary explains the current rise in migration at the border and throughout the hemisphere as part of a trend going back as far as 2014, heightened by the pandemic. It argues that the increase presents the Biden administration with an opportunity to show the world a different approach: how to handle a migration event without another cruel and ineffective crackdown.

- Local government in Mexico’s troubled border state of Tamaulipas announced on August 4 that the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) unit gave recognition awards—plaques citing “exceptional contributions” and “outstanding service”—to Arturo Rodríguez, head of a 150-person state police unit. Prosecutors accuse eight or twelve members of this unit, the GOPES (Special Operations Group), of carrying out a grisly massacre of 14 Guatemalan migrants and five other people near the border, in the municipality of Camargo, in January. VICE detailed the Camargo massacre and its investigation in a report also published August 4. Associated Press coverage of the DEA/HSI award describes other serious recent allegations that GOPES personnel have killed, stolen from, and otherwise abused civilians.

- CBP announced it will begin to outfit its officers and Border Patrol agents with body-worn cameras, in order “to better enhance its policing practices and reinforce trust and transparency,” especially regarding migrant encounters and use-of-force incidents. The agency plans to deploy about 6,000 body cameras by the end of 2021. Reuters notes that in 2015, CBP under the Obama administration had piloted the use of body cameras but ultimately rejected them, citing “a number of reasons not to adopt the devices, including cost and agent morale.”

- Mexico is building three permanent National Guard barracks in Ciudad Juárez, across from El Paso, including one in the western colonia of Anapra, a frequently used migration corridor.

- The government of Mexico, where legal firearms are rare, filed suit in a Boston federal court against several U.S. gun manufacturers and distributors. The suit alleges that these companies seek to profit from Mexican criminal groups, who pay for weapons smuggled south over the border from the United States, where they are easy to obtain legally.

- A report from the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP) recommends that the U.S. Department of Justice issue an “opinion that clarifies that climate change serves as grounds for refugee status under U.S. law.”

- A passenger van carrying 30 people, most of them probably undocumented migrants, crashed after taking a high-speed turn off a highway in Brooks County, Texas, about 80 miles north of McAllen and the border. The driver and nine passengers were pronounced dead. Brooks County is where large numbers of migrants die walking through arid scrubland trying to evade a Border Patrol highway checkpoint; its sheriff reported finding 50 human remains during the first 6 months of 2021.

- Mexican Army troops and national guardsmen in the border city of Mexicali rescued six men from the southern state of Guerrero, whom a criminal group was holding captive. It turned out they were being used as forced labor to build and operate an 80-meter-long, 16-meter-deep tunnel under the border into Calexico, California.

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson