With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

U.S. border reopens—but not to asylum seekers

On November 8, after nearly 20 months of closure to all “non-essential” foreign nationals, the United States opened its official land border crossings to documented, vaccinated travelers. Many ports of entry at first saw long lines as Mexicans with U.S. visas or border-crossing cards sought to reunite with relatives, resume doing business, or just shop on the U.S. side. Traffic flows quickly returned to normal nearly everywhere.

Ports of entry remain closed, though, to asylum seekers—migrants who lack U.S. visas but claim fear of return to their home countries—regardless of their vaccination status. The Biden administration continues to implement the Trump administration’s “Title 42” policy of expelling or quickly turning back all undocumented migrants, even if they seek protection.

In El Paso and Nogales, advocates accompanied asylum-seeking families, vaccination cards in hand, as they sought to cross into the United States to seek asylum the “proper” way—that is, by arriving at an official port of entry instead of climbing a fence or crossing a river. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers stationed at the borderline blocked them from accessing U.S. soil. The continued application of Title 42 even to vaccinated asylum seekers places great stress on administration officials’ insistence that the Trump-era measure is a public-health policy and not an immigration deterrent.

While CBP sought to dispel rumors that the border re-opening applied to undocumented travelers, anecdotal reports pointed to an increase in migrants arriving in Mexican border towns in the lead-up to November 8. “They haven’t listened to us and they don’t want to wait,” José García, whose Movimiento Juventud 2000 is one of several shelters currently filling up in Tijuana, told Reuters regarding recently arrived migrants who’ve received “misinformation.” About 1,200 people remain in a makeshift encampment just outside Tijuana’s main pedestrian port of entry into San Diego, California. Last week, municipal authorities built a fence around the encampment and cut off the power that residents had drawn from electric lines.

Many new asylum-seeking arrivals in Mexican border towns are Mexican citizens, primarily from states like Michoacán and Guerrero that are racked by criminal violence. Carlos Spector, a well-known El Paso-based immigration attorney who specializes in Mexican asylum cases, told the Border Chronicle that he expects to see a big increase in such cases after November 8. Some will be threatened Mexicans who already have U.S. travel documents: “that’s generally going to be the lower middle class on up. I’ve had calls from women working with coalitions searching for the disappeared.” And some will be Mexican human rights defenders who can no longer withstand constant threats to their lives and to their families’ lives: “The biggest thing I’m seeing is that these are heavyweight human rights leaders, who before told me they weren’t going anywhere.” Over roughly the last three years, nearly 100 human rights defenders have been killed in Mexico, including multiple family members of the disappeared.

This week saw several other notable developments in border and asylum policy:

- A report from Syracuse University’s TRAC Immigration project revealed that a larger proportion of asylum seekers won their cases in fiscal year 2021 than in fiscal year 2020. TRAC, which compiles large amounts of data obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, found that 37 percent of cases were successful in 2021 compared to 29 percent in 2020. Due to COVID-19 closing immigration courts for much of the year, however, 2021 saw only 23,827 asylum cases decided overall, compared with 60,079 decisions in 2020; only 8,349 people were granted asylum during this period, with another 402 granted some other form of relief. TRAC’s monthly plotting of the data shows that asylum approvals steadily increased after President Joe Biden was sworn in last January. “By September 2021, the asylum denial rate had dropped to 53 percent. That means that success rates had climbed to 47 percent.”

- The Biden administration’s court-ordered restart of the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” program, which forces non-Mexican asylum seekers to await their hearings inside Mexico, is proceeding apace, even as Mexico’s government has not yet assented to hosting those foreign nationals again. The Rio Grande Valley, Texas Monitor showed construction of tent courtrooms to hold teleconference hearings underway in Brownsville; they are also being built in Laredo. Two top House of Representatives appropriators, Barbara Lee (D-California) and Homeland Security Subcommittee Chairwoman Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-California), sent a strong letter to the Departments of State and Homeland Security (DHS) rejecting the program’s restart and laying out some strict conditions that a new Remain in Mexico would have to meet in order to receive funding from Congress. On November 15 (Monday), the Biden administration must submit to Texas District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk its latest monthly report documenting its “good faith efforts” to restart the program. (The last two reports are here and here.)

- Witness at the Border’s latest monthly report on U.S. deportation and expulsion flights finds that DHS ran 80 expulsion flights to Haiti between September 19 and November 7, “expelling an estimated 8,500 people, almost half of which were women and children.” October also saw 37 direct expulsion flights to Guatemala and 35 expulsion flights of Central American citizens to southern Mexico. Since the southern Mexico flights began in August, Witness at the Border estimates that the Biden administration has sent over 11,000 Central Americans to Tapachula and Villahermosa, Mexico.

- CBS News reported that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) will be sending court documents to about 78,000 asylum-seeking migrants who were released at the border without a court date, due to overloaded CBP processing capacity at the time. These individuals were issued “Notices to Report” at an ICE facility in their place of destination to begin their cases, rather than “Notices to Appear,” with specific hearing dates, which take longer to produce. While the majority of those who received “Notices to Report” indeed reported at ICE facilities, what the agency calls “Operation Horizon” is seeking to notify the rest by mail.

- The Associated Press covers immigration judges deciding asylum cases on the so-called “rocket docket”: the Biden administration’s effort to reduce the amount of time it takes to decide the claims of the most recently arrived migrants. Asylum cases routinely take three or four years or more to decide. By placing at the head of some courts’ lines the migrants who arrived at the border most recently, officials assume that the quick resulting decisions, usually within 300 days, might deter others with “weaker” asylum claims from attempting the journey to the United States. More than 16,000 cases are now on this “last in, first out” docket; critics worry that the policy weakens due process, as “it rushes the complex work of building asylum cases, making it nearly impossible for migrants to have a fair shot.”

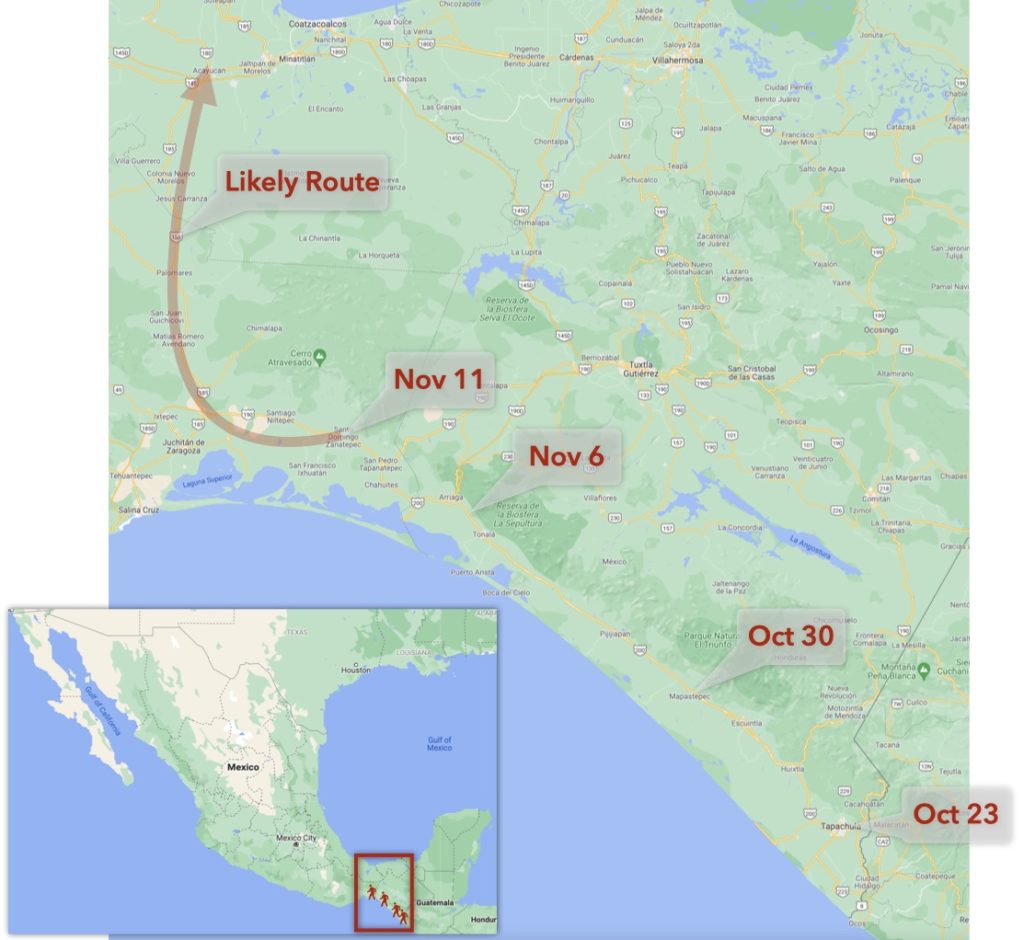

A diminished migrant caravan reaches the Isthmus of Tehuántepec

The migrant “caravan” that departed Mexico’s southern border-zone city of Tapachula on October 23 exited Mexico’s southernmost state, Chiapas, on November 7. By November 11, approximately 1,000 (or by one count, up to 2,500) mostly Central American migrants were beginning their day in the town of Zanatepec, in the state of Oaxaca, not far from Mexico’s narrowest point, the Isthmus of Tehuántepec. (The caravan’s past progress is covered in our last two weekly updates.)

The group is moving slowly, as Mexican forces—including the National Guard contingent closely accompanying the marchers—are preventing vehicles from transporting the migrants. Entirely on foot, they have covered about 200 miles in about 20 days.

The group is moving slowly, as Mexican forces—including the National Guard contingent closely accompanying the marchers—are preventing vehicles from transporting the migrants. Entirely on foot, they have covered about 200 miles in about 20 days.

Their numbers are dwindling. Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM) said that it now numbers fewer than 1,000 people, down from as many as 4,000 during its first days in Chiapas. It is hard to count them for sure, as not all are traveling in a tight formation: a group of 60, for instance, appears to be far ahead of the rest, already crossing from Oaxaca into the state of Veracruz.

Exhausted and frequently ill, many caravan participants, especially parents with children, have been turning themselves in to Mexican migration authorities. The INM announced on November 10 that it has delivered humanitarian visas to 800 “vulnerable” caravan participants—children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and their relatives—who will be allowed to await their asylum decisions in the southern and central Mexican states of Puebla, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Morelos, Hidalgo, and Guerrero.

The two activists accompanying or leading the caravan have indicated to the press that they no longer plan to walk to Mexico City. The original intention was to go to the capital and petition for better living conditions, particularly the right to live in states other than impoverished Chiapas, while Mexico’s overwhelmed refugee agency, COMAR, decides on their asylum applications.

Now, though, Irineo Mujica and Luis García Villagrán say that the group intends to go straight to Mexico’s northern border with the United States. They blame Mexican forces’ aggression for the route change. In an October 31 incident that earned criticism from Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, National Guardsmen fired on a truck driving through a roadblock, killing a Cuban migrant and wounding several others. On November 4, though, a group of migrants confronted National Guardsmen with stones and sticks on the highway near the town of Pijijiapán, Chiapas. While no migrants were reported wounded in the incident, five guardsmen were wounded badly enough to go to the local hospital; all were discharged by November 6.

The caravan’s new route would avoid the capital, crossing the Isthmus of Tehuántepec on foot from Oaxaca into the Gulf of Mexico state of Veracruz. Caravan leaders say that they could be in the Gulf Coast city of Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz within 10 days. There, they might meet up with another caravan reportedly set to depart Tapachula on November 17 or 18, then head several hundred miles into the northern border state of Tamaulipas.

“It’s a painful road, when the migrants enter the corridor,” U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar told a press conference on November 9. “But the majority of them come to the corridor because they’ve been deceived by the traffickers, criminals and those organizations are the ones that are enriching themselves by millions of dollars.” In an apparent reference to Mujica and García Villagrán, the Ambassador blamed the caravan’s formation on people “doing it for the money, they’re not doing it for the benefit of the migrants… The organizers portray themselves as if they’re doing something for human rights, when in reality what they’re doing is filling their pockets with money that comes from the traffickers and criminals.”

The Ambassador provided no evidence to clarify this accusation, however. Those who participate in caravans usually do so in an effort to avoid having to pay a smuggler, seeking to get across Mexico instead through “safety in numbers.”

Indicators point to migration decline in October

According to preliminary CBP numbers reported in the Washington Post, migration at the US-Mexico border may have dropped by 25 percent in the three months between July and October. “About 160,000 border crossers were taken into CBP custody during the month, preliminary figures show, down from 192,000 in September,” the Post’s Nick Miroff reports. “It was the third consecutive month that border arrests have declined, after peaking at 213,593 in July.”

The sharpest decline, Miroff adds, is in arrivals of migrants from Haiti. CBP and its Border Patrol component apprehended about 1,000 Haitians in October, way down from 17,638 in September. That month, a sudden arrival of nearly 15,000 Haitian migrants in Del Rio, Texas, made national news.

The decline in Haitian migration owes to the uniqueness of the Del Rio event, a finite, one-time flow. (However, several thousand Haitians, most of whom lived in Brazil and Chile, remain in Tapachula, and along migration routes in South America, Panama’s treacherous Darién Gap, and Central America). It also owes to the Biden administration’s harsh response to that event: since September 19, DHS has expelled about 8,700 migrants back to Haiti on 82 flights. As a result, the number of Haitians seeking asylum in Mexico has increased: Haitians in October overtook Hondurans as the number-one nationality of migrants seeking asylum before Mexico’s refugee agency, COMAR, so far in 2021.

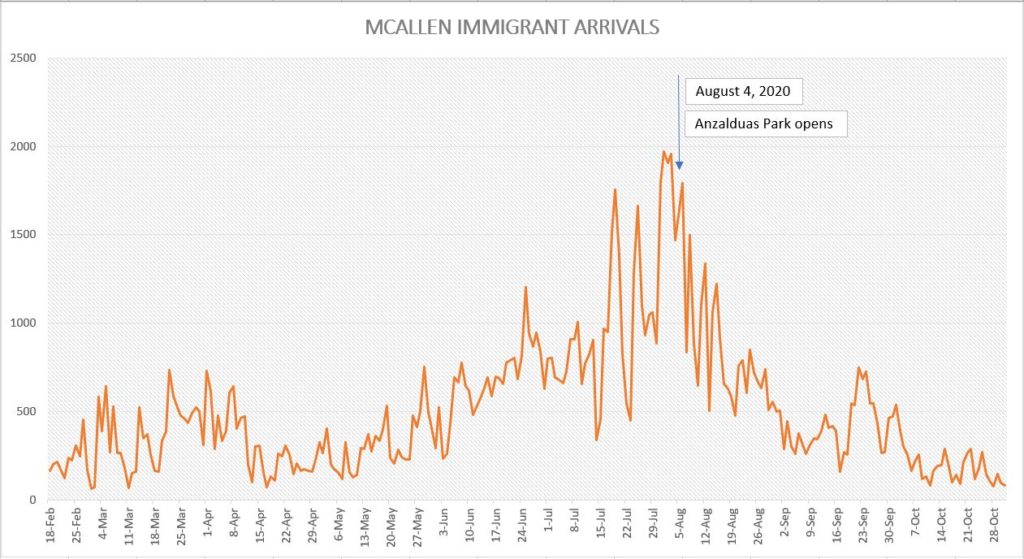

As we await CBP’s official release of October data, another indicator of a significant decline last month is a chart of immigrant arrivals in the very busy McAllen, Texas area, maintained by Valerie González of the Rio Grande Valley Monitor. Her chart, included in a larger article about how Border Patrol scrambled to deal with a sharp increase in child and family migration in July and August, appears to show McAllen’s migrant arrivals dropping to near their lowest levels since Joe Biden took office.

Arrivals of unaccompanied children, too, are down. While in July and August CBP was routinely apprehending more than 500 children per day, daily official reports of unaccompanied child apprehensions (collected here by Twitter user @juliekayswift) show the agency rarely encountering more than 400 per day anymore, and often fewer than 300. As of November 9, 12,418 unaccompanied children were in U.S. government custody (11,742 with the Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement, 676 in short-term CBP custody); that is still a very large number, but it is down from over 20,000 in April and May.

Links

- Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) began a crackdown on undocumented border-area migration this year, known as “Operation Lone Star,” that has led to the arrest of more than 1,500 people since July—including some asylum seekers—on state charges of trespassing, a misdemeanor. The Wall Street Journal revealed that only 3 percent of those 1,500 have been convicted so far. “Most of the rest are waiting weeks or months in jail for their cases to be processed.” Of 1,006 in jail as of November 1, 53 percent had spent more than 30 days confined—for a misdemeanor offense—due to small rural courts’ overwhelm. Meanwhile, “of 170 Operation Lone Star cases resolved as of Nov. 1, about 70% were dismissed, declined or otherwise dropped, in some instances for lack of evidence.” After release, many migrants are not expelled under Title 42: “some migrants who likely would have been deported had they been immediately caught by the Border Patrol are waiting in the U.S. after being released by state authorities.”

- “You’re preaching to the choir, and we appreciate you coming, and we appreciate you being here, and we’ll take your help,” the judge (top local authority) of Kinney County, Texas told leadership of the “Patriots for America.” This armed citizen militia group had arrived in the rural border county to respond to what it called “an invasion of this county” by migrants. Kinney County is one of the most active participants in Gov. Abbott’s “Operation Lone Star,” with over 1,000 arrests in two months. Concerns about this county-militia relationship are raised in a November 10 public information request by ACLU of Texas and the Texas Civil Rights Project.

- Reversing an initial statement that “it’s not going to happen,” President Biden said on November 6 that the Justice Department might settle lawsuits and pay significant sums to “compensate” many of over 5,600 migrant families who suffered harm when the Trump administration separated children and parents at the border. Dozens of Republican senators have sponsored an amendment to the 2022 defense authorization bill, currently under consideration, that would ban any such payments.

- Some non-citizens who served in the U.S. military but were later deported after committing criminal offenses are being allowed back into the United States after many years, under a new Biden administration policy.

- At least 45 Haitian migrants detained at the border are being denied access to counsel while held at Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Torrance County Detention Facility in New Mexico, according to several migrants’ rights groups. One pregnant woman was denied medical care at Torrance and had a miscarriage, according to a civil rights complaint that groups filed.

- Reporting from Haiti for Public Radio International, Monica Campbell talks to migrants who were expelled from the United States in recent months. Many are already planning to migrate again.

- Florida’s government reported spending $570,988 to deploy dozens of state law enforcement personnel and equipment to Texas’s border with Mexico, in response to a request from Gov. Abbott. “While in Texas, state law enforcement officers made contact with 9,171 undocumented immigrants,” the Miami Herald reported. “Just over 3% of those contacts resulted in a criminal arrest.”

- Nearly two months after being shown on widely shared video clips charging on horseback at Haitian migrants in Del Rio, Texas, at least six Border Patrol agents involved “were slated to sit down with DHS investigators to offer their own accounts of what happened in interviews on Tuesday and Wednesday,” CBS News reports.

- Manuel Orozco, a longtime Central America expert at Creative Associates, told an interviewer that he expects an increase in migration from Nicaragua after Daniel Ortega’s re-election in an illegitimate vote on November 7.

- “In historical perspective, the percent of criminal individuals apprehended by Border Patrol is low at about 1 percent in 2021,” writes Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute. “The rate of criminal individuals apprehended in 2021 is near the historical low point of zero to 1 percent during the late 1940s through the mid-1950s. Far from living during a period of high criminal apprehensions along the border, we are likely living during a period of relatively low border criminality.”

- The mayor of Laredo, Texas called on Mexican authorities to do more to police the highways leading up to his border city from Mexico’s interior. Laredo is the starting point for Interstate 35, a transcontinental U.S. highway that criminal groups use as a corridor for transshipment of illicit drugs to U.S. markets.

- The data visualization experts at the Pew Research Center shared a new post, “What’s Happening at the U.S.-Mexico Border in 7 Charts.”

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson