Credit: AP Images

Credit: AP Images

According to early media reports, by May 23 the Biden administration will have completed a phaseout of the “Title 42” pandemic border policy, and will once again recognize threatened migrants’ legal right to ask for asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

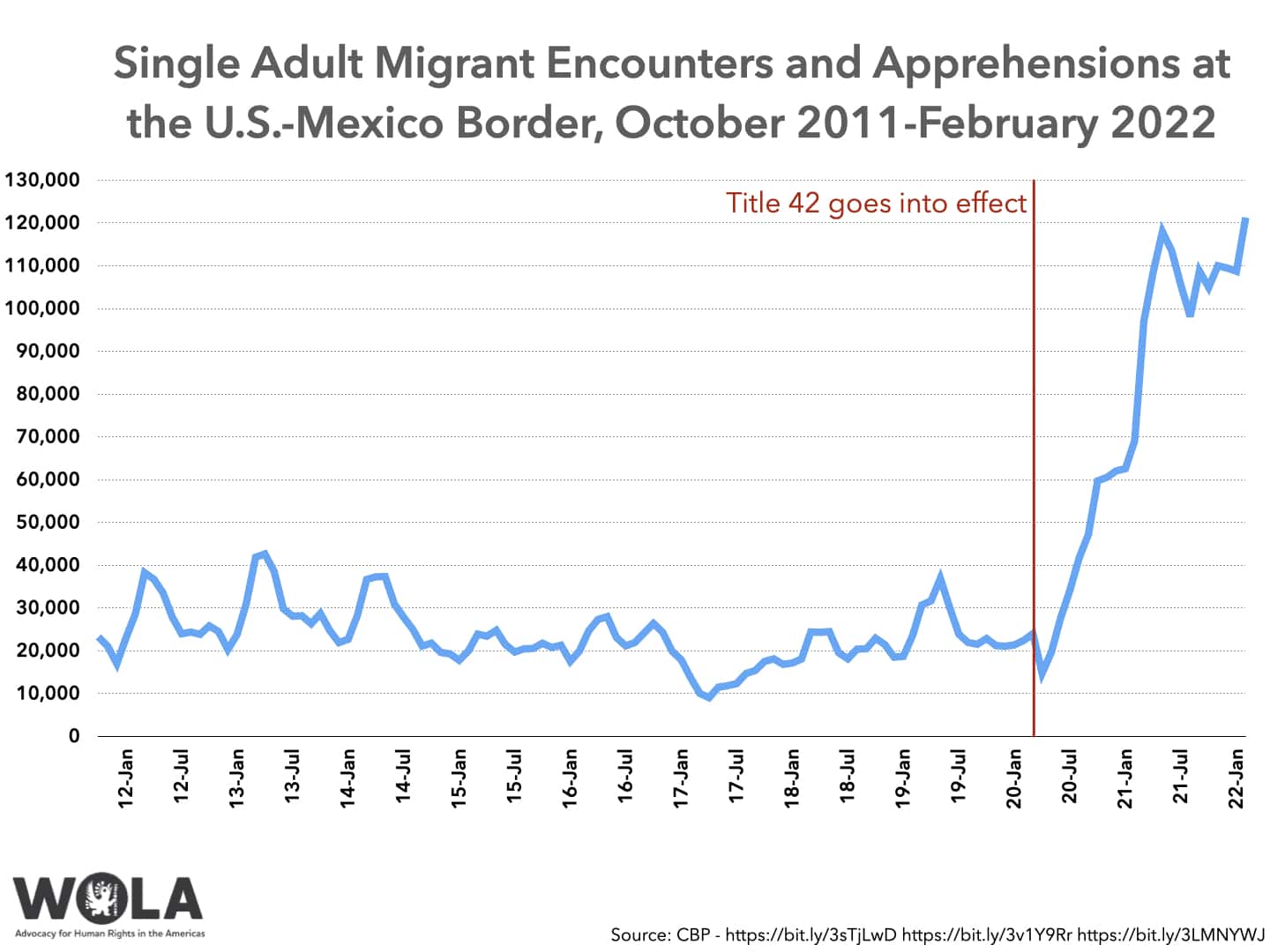

The imminent fall of the Title 42 barrier raises questions about the likelihood of a large increase in migration at the U.S.-Mexico border, and whether the Biden administration is prepared not only to handle it, but to address it in a more efficient and less cruel fashion than the U.S. government has managed asylum in past years.

WOLA offers answers to some of these questions.

Section 265 of Title 42, U.S. Code, a provision dating back to the 1940s, allows U.S. health authorities to deny entry of people or property into the United States “to prevent spread of communicable disease.” Section 265 is an imprecisely phrased 128 words long.

The Trump administration invoked it on March 20, 2020, in the early moments of the COVID-19 pandemic. It interpreted Title 42 to mean that Customs and Border Protection (CBP) could expel undocumented migrants as quickly as possible, without even affording threatened migrants the right to ask for asylum, a right guaranteed by the Refugee Act of 1980 (Section 1158 of Title 8, U.S. Code). In March 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officials did not believe that denying the right to seek asylum was warranted, but they went along with it under direct pressure from then-vice president Mike Pence.

Mexico agreed to accept land-border expulsions of its own citizens, and of Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran citizens. Most of these land-border expulsions took place within a matter of hours. Migrants from many other countries have been expelled by air, most notably to Haiti.

The Biden administration continued Title 42, though refusing to expel unaccompanied children. “The use of Title 42 is not a source of pleasure, but rather frankly, a source of pain,” Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said on April 30, 2021. Nonetheless, as of February 28, 2022, DHS had expelled migrants encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border 1,706,076 times. At least 1.2 million of those expulsions happened since Joe Biden’s inauguration.

60 percent of all migrants encountered at the border since March 2020 have been expelled under Title 42. That includes 78 percent of all single adults, 28 percent of family unit members, and 7 percent of unaccompanied children.

As it blocks access to the right to asylum, and expels many migrants to dangerous Mexican border towns, Title 42 has come under heavy condemnation from U.S. and international human rights organizations, migrant rights organizations, and the UN Refugee Agency.

Partial data collection efforts have found migrants expelled into Mexico suffering frequent assaults, robberies, rapes, and ransom kidnappings. Human Rights First, working with local organizations, has managed to document 9,886 cases of violent abuse in Mexico’s border cities just since January 2021. During March 2022 visits to Mexican border cities bordering Texas, humanitarian workers told WOLA that organized crime groups’ members wait every day near border bridges, watching for expelled migrants to abduct.

U.S. law states that asylum seekers should be able to express fear of returning to their countries at ports of entry—the official border crossings. But Title 42 closed the land ports of entry to asylum seekers for more than two years. This forced the most desperate to cross “irregularly,” climbing the border wall or fording the Rio Grande, braving desert heat, and preyed upon by organized crime. Others have ended up in wretched encampments, in Reynosa and until recently in Tijuana, waiting for a policy change to allow them to approach the border crossings.

As of March 30, the Associated Press was reporting, and other news outlets were confirming, that the Biden administration expects to end Title 42 restrictions by May 23. As of that date, undocumented migrants seeking asylum may no longer be expelled.

As was routine before March 2020, CBP will process asylum seekers according to U.S. immigration law.

The Biden administration will probably require a growing number of asylum seekers to await their U.S. hearings inside Mexico, under the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) or “Remain in Mexico” program. This Trump-era program, which the Biden administration canceled but a Texas federal judge forced it to restart, sent nearly 900 adult migrants back to wait in Mexico border towns between December and February. Over 90 percent of asylum seekers enrolled in Remain in Mexico so far have come from Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Cuba.

Title 42’s lifting coincides with spring, which is usually the heaviest time of the year for migration at the border. Migration flows are quite high right now as the world struggles to recover from a pandemic-induced economic collapse as well as ongoing violence and political unrest. Already, Border Patrol leadership is talking about 200,000 likely migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border in March, which would make this one of the busiest months of the past 12.

It is probable that a lifting of Title 42 will bring a further increase in migration, at least for the first few months. Large numbers of migrants, among them many asylum seekers, have been “bottled up” by knowledge that U.S. border policies would have expelled them to dangerous Mexican border cities. For instance, in early March WOLA interviewed a humanitarian worker in the border state of Tamaulipas, Mexico who estimated that about 20,000 migrants were waiting in the relatively safer city of Monterrey, a few hours’ drive to the south, for a chance to seek asylum in Texas. Migrants may also be drawn by smugglers’ often inaccurate messaging: their sales pitches will likely include deceptive portrayals of Title 42’s lifting as an opening of the border.

DHS officials told reporters on March 29 that they are expecting a large increase in migration, with scenarios ranging to as much as 12,000 or even 18,000 migrants per day at the border. (That seems dubious: 18,000 per day is 540,000 per month, which would more than double the 220,000 migrants apprehended in March 2000, the largest monthly number Border Patrol has reported.) Currently, during this unusually heavy month, a bit fewer than 7,000 migrants per day are being encountered, and the majority are expelled.

One probable outcome may be more migrant families and fewer single adults. Most parents with children turn themselves in to U.S. authorities in order to seek protection; for those from Mexico or northern Central America, Title 42’s lifting will eliminate the very high current likelihood of being expelled. As a result, more asylum-seeking families are likely to arrive at the border.

The opposite may happen with single adults, whose numbers have reached levels not seen since the 2000s. While many single adults seek asylum, a large number do not, and wish to avoid apprehension. For that population, Title 42 was only a minor hardship: a quick expulsion to Mexico for many meant an opportunity to attempt to cross again. In February, 30 percent of all migrants CBP encountered had already been caught once before in the past 12 months—a giant jump from 14-19 percent in the years before Title 42. Without Title 42, single adults who get apprehended will be processed, held for a time in Border Patrol custody, and perhaps even prosecuted for improper entry. We can expect adults’ repeat crossings to plummet, along with CBP’s “single adult apprehensions” statistic.

Many asylum seekers are already being released into the United States. 98 percent of expelled migrants are from Mexico and the three Central American countries whose citizens Mexico accepts (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras). But 33 percent of migrants encountered in February were not from those four countries. Title 42 expulsions of migrants from Brazil, Colombia, Haiti, and other countries usually happen by air. In other cases, like Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Russia, or Ukraine, diplomatic situations have all but stopped expulsions from occurring. Aerial expulsions are expensive, and a majority of citizens of countries subject to them (a slim majority, in the case of Haitians) do not get expelled.

These migrants are already being processed under normal immigration law. Each month, tens of thousands are released into the United States with appointments to appear before asylum officers and immigration judges.

Releases in the U.S. interior, then, are already happening, as they have for decades. They will likely increase in the months after Title 42 is lifted, assuming that more families and children (whom the U.S. government does not hold in lengthy detention) come to the border. It is reasonable to expect more releases of citizens of countries currently subject to heavy expulsions: El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico.

Biden administration officials are no doubt concerned about images of chaos and overcrowded facilities at the border in the weeks or months after Title 42 is lifted. Democrats worry about the probability of undocumented migration becoming a big Republican issue in the November 2022 congressional election campaign.

Large numbers of migrants arriving at the border, including a significant number of migrants with credible protection claims, are unavoidable. What is avoidable are those images of chaos and overcrowding. The Biden administration had more than a year to build capacity to receive a large flow of protection-seeking migrants, but it has fallen far short of what is needed. Now, it has about seven weeks.

The first ingredient to put in place—and in the short term, the most important—is processing capacity. “Processing” means checking backgrounds and health records, beginning asylum paperwork, evaluating the credibility of fear claims, and other tasks that should take place within 72 hours. This in turn means having facilities with the space and manpower to process protection-seeking migrants in an orderly and humane fashion. That manpower need not be armed, uniformed Border Patrol agents: “processing coordinators” and other trained civilians can perform these often bureaucratic but necessary tasks.

CBP appears to be far from having enough processing capacity in place right now. Even after more than a year of consistently high migration numbers, the agency has permanent and temporary centers able to hold and process only about 5,200 migrants at a time, plus small holding cells at Border Patrol stations. If arrivals rise to 12,000-18,000 per day who need processing, as DHS worst-case scenarios foresee, that capacity will be overwhelmed, and chaos will ensue.

In order to avoid weeks of “crisis” and images of disorder at the border, the Biden administration has about seven weeks to build up a great deal of processing infrastructure, which may involve bringing in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other parts of government to provide tents, logistical support, and processing personnel.

DHS has taken some incipient steps, like setting up a “Southwest Border Coordination Center” and moving Volunteer Force workers and about 400 CBP personnel to key areas. A FEMA regional administrator was named just days ago, on March 18. Still, the Department appears to be far from meeting its post-Title 42 infrastructure needs. A new DHS Fact Sheet recognizes that its 2022 budget appropriation “would not be sufficient to fund the potential resource requirements associated with the current increase in migrant flows.” The Department may have to call on other agencies for urgent assistance.

Large numbers of protection-seeking migrants have been the norm at the border since 2014. Even a draconian policy like Title 42 only reduced their numbers by a modest amount. Yet the U.S. security and immigration presence at the border differs little from the pre-2014 apparatus designed to address a population of mostly single adult economic migrants. The Biden administration needs to rebuild the U.S. asylum system to adjust to this new reality.

Vastly increased processing capacity is the first step. Protection-seeking migrants should be able to approach a port of entry instead of climbing fences or fording rivers. The ports of entry may be small, but larger processing facilities nearby, staffed by non-law enforcement personnel, should be able to handle the load.

Once released into the U.S. interior, asylum seekers should be covered by alternatives-to-detention programs in which case workers keep them in the system, ensure they show up to their hearing dates, and link them with services. Years-long adjudication backlogs can be shrunk by adding asylum officers and judges, and by rebuilding and rethinking the creaky immigration court system. Though the speed they envision raises due-process concerns, the Biden administration’s new asylum rules point in the right general direction.

U.S. agencies should also ensure close coordination with Mexican authorities, given the expected high number of arrivals to already overwhelmed, dangerous, and under-serviced Mexican border cities. Alarm about increased arrivals at the border must not manifest as increased pressure on Mexican authorities to ramp up apprehensions of migrants, or to outsource U.S. protection responsibilities to our southern neighbor.

In the short term, though, the goal is to get through the lifting of Title 42 as smoothly and humanely as possible. That means getting processing capacity in place, receiving people at the ports of entry, and treating them with dignity, including those who do not qualify for protection.

The only images we should see after May 23 should be unremarkable videos of people waiting to be processed in clean, orderly settings. With the amount of time that the Biden administration has had to prepare for the foreseeable consequences of Title 42’s end, there is no excuse for chaos.