With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Due to staff travel, there will be no Border Updates for the next two weeks. We will resume publication on May 13.

Subscribe to the weekly border update Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

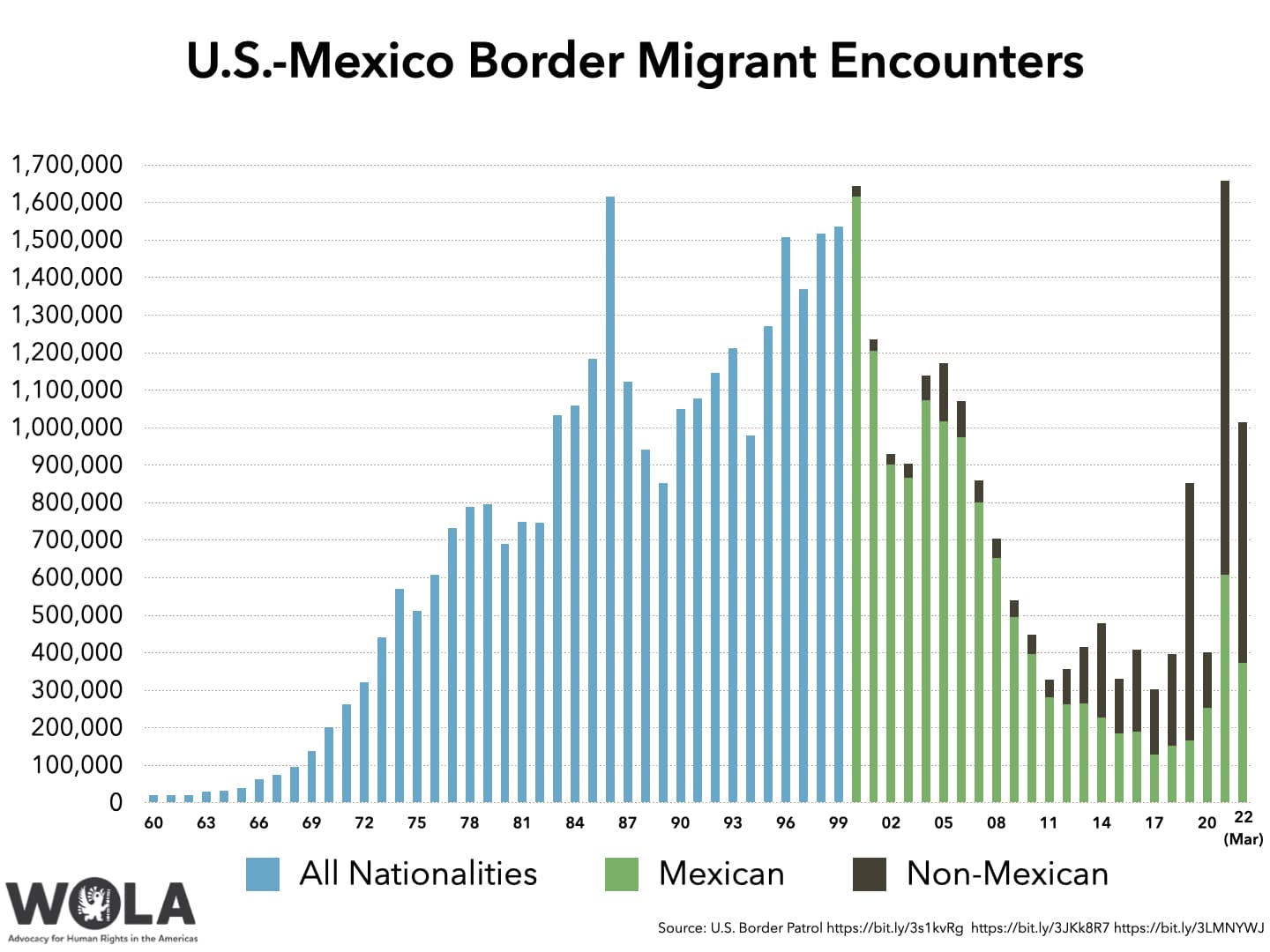

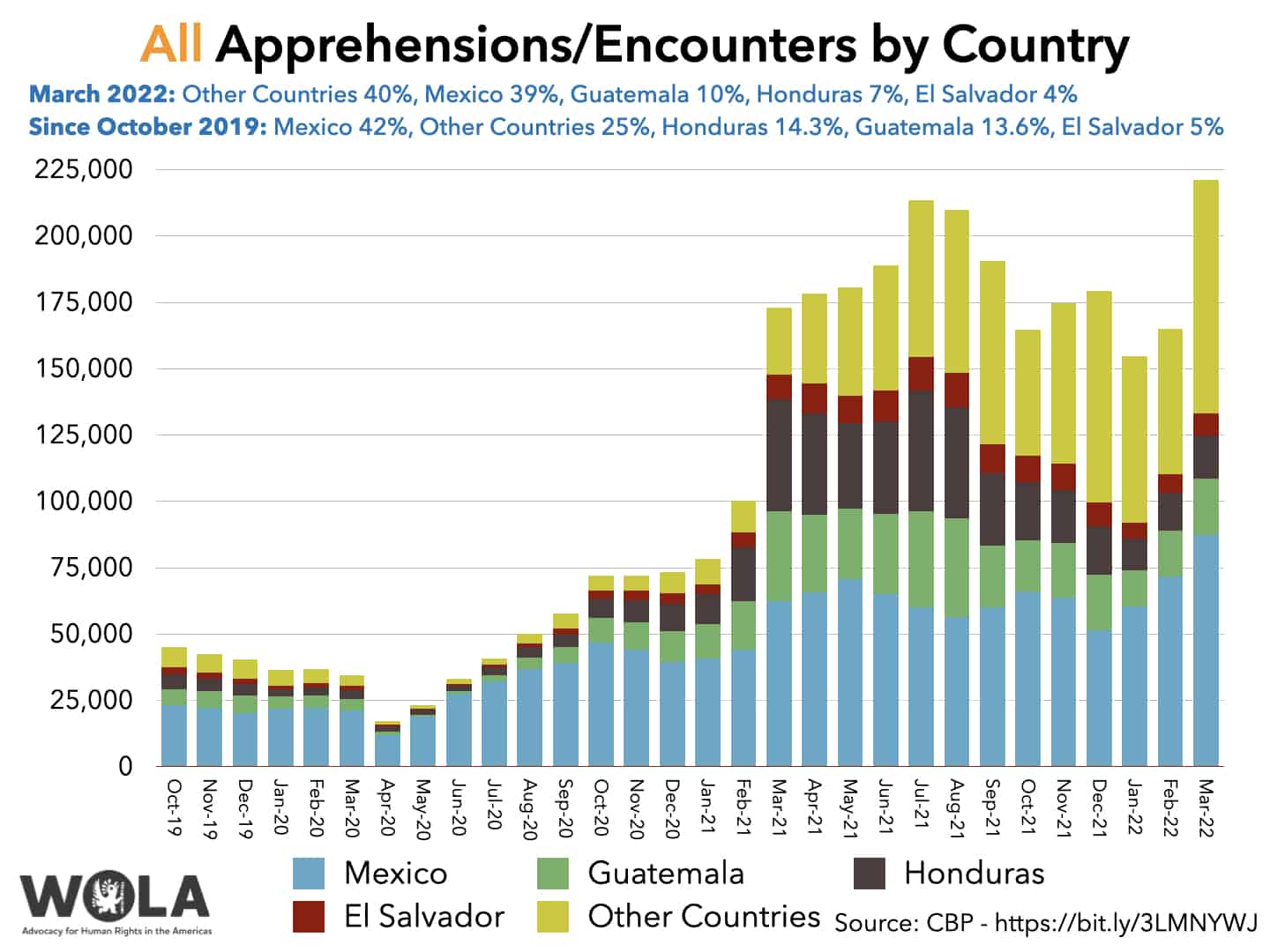

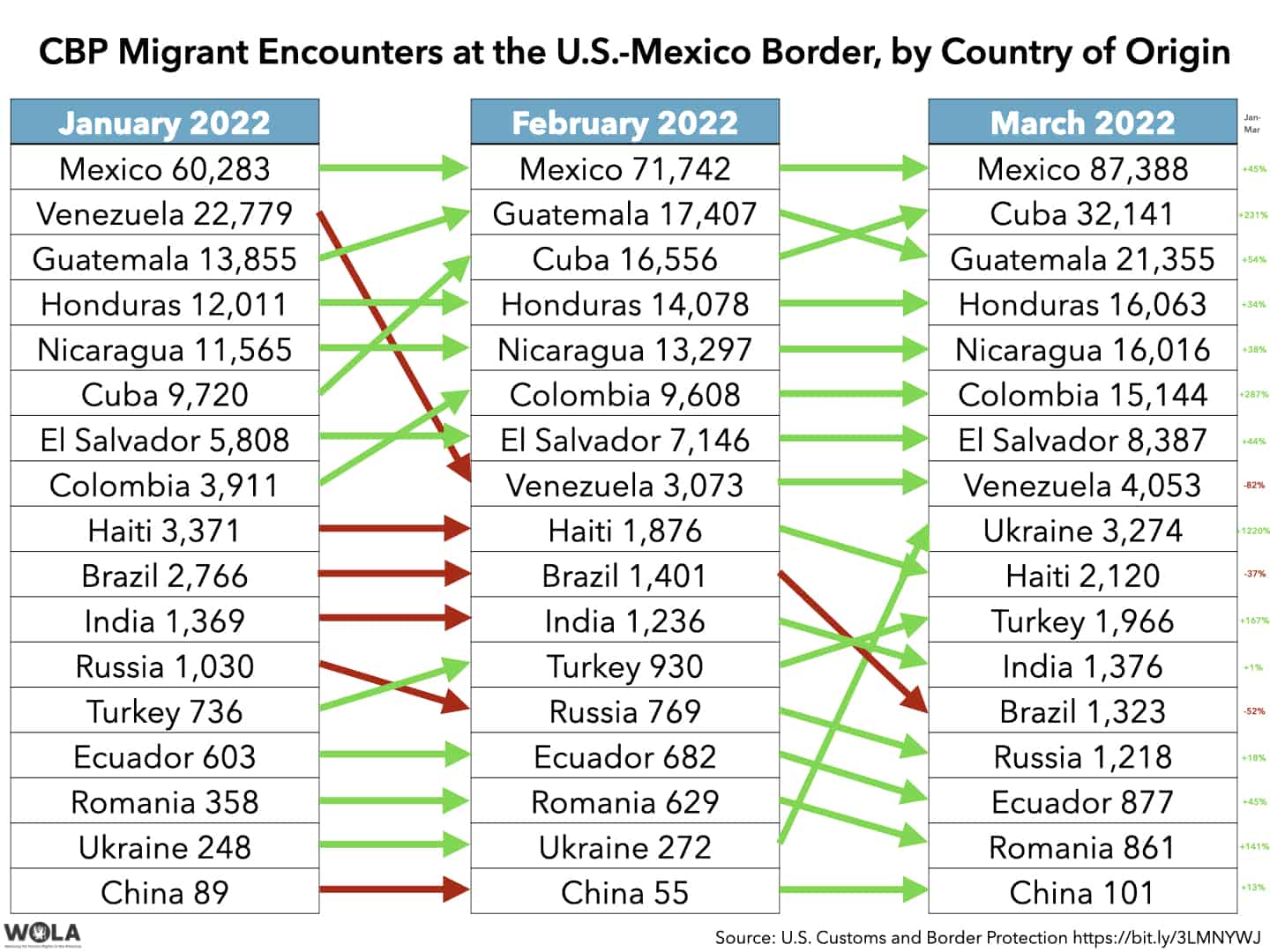

On April 18 U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) announced that it “encountered” undocumented migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border 221,303 times in March, 33 percent more than in February. The 209,906 times that Border Patrol encountered migrants between the official land ports of entry was the most the agency had recorded in any month since March 2000.

This pushed CBP’s “migrant encounters” total for fiscal year 2022, which began last October, over 1 million in 6 months. 63 percent of migrants so far this year have come from countries other than Mexico.

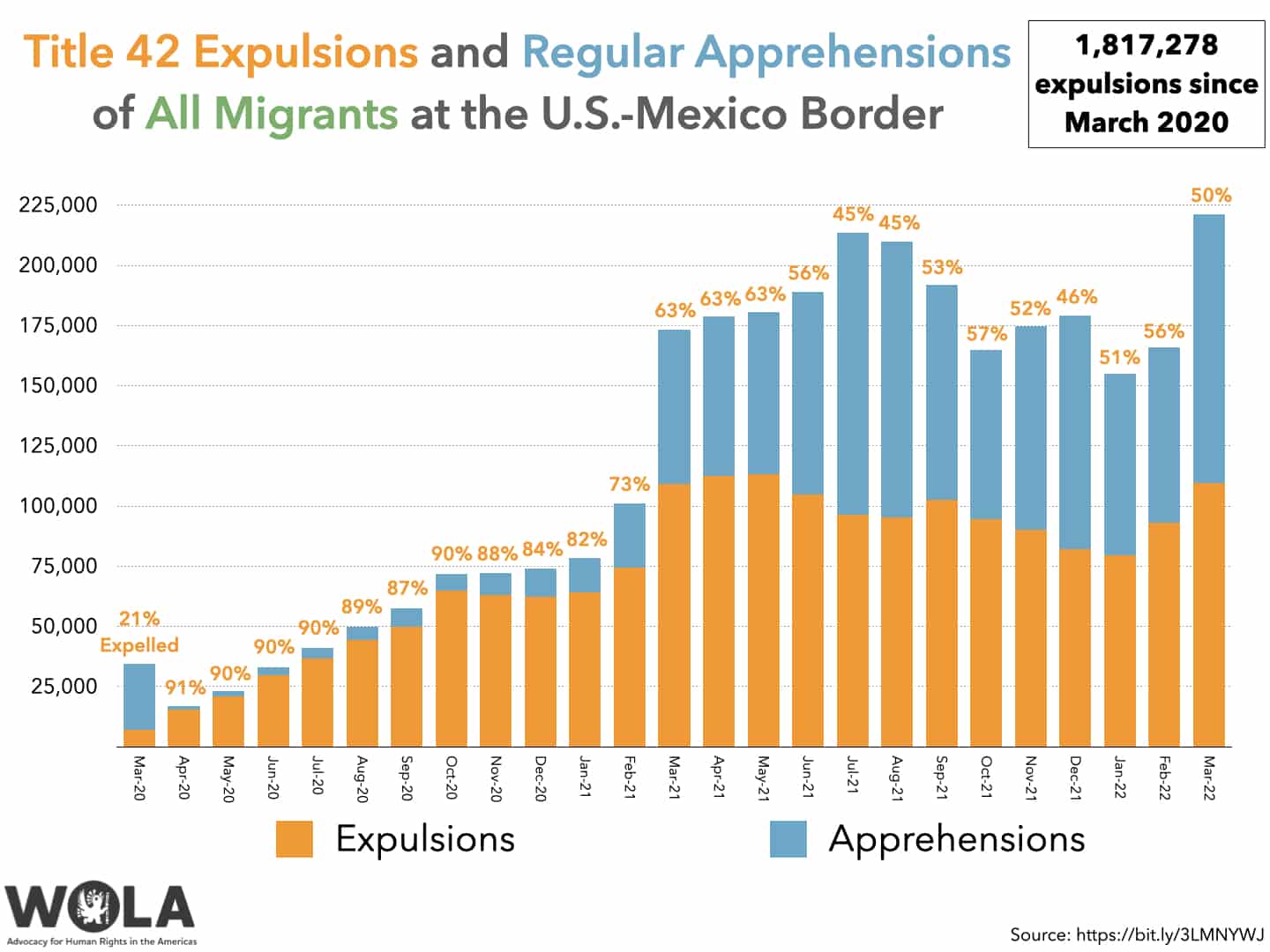

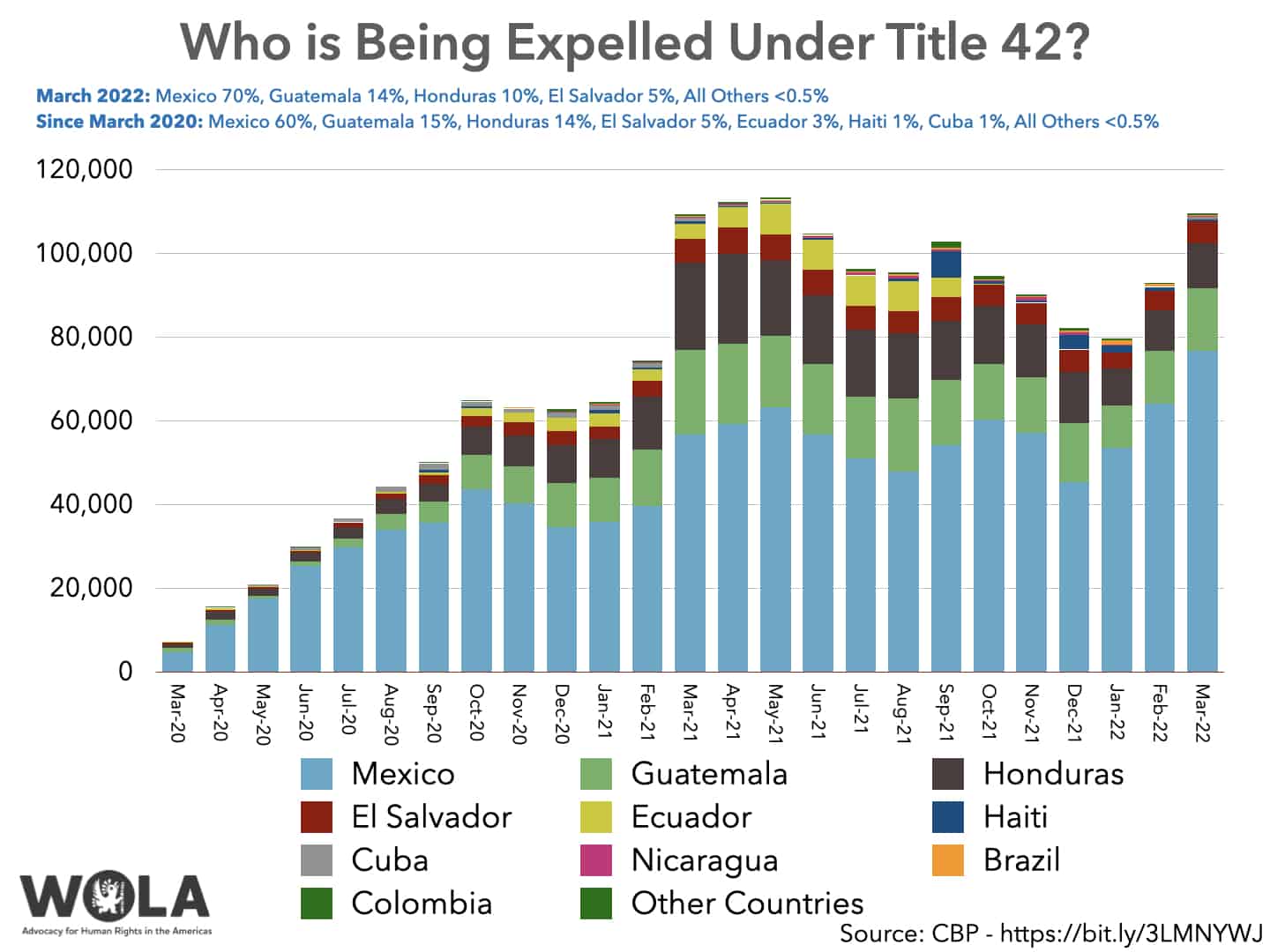

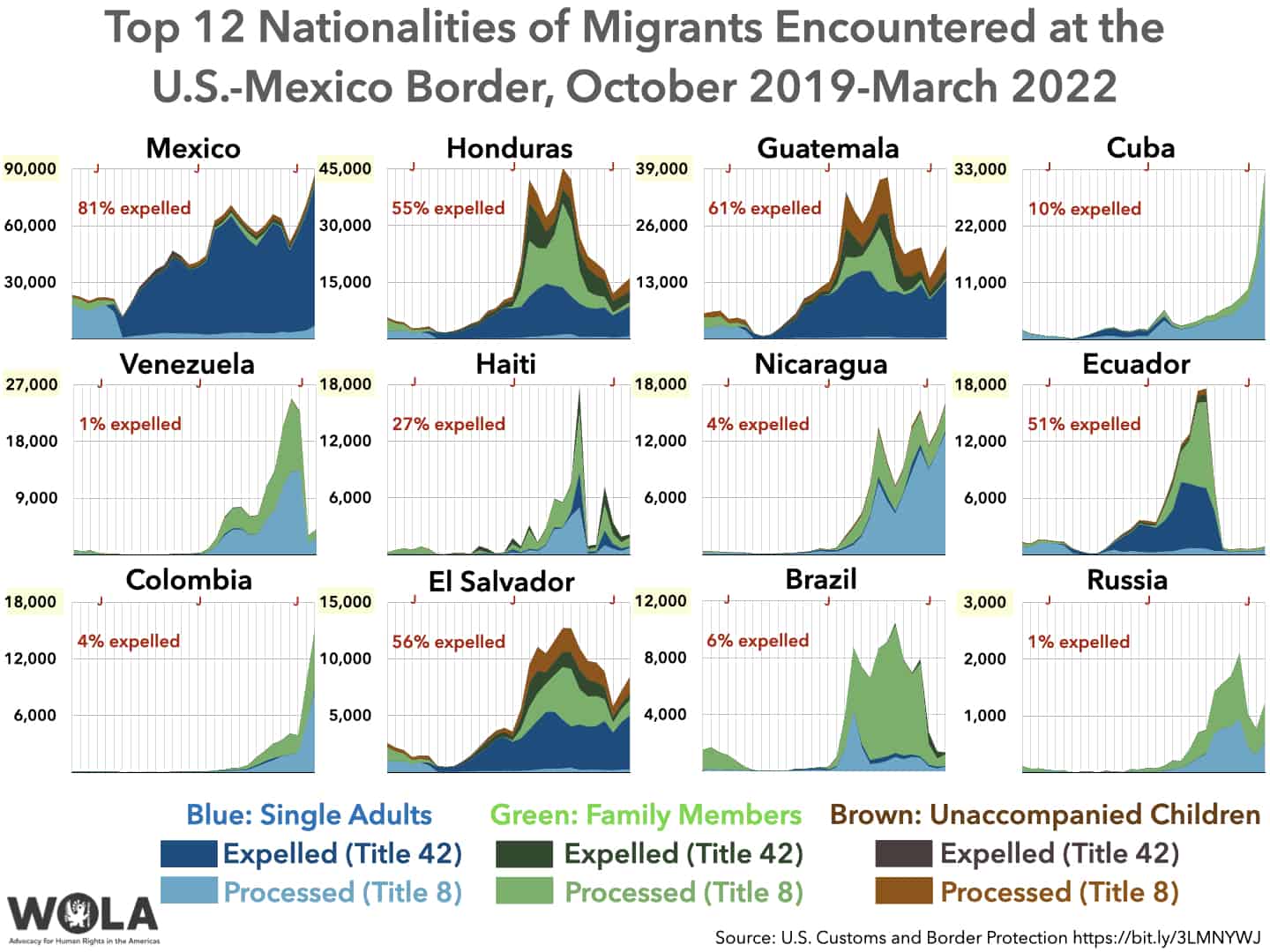

50 percent of March’s encounters ended with the migrant’s rapid expulsion, even if the migrant intended to ask U.S. authorities for asylum or other protection. The Trump and Biden administrations have used Title 42, the controversial pandemic authority allowing these expulsions, 1,817,278 times since COVID-19 first forced border closures.

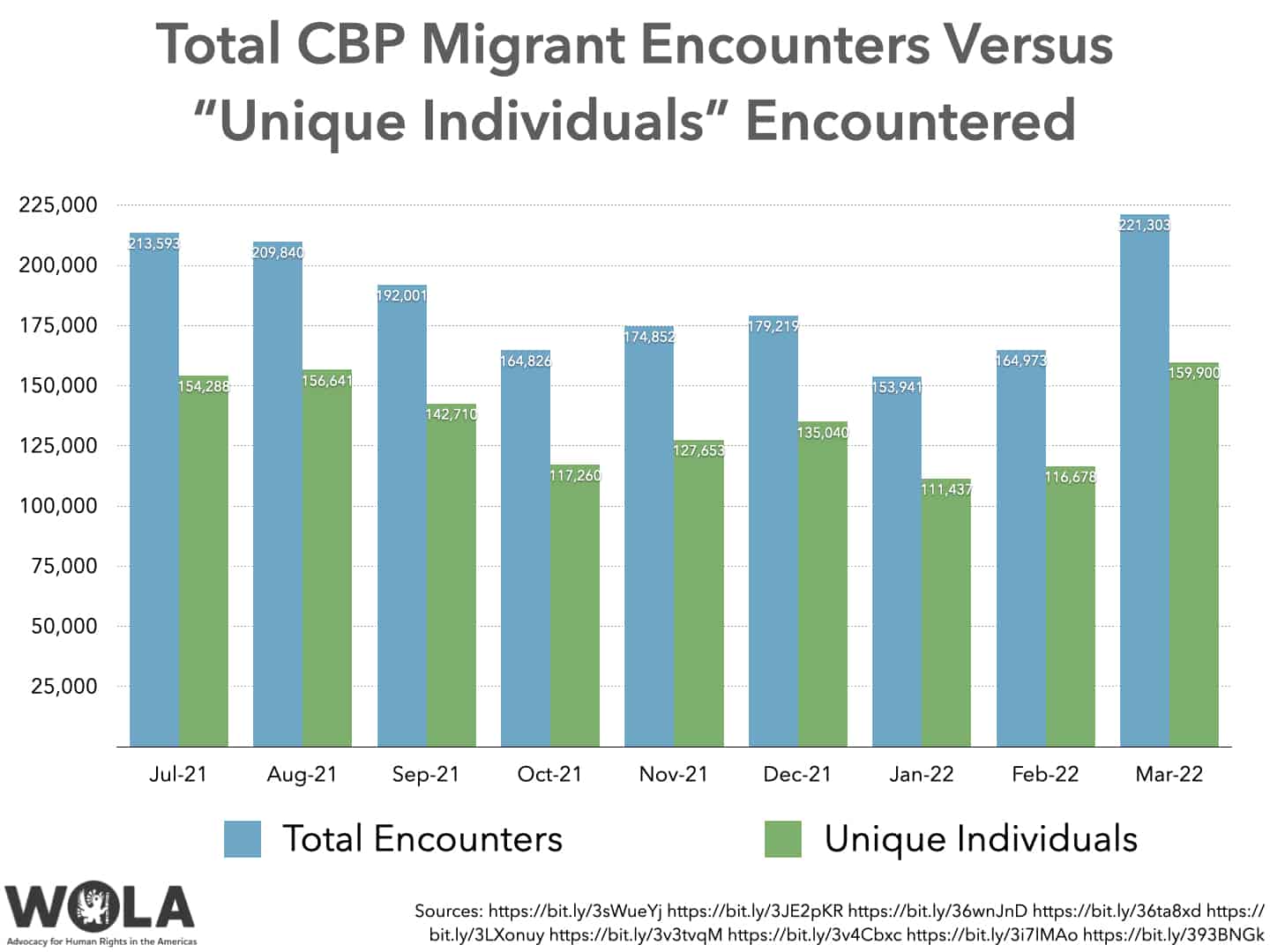

For migrants who want to avoid being apprehended, Title 42’s quick expulsions have eased repeat attempts to cross the border. In March, 28 percent of people CBP encountered had already been in the agency’s custody at least once in the past 12 months, double the 2014-2019 average (14 percent). That means the actual number of people encountered was significantly lower: 159,900.

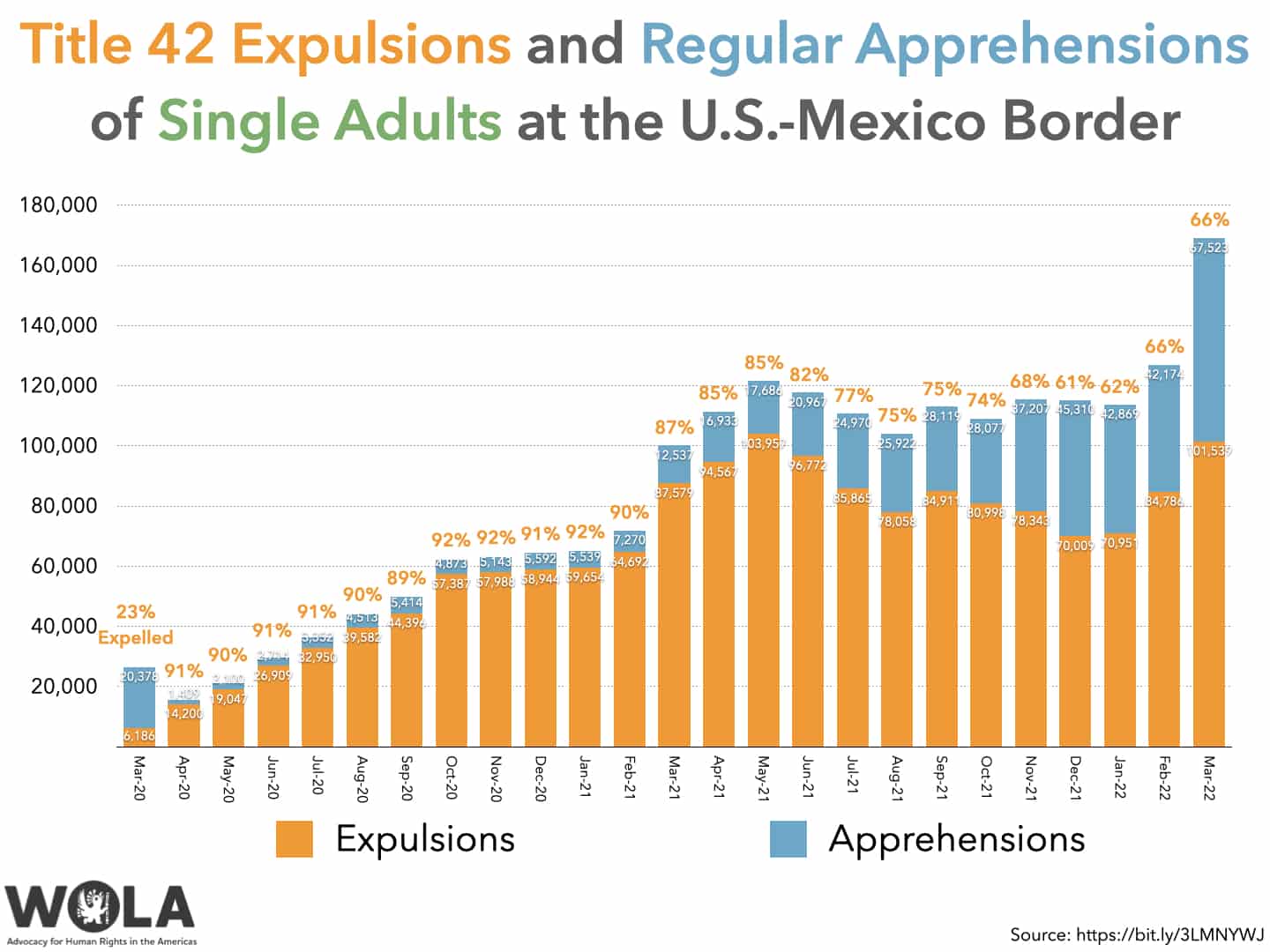

Though exceptions abound, single adults are more likely to attempt to avoid capture, while children and families are more likely to turn themselves in to seek asylum. The large number of repeat crossings contributed to the reporting of the most single adult migrant encounters—162,030—at least since October 2011, when the agency started providing public data about adult, child, and family migrants.

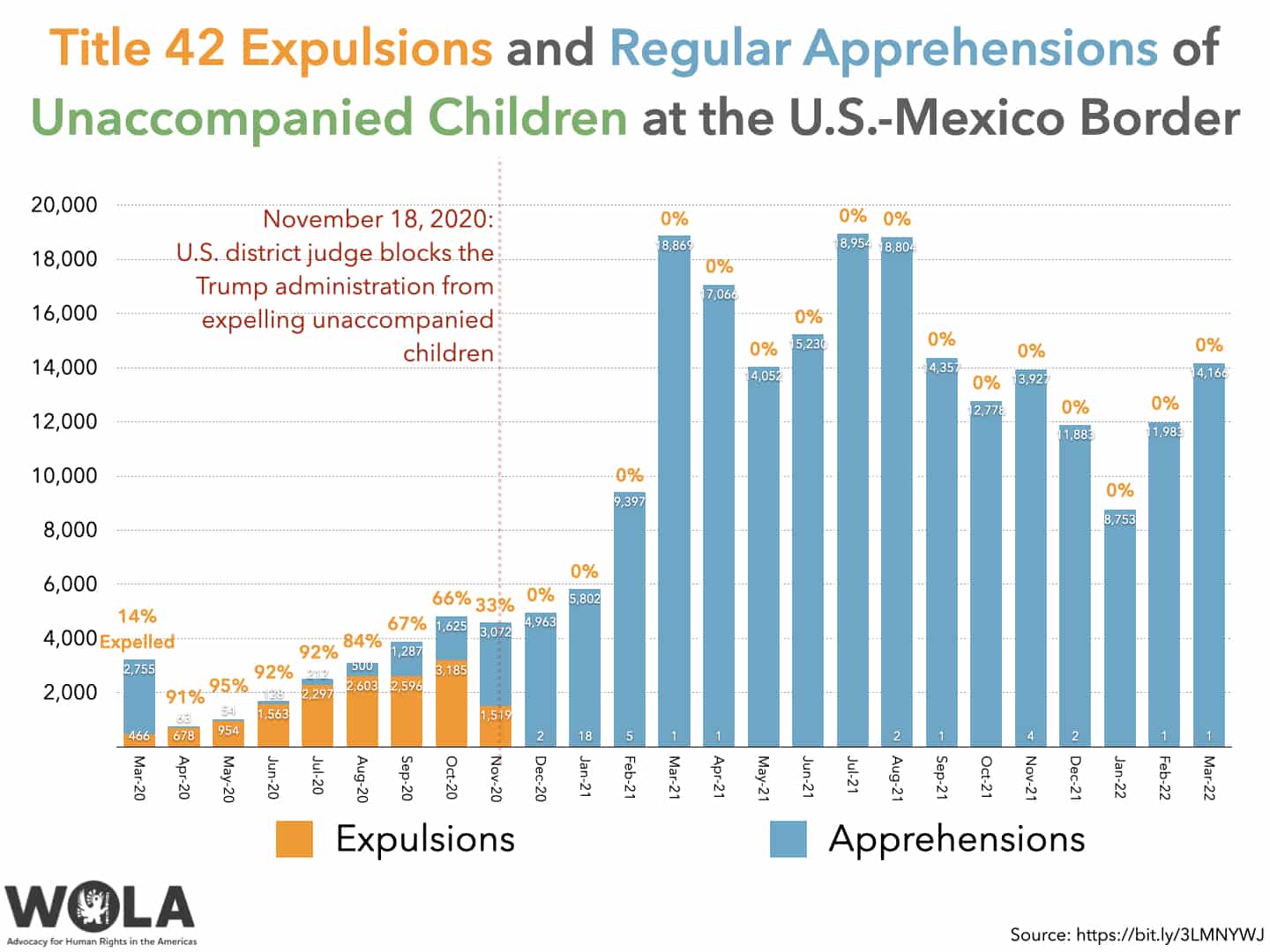

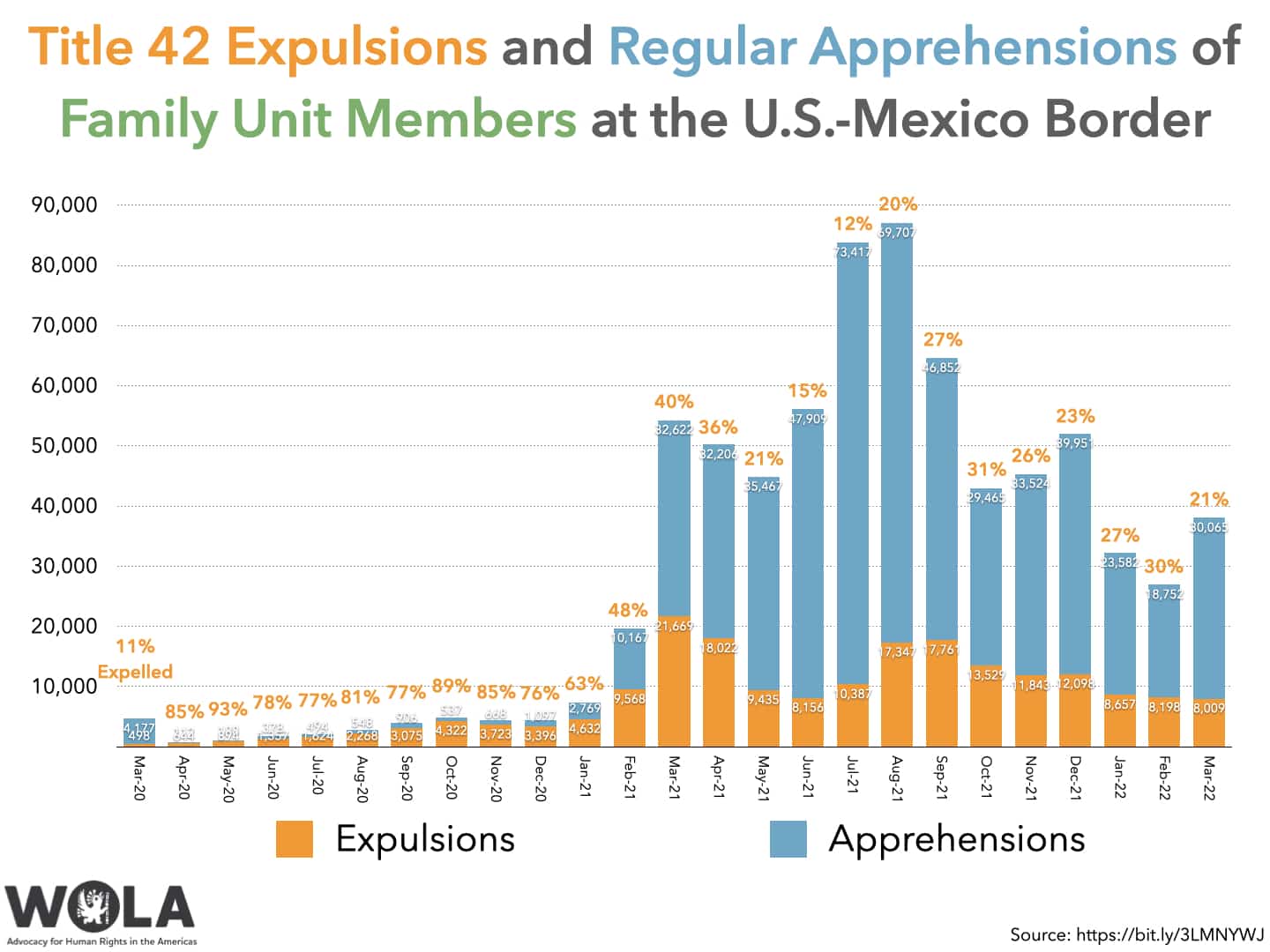

77 percent of migrants reported in March were adults, an unusually high proportion. Unaccompanied children (7 percent) and “family units” (parents with children, 16 percent) both increased from February to March, but were in fact fewer than in March 2021.

Until 2020 (when it was 88 percent), more than 90 percent of CBP’s migrant encounters were with citizens of four countries: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In March, those countries accounted for just 60 percent of migrant encounters. 88,110 were with migrants from somewhere else, which is certainly a record.

Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are the four countries whose citizens Mexico accepts as Title 42 expulsions across the land border. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must expel all other countries’ citizens by air, which is costly or, in some cases, diplomatically complicated. As a result, 99 percent of March’s 109,549 Title 42 expulsions were applied to citizens of these four countries only.

Of the other countries accounting for border arrivals, Cuba was in second place in March, with 32,141 of its citizens (about one in every 353 Cubans) encountered at the border last month. Cubans appear to be migrating in rapidly increasing numbers via Nicaragua, which lifted visa requirements for Cubans last November, enabling air travel. Cuban migrants’ numbers doubled from February to March, and tripled from January. Nearly all Cubans turn themselves in to U.S. authorities; if they remain in the United States for a year, the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 makes them eligible to apply for permanent residency.

Cuba has not accepted expulsion or other removal flights from the United States since February 2020, before the pandemic. The United States has meanwhile maintained almost no consular staff since the still-unresolved “Havana Syndrome” health incidents caused the U.S. government, in 2017, to reduce its diplomatic presence and close its consulate in Havana. On April 21, diplomats from the United States and Cuba met to discuss migration cooperation for the first time since July 2018, reviving what had been biannual talks.

Migrant encounters increased from February to March at the border for every nationality except Brazil, which declined slightly. In addition to Cuba (+231 percent), the countries whose citizens have seen the greatest increases are Romania (+141 percent), Turkey (+167 percent), Colombia (+287 percent), and Ukraine (+1,220 percent).

3,274 citizens of Ukraine, fleeing the Russian invasion that began on February 24, were encountered at the border in March, nearly all of them at ports of entry because the Biden administration encouraged CBP agents not to expel them under Title 42. Most have appeared at ports of entry between Tijuana and San Diego. As of April 21, the Washington Post reported, about 15,000 Ukrainian citizens had arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border. “Every day, 500 to 800 Ukrainians arrive in Tijuana,” the Wall Street Journal noted.

On April 21 the Biden administration announced a new program, calling it “Uniting for Ukraine,” allowing up to 100,000 Ukrainian refugees to receive two years of humanitarian parole in the United States, applying from outside the United States with help from U.S.-based sponsors. This will apparently mean a closure of the Mexico route which, because the U.S. government had lacked a process, was the simplest way for Ukrainians to reach the United States. Mexico’s Foreign Ministry warned Ukrainians against attempting to enter the United States through its territory after April 24, when CBP plans once again to employ Title 42 to prevent Ukrainian citizens from accessing border ports of entry.

The sharp increase in arrivals of citizens from Colombia appears to be a result of Colombian citizens flying to Mexico, which does not require them to have a valid visa, then traveling to the U.S. border—70 percent of the time, to Yuma, Arizona—to turn themselves in to authorities. While the United States accelerated Title 42 expulsion and ICE removal flights to Bogotá in March, CBP’s data show Title 42 being applied to 303 out of 15,144 apprehended Colombians last month.

The past year had seen similar sharp increases in migrants from countries from which Mexico did not require visas: Ecuador, Brazil, and Venezuela. When Mexico reinstated visa requirements—most recently for Venezuelans, on January 21, 2022—encounters with migrants from these countries dropped rapidly.

Despite likely entreaties from the Biden administration, Mexico may not be as quick to reinstate visa requirements for Colombians. Under the Pacific Alliance framework, which incorporates Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, member countries have a Schengen-style arrangement allowing visa-free travel.

The Biden administration officially remains firm in following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) decision, discussed in our April 1 update, to end the Title 42 expulsions policy by May 23. However, though the Biden administration has had more than a year to prepare for a likely post-Title-42 increase in migration at the U.S.-Mexico border, officials are privately voicing worry that DHS is not ready to process the increased number of arrivals in an orderly way.

Sources told Axios that “President Biden’s inner circle has been discussing delaying the repeal of Title 42 border restrictions.” A source “close to the White House” told CNN of a “high level of apprehension” in the West Wing, where staff “watch the border numbers every day.”

Axios reported that DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas “has privately told members of Congress he’s concerned with the Biden administration’s handling of its plans to lift Title 42 on May 23,” though Mayorkas’s public stance is that DHS will defer to the CDC. “Mayorkas has also indicated a level of frustration and unease with the repeal rollout.” A delay of the May 23 date is more likely than a full reversal of the decision to end Title 42, which “would effectively force the White House to overrule the CDC,” Axios adds.

Either way, there is some possibility that a Louisiana federal judge could strike down or suspend the CDC order before May 23. More than 20 states’ Republican attorneys-general have filed suit to block the end of Title 42, and the district judge hearing the case, Robert Summerhays, is a Trump appointee.

Some Democrats, worried about chaotic images from the border affecting their already grim midterm legislative election prospects, have been calling on the Biden administration to be more transparent about its plans for managing large numbers of protection-seeking migrants after Title 42 is lifted.

Mayorkas has resisted doing so publicly, telling CNN, “I think we have to be very mindful of the fact that we are addressing enemies, and those enemies are the cartels and the smugglers, and I will not provide our plans to them. We are going to proceed with our execution, carefully, methodically, in anticipating different scenarios.” Democratic legislators and staffers, Axios reports, say that “after Mayorkas walked them through the DHS’ preparations for the potential border surge, they did not feel the administration had reached the level of preparedness needed to carry out the operation successfully by May 23.”

Among the skeptics is Gary Peters (D-Michigan), the chairman of the Senate Homeland Security Committee, who said he would “still want to hear more.” While indicating he will defer judgment until he sees the full plan, Peters, according to The Hill, sees Title 42’s repeal as “something that should be revisited and perhaps delayed” until he sees what he regards to be “a well thought out plan.”

The Title 42 debate generated much political commentary over the past week:

Though it is one of many agenda topics, the high current levels of region-wide migration are likely to be the principal issue discussed when U.S., Canadian, and Latin American leaders convene for the Ninth Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles on June 6-10. This week, Secretary of State Antony Blinken led a U.S. delegation to Panama for a preparatory meeting with 21 foreign ministers from around the region. Blinken and DHS Secretary Mayorkas also held bilateral meetings with officials from Panama, which has seen record levels of migrants passing through its territory.

Blinken described a wide-ranging agenda:

Here in Panama, we talked about some of the most urgent aspects of this issue, including helping stabilize and strengthen communities that are hosting migrants and refugees; creating more legal pathways to reinforce safe, orderly, and humane migration; dealing with the root causes of irregular migration by growing economic opportunity, fighting corruption, increasing citizen security, combating the climate crisis, improving democratic governance that’s responsive to people’s needs.

Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols told reporters that the Summit of the Americas will likely produce a declaration on “migrant protection,” though it is not clear how detailed its commitments will be, the Miami Herald reported. Several U.S. and Latin American organizations, including WOLA, issued a statement calling on governments to develop their regional approach to migration “in consultation with civil society,” prioritizing “respect for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees through increased protection and complementary legal pathways, humanitarian assistance, and access to justice.”

The White House meanwhile issued a status report this week on its strategy to address the “root causes” of migration in Central America. Among efforts it notes are the encouragement of $1.2 billion in new private investment to create jobs, and the training of more than 5,000 Central America civilian police in calendar year 2021 “on topics such as community policing, investigations, and human rights.”

In Panama City, U.S. and Panamanian officials signed an arrangement to increase cooperation on migration, similar to one signed months ago with Costa Rica. It commits Washington to providing Panama with more resources to provide shelter to migrants arriving from South America, most of them headed toward the U.S. border.

Eastern Panama, near the Colombia border, is sparsely populated and roadless; the treacherous Darién Gap jungles used to be a natural barrier to migration. That is no longer the case: Panamanian migration authorities counted 133,726 migrants making the 60-mile walk through the Darién in 2021, up from a 2010-2019 average of 10,929 per year (and well under 1,000 at the beginning of the decade). Another 13,425 migrants exited the Darién Gap in the first 3 months of 2022. In 2021, a majority of these migrants were Haitian; so far in 2022, Venezuela is the most frequent country of citizenship.

Migrants often report passing through the barely governed Darién as the most harrowing part of their journey to the United States. Assaults, including sexual assaults, are frequent, and many speak of seeing dead bodies along the path.

Secretary Mayorkas paid a visit to the Darién region with Panama’s public security minister, Juan Pino. The Minister, EFE reported, said he explained Panama’s migrant processing procedures: they are “taken to migratory reception stations (ERM), where their biometric data is taken and they are provided with health care and food.” Pino added that “‘Panama is the only country that carries out verifications’ of migrants, which has produced ‘biometric alerts of terrorism and organized crime’” shared with DHS.

On April 15 the governor of Texas, Greg Abbott (R), lifted onerous cargo vehicle inspections imposed at the state’s border crossings, which had halted most trade between Texas and Mexico for several days. Abbott, a critic of the Biden administration’s border policies, had imposed the stoppage— covered in last week’s Border Update—in response to the imminent lifting of Title 42.

He did so after inking brief agreements with the governors of the four Mexican states that border Texas, who committed to increasing security efforts on their side of the border. Tamaulipas, for instance, agreed to carry out “special operations” along 10 migrant smuggling routes identified by U.S. authorities. Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, reacted strongly to Abbott’s tactics on April 18: “Legally they can do it, but it’s a very despicable way to act… I would say it’s chicanadas (half-baked) antics from the state government.”

Gov. Abbott’s blockade generated a backlash, as it caused financial losses for industries dependent on trade with Mexico. The Texas-based Perryman Group estimated $8.97 billion in losses to the U.S. economy between April 6 and 15, $4.23 billion of it hitting Texas’s gross state product.

Abbott also continued sporadic departures of half-filled buses of asylum-seeking migrants to Washington. These received little notice in the city’s busy downtown, while volunteers helped migrants arrange travel to their final east coast destinations. Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who represents El Paso and opposes Abbott’s policies, ironically thanked him in a tweet: “Bussing migrants to D.C. helps get them closer to their final destination and saves their sponsors travel costs. This is one of the most humanitarian policies [Abbott] has ever enacted. I’ll take the poetic justice while we wait for real justice.”

Abbott and other Republican governors remain determined to make border and migration issues a central theme for the 2022 campaign (congressional elections, plus Abbott’s bid for re-election to the Texas governorship). Analysts note that Abbott may have his eye on a 2024 presidential run, which would mean that the intended audience for his recent tactics is Republican primary voters nationwide. “This is all really about 2024. Abbott is worried about being outflanked by DeSantis,” Republican fundraiser Dan Eberhart, who backs Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), told the Washington Post. “Abbott needs to be focused on introducing himself to 2024 primary donors and staying relevant in the party nationally. Picking a fight on immigration keeps him on the news.”

Republican figures have been kicking around the idea of invoking the U.S. Constitution’s “invasion clause” to justify using law enforcement personnel and National Guard troops to block migrants, including asylum seekers. It remains far from clear that governors, rather than the federal government, would have the authority to determine whether migrants constitute an “invasion.” Abbott and Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R) also issued an April 19 press release announcing an “American Governors’ Border Strike Force,” along with 24 other Republican-led non-border states, that would contribute personnel to state border security efforts.

The largest state-government border security campaign has been Abbott’s “Operation Lone Star,” which has spent over $3 billion to build fencing, jail migrants on state trespassing charges, and deploy up to 10,000 National Guardsmen to the border. This operation continues to be troubled: