With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) released data on June 15 detailing its encounters with migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border the previous month. In May 2022, the agency took undocumented people into custody 239,416 times, a 2 percent increase over April. Since fiscal year 2022 started in October, CBP has apprehended migrants 1,536,899 times at the border. 2022 is certain to be a record year for migrant encounters, exceeding the 1,734,686 measured in 2021.

CBP’s Border Patrol component encountered migrants 222,656 times, the largest monthly total since the agency began reporting data by month in fiscal year 2000. The record for between ports of entry had been 220,063 apprehensions, measured in March 2020.

It is unclear, though, whether more “encounters” last month meant more “people” than 22 years ago. May’s 239,416 “encounters” were with 177,793 individual people; there is no record of how many individual people were encountered during the previous record-breaking month of March 2020. Still, 177,793 is the most since CBP started reporting individuals in its monthly releases last July, and 15 percent more than reported in April.

The Biden administration’s continued use of the Trump-era “ Title 42” pandemic policy—after its lifting was blocked by a federal judge last month—and which quickly expels many migrants with few consequences, has incentivized repeat crossings. Last month, 25 percent of migrants encountered had already been in CBP custody at least once in the past 12 months; in the six years before the pandemic, the percentage of repeat encounters had been much lower: 15 percent.

69 percent of May’s border encounters were with single adults, a greater share than was common in the years before the pandemic. (Though many single adults turn themselves in to seek asylum, they are less likely to do so than children and families; as a result, a greater share of repeat crossings inflates numbers of single-adult encounters.)

Single adult encounters declined by 2 percent from April to May, to 165,200. Encounters with members of family units (defined as parents with children) increased 8 percent, to 59,282, from April to May, and encounters with children arriving unaccompanied increased 21 percent, to 14,699. “In May, the average number of unaccompanied children in CBP custody was 692 per day, compared with an average of 479 per day in April,” CBP reported.

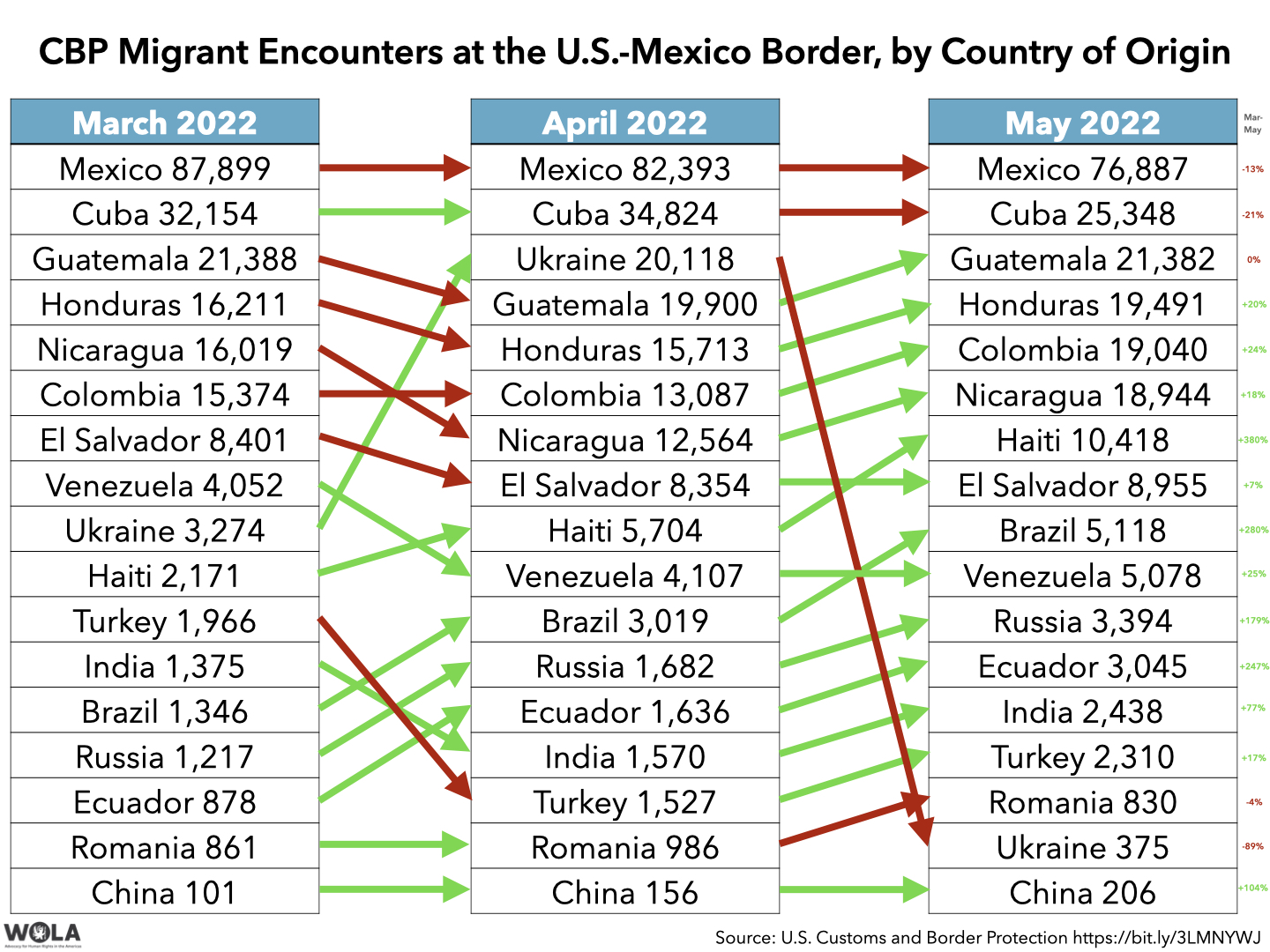

May saw the migrant population at the border diversify further. Migration from the number one and two countries, Mexico and Cuba, actually declined from April. Migrants from April’s number-three country of origin, Ukraine, declined sharply as the Biden administration’s “United for Ukraine” effort created a process for seeking refuge that no longer involved crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Migration from Haiti, Brazil, and Ecuador increased the most, in percentage terms, from March to May. Migrants from Colombia—whose citizens do not need visas to visit Mexico—climbed to fifth place, virtually tied with Hondurans.

As recently as 2019, more than 90 percent of migrants at the border were from four countries: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. That is no longer the case: these countries combined to total only 53 percent of migrants at the border in May. Only 29 percent of migrants arriving as families were Mexican, Salvadoran, Guatemalan, or Honduran.

This is a result of the pandemic increasing desperation, and migration, throughout the hemisphere. But it is also a result of how Title 42 has been implemented: because Mexico accepts expulsions of its own citizens, and citizens of the other three countries, across its land border, citizens of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras comprise the overwhelming majority of migrants expelled under the pandemic authority (94 percent in May).

Citizens of countries where expulsions or removals are difficult—because of the cost of air travel, or because of poor diplomatic relations—are expelled much less frequently. Migrants’ chances of expulsion after being encountered in the United States, and thus their ability to seek protection in the United States, vary dramatically by nationality. So far in 2022, 88 percent of Mexicans and 67 percent of Guatemalans have been expelled, compared to 4 percent of Colombians, 2 percent of Cubans, and 0.4 percent of Venezuelans.

Cuba stopped accepting flights from U.S. migration authorities in 2018 (when the U.S. stopped operations for the Cuban Family Reunification Parole program, which was resumed this past May). Nicaragua’s November 2021 decision to stop requiring visas of visiting Cubans has opened up a route through Managua, with Cubans routinely paying about $4,000 for one-way tickets there. The Biden administration pressed Mexico into agreeing to accept some land-border expulsions of Cubans and Nicaraguans, however, and about 3,000 had Title 42 applied to them in May.

Because so many migrants come from these “other” countries, CBP expelled 42 percent of migrants it encountered in May, a smaller share than had been normal. (55 percent of single adults were expelled, as were 17 percent of family unit members.)

Still, May saw the expulsion of the 2 millionth migrant from the U.S.-Mexico border since Title 42 went into effect in March 2020. The Biden administration has carried out over 77 percent of those expulsions. The administration’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sought to end the pandemic policy by May 23, 2022, but were rebuffed by a Louisiana judge hearing a lawsuit from Republican-led states.

One country, however, has seen a significant percentage of its citizens expelled by air. So far this year, CBP has applied Title 42 to 36 percent of Haitian migrants, including 30 percent of those encountered in May. Last month, the tempo of expulsion flights to Haiti increased sharply, to 36. This happened, according to the New York Times, “after renegotiating agreements with the island nation.”

Among the more than 26,000 people removed to Haiti by air during the Biden administration, many are so desperate to leave that a shady industry of charter flights has sprung up, according to a remarkable Associated Press investigation. Haitians who had earlier emigrated to Brazil or Chile and now have some migratory status there are paying thousands of dollars to be taken back, often to attempt the journey once again to the U.S.-Mexico border.

The probability of being put on a plane back to the hemisphere’s poorest nation, currently undergoing a paroxysm of gang violence, has caused many Haitians to pause in Mexican border cities rather than attempt to cross into the United States and turn themselves in to authorities. A June 12 Los Angeles Times feature documented attacks, discrimination, and lack of access to health care suffered by Haitians stranded in Tijuana, where the Haitian Bridge Alliance, a U.S. non-governmental organization, “has funded funerals for 12 Haitian migrants since December, mostly because of violence and medical negligence.”

Meanwhile, a new DHS report shows that the court-ordered revival of the “Remain in Mexico” program continues, and continues to expand. 7,259 asylum seekers, all adults, have been enrolled in the program since December 2021, of whom 4,387 have been made to wait in Mexican border towns for their hearing dates. 59 percent of those enrolled—52 percent in May—have been citizens of Nicaragua.

A report from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), which requests and shares government data, found that while most asylum cases within the program (81 percent) have been decided within six months, only 5 percent of those made to remain in Mexico have been able to find an attorney to represent them. Of 1,109 Remain in Mexico asylum cases that had been decided by the end of May, only 27—2.4 percent—ended with grants of asylum. “This is a dismal asylum success rate,” TRAC notes. “During the same period of FY 2022, fully half of all Immigration Court asylum decisions resulted in a grant of asylum or other relief.”

WOLA’s June 10 update reported that a migrant “caravan,” with several thousand mostly Venezuelan participants, was dispersing in Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas, about 25 miles from the Mexico-Guatemala border zone city of Tapachula, where it began on June 6. Thousands of participants, given documents allowing them to stay in Mexico for a month, have traveled north to seek refuge in the United States.

A June 11 statement from Mexico’s National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración – INM) reported that, following negotiations with caravan organizers, the agency provided “an immigration document certifying their stay in the country” to about 7,000 participants. The document reportedly requires migrants to leave Mexico within 30 days, during which they can travel freely through the country.

Thousands of migrants boarded buses to Mexico’s border state of Coahuila, from where more than half of the 97,696 Venezuelan migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border in fiscal year 2022 (October 2021-September 2022) have crossed. However, Coahuila’s governor, Miguel Ángel Riquelme, has sought to block their progress. Riquelme had signed an April agreement with Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R), who had sought that month to pressure Mexico into blocking migration by stepping up state vehicle inspections, snarling cross-border cargo trade for days.

Though the caravan participants had valid travel documents, Coahuila authorities turned away buses bringing as many as 2,000 to the capital, Saltillo, diverting them back to Monterrey, capital of the neighboring state of Nuevo León. Hundreds remain in the Monterrey bus station, trying to figure out where to go next. Many complain that they bought bus tickets but did not receive refunds after being blocked from boarding.

It is not clear what legal authority the local governments are using to prevent the migrants’ progress, or whether the intent is merely to meter their flow in order to prevent a mass arrival at the U.S. border. Either way, with about 8,000 migrants arriving at the border each day right now, an extra few thousand may get little notice.

In Tapachula, where the caravan began, many migrants remain stranded, made to remain in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state, while they wait for the country’s overwhelmed asylum system to adjudicate their applications. (See WOLA’s June 2 report on conditions in Tapachula.) Local media report that thousands are gathering each day outside the offices of INM and the refugee agency, COMAR, in Tapachula and in the nearby town of Huixtla, Chiapas.

Arrivals of Venezuelan migrants are likely to continue, and increase. Panama recorded 9,844 Venezuelans passing through the treacherous Darién Gap jungle region in May alone, 3.6 times more than in April, and part of an overall flow of 13,894 people last month.

This is a very dangerous part of migrants’ journeys. Doctors Without Borders, which maintains a humanitarian aid facility near where migrants emerge from the Darién Gap, has attended to 100 victims of sexual violence so far this year, and 328 last year. Colombia’s human rights ombudsman meanwhile counted 210 children traveling unaccompanied through the Darién in May, of whom 169 were apparently less than 13 years old.

“The terrain along the Southwest Border is extreme, the summer heat is severe, and the miles of desert that migrants must hike after crossing the border are unforgiving,” CBP Commissioner Chris Magnus stated in May’s migration update. As the border region enters a very hot summer, deaths from dehydration and exposure threaten to hit record levels along with record overall migration.

In the El Paso sector, Border Patrol has installed more solar-powered rescue beacons that make it more possible for lost or dehydrated migrants to call for help. This, the Morning News reports, has kept fatalities from being much worse. In Arizona, Border Patrol announced on June 9 that it is piloting a new “heat mitigation effort,” handing out “Heat Stress Kits/Go-Bags that will be distributed to 500 agents” at two desert stations.

Drownings in the Rio Grande, and in irrigation canals, remain severe.

Falls from especially high new segments of the border wall continue to cause a higher death toll, as the Washington Post reported in April. A June 15 CBP statement documented the May 6 death of a man who fell in the space between two layers of fencing between San Diego and Tijuana.

A series of feature stories in U.S. and U.K. media this week have explored aspects of a troubled institutional culture at the Border Patrol. The agency has faced serious human rights abuse allegations, while its membership (as evidenced by the posture of its union, which claims to represent 90 percent of agents) detests the Biden administration’s approach to border security and migration.