With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

On September 1, about a mile downstream of the border bridges between Piedras Negras, Coahuila and Eagle Pass, Texas, a large group of migrants attempted to cross a Rio Grande swollen by recent rains. CBP reported as of September 3 that nine members of this group died by drowning in the river. A September 3 tweet from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Commissioner Chris Magnus referred to “13 lives lost yesterday while they attempted to cross the Rio Grande River at Eagle Pass.”

The nationalities of the deceased have not been reported. U.S. personnel reported rescuing 37 members of the group from the river, while Mexican authorities apprehended 39 on the Coahuila side. The Washington Post reported that the tragedy “appeared to be the deadliest mass drowning along the border in years.” The Eagle Pass fire chief told the New York Times that U.S. and Mexican authorities recovered 12 bodies from the river in a single day (in separate events) about 2 months ago, adding that drownings are an everyday event there.

Eagle Pass is one of two major (over 30,000 population) towns in Border Patrol’s Del Rio Sector, in a rural area of mid-Texas. (Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico land border into nine sectors.) Once a quiet part of the border, Del Rio was the border’s number-one sector for CBP migrant encounters in January, June, and July of this year.

More than half of migrants encountered in Del Rio (70 percent of them in July) come from countries other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. Two thirds in July came from Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Colombia. Citizens of those countries are led to cross in Del Rio (and in Yuma, Arizona) by word of mouth—but also by smuggling organizations. “What we know with absolute certainty is that the smuggling organizations control the flow,” the chief of Border Patrol’s Tucson, Arizona Sector told the Associated Press in a story reported this week from Yuma.

2022 is already the worst year on record for deaths of migrants on the U.S. side of the Mexico border, punctuated by tragedies like the June asphyxiation death of 53 people in a cargo container, and several hundred fatal cases of dehydration and exposure in deserts, dozens if not hundreds of drownings in rivers and canals, and numerous falls from the border wall. A 5-year-old Guatemalan girl drowned near El Paso, Texas on August 22. That week, Border Patrol encountered two unaccompanied Guatemalan girls, aged four and one years old, near Ajo, Arizona. The remains of 28 Guatemalan migrants, found at different locations this year, are currently in the morgue of McAllen, Texas, awaiting final certification of their identities.

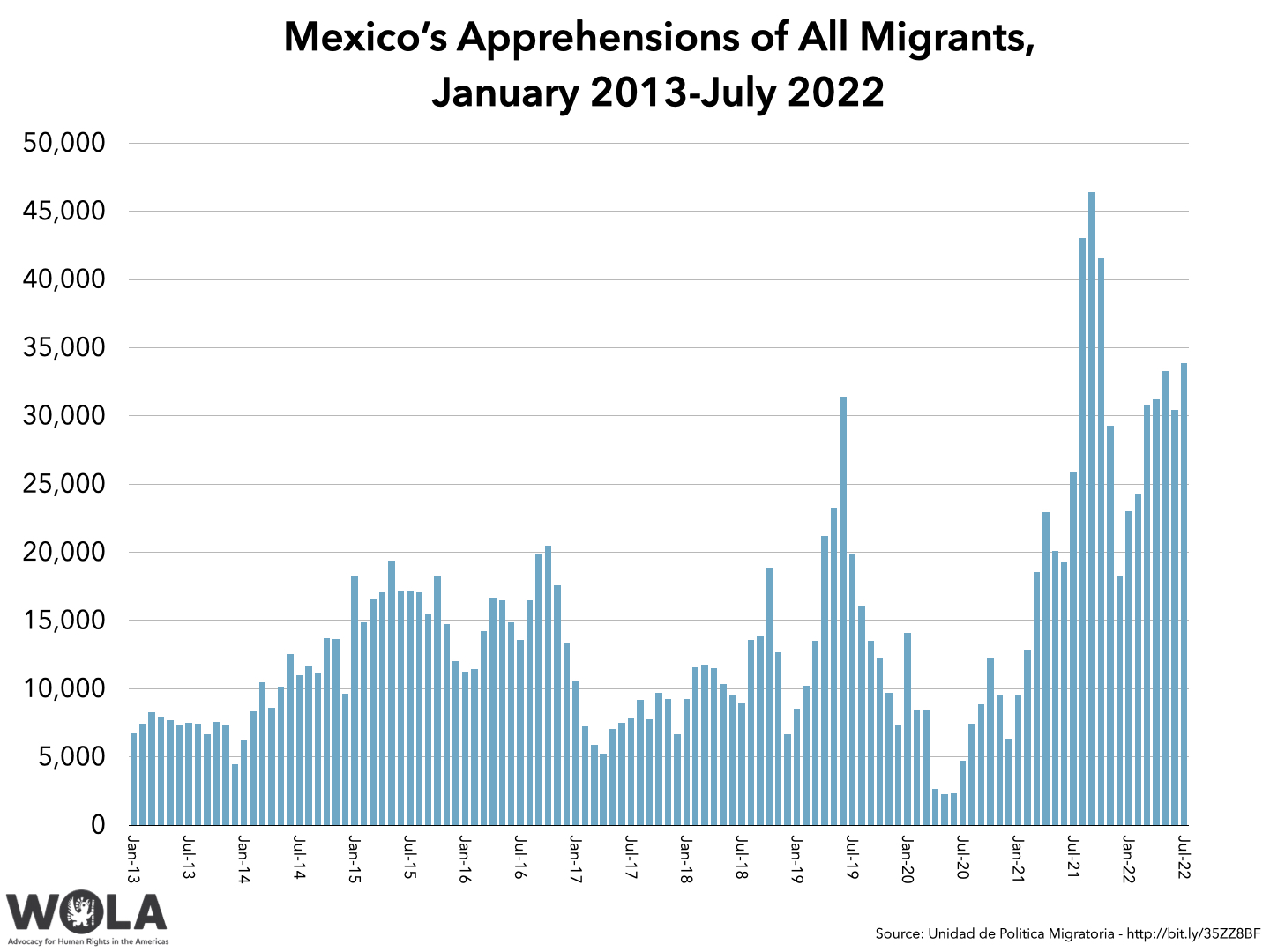

Mexico’s migration authorities apprehended their fourth largest-ever monthly total of undocumented migrants in July—33,848 people—according to data posted in late August.

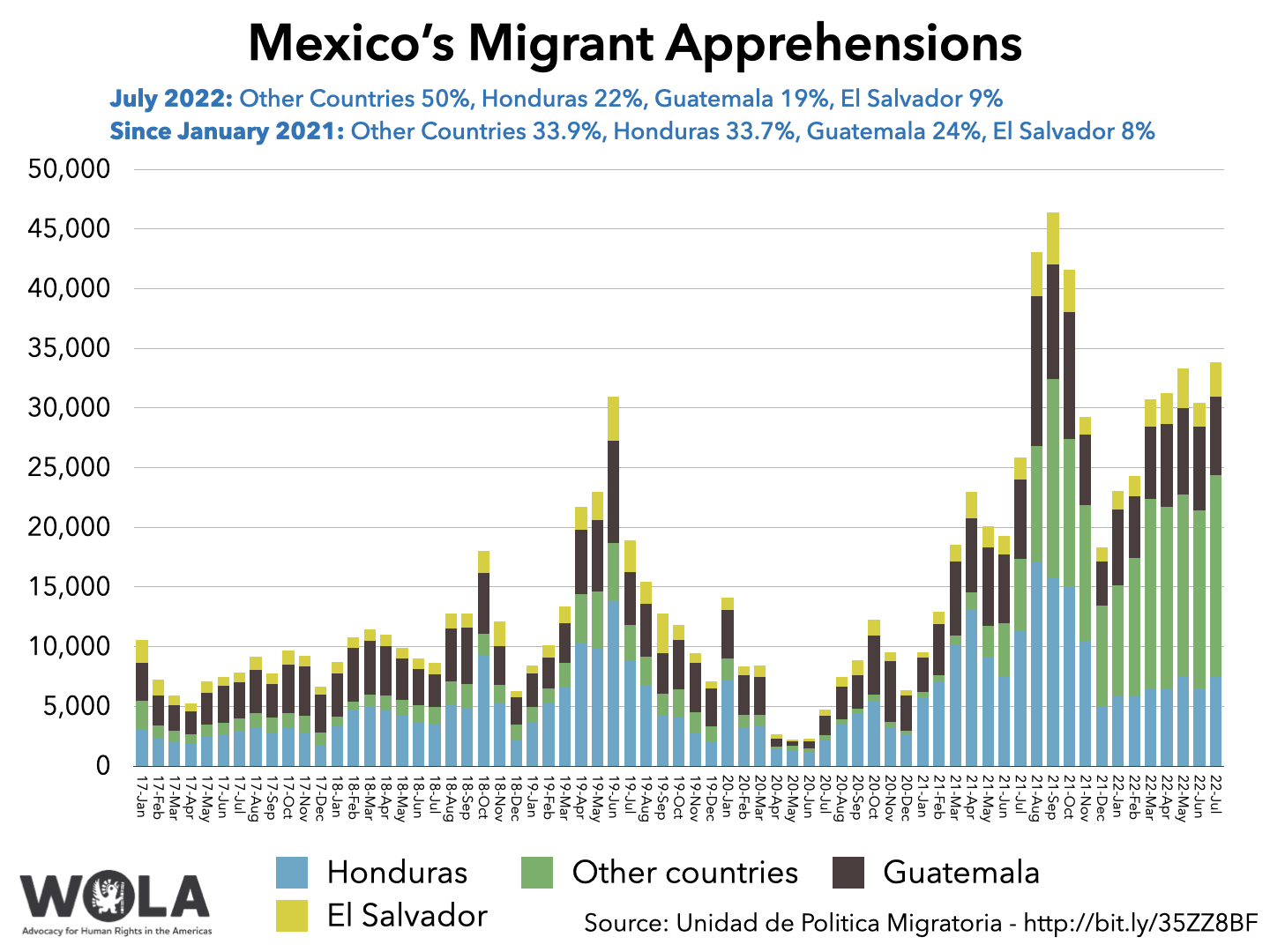

For the first time, fully half of those apprehended were not from Central America’s so-called “Northern Triangle” countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras). As recently as 2018, 87% of Mexico’s apprehended migrants came from those countries. The countries whose migrants Mexico apprehended over 1,000 times in July were, from most to least: Honduras, Guatemala, Venezuela, El Salvador, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Colombia.

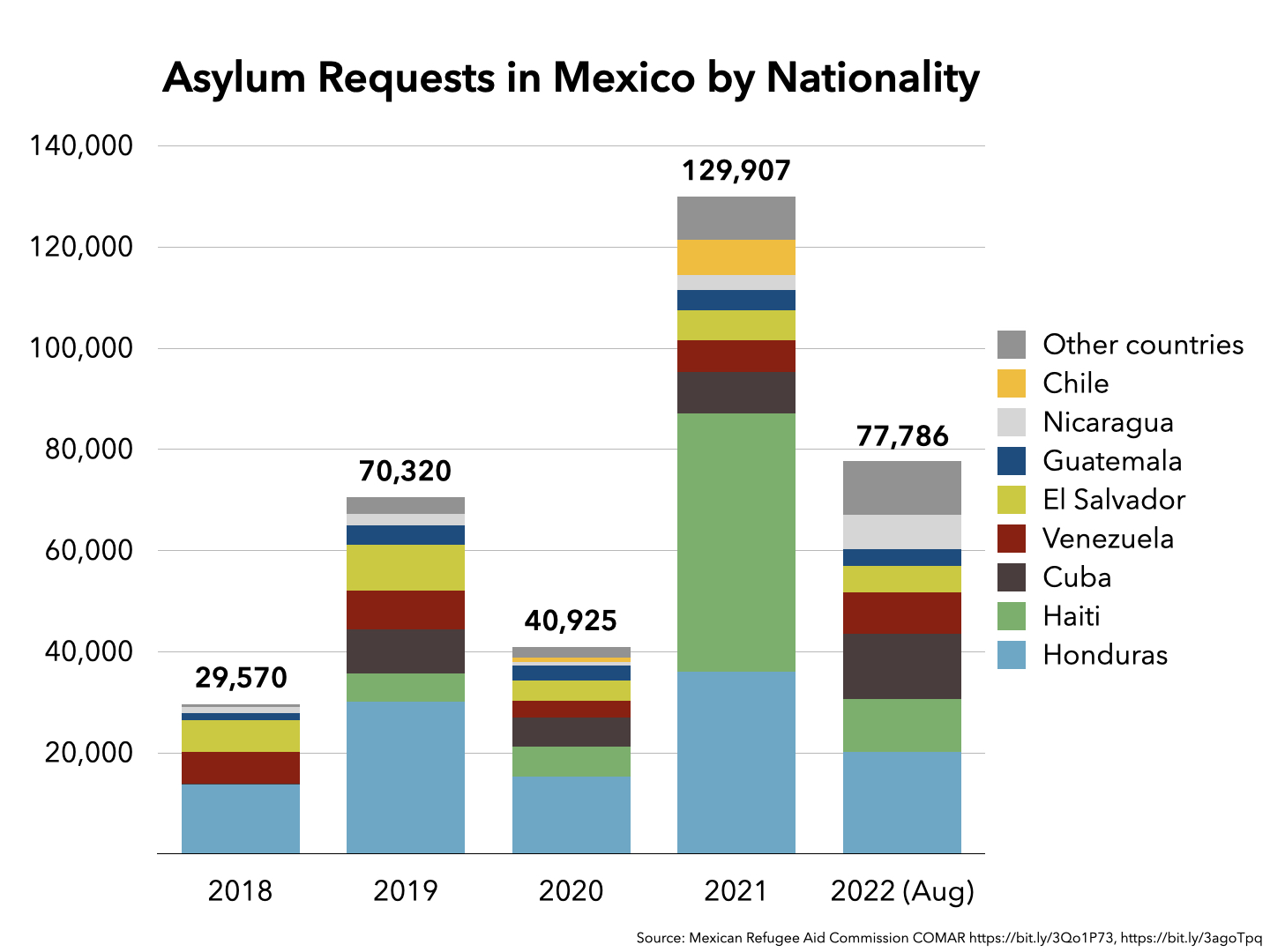

For the month of August, Mexico’s refugee agency (Mexican Refugee Aid Commission, COMAR) reported receiving its largest number of asylum applications since March. 10,763 people applied for asylum in Mexico last month, boosting COMAR’s annual total to 77,786—already its second-largest asylum total ever. (COMAR received nearly 130,000 applications last year.)

The countries whose migrants have sought asylum in Mexico over 3,000 times in 2022 so far are, from most to least: Honduras, Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Applications from Nicaragua, Cuba, Venezuela, Colombia, and “other countries” already exceed their 2021 full-year totals.

Mexico, meanwhile, is increasingly using its military to interdict migrants. This is part of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s overall drive to increase the military’s role in Mexican life. That drive includes a bill nearing passage in Mexico’s Congress that would place the National Guard, a militarized police force established in 2019, firmly within the military chain of command. A September 2 WOLA commentary warns that this step will give the armed forces “more and more power vis-à-vis civilian authorities.”

The Mexican Presidency’s latest annual “report on activities” offers statistics about the armed forces’ migration role, summarized by journalist Manu Ureste at Animal Político. The Army, Marines, and National Guard reported collaborating in the apprehension of 345,584 migrants between September 2021 and June 2022. Three-quarters were apprehended by the Army. Ureste notes that—for unclear reasons—this is more than the 309,430 migrants that Mexico’s civilian migration agency (National Migration Institute, INM) reported apprehending during those months.

46,916 military and National Guard personnel are currently deployed on counter-migration missions in Mexico right now, a 46 percent increase over 2021. Of those, 23,458 are marines (a 46 percent increase over 2021); 14,013 are army soldiers (a 2.5 percent increase); and 9,445 are guardsmen (a 296 percent increase).

Although the National Guard can check immigration status, formally, military personnel are not supposed to be detaining migrants: that is the task of the INM, a force that does not carry lethal weapons. Soldiers are meant to provide perimeter security for INM operations and to man checkpoints. However, as Ureste points out, human rights organizations have been pointing out since 2015 that military and police personnel are playing active roles in arresting migrants.

“In administrative terms, it is the INM who makes the detention,” Alberto Xicoténcatl of the Saltillo, Coahuila migrant shelter told Animal Político. “But in practical terms, those who carry out the operations to detain migrants, those who chase them and put them in the detention vans, are directly the National Guard or the Army.” Adds Yuriria Salvador of the Tapachula, Chiapas-based Fray Matías Migrant Rights Center, “It is very visible that the National Guard has become the armed wing of the INM and the executor of a migration policy based on containing and detaining migrants and asylum seekers, and on militarizing the Institute.”

From January to August, Jeff Abbott reported at Foreign Policy, Mexico had deported 26,557 Guatemalans by land. (The official statistic for all Mexican deportations of Guatemalans, including flights, is 28,826 during the first 7 months of 2022.) Abbott notes that almost no services are available to returned Guatemalans: “The extent of the attention they receive essentially ends once they leave the reception center.” The difficulty of crossing Mexico has increased smugglers’ fees to an average of US$15,500 “for a package that includes multiple attempts to cross the Mexico-U.S. border.”

Amid news of a “caravan” of several hundred migrants leaving Honduras and bound for the United States via Guatemala’s southern border, Guatemala’s migration authority (Guatemalan Migration Institute, IGM) declared itself on “orange alert.” Migration agents, in coordination with security forces, carried out an operation that, as of September 5, had removed 548 migrants back across the border into Honduras. (Guatemala has expelled about 11,000 migrants into Honduras so far in 2022.)

The IGM reported that 361 of the removed migrants were Venezuelan, 60 were Honduran, and 56 were Cuban. Other nationalities mentioned include Haiti, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, and Cameroon. One woman from Angola was detained while walking barefoot, her feet bleeding.

Under a longstanding migratory agreement, citizens of Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador can enter Guatemalan territory without a visa or passport, just showing their national identity cards. The IGM noted that it expelled the Honduran members of this most recent group, though, because they did not cross in an official manner.

On the other side of Guatemala’s border with Mexico, in Chiapas, migrants stranded in the border-zone city of Tapachula have organized about 12 so-called “caravans,” each approximately 200 to 500 people, in the space of just over two weeks. Their destination appears to be Tapanatepec, in Oaxaca state, the first crossroads town one hits after leaving Chiapas along the Pacific coastal highway from Tapachula, 180 miles away.

Word of mouth has spread that in that town, over the past month and a half, an INM facility has been handing out Multiple Migratory Forms (FMMs, basically tourist cards) allowing undocumented migrants to be in Mexico for 30 days.

With an FMM, migrants have a documented status allowing them to board buses and travel through Mexico, including to the U.S. border zone. Migrants told the online journalism outlet Desinformémonos that word of mouth tells them to go to areas in Mexico’s northern-border zone where Mexican authorities are less likely to take migrants’ FMMs and “rip them up in your faces.”