With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

“Effective immediately,” the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced on October 12, “Venezuelans who enter the United States between ports of entry, without authorization, will be returned to Mexico.” A release from Mexico’s Foreign Ministry confirmed that these returns will be expulsions across the land border under Title 42.

Title 42 is a measure that U.S. authorities, in the name of limiting COVID-19’s spread, have used to quickly expel migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border over 2.2 million times. Often, these expulsions deny migrants the right to ask for asylum in the United States. Land ports of entry along the border remain closed to most asylum seekers.

The Trump administration first implemented Title 42 in March 2020. The Biden administration maintained it, then planned to suspend it in May 2022 amid declining COVID cases. A lawsuit brought by Republican state attorneys-general prevented that May suspension. Now, the Biden administration is fighting for the right to suspend Title 42 even as it expands its application to Venezuelan citizens.

As of October 12, Mexico is accepting U.S. Title 42 land-border expulsions of citizens of five countries: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and now Venezuela. Citizens of those first four countries have made up 99 percent of recent months’ Title 42 expulsions, since land-border expulsions are cheaper and easier—both logistically and diplomatically—than expulsions by air.

As the first reports emerged of disoriented, homeless migrants returned to Mexican border cities, human rights and migrants’ rights defenders were quick to criticize the new measure. Migrants expelled to Mexico under Title 42 have been subjected to thousands of known cases of assault, rape, kidnapping, robbery, and other violent attacks. WOLA called out the Biden administration for a policy that “seeks to bring the numbers down at all costs rather than adopting measures to reopen the border to access asylum or other forms of protection,” and faulted the Mexican government for a step that “once again demonstrates its willingness to do the U.S. bidding on migration enforcement, even at the expense of the safety and well-being of migrants and asylum seekers.”

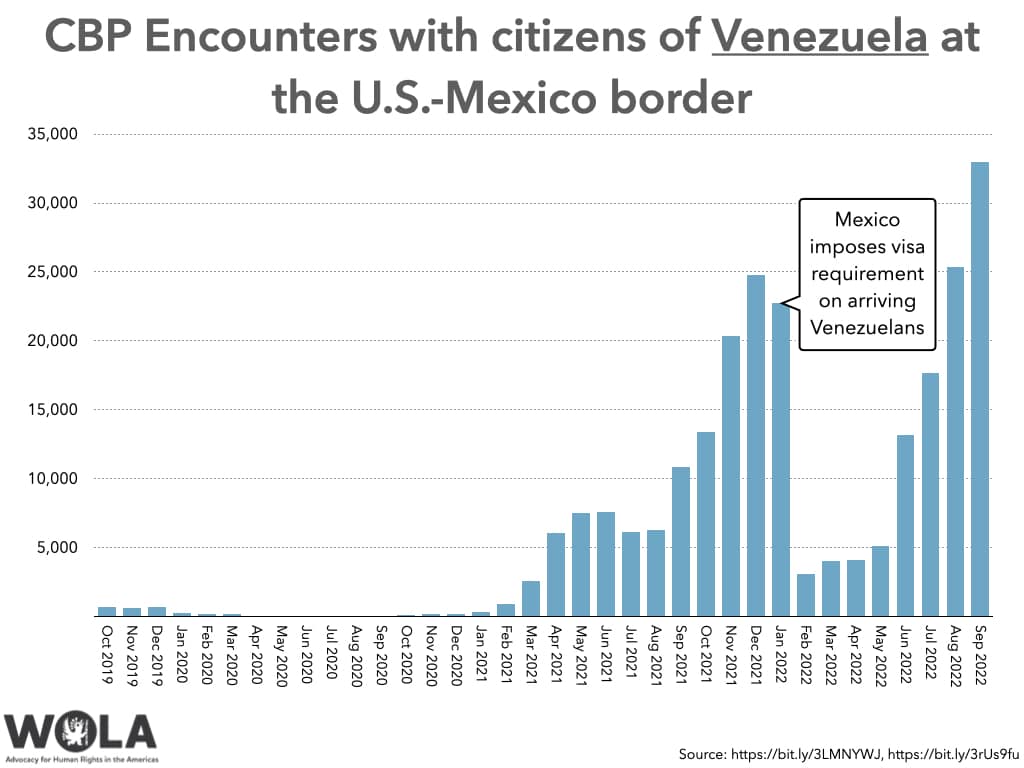

The Biden administration pushed to include Venezuelan citizens because of a sharp recent rise in arrivals of Venezuelan citizens at the U.S.-Mexico border. U.S. border authorities had encountered 153,905 Venezuelans during the first 11 months of the government’s 2022 fiscal year (October 2021-August 2022), and DHS’s release revealed that 33,000 more Venezuelans arrived at the border in September, for a full-year total of about 187,000 Venezuelan migrants. Citizens of Venezuela were the second most-encountered nationality at the border in August and September. The only other countries whose citizens have ever been encountered at the border 33,000 or more times in a single month are Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and (once, in April 2022) Cuba.

Texas Public Radio reported that “up to 660 Venezuelans have been crossing every day in El Paso alone.” This has strained the city’s short-term migrant shelter capacity, reduced when its principal humanitarian nonprofit, Annunciation House, closed the largest shelter in its network earlier this year “due to maintenance issues and a lack of volunteers,” the Guardian reported.

Along with the Title 42 expansion, DHS announced a humanitarian parole program for up to 24,000 Venezuelan refugees. As 33,000 Venezuelan migrants arrived at the border in September, this program would benefit a number equal to about 3 weeks of the current flow.

The new mechanism is somewhat similar to the “Uniting for Ukraine” program for Ukrainian refugees. Venezuelans may apply online and, if approved, receive humanitarian parole, with eligibility to apply for work authorization and asylum, and the ability to fly to an airport in the U.S. interior.

To benefit, on a “case by case basis,” the Venezuelan applicant must pass criminal and biographical background checks and have “a supporter in the United States who will provide financial and other support.” They will be rejected if they have been removed from the United States during the past five years, or if they entered Panama or Mexico, or improperly crossed the U.S. border, after October 12. The program will continue only if Mexico keeps taking expelled Venezuelans under the Title 42 “public health” authority.

“The administration initially considered a broader program that would have provided safe passage to Haitians, Cubans and Nicaraguans as well as Venezuelans,” The Wall Street Journal reported, citing “people familiar with the situation.” However, the White House and DHS “ultimately pared the concept back.”

It is not clear what Mexico’s government may get in exchange for accepting the expulsion of thousands of migrants into its border cities, though Mexican officials may view it as a deterrent to future migration through their territory. The Biden administration did announce an increase in H-2B temporary work visas: 65,000 more, including 20,000 more for citizens of northern Central America and Haiti. That would roughly double the number of visas available under the H-2B program. (A November 2021 report from the Migration Policy Institute explains the H-2A and H-2B visa programs.)

About 7.1 million Venezuelan people have left their country in recent years, nearly a quarter of the total population. 80 percent had settled elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), a project jointly run by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), published a 252-page report on October 12 about the situation of Venezuelan migrants around Latin America and the Caribbean. It found that three-quarters of Venezuelans living elsewhere in the Americas “face challenges accessing food, housing and stable employment.” Half of them “cannot afford three meals a day and lack access to safe and dignified housing.”

Migration of Venezuelans to the U.S.-Mexico border was uncommon until 2021, after region-wide COVID-19 travel restrictions eased. Then, Venezuelans began arriving by air to Mexico, which at the time did not require them to obtain visas, then traveling to the U.S. border and turning themselves in as asylum seekers. Their numbers steadily increased; in December 2021, U.S. border authorities encountered over 24,000 Venezuelan citizens.

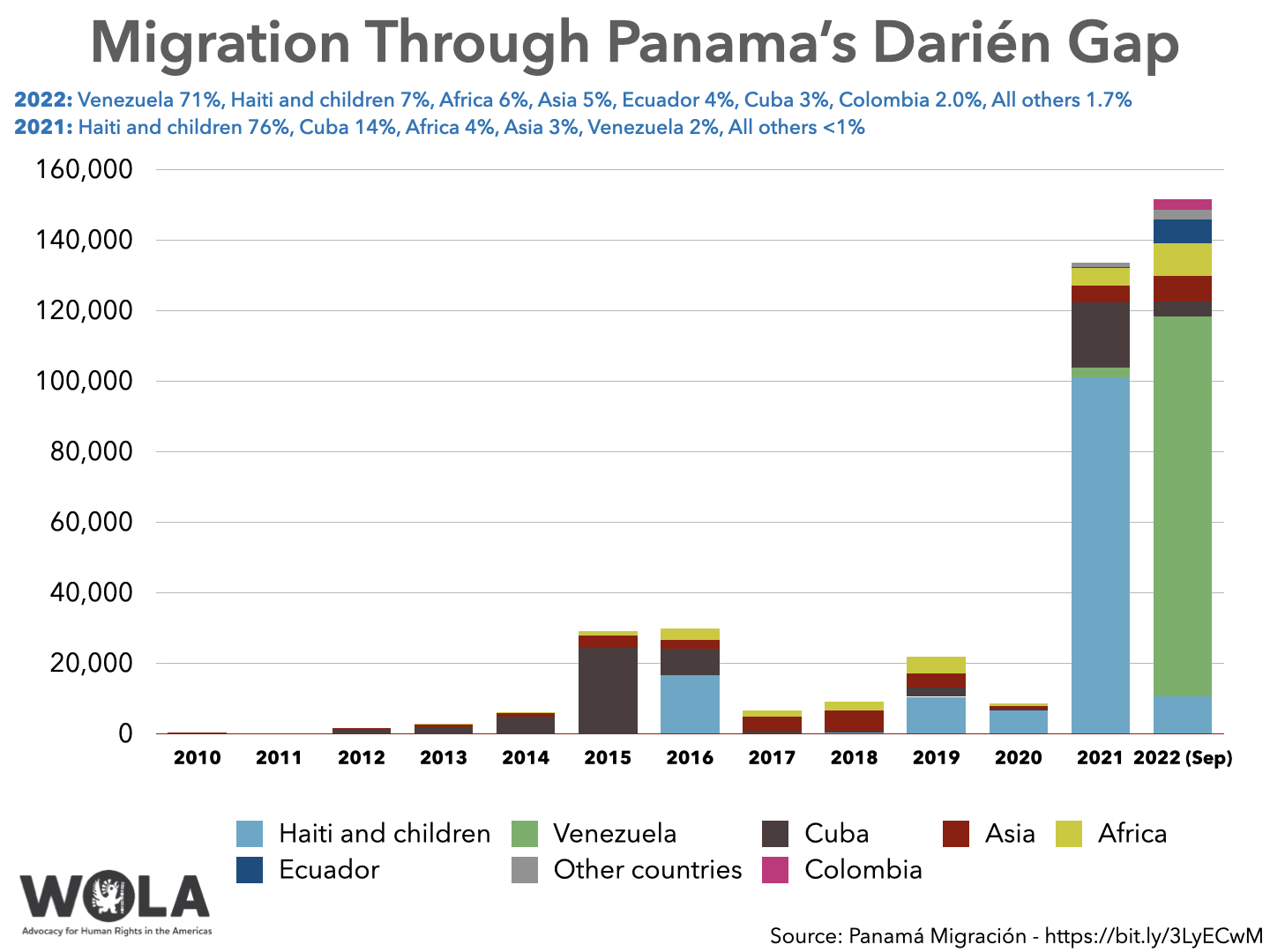

In January 2022, Mexico—at strong U.S. suggestion—began requiring visas. By March, authorities in Panama were detecting sharp increases in overland migration of Venezuelans. Migrants were passing on foot through the Darién Gap wilderness, once regarded as impenetrable. The International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) representative in Panama told Agénce France Presse that while many of these Venezuelan overland migrants have been living elsewhere in South America, a growing portion are now coming directly from Venezuela.

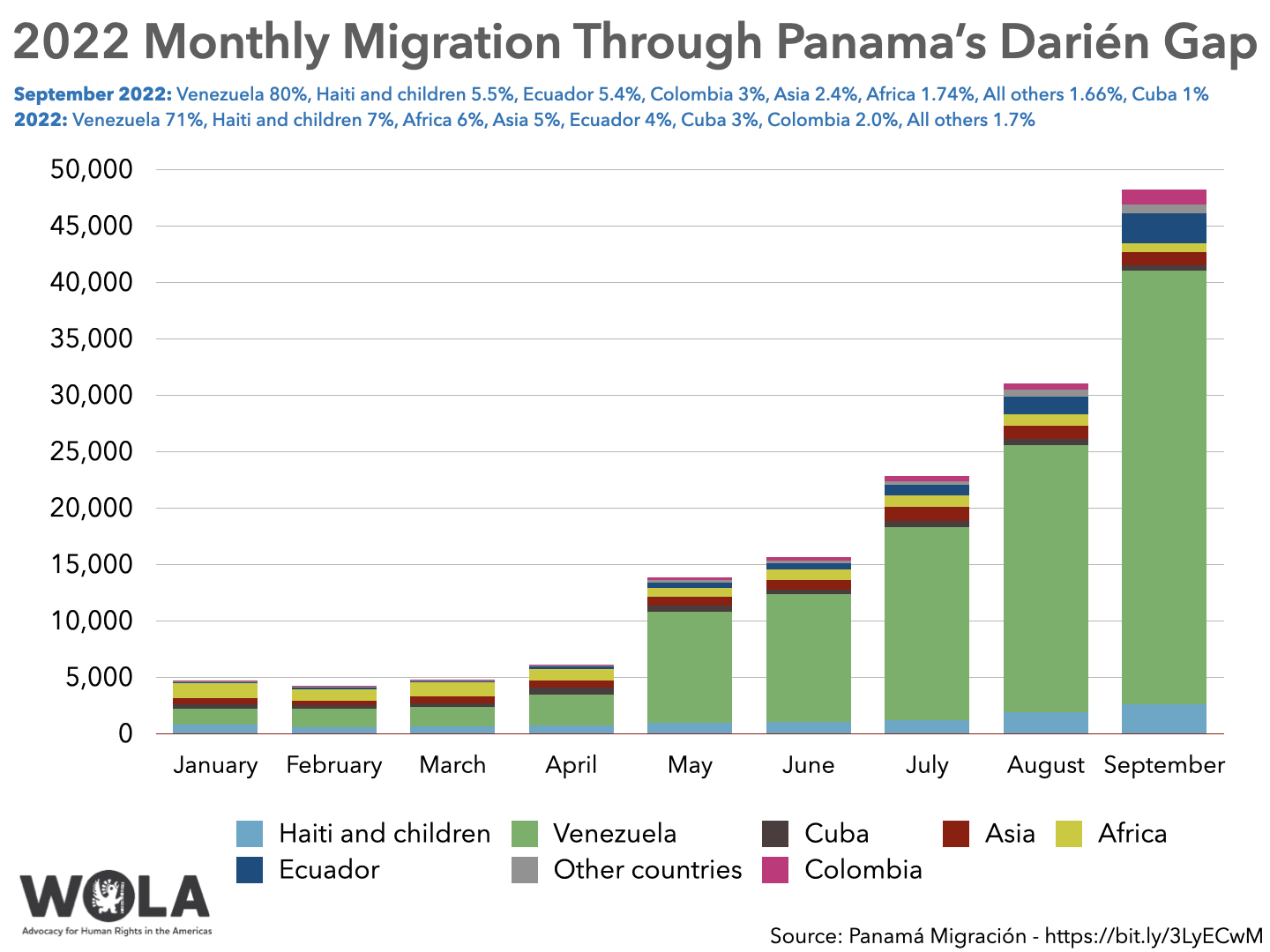

The government of Panama published data on October 10 about migration through the treacherous, ungoverned Darién Gap region. This region of old-growth jungle, straddling eastern Panama and northwestern Colombia and forming a break in the Pan-American Highway, saw a record number of migrants walk through in September: 48,204 people, of whom 80 percent (38,399) were citizens of Venezuela. During the first nine months of 2022, a record 151,582 people passed through the Darién Gap, 107,692 of them Venezuelan.

Colombia’s human rights ombudsman’s office reported that during the final seven days of September, 14,000 migrants—2,000 per day—departed Colombia for the Darién. That was up from 12,000 migrants the previous week. Now, reads the DHS statement announcing Title 42 expansion for Venezuelans, “Panama is currently seeing more than 3,000 people, mostly Venezuelan nationals, crossing into its territory from Colombia via the Darién jungle each day.” If accurate, that could add up to 90,000 or even 100,000 migrants in this ecologically fragile region in a single month.

“15 percent of the migrants are children and adolescents,” reported Colombia’s El Espectador on October 12. “In the last 15 days, about 4,290 minors have passed through.” About 9,000 migrants are currently in the northwestern Colombian port of Necoclí, where they wait several days for boats to take them across the Gulf of Urabá to the Darién region.

The 60-plus-mile journey is dangerous. Migrants perish from drowning, disease, animal attacks, or assault from criminal groups. Panama’s Migration Service (Senafront), which maintains little presence along the jungle trail, counts 123 deaths so far in 2022, mostly from drownings, but the actual number is unknown. “Between 10 and 15 percent of migrants crossing the Darien Gap suffer sexual violence,” reported the Voice of America, citing the Panamanian Red Cross. An October 7 New York Times feature, with a series of vivid images by photographer Federico Ríos, documented the misery of migrants’ journey through the Darién region.

As recently as 2011, Panama detected only 283 people crossing through the Darién Gap all year. Only 219 Venezuelans took this route in all 11 years from 2010 to 2020. The region experienced a modest wave of Cuban migration in 2015-2016, and more than 100,000 Haitian migrants (including their South American-born children) in 2021. This year, though, is breaking all records.

The DHS announcement of Title 42’s application to Venezuelans adds, “The United States is also planning to offer additional security assistance to support regional partners to address the migration challenges in the Darién Gap.” This will likely increase an already robust package of U.S. equipment and training for Panama’s Senafront. “The United States and Mexico are reinforcing their coordinated enforcement operations,” the DHS statement adds, “to target human smuggling organizations and bring them to justice.”

A U.S. State Department fact sheet presented highlights of an October 6 meeting of 21 Western Hemisphere countries’ foreign ministers in Lima, Peru, alongside the OAS General Assembly session occurring there. The ministers, including U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, were discussing steps taken to implement commitments to manage region-wide migration, made during the June Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. Eleven “action package committees” are overseeing these commitments, across four “pillars” laid out in the June Los Angeles Declaration.

The fact sheet laid out a few categories of U.S. assistance for regional migration:

Mexico’s migration authority (National Migration Institute, or INM), reported apprehending nearly 6,000 migrants throughout the country in 2 days, on October 7 and 8. That rate, if sustained throughout October, would bring the INM near 100,000 monthly migrant apprehensions. Mexico’s single-month apprehensions record, set in September 2021, is less than half of that (46,370). WOLA’s October 7 Border Update noted that Venezuelan citizens made up 40 percent of Mexico’s 42,408 migrant apprehensions in August.

Mexican human rights defenders have meanwhile been voicing alarm about proposed changes to the country’s immigration law that would give the armed forces a greater role in migrant apprehensions. The proposal, floated by Attorney-General Alejandro Gertz Manero, whose work often draws criticism from human rights groups, would allow Mexico’s National Guard personnel to inspect and detain undocumented migrants on their own, without the presence of INM agents as the law currently requires.

The National Guard is a militarized police force created by the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2019. Though created as a “civilian” force, most of its membership came from the armed forces. In September, at López Obrador’s behest, Mexico’s Congress passed legislation to de-civilianize the National Guard completely, placing it under the military chain of command as a new branch of the armed forces and removing all members who had been transferred from Mexico’s now-defunct Federal Police. Now, Attorney-General Gertz is proposing to give these military personnel the capacity to apprehend migrants with no civilian involvement.

The dangers to human rights of giving the military a greater role in migration control were the subject of Bajo la Bota (“Under the Boot”), an in-depth report published in May by several prominent Mexican human-rights, migrant-rights defense groups, and journalists. The report warns of mistreatment of migrants, at times violent, at the hands of migration and security forces; blockages to the right to seek asylum; extortion and kidnapping enabled by corrupt government personnel; and the especially grave effects on women migrants and migrants of color.

“We’ve heard stories of abuse at airports during searches by the National Guard, we also collected testimonies, for example, of women who had been victims of rape in immigration stations by the National Guard, and a large number of women who have been victims of arbitrary detention also by the National Guard,” Ana Lorena Delgadillo of the Foundation for Justice, one of the Bajo la Bota report’s co-publishers, told Mexico’s SinEmbargo. She noted that of the INM delegations in each of Mexico’s 32 states, 19 are now headed by people with military backgrounds.

Mauro Pérez Bravo, president of the INM’s Citizens’ Council, an oversight body, also voiced alarm at Attorney-General Gertz’s proposal for INM to maintain a registry of human rights defenders. “That is, a kind of accreditation that says ‘you are a human rights defender.’ We see that as a kind of criminalization of the defense of human rights,” Pérez told Mexico’s Proceso magazine.

In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott (R), up for re-election in November and a critic of the Biden administration, has spent over $4 billion in state funds on a series of border-hardening and migrant detention and transportation measures that he calls “Operation Lone Star.” These activities continued to draw significant media attention over the past week.