With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

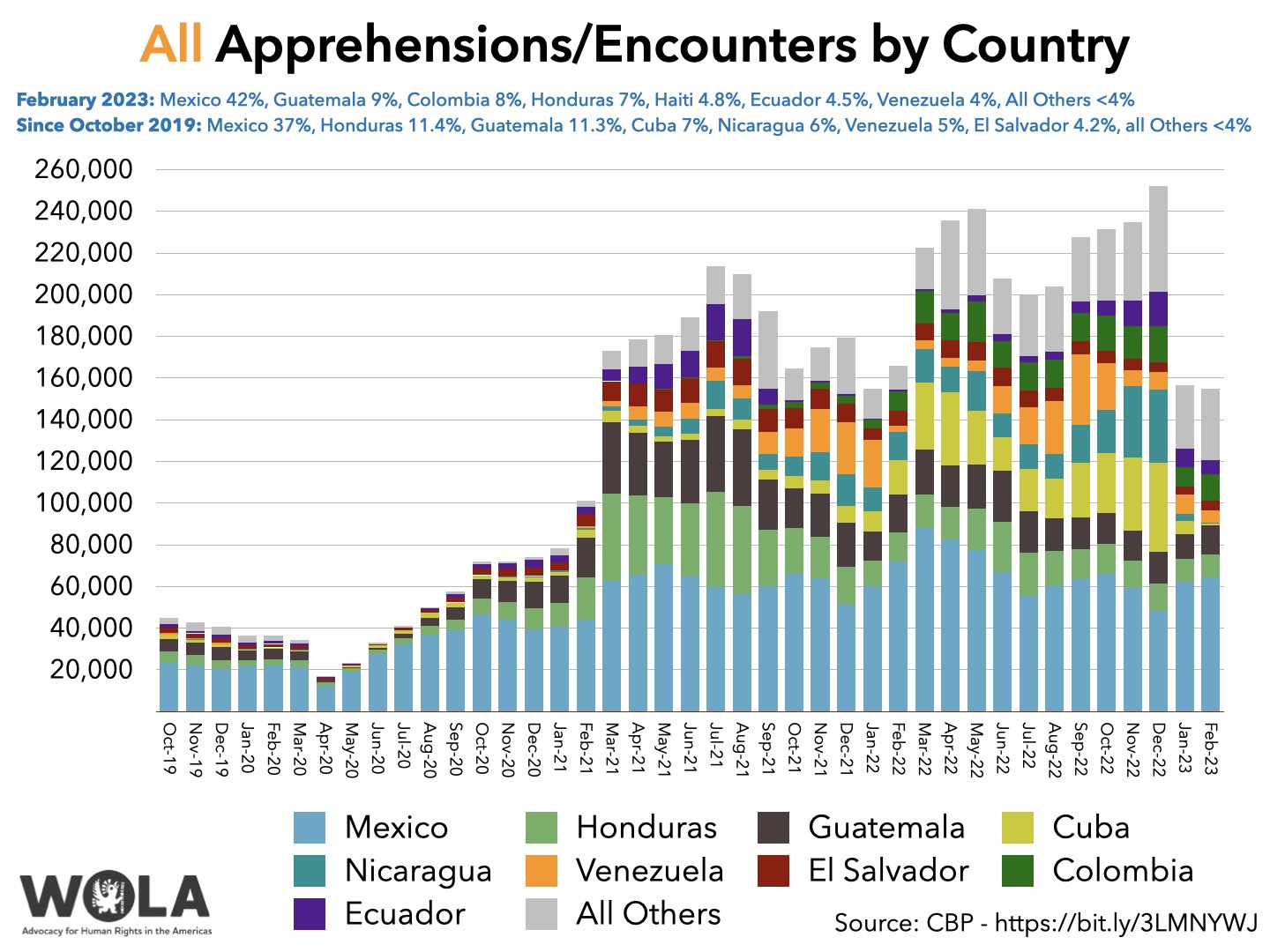

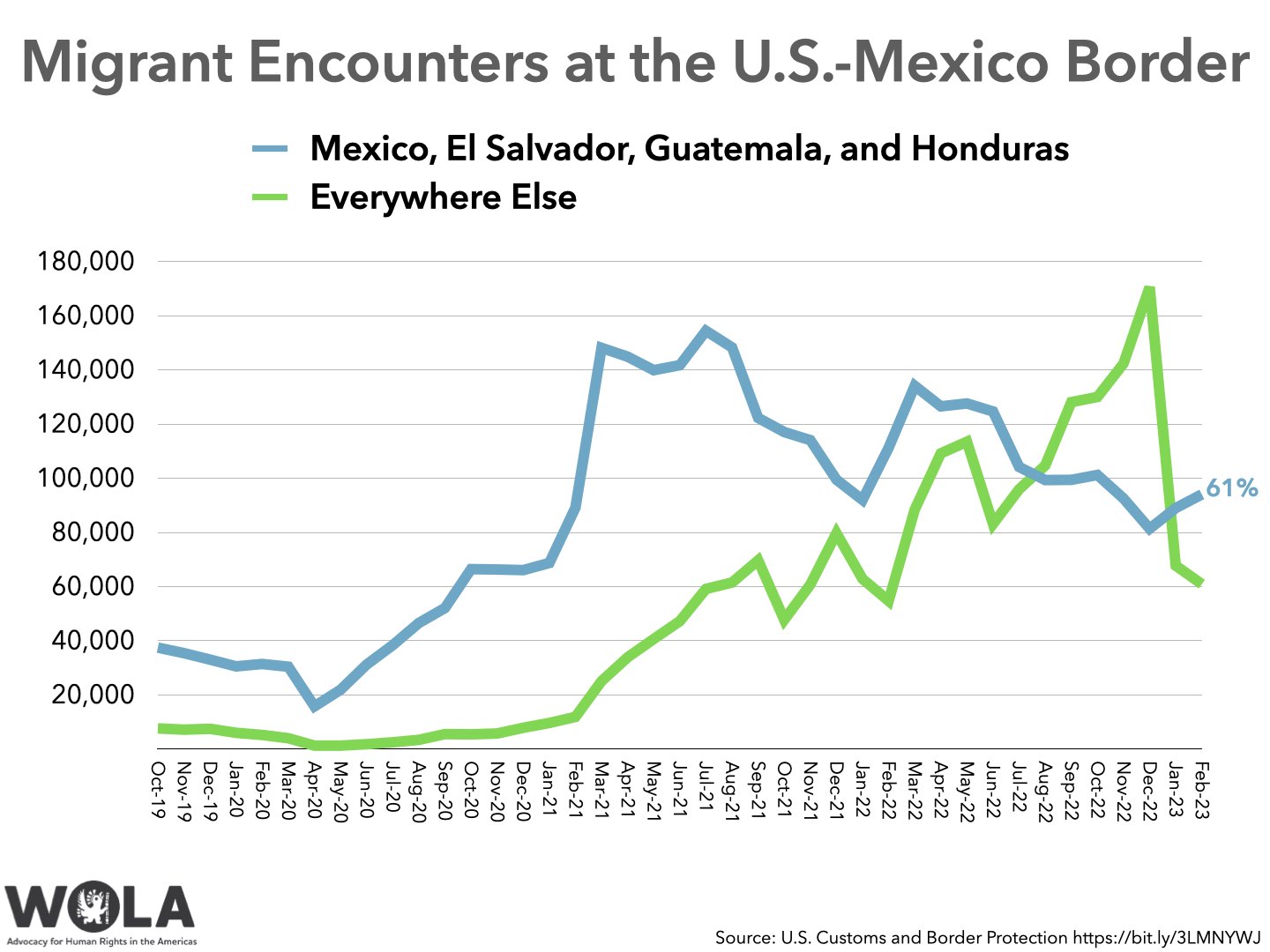

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published data on March 15 showing that, after declining 40 percent from December to January, the number of migrants whom U.S. authorities encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border remained similar in February. (See WOLA’s February 17 Border Update for a discussion of the January decline.)

Border Patrol encountered 128,877 undocumented migrants in border zones between ports of entry in February, almost identical to the 128,913 migrants the agency encountered in January (a month that, of course, is 3 days longer). Another 26,121 undocumented migrants came to land-border ports of entry, most of them with appointments to seek asylum, adding up to a border-wide total of 154,998 migrants.

Of that total, 39,206—25 percent—were what U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) calls “repeat encounters”: individuals whom the agency or its Border Patrol component had encountered at least once in the past 12 months. The agency actually encountered 94,124 unique individuals in February, a 13 percent drop from January.

The drop made February 2023 the second-lightest month of migration since the Biden administration’s first full month, February 2021. In El Paso, CBS News reported, shelters are “no longer severely overcrowded.”

The likely reason for the lower numbers continues to be the near-impossibility of gaining access to asylum for citizens of Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. All of these eight countries’ citizens are subject to rapid expulsion back into Mexico—whose government accepts them—using the Title 42 pandemic authority.

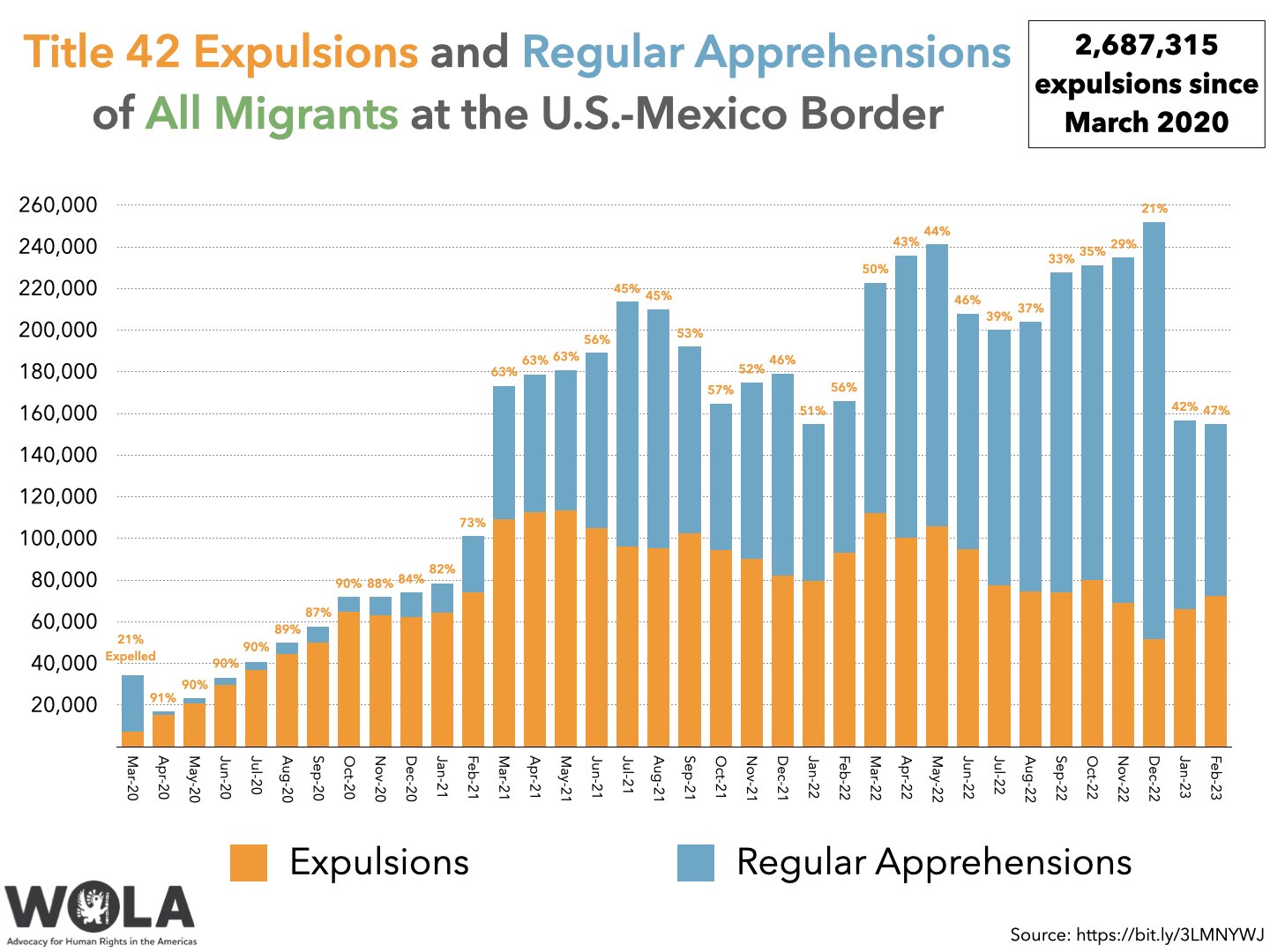

That authority, which will be three years old on March 20, is set to expire on May 11. The Biden administration convinced Mexico to add Venezuelan citizens to the list of “expellable” nationalities in October 2022; Cuba, Haiti, and Nicaragua were added in early January 2023. The difficulty of accessing asylum appears to have discouraged numerous asylum seekers, regardless of the threats they may be fleeing.

CBP applied Title 42 to migrants 72,591 times in February, the most since October 2022. That means 47 percent of migrant encounters ended in expulsions, the largest percentage since March 2022. Since its inception in March 2020, CBP has used Title 42 to expel migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border 2,687,315 times.

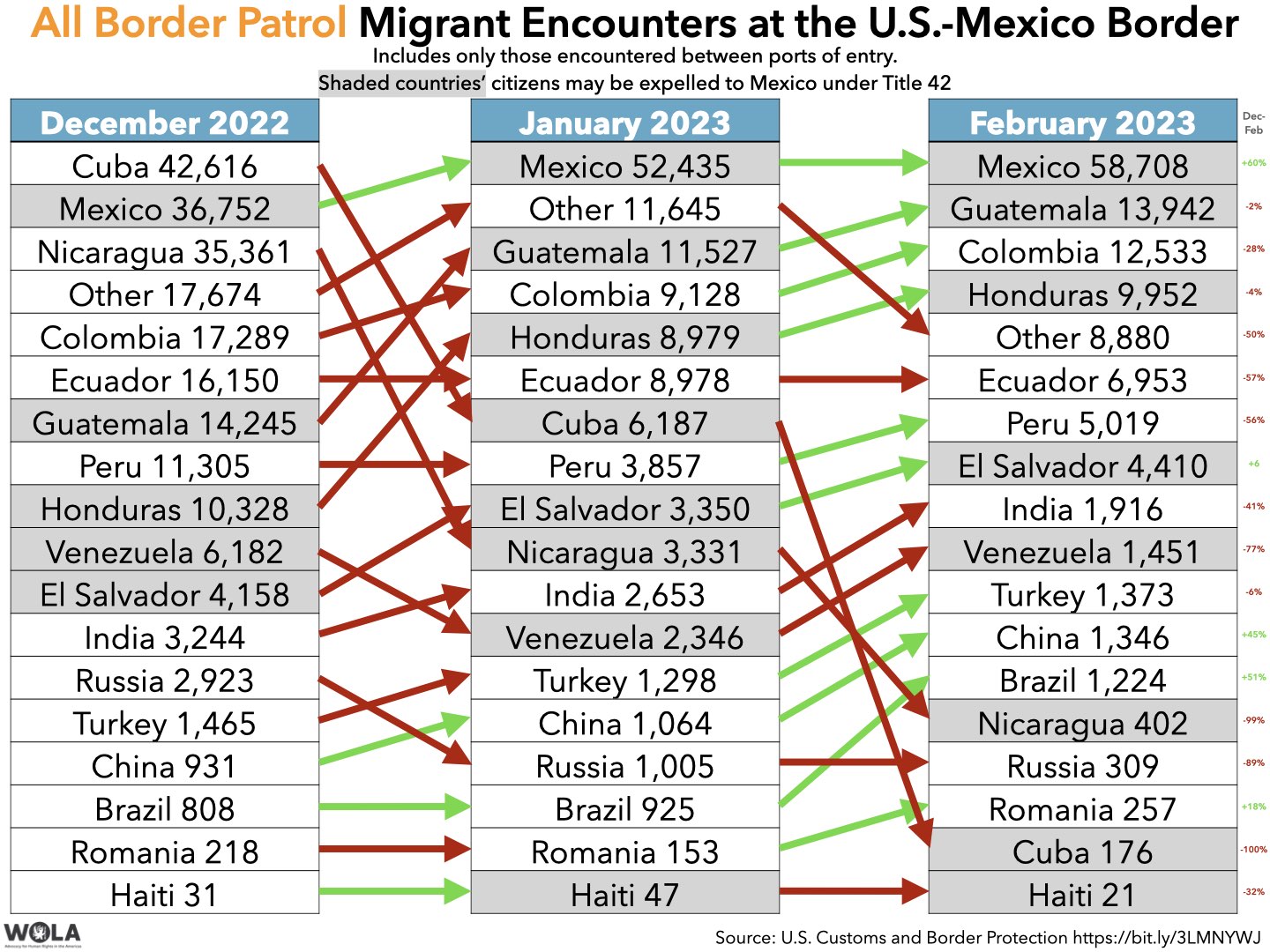

Between the ports of entry where Border Patrol operates, migration plummeted from the four countries most recently subject to Title 42 expulsion into Mexico (Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela). Border Patrol encounters with citizens of Cuba fell 99.6 percent from December to February, from 42,616 to 176 (although maritime encounters saw a dramatic increase, as discussed below). Encounters with Nicaraguan citizens dropped 99 percent from December (35,361 to 402).

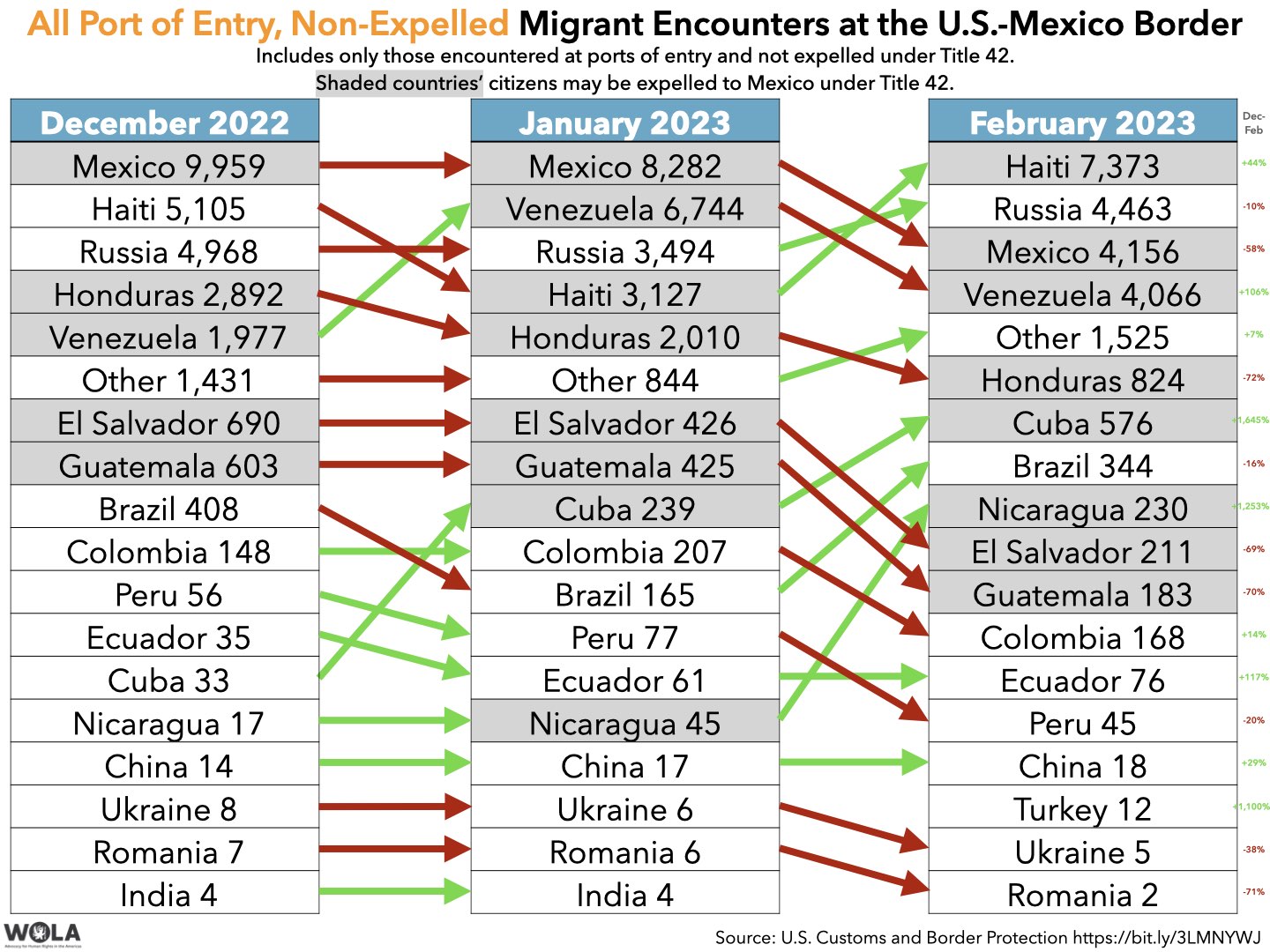

Venezuelan and Haitian citizens have arrived in increasing numbers at ports of entry, where most presumably have secured appointments to seek asylum. Since January 18, they have sought to do so using a feature in CBP’s smartphone app, CBP One.

“Since inception, over 40,000 individuals have scheduled an appointment via CBP One and the top nationalities who have done so are Venezuelan and Haitian,” noted CBP’s release announcing its February data. DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas recently told reporters that CBP was granting about 740 port-of-entry appointments to asylum seekers per day at 8 official border crossings.

While expanded barriers to asylum brought a striking short-term drop in migration from newly affected nationalities, the drop is unlikely to persist in the medium and long term. Border Patrol encountered more citizens of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras in February than in January, even though all four countries’ citizens have been subject to Title 42 expulsion into Mexico for nearly three years.

As noted in WOLA’s February 23 Border Update, the steep drop in encounters with Cuban migrants at the border has been echoed by a steep increase in encounters with Cuban migrants in south Florida, nearly all of whom took a route requiring them to navigate a maritime path across the Florida Straits. In February, nearly six times as many Cuban migrants arrived in Florida than arrived at the border. In December, it was more than the reverse: 34 Cubans arrived at the border for every Cuban who arrived in Florida.

In October the Biden administration made another pathway available to Venezuelans, and in January to Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans. If they have passports and U.S.-based sponsors, a combined total of up to 30,000 of these countries’ citizens may apply each month, from outside the United States, for two years of “humanitarian parole” in the United States. During February, CBP reported, “22,755 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (including immediate family members where applicable) were paroled into the country,” arriving at airports in the U.S. interior.

The Biden administration sent to Congress, on March 9, its funding request for the U.S. federal government’s 2024 budget. Online resources include the White House’s budget materials including a border and migration fact sheet, and the DHS Budget Justification including a 500-plus-page document for CBP.

DHS is several large agencies lashed together, among them CBP, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), FEMA, TSA, Coast Guard, and the Secret Service. Of the $60.4 billion in discretionary funding that the Biden administration is requesting for the whole department, nearly $25 billion would be for CBP and ICE, an $800 million increase over the 2023 levels.

According to the above-cited budget materials, the requested 2024 funds would:

The CBP budget request includes an interesting set of performance measures. Among them:

On the morning of Sunday, March 12 in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, Texas, several hundred mostly Venezuelan migrants “walked to the top of the Paso del Norte Bridge…to learn if a rumor about the border being temporarily opened was true,” El Paso Matters reported.

Migrants stranded in Ciudad Juárez by Title 42 expansion reported seeing rumors on social media ( example here) about CBP temporarily opening the border that day. Some rumors mentioned commemoration of a supposed “Migrants’ Day.”

As hundreds, or as many as 1,200, migrants—including many families with children—gathered in the middle of the Paso del Norte Bridge, CBP “hardened” its presence, putting up barricades and concertina wire, and arraying riot gear-clad officers along the borderline. Videos showed the crowd breaking through the toll booth’s crossing arm on the Mexican approach to the bridge, grabbing and shaking a coil of razor-sharp wire, and “attempt[ing] to hurl an orange, plastic barrier at the U.S. line,” Reuters reported, noting that CBP may have used pepper spray.

Upon learning that the border was not, in fact, open, the crowd withdrew. The bridge was closed for about five hours.

It is unclear how the “border opening” rumor originated on social media. While there is no proof that it came from someone seeking to generate images of chaos at the border, the incident showed how easy it would be for a bad actor to do so.

A clear cause is the lack of credible information available to migrants about the asylum process and new procedures. “The State Department needs to lean in and provide much more educational support south of us. Many of the migrants who are making the journey don’t understand immigration law,” Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who represents El Paso, told Border Report. “Migrants and advocates say the U.S. government has yet to clearly communicate the new policies to migrants,” the New York Times added on March 10.

On the Ciudad Juárez side, Mayor Cruz Pérez Cuéllar said, “We must say that our patience is running out” with the current population of mostly Venezuelan migrants. Municipal officials told Border Report that “migrant shelters are only 75 percent full and temporary jobs have been offered to those willing to work.”

The population currently stranded in Juárez right now, though, seems most focused on getting out of their current limbo. “Many of the families waiting in the sun under the Mexican and American flags told similar stories: an application that doesn’t work, shelters that have no space, police that shake them down for the little money they earn through informal labor each day,” El Paso Matters reported.

Many noted struggles with the CBP One app, now the only means of securing an appointment to apply for asylum at a port of entry. “Each day,” the Washington Post reported on May 11, “migrants awake before sunrise to search for a WiFi signal and try to get one of the 700 to 800 appointments available at eight entry points. Advocates estimate there are more than 100,000 people seeking entry. The appointments fill up within five minutes.” (See WOLA’s March 3, February 23, February 2, and January 20 Border Updates for more about CBP One.)

“Mexico does not have the infrastructure nor the political will to support Venezuelan refugees,” Fernando Garcia, executive director of the El Paso-based Border Network for Human Rights, told Border Report. “When they are in Mexico, they are alone.”