With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Border Updates will pause for the next two weeks as staff take vacation time. We will resume publication on June 23.

Very preliminary data indicate that, following a sharp fall in the days after the Title 42 policy’s end, numbers of U.S.-bound migrants have either flattened out or begun to increase again. Shelters are full in much of Mexico, meanwhile, where authorities continue to move large numbers of migrants toward the country’s southern border.

Asylum seekers who have been unable to secure “CBP One” appointments have begun lining up, for days at a time, at ports of entry in Nogales and Tijuana. The situation resembles CBP’s practice of “metering”—limiting asylum seekers’ access to ports of entry, and only allowing a small number per day to be processed—which a federal court declared to be illegal in 2020.

A few more details have emerged about the May 18 death of Raymond Mattia, a 58-year-old man shot multiple times by Border Patrol, while apparently unarmed, in the front yard of his house in the Tohono O’Odham Nation Reservation in Arizona. Family and friends have held protests and are pushing for accountability.

Three weeks have passed since the end of the pandemic-era Title 42 policy, which expelled migrants 2.8 million times from the U.S.-Mexico border over 38 months, regardless of asylum needs. Contrary to many predictions, the period following Title 42’s end saw a sharp drop in the number of migrants encountered at the border, from an early May high of over 10,000 per day to a mid-May low of less than 3,000 per day. (See WOLA’s May 19 Border Update.)

This drop is unlikely to persist for long, and early indications point to the number of migrant encounters already beginning to recover after touching their lowest level.

The quick drop after May 11, the last day of Title 42, likely owed to migrants adopting a “wait and see” stance amid uncertainty about the Biden administration’s new policies. On May 10, the departments of Homeland Security and Justice put in place a new administrative rule curtailing access to asylum, with a few exceptions, for all non-Mexican migrants (1) who were not first rejected for asylum in another country through which they passed, and (2) who did not make an appointment at a land port of entry (official border crossing) using CBP’s smartphone app, CBP One. Citizens of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela who meet both of those conditions may be deported into Mexico.

Lacking clarity about how this rule will play out, migrants who intend to seek asylum are crossing in much smaller numbers, at least for now. But very partial data seem to point to overall migration numbers ticking up slightly during the final days of May.

Along the route that U.S.-bound migrants take, most countries’ migration authorities share monthly data within two or three weeks after a month ends. As we await this data, we have partial clues about what post-May 11 migratory flows have looked like. The few available indicators, though, mostly uphold the idea of a reduction in migration followed by a gradual increase.

In the United States, Border Patrol Chief Raúl Ortiz’s Twitter account shares periodic updates with some of the agency’s enforcement statistics from previous days. During May, these show Border Patrol’s migrant apprehensions rising during the first third of the month, falling during the second third, and leveling off or even recovering a bit during the final third.

Ortiz’s “past week” tweets show a continuous decline since May 11: a per-day average of 7,850 apprehensions on May 6, 9,680 on May 12, 4,068 on May 19, and 3,149 on May 26. However, a “past 96 hours” tweet posted May 30 showed a daily average higher than what it was in Ortiz’s two previous updates: 3,396 apprehensions per day. That is 16 percent more than what the Chief had reported in a “past 72 hours” tweet 8 days earlier, on May 22 (2,917).

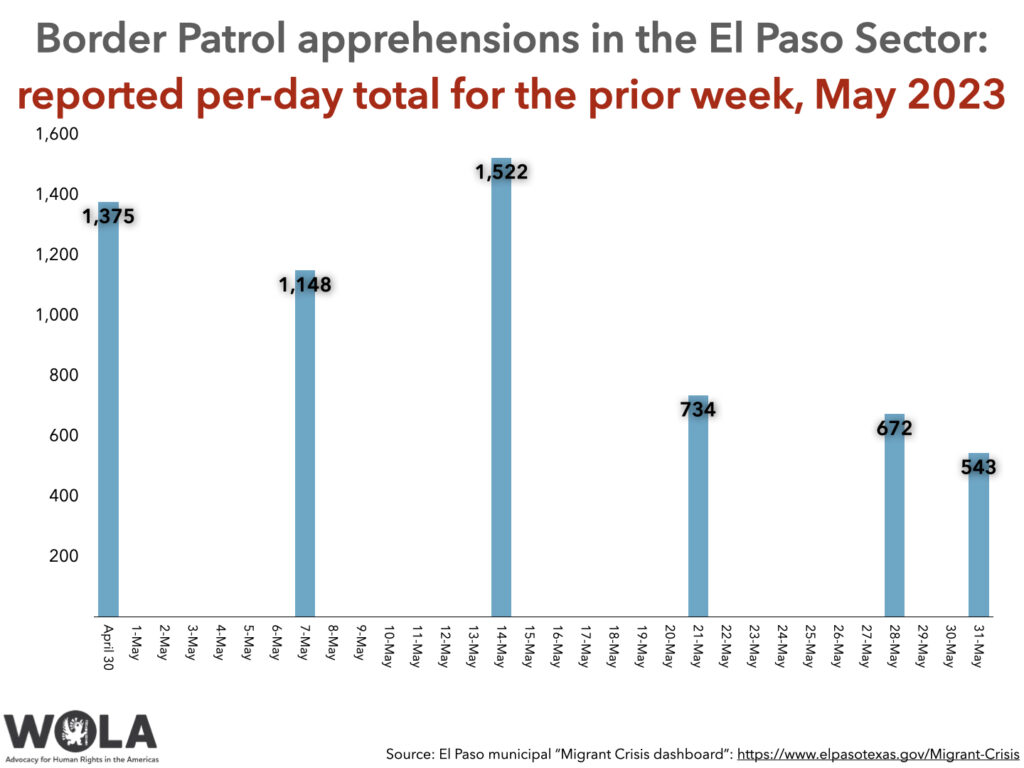

We have close to real-time data from Border Patrol’s El Paso Sector, thanks to a “dashboard” that El Paso, Texas’s municipal government posts to its website. That resource does not show any increase in migration during the latter days of May. It shows 7-day averages of 1,522 Border Patrol migrant apprehensions per day during the week ending May 14, 734 per day the week ending May 21, and 672 per day the week ending May 28. As of May 31, the 7-day average in El Paso had dropped to 543.

The leveling-off, or slight increase, indicated by Chief Ortiz’s tweets does not appear to be happening in El Paso.

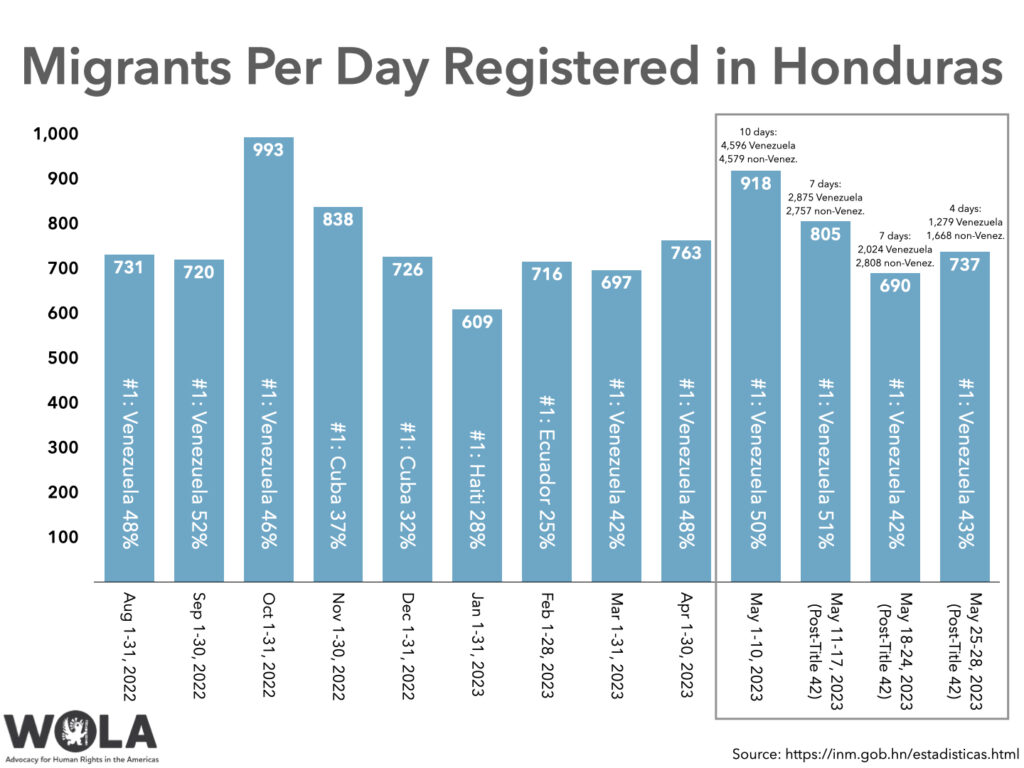

Honduras is the only country along the migration route that publicly shares data in something close to real time. Its early data do appear to point to some recent increase in migration transiting Honduras, after only a modest decline.

The number of migrants registering with Honduran authorities reached an average of 918 per day on May 1-10, the end of the Title 42 period. That fell to 805 per day the following week, and 690 the week after that. Interestingly, the drop from post-Title 42 week 1 to week 2 was entirely Venezuelan: the population of non-Venezuelan migrants actually increased.

Then, during the final four days that Honduras reports—May 25-28—the daily average increases once again, to 737 per day. Much of the increase is Venezuelan migration.

Honduras’ numbers are a reliable indicator of trends because a majority of migrants register with the government in order to obtain travel permits allowing them to transit the country. They register because in August 2022, Honduras declared an “amnesty” waiving a $240 fine to obtain permits. That amnesty, which must be renewed periodically, expired on May 31, and the Honduran Congress is to hold a special session on June 1 to consider its renewal, amid calls from UN agencies and humanitarian groups to approve it. (Last-minute update: the Honduran Congress extended the amnesty on the evening of June 1, to January 1, 2024.)

Further south, in Panama, authorities have yet to report on the number of migrants who passed in May through the treacherous Darién Gap jungles straddling Panama and Colombia. However, the director of the country’s migration authority said on May 31 that about 170,000 people had come through the Darién region so far this year. As Panama’s data show 127,687 migrants through April, that would indicate about 42,000 more in May—the largest monthly total this year, and third-largest ever in the Darién Gap. We don’t know, however, whether this migration flow reduced from early May to late May, and if it did, how steep the drop was and whether there has been any late-May recovery.

In Mexico we have only anecdotal data and rough estimates about some cities and shelters observing an increase in arrivals of migrants. The across-the-board trend, though, indicates that people are still coming to Mexico in large numbers.

Texas Rep. Henry Cuellar (D), who represents Laredo and western parts of the Rio Grande Valley, told Border Report that “Mexico has sent back over 30,000 migrants to its southern border to keep them away from the U.S. border” since May 11. At that southern border, in Tapachula, human rights groups denounced that Mexico’s migration authority (National Migration Institute, Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) has been expelling busloads of migrants into Guatemala—some of them families, many not Guatemalan—without informing them about where they were going, and without regard to any pending asylum applications they may have filed before Mexico’s refugee agency.

U.S. law states that anyone who fears return to their country may petition U.S. officials for asylum if they are on U.S. soil. Starting in 2016, and accelerating in 2018, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) began making it harder to reach U.S. soil at ports of entry (official border crossings), by posting officers on the borderline, including in the middle of bridges, to turn away people who lacked valid travel documents. Officers would only allow a certain, and small, number of asylum seekers to access the ports of entry each day.

In 2020, a federal district court ruled that this practice, known as “metering,” is not legal. That decision stands while the government appeals it. The situation was largely moot during the Title 42 period, when the Trump and Biden administrations reserved the right to deny asylum even to migrants on U.S. soil.

Now that Title 42 is no longer in place, though, a situation is arising at some ports of entry that resembles metering. Migrants who have not used (or have been unable to use) CBP’s smartphone app, “CBP One,” to book an appointment are waiting in line for days at the borderline, where CBP officers and, often, Mexico’s INM, are strictly limiting the number who can cross to ask for protection.

In Tijuana, Lindsay Toczylowski of ImmDef, a California-based immigration legal assistance nonprofit, posted a vivid thread of tweets on May 26 about the families her team was accompanying as they waited at the gates of the San Ysidro port of entry. CBP at first insisted that the families use the CBP One app (which makes about 300 appointments available at San Ysidro), then allowed them to present at the port of entry, with ImmDef’s advocacy, in a slow trickle: about one family every four hours. “Pretty surreal to be back in a position we often found ourselves during the Trump administration where the only way we could get CBP to accept asylum seekers was to have a Congressional Rep present to bear witness,” Toczylowski wrote. “Here we are again.”

By May 28, what the Tijuana investigative journalism magazine Zeta called “an improvised shelter” began forming at the port of entry’s gates. “In the camp there are migrants from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Colombia, Venezuela and Mexico.” The Biden administration’s new asylum “transit ban” does not even apply to citizens of Mexico, who are in the same country where they claim to face imminent danger, and did not pass through a third country to get to the United States.

“Local organizations also report that there has been a recent uptick in individuals who are returned to Tijuana after arriving at the port of entry with a CBP One appointment,” the University of Texas’s Strauss Center reported. Among them is a group of Haitian adults who had made a CBP One appointment: according to the Tijuana daily El Imparcial, “It turns out that when they got inside, nobody spoke their language…They were asked to sign a paper in English.” It turned out to be “a deportation paper,” and they were deported into Tijuana on May 25.

In Nogales, the Strauss Center reports, “As of May 23, 2023, there were more than 200 waiting asylum seekers, including at least 50 children.” CBP had processed about 100 people through the line—5 to 20 people per day—over the prior week. The Kino Border Initiative (KBI), a Nogales-based shelter and rights defense organization, has provided meals, “and reports hearing that people were limiting their water intake because of a lack of free, public bathrooms in the area.” KBI’s director, Joanna Williams, told local media that “Most of the families are sitting or sleeping on the ground, some of them have mattresses or are sleeping on cardboard.”

CBP denies that it is metering, which would violate the 2020 court order. “CBP is processing individuals who arrive at ports of entry and is not turning people away,” a spokesperson told Time, adding that the agency will make processing determinations “on a case-by-case basis.”

The CBP One app remains by far the principal way to secure an appointment to be processed for eventual asylum adjudication. But an International Organization for Migration (IOM) study in five Mexican cities, cited by Axios, found that half of migrants surveyed have been unable to schedule appointments using the app.

A frequent criticism of the app is its randomness: CBP One benefits those with the best smartphone skills and fastest Internet access more than those with the most urgent needs. “The app is a lottery system. It’s not prioritizing based on vulnerability or need for protection. It’s prioritizing based on who has the luck of the draw and…who has been waiting the longest to get a CBP One appointment,” the Migration Policy Institute’s Julia Gelatt told Time. “If access to asylum is going to be assigned at random,” the American Immigration Institute’s Dara Lind wrote at the New York Times, “the U.S. government had better make sure it’s doing everything possible—especially expanding staffing and physical space at ports—to maximize the number of slots available. And it must work toward evaluating everyone’s asylum claims on the merits.”

On May 31, DHS officials told CBS News that starting in June they plan to increase the daily border-wide number of CBP One appointments to 1,250 per day, up from about 740 in April and about 1,000 since May 11.

A few more details have emerged about the May 18 death of Raymond Mattia, a 58-year-old man shot multiple times by Border Patrol, while apparently unarmed, in the front yard of his house in the Tohono O’Odham Nation community of Menager’s Dam (also known as Ali Chuk), Arizona.

As noted in WOLA’s May 26 Border Update, a May 22 CBP statement reported that, after responding with tribal police to a call regarding shots fired in the area, three agents fired on Mattia after he threw an object near them, then “abruptly extended his right arm away from his body.”

Mattia’s family says that he had called Border Patrol after interacting with migrants on his property, which is not far from the border. Annette Mattia, the victim’s sister and neighbor, told Arizona Public Media that she saw “a bunch of Border Patrol vehicles drive into the yard.”

She grabbed her phone and called her brother. She told him Border Patrol were all over and asked what she should do.

Laughing it off, Raymond said, Just tell them to go away. Annette told him she didn’t want to talk to them as she watched the agents rush toward Raymond’s yard. He said he’d go out and talk to them.

“Next thing you know, I heard all the gunfire,” she says. “I didn’t know if it was him or not. I was shaking. I was scared. I was crying because I had that feeling that they did that to him.”

Border Patrol officials and their union, on the other hand, say that agents were responding to a “shots fired” call, and that Mattia “threw a machete at the officers that landed a few feet away.”

CBP’s Office of Public Responsibility, along with the Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department and the FBI, are reviewing body-worn camera footage of the incident. At least 10 of the Border Patrol agents at the scene, including the 3 who opened fire, were wearing body-worn cameras and had them activated, according to CBP.

Annette Mattia told Arizona Public Media that Raymond’s body remained in his front yard for seven hours until the medical examiner arrived. “We just got to say our goodbyes in a bodybag,” she said.

People, including some of Mattia’s relatives, gathered to protest outside of Tucson Sector Border Patrol headquarters and the Ajo Border Patrol station on May 27.

“My uncle didn’t deserve to die like this,” Yvonne Nevarez, Mattia’s niece, told the Arizona Republic at a protest. “I know he would have been doing this if it happened to any of us.” Ophelia Rivas, a friend of the victim, added that Mattia “was on the community council of the village and would often speak up about Border Patrol abuses.” Rivas added, “This aggression and racist attitudes of the Border Patrol have gone unchecked for so many years. We’re just here to say that we’ve had enough of this. We want justice for Ray.”

Raymond Mattia died the day after he turned 58. “His daughter was crying remembering the cake she had made that she never got to give him,” Arizona Public Media reported.

The family has established a GoFundMe to help cover legal fees and traveling expenses.