Contents

- A new accord

- Referendum versus constitutional convention

- Transitional justice

- Colombian Politics

- Next topic: drug policy

- U.S. policy toward the dialogues

- The ELN remains on the sidelines

- Victims

A new accord

Colombia’s peace talks took a large step forward on November 6th. In Havana, Cuba, negotiators from the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, Colombia’s largest guerrilla group) announced that they had reached agreement on reforms to ease political participation for opposition movements, including any post-conflict party incorporated by demobilized FARC members. This was the second of six points on the negotiating agenda [PDF] agreed in August 2012.

Between May 26th—the date that they announced an accord on the first agenda item (land and rural development)—and November 6th, negotiators met in Havana for seven rounds encompassing about 65 days of talks. They extended their latest negotiating round, their 16th, an extra five days to achieve this new agreement. It moves the talks’ agenda forward, after five months that saw growing impatience in Colombian public opinion. It provides the process with a badly needed boost of momentum, just as campaigning gets underway for Colombia’s March 2014 legislative and May 2014 presidential elections.

With the second agenda item concluded, the topics remaining to be agreed are “ending the conflict” (demobilization and transitional justice); “solution to the problem of illicit drugs”; conflict victims; and “implementation, verification, and legalization of accords.” None of these are easy, though transitional justice—how to bring the worst human rights violators to justice—promises to be most challenging. The negotiators have decided to skip that agenda item for now, and will begin discussing drug policy when they reconvene in Havana on November 28th.

The text of the “rural development” and “political participation” agreements is secret for now, and under the principle of “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed,” the negotiators may still revise them before they sign a final accord. Still, the negotiators’ joint November 6 declaration gave a reasonably detailed overview of what was agreed. Points include the following.

- A multi-party commission to seek input and make recommendations for a new “Opposition Statute.” This law will spell out guarantees for peaceful political opposition movements, which have often met violent ends in Colombia, and a series of guarantees for channeling citizen demands and protests.

- Measures to improve social and political movements’ access to institutional, regional, and community media.

- National and local “Councils for Reconciliation and Coexistence” to implement guarantees, and a plan for citizen oversight and transparency of public policy.

- Changes to ease the formation of political parties.

- Improvements to transparency over elections.

- The creation of Temporary Special Peace Districts encompassing “zones especially affected by the conflict and government abandonment.” These districts will elect their own legislators to Colombia’s House of Representatives.

- A security system to protect opposition candidates, “especially those of the new movement that may emerge from the FARC-EP to legal political activity.”

- The joint declaration notes that implementing the peace accord “will imply the relinquishing of arms and the prohibition of violence as a method of political action.”

- “A gender focus assuring women’s participation.”

The technical, detailed nature of these agreed measures is itself an important reason for optimism about the peace process. It indicates a degree of discipline and seriousness that the government and FARC frankly never reached during three previous negotiation attempts since 1982.

Probably the most controversial of these elements are the special temporary congressional districts for historically conflictive areas. These appear designed to give demobilized FARC candidates an advantage in zones where the group has long had de facto political influence or control. Negotiatiors have not yet determined their number and duration.

This falls short of the FARC’s original demands for a number of guaranteed temporary congressional seats or a new chamber of Congress with equal numbers of representatives from each department (province). Still, it is controversial within mainstream Colombian public opinion, where polls consistently show a large majority of Colombians opposed to the prospect of former FARC members serving in the national legislature. Unless the pace of the talks picks up remarkably, though, this accord will have no effect on the March 2014 congressional elections. The temporary congressional districts benefiting former FARC candidates would likely not exist until Colombia’s next legislative elections, in 2018.

|

|

In this striking image from Colombia’s Semana magazine, FARC Secretariat member Iván Márquez (right) walks by former Colombian Armed Forces chief Gen. Jorge Mora on November 6th in Havana.

|

Five months may seem like a long time to have achieved agreement on these rather technical points. The Colombian newsweekly Semana called them “a letter of good intentions that, in general terms, coincide with rights already guaranteed in the constitution.” The delay in reaching this second agreement appears to owe at least as much to three issues that were only partially or tangentially relevant to the “political participation” agenda item:

- The FARC’s demand for a constitutional convention, at which elected representatives (presum

ably including automatic FARC seats) would rewrite Colombia’s 1991 constitution to cement peace accord commitments in place. - Increasing concerns—in the FARC but also to some extent within Colombia’s armed forces—about the need to apply justice to the worst human rights violators.

- The proximity of legislative and presidential elections, and uncertainty that President Juan Manuel Santos—or any president who favors the peace talks—might be in power after August 2014.

Referendum versus constitutional convention

Though it is more appropriate to the sixth round of the negotiating agenda than to the second, FARC negotiators made clear in mid-June, and on many other occasions, that they wanted a constitutional convention to enshrine an eventual peace accord in permanent law. “For more than 30 years the FARC have awaited the convening of a National Constituent Assembly to find a true solution to the conflict with the people’s decisive participation,” read a June 11 FARC statement.

There are two main reasons why the guerrillas want to rewrite the constitution, instead of simply giving the accords legal status through a public referendum, the Colombian government’s preferred option. First, this was the outcome of Colombia’s last successful peace process with a leftist guerrilla group. After it concluded negotiations in 1990, the M-19 guerrillas—a far smaller group than the FARC is today—won more than a quarter of seats in the constituent assembly that redrafted Colombia’s 1886 constitution into the more progressive 1991 document that is now in force. For FARC leaders, getting less than that status is hard to accept.

|

|

Demobilized M-19 guerrilla leader Antonio Navarro Wolff, center, was one of three co-presidents of the 1990-91 constitutional convention that rewrote Colombia’s constitution.

|

A perhaps more compelling reason for guerrilla leaders’ constitutional convention demand is their concern that approving a peace accord through regular law is not strong enough. Years from now, they worry, a future government—one perhaps made up of the peace talks’ current opponents—could change course and capriciously change the law to undo the Colombian government’s peace accord commitments. These changes could even apply to imprisonment or extradition of demobilized guerrillas. By locking these commitments into Colombia’s constitution, the guerrillas believe it would be harder for a future government to take such steps.

The government resists this demand, arguing that approval in a referendum is a strong enough assurance of peace accord commitments’ permanence. Government officials like chief negotiator Humberto de la Calle also ask why the negotiators would be wasting time reaching a peace accord based on an agreed agenda, if a future constitutional convention could simply end up approving an entirely different set of reforms. Other observers, noting the FARC’s low standing in polls and the popularity of peace process opponents like former President Álvaro Uribe, question why the FARC would risk seeing Colombians elect a right-wing majority. The resulting constitutional convention could do away with much of what gets agreed at the negotiating table.

The issue remains unresolved, but was set aside for the time being in order to complete items that fit more strictly within the second agenda point. It flared up most seriously in late August, though, when the Santos administration introduced legislation that might make it possible to schedule a referendum concurrent with the March or May 2014 elections.

As they had not agreed to a referendum, the FARC announced a “pause” in talks on August 23rd. Guerrilla negotiators got up from the 13th round of negotiations for three days in order to “study” the government’s proposed legislation. As the bill does not actually schedule a referendum—it just makes one possible, as Colombian law normally prohibits referenda concurrent with other elections—the FARC quickly returned to the table.

The episode, though, was the only interruption in the talks’ schedule so far. As of mid-November, versions of the referendum enabling bill have passed both Colombia’s House and Senate.

Transitional justice

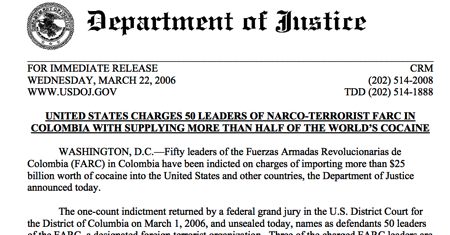

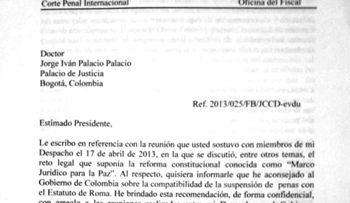

The talks’ agenda has yet to reach “ending the conflict,” the topic that includes the thorny question of how to bring the most serious guerrilla and government human rights violators to justice. Colombia’s is the world’s first peace negotiation involving a signatory of the 2002 Rome Statute, making it a party to the International Criminal Court (ICC, based in The Hague, The Netherlands). As a result, Colombia cannot amnesty or suspend sentences for those who committed war crimes or crimes against humanity, as happened in peace processes in El Salvador, Guatemala, or South Africa.

In two letters in July and August, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda made clear that if Colombia were to negotiate a peace deal that included amnesty for serious human rights violations, the international court would be compelled to act on its own to prosecute ex-guerrillas or members of the security forces. The same would likely occur, she warned, if Colombia were to adopt an arrangement that included trials but no punishments, such as suspended sentences in exchange for full confessions. “The decision to suspend a prison sentence would suggest that the proposed judicial process has the purpose of removing the accused from his criminal responsibility,” warns Bensouda’s July 26th letter to Colombia’s Constitutional Court.

|

|

This July 26th letter (PDF) from ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has probably chilled FARC leaders’ expectations of avoiding punishment for human rights crimes.

|

This places Colombia in a quandary, as it will be difficult to convince top guerrilla leaders to turn in their weapons only to go to prison (or some alternative penal arrangement). FARC leaders have already expressed outrage at this prospect: “We haven’t fought

our entire lives for peace with social justice and the dignity of Colombians only to end up locked up in the victimizers’ jails,” lead FARC negotiator Iván Márquez said in April. Similarly, Colombia’s military—which might be expecting gratitude for weakening the FARC enough to make negotiations possible—would likely resist a series of deeply embarrassing trials for participation in crimes like thousands of extrajudicial executions and collaboration with paramilitaries.

Colombia’s “Legal Framework for Peace [PDF],” a constitutional reform passed in June 2012, sets the boundaries for whatever transitional justice arrangement emerges from the talks. It requires any such arrangement to include a truth commission, and criminal investigations of “those maximally responsible” for “crimes against humanity, genocide, or systematically committed war crimes.” The Legal Framework holds open the possibility that an eventual law could include suspended sentences for human rights violators, and perhaps even amnesty for those who committed crimes deemed less serious—even though either option might trigger action from the ICC. On August 28th, by a 7-to-2 vote, Colombia’s Constitutional Court upheld the Legal Framework, with the possibility for suspended sentences and amnesty for “less serious crimes” intact.

On October 23rd the same high court, citing procedural flaws, struck down a different law regarding human rights crimes. A constitutional amendment passed in December 2012, and an enabling law passed in June 2013, gave the military court system broader jurisdiction over human rights cases. Both specified seven types of abuse that must go to civilian justice, leaving the rest to the military system, which has a long record of failing to punish members of the armed forces accused of rights violations.

Non-governmental human rights defenders roundly criticized this reform, arguing that it would make it harder to prosecute abuses, and that it might even lead to some cases of “false positives”—military murders of civilians disguised as armed-group members killed in combat—being transferred to the lenient military justice system. These concerns disappeared with the Constitutional Court’s revocation of both the constitutional amendment and the enabling law. Cases of military human rights abuse must once again go to civilian courts, where the maximum penalty is 40 years’ imprisonment. While a positive step for human rights, the court decision raised concerns that the powerful armed forces’ support for the peace process could decline.

If the conflict ends, it is also possible that soldiers could be tried by whatever transitional justice mechanism emerges from the “Legal Framework for Peace.” The Legal Framework makes it possible for a future law to allow both soldiers and guerrillas to serve lighter sentences in exchange for confessions, reparations to victims, and similar measures.

How this might apply to soldiers must be decided by that future law. How it might apply to guerrillas will be the subject of a future phase of the government-FARC negotiations. FARC leaders’ concerns about imprisonment, though, may already be slowing the pace of talks. The letters from the ICC prosecutor, speculated Mauricio Vargas, a columnist for the Colombian daily El Tiempo, likely inspired the FARC to “put on the brakes.”

It is difficult to predict the sort of transitional justice framework that might emerge from the peace talks. A likely outcome, though, might amnesty all but the “most serious” human rights violations, as long as those receiving amnesty confess to their crimes and make some amends to victims. (Even this would go beyond the mid-2000s demobilization of Colombia’s pro-government paramilitary groups, which amnestied, without confessions, all but about 4,000 of these groups’ members.) Those accused of the most serious crimes, a group that could include most top FARC leaders, would have to serve some sort of sentence that denies them liberty for a period of time. The International Crisis Group, in an August report, suggests, in lieu of existing prisons, “alternative facilities placing meaningful restrictions on liberty… or special areas… in which FARC members could live and work under strict curfews and probation-like restrictions.”

It is not impossible to imagine FARC leaders going along with such an arrangement. If it comes with a parallel justice effort for military human rights violators, it might be seen as less of a humiliating surrender. And if the alternative penal arrangement allows ex-guerrilla leaders to communicate with the outside world and to help organize the FARC’s future as a political movement, several years in a facility guarded by police—instead of on the streets of Colombia where they would face constant threat from would-be assassins—could ease their transition to civil life.

Colombian politics

While discussions of referenda and transitional justice slowed the pace, the talks were not occurring in a vacuum. Colombia’s political environment has heated up as well, with March 2014 legislative and May 2014 presidential elections fast approaching.

The past several months saw an increase in protests, as small producers took to the nation’s roads to press for mostly economic demands. Coffee growers, hit by a drop in global prices, protested in February and March, and won subsidies. Farmers, including coca growers, blocked roads in June and July in the northeastern region of Catatumbo to press for greater government investment and an end to aerial fumigation of coca crops; the FARC issued a statement in support. On August 19, farmers in several parts of the country, many of them blaming Colombia’s free trade agreements for their economic woes, marched and blocked roads in the largest national protest yet.

The Santos administration’s response to the protests appeared confused. The President sent high officials to negotiate with protesters, and likely wished to demonstrate to guerrilla negotiators that space for peaceful dissent exists in Colombia. At the same time, farmers who blocked roads often met with a very violent response from police, and numerous people were injured on both sides. Some government officials alleged that protesters were organized or encouraged by guerrillas trying to show political influence and exert pressure at the negotiating table. As far as could be discerned, though, the vast majority of protesters had concrete demands and had no relation to guerrilla groups.

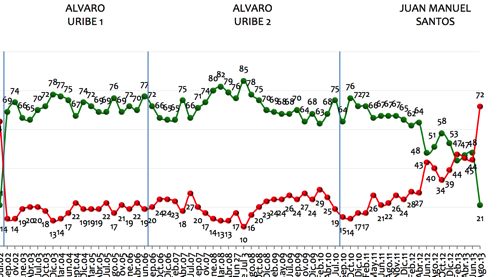

President Santos’s incoherent reaction—at one point in August, amid a wave of road blockages, he said “the so-called farmer strike doesn’t exist”—cost him heavily in public opinion, especially after a day of solidarity protests in Bogotá on August 29th partially shut down the city and witnessed widespread acts of vandalism. A Gallup poll taken at the time [PDF] measured President Santos’s approval rating at a dismal 21 percent, down from 48 percent two months earlier. It was the largest two-month drop Gallup had ever measured in Colombia.

The same late-August poll found a majority—though at 62 percent not an overwhelming majority—backing the peace talks with the FARC. However, 60 percent believed that the process will not succeed. Other polls show large majorities opposing the idea of former guerrillas participating in politics, a likely outcome of the negotiations.

While President Santos’s approval rating has recovered somewhat in subsequent polls, his shaky performance has fed uncertainty about his re-election in May. This in turn feeds uncertainty about the future of the FARC-government negotiations after the May 2014 elections.

Former President Álvaro Uribe, who preceded Santos and is now his most vocal political opponent, remains loudly opposed to the peace talks. Uribe, whose favorability rating in an early November Gallup poll was a solid 73 percent, is constitutionally prohibited from running for a third term, but has announced his intention to run for Senate in March. His political party, the “Pure Democratic Center,” nominated a presidential candidate in October. “Peace is not in Havana. The national agenda isn’t up for negotiation with the FARC,” said candidate Oscar Iván Zuluaga, who was Uribe’s finance minister, in his nomination speech.

On November 12th, the peace process was thrown into a minor crisis when Defense Minister Juan Carlos Pinzón and Police Chief Rodolfo Palomino announced the discovery of an alleged plot, by an elite FARC column active in southern Colombia, to kill the former president. If carried out, “an attempt of this kind would destroy the viability of the peace process,” said chief government negotiator de la Calle. Further details about the alleged plot have not emerged, including how serious it was, how long ago it was hatched, and whether top guerrilla leadership knew about it. Colombian media speculated that top FARC leaders could be losing control of the unit accused of plotting to kill Uribe, the Teófilo Forero Mobile Column.

Right now, Santos leads Zuluaga (who has little name recognition) and all other possible candidates by a comfortable margin in polling for the May 2014 vote. However, polls also show that most Colombians don’t want to see Santos re-elected. Campaigning is getting underway as of November, as candidates declare their intentions, and the peace process has become a central—perhaps the determining—factor in deciding whether Santos will be re-elected. Perceptions that the talks are going well help the President’s electoral prospects. Perceptions that they are going badly will help his opponents, particularly Zuluaga and the uribistas.

This puts FARC leaders in an odd position. If they want the peace process to continue, they need to see Santos re-elected, as he is the only currently viable candidate who promises to keep the process going. (In other words, they must back the politician who oversaw the military operation that killed their leader in 2011.) This means the FARC must feed perceptions that the talks are going well, which in turn means advancing along the negotiating agenda.

These pressures to advance came to a head in early November, as the negotiating teams extended the 16th round of talks for several days so that they could announce an accord on the second agenda item. They will continue to mount as the 2014 campaign intensifies, especially if it becomes evident that the peace talks’ fortune will make or break the President’s re-election.

Next topic: drug policy

When the negotiators meet again in Havana on November 18th, they will skip the transitional justice agenda topic for now and move on to the fourth item: drug policy. According to the agreed negotiating agenda, “drug policy” encompasses some broad sub-topics: “crop substitution programs,” “consumption-prevention and public health programs,” and “solution to drug production and trade.”

This may be one of the easier agenda items for the two sides to manage, as both agree on a need to reform drug policy. Even though the FARC gets much of its funding from the drug trade, its leaders have indicated a post-conflict willingness to lead coca eradication in their areas of influence if it came with development assistance. For his part, President Santos has made occasional comments about the need to rethink the “drug war” approach, most recently in his September speech before the UN General Assembly, and has appointed drug-policy critics to the UN International Narcotics Control Board and to the Colombian government’s own Presidential Advisory Commission on Drug Policy.

The head of that latter commission, University of the Andes economist Daniel Mejía, has published work finding the aerial spraying of coca with herbicides—a cornerstone of Colombia’s U.S.-backed anti-drug effort since 1994—to be i

neffective and even harmful to human health. Allegations of damage to health, the environment, and legal crops are widespread in regions of rural Colombia where Colombian police and U.S.-supported contractors seek to kill coca crops by fumigating with the herbicide glyphosate.

Though the U.S. contribution has declined as Washington has handed management over to Bogotá, the fumigation program is still backed by at least US$40.8 million from the United States each year. As a result, Colombia reported [PDF] spraying 100,549 hectares (248,462 acres) of coca in 2012.

Nonetheless, the “drug policy” agenda point could bring an agreement to end fumigation. Coca is not sprayed with herbicides in Peru and Bolivia: it is eradicated by hand. Colombia adopted spraying chiefly because the presence of guerrillas made manual eradication too unsafe. (However, Colombia eradicated more coca manually in 2012 than did Peru and Bolivia combined.) If the guerrilla presence disappears, then presumably the danger to manual eradicators disappears—and in fact, a “drug policy” agreement might end up committing former FARC members to helping eradicate coca in areas where they have been dominant. “If we manage to get the guerrillas, once they’ve demobilized, to change sides and become an ally of the State to curb drug trafficking and end illegal crops, just imagine what it would entail,” said President Santos in his September UN speech.

Ending the fumigation program was one of the most frequently voiced recommendations at a September 24-26 forum in Bogotá organized, at the request of the negotiating parties, to collect Colombian civil society proposals on the “drug policy” agenda item. Of the 1,200 participants, most of them from rural zones throughout the country, many called for a halt to the spraying and proposed some variation of manual eradication in a larger context of bringing governance, basic services, and development assistance into the historically ungoverned areas where drug production thrives.

The negotiators’ discussion of drug policy may also cover proposals to decriminalize or regulate consumption or even production of certain drugs. The FARC’s maximum leader, Timoleón Jiménez or “Timochenko,” released a statement on November 12, citing free market economist Milton Friedman, calling for “contemplating legalization” in the drug-policy agenda discussion. (“Our satisfaction for a Colombia without coca will be enormous,” the statement also reads.) While President Santos has expressed sympathy for some degree of decriminalization, it is not clear whether his government would go much farther than existing Colombian law, in which high courts have upheld permitting the possession of a “personal dose” of some drugs.

Nearly all FARC leaders of any significance are wanted by U.S. courts to face drug trafficking charges. The “drug policy” discussion is likely to include a FARC demand for guarantees that former guerrillas who abide by the peace accords’ terms will not be extradited. The Colombian government is likely to grant these guarantees, since FARC leaders clearly won’t demobilize if doing so means ending up in a U.S. prison. The Obama administration cannot rescind extradition requests issued by the justice system. The State Department can decide, however, whether refusals to extradite former FARC leaders have any impact on U.S. relations with Colombia.

Drug policy is the negotiating agenda topic that most closely affects U.S. interests and aid programs in Colombia. The result of this segment of the negotiations could come quickly, and it might require some changes to the way the United States and Colombia have cooperated on anti-drug strategy. These changes might be uncomfortable to some U.S. government agencies that, for instance, might prefer to maintain the fumigation program and to enjoy very high compliance with extradition requests. A peaceful outcome will depend on a flexible response from the Obama administration, which must maintain its support for the negotiations even if it finds the drug policy accord to be less than optimal.

U.S. policy toward the dialogues

The administration’s support for the talks has so far been steady, though official public expressions of U.S. backing are rather infrequent. In the past five months, the only significant example was Secretary of State John Kerry’s August 13 visit to Bogotá, when he made some of the clearest statements yet of U.S. intent to reorient assistance programs to a post-conflict Colombia.

Officials have said little else, though, a silence caused in part by the lack of a U.S. ambassador to Colombia since Peter Michael McKinley’s tour ended at the end of August. The U.S. Senate has not yet scheduled a hearing to consider the nomination of his successor, career diplomat Kevin Whitaker. Notably, the November 6th accord on political participation did not merit a public congratulatory response from any U.S. government official. The only statement from official Washington was a note of congratulation from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Massachusetts).

On December 3, President Santos is to visit Washington and meet with President Obama. At the meeting, according to White House Spokesman Jay Carney, the U.S. President “will express his support for Santos’ efforts to pursue peace.”

Secretary of State Kerry did issue a statement on October 27th, the day the FARC freed U.S. citizen Kevin Scott Sutay, an Afghanistan war veteran whom guerrillas captured in June after he embarked on a solo journey through southern Colombia’s jungles. The FARC announced its intent to release Sutay to a committee including the ICRC and leftist Colombian politician Piedad Córdoba. President Santos had refused these terms on the ground

s that they would create a “media show.” U.S. civil rights leader Jesse Jackson offered to intercede in September, but President Santos turned him down.

In the end, the FARC—which issued an early October article indicating some fondness for their captive—released Sutay to a delegation of representatives of the ICRC and the two guarantor countries of the peace process, Cuba and Norway. In his statement, Secretary Kerry thanked President Santos, Jesse Jackson, the ICRC, Norway, and Cuba for their assistance in securing Sutay’s release. It was the first time in memory that an official U.S. statement had thanked the Cuban government for anything.

The ELN remains on the sidelines

On September 9th Colombia’s vice president, Angelino Garzón, said that talks with Colombia’s second guerrilla group, the roughly 1,500-strong, 49-year-old National Liberation Army (ELN), would start “in the coming days.” This prediction proved to be too optimistic. While secret contacts about getting dialogues started probably continue, as of mid-November there has been no official launch of ELN-government talks.

The government and the ELN appeared to be closest around August 27th, when the guerrilla group released a Canadian citizen whom it had been holding hostage since January. The Santos administration had made clear that it would not negotiate with any group currently holding hostages or kidnap victims. The ELN replied that it would not release geologist Jernoc Wobert until his company, Braeval Mining, renounced gold-mining titles in the department (province) of Bolívar that the guerrillas alleged were obtained without communities’ consent. In July, Braeval announced that it would pull out of the mining project, and the ELN released Wobert soon afterward to the ICRC.

|

|

Jernoc Wobert regains his freedom on August 27th.

|

With this obstacle to the launch of talks cleared away, expectations of an imminent “peace table” with the ELN grew. “The government is ready to start dialogues with the ELN,” President Santos said on August 28, the day after Wobert’s release. Media outlets even speculated about the challenges of holding separate or combined negotiations with the FARC, whether the government would agree to discuss extractive industries—a central issue for the ELN—and where talks might take place (with Uruguay seen as a main contender).

These dialogues have not yet materialized, though. On October 27th, ELN Central Command member Antonio García told Colombia’s El Tiempo that the government “lacks political will” to start dialogues and criticized the FARC talks’ agenda as “very limited.” Still, the ELN have issued warily supportive comments on the FARC negotiation process. Most recently, the group noted the FARC-government agreement on political participation but questioned whether the government would actually deliver on its commitments.

Victims

The launch of talks with the ELN is probably less likely during Colombia’s politically charged election season, which runs more or less from now until next May (or June if a presidential runoff is needed). President Santos has declared that he will not pause the process during the campaign. The next weeks or months will see negotiation of the drug policy agenda item.

If the sides reach agreement on drug policy, the remaining substantive issues to be negotiated are “ending the conflict” (demobilization and transitional justice) and “victims.” Should the parties decide to postpone the transitional justice topic further, the victims issue will arise—and it promises to be complicated.

Two parties, each of which has victimized thousands of people over the course of the conflict, are to hold a closed-door discussion of how to attend to victims. This is problematic, especially when neither side has properly recognized that it has a responsibility to its victims—or even that significant numbers of victims exist.

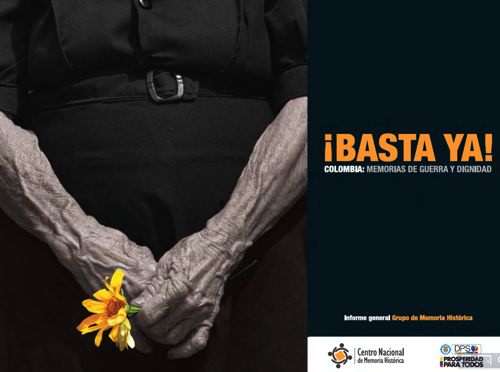

On July 24th, Colombia’s Center for Historical Memory struck an important blow on victims’ behalf. The Center is an autonomous government body first established by the “Justice and Peace Law” that governed paramilitary groups’ mid-2000s demobilization. Its team of scholars and investigators released its final report, based on about five years of research, at a Bogotá event keynoted by President Santos. The report, Enough Already – Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity, found that the armed conflict had killed 218,094 Colombians since 1958, displaced up to 5.7 million since 1985, disappeared 25,007 since 1985, and involved 27,023 kidnappings since 1970.

In its 400 pages, Enough Already sought to ascribe shares of responsibility for atrocities. It found both government and guerrillas (as well as paramilitaries) all responsible for significant shares of non-combatant civilians victimized in the conflict. Guerrillas committed about 20 percent of massacres and 23 percent of selective killings for which a responsible party could be identified, while government forces committed 9 percent of massacres and 14 percent of selective killings (and likely aided or abetted many of those killed by paramilitaries, who carried out a far larger share of both). Guerrillas committed the majority of kidnappings, use of illegal landmines, and recruitment of minors. The report also sought to narrate the conflict from the perspective of the many victims whom the researchers interviewed, in order to place them at the center of the account and assert both their dignity and the combatants’ need to provide truth, restitution, and reparations.

“There is an issue here which is another of those ‘uncomfortable’ truths that are also being faced,” said President Santos at the launch of Enough Already.

“I refer to cases of state agencies’ collusion with illegal armed groups, and the security forces’ acts of omission at some stages of the internal armed conflict, which the Center for Historical Memory’s reports also reflect. The state must investigate and punish this conduct in order to comply with the victims’ rights to truth and justice.”

This modest statement was one of the clearest recognitions of government responsibility for victims that a Colombian leader has ever made. And it was partially contradicted by Defense Minister Juan Carlos Pinzón, who criticized the Center for Historical Memory’s report for measuring the armed forces by the same standard as guerrillas and paramilitary groups. “We cannot accept the building of a historical memory based on the hypotheses of radical sectors,” Pinzón said.

The report’s release also encouraged FARC leaders to begin reflecting on their large responsibility to their victims. Earlier in the peace process, FARC leaders had angered Colombians with statements rejecting the idea that the guerrillas had victims, and arguing that the FARC themselves were victims. (In October, when asked by a Spanish reporter in Oslo whether the FARC would ask forgiveness of its victims, FARC negotiator Jesús Santrich responded by laughingly singing the refrain of a Cuban song from the 1940s: “Quizás, Quizás, Quizás“—the word meaning “perhaps.”)

By August, the guerrillas’ tone had begun to soften a bit. “Without a doubt there has also been cruelty and pain provoked by our forces,” read an August 20 FARC statement. “We must all recognize the need to take on the issue of victims, their identity and reparation with total loyalty to the cause of peace and reconciliation.” Asked in November how the FARC might provide reparations to its victims, FARC negotiator and Secretariat member Pablo Catatumbo responded, “I don’t have the formula. That is an issue that we will take up at the table at the proper moment. The only thing I want to say to you is that we are neither insensitive nor cynical about that.”

Statements like these are baby steps, given the gravity of the horrors documented by the Center for Historical Memory. Neither side has yet expressed genuine contrition for the tragedies it has caused, or a clear will to make amends. That remains for the upcoming discussion of the “victims” agenda item. At that point, the credibility of the process will require both the FARC and the government to express far less denial and far more respect for the dignity of their many victims.