For over 25 years, the Washington Office on Latin America has closely tracked Colombia’s armed conflict and efforts to end it. Here is our assessment of the current moment.

SEE ALSO: What Colombia’s Truth Commission Can and Can’t Do

How would a peace accord benefit U.S. interests in Colombia?

In the 12 years between the launch of “Plan Colombia” (2000) and the relaunch of talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas (2012), Colombia tripled its defense budget and increased its armed forces by about 75 percent. A long offensive decreased the FARC’s size by about two-thirds. Today, this means that the FARC still has about 7,000 members and 15,000 support personnel. Though the FARC has no hope of taking power by force, the past 12 years’ rate of reduction promises years of continued conflict.

After 51 years of fighting, negotiation offers a quicker way to end the FARC’s status as a cause of violence and drug production. A peace accord would dissolve a group on the U.S. list of foreign terrorist organizations, as thousands of its members move into legality. This would ease efforts to reduce production and transshipment of U.S.-bound illegal drugs. And it would offer an opportunity for improved governance over historically lawless territories that provide safe haven to terror groups and traffickers.

Is a peace accord likely?

Yes, but getting there will be slow. Formal negotiations began two and a half years ago, and could easily take another year. Nonetheless, negotiators at the table are working in a disciplined way with international accompaniment, respecting the ground rules and generating hundreds of pages of proposals and dozens of pages of draft accords.

Negotiators have signed preliminary accords on rural development, political participation for the opposition, reforms to drug policy, and a truth commission. They have taken some steps toward de-escalating the conflict: the FARC is cooperating with the government on initial de-mining projects, and has agreed to turn over any minors in its ranks under the age of 15.

Negotiators announce agreement on a Truth Commission in June.

Still, some of the most difficult questions remain unresolved. Negotiators must find a way to hold human rights abusers accountable while also persuading them to disarm. They still must come to agreement on reparations to victims, the nature of combatants’ disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration, and the method of ratifying a final agreement.

The negotiations are going on without a ceasefire, amid frequently intense combat. This is a deliberate choice of the Colombian government, which is concerned that the FARC might use a ceasefire to regroup and reinforce itself. President Juan Manuel Santos insists that a bilateral cease-fire must wait until the end of the process. In the meantime, acts of violence undermine public support for the dialogues, and affect the climate at the negotiating table.

Are the talks in a rough patch?

Yes. The FARC had declared a unilateral cease-fire effective December 20, 2014, which brought an approximately 85 percent reduction in guerrilla offensive actions (though guerrilla “fundraising” activities, like extortion and narcotrafficking, continued). The ceasefire was not reciprocal: though the government halted aerial bombings of FARC targets in March, the guerrillas complained of frequent military ground attacks.

On April 15, FARC fighters attacked a military column encamped in a rural town in southwestern Colombia, killing 11 soldiers. The guerrillas refused to acknowledge any wrongdoing, and the government responded by resuming aerial bombings, including three raids in May that killed over 40 FARC members. The FARC revoked its cease-fire on May 22, and has since carried out a steady campaign of attacks on civilian economic infrastructure. Attacks on oil pipelines and power lines are causing environmental damage and blackouts.

The aftermath of the April 15 FARC attack.

What does public opinion say?

The guerrilla offensive has dangerously drained support for the talks. In late February, during the guerrillas’ unilateral cease-fire, Colombia’s bimonthly Gallup poll found 72 percent of respondents supporting the government’s decision to negotiate with the FARC. For only the second time since the talks started, Gallup found a majority—53 percent—optimistic that an accord might be reached. Two months later, those numbers fell to 57 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

Would a ceasefire help?

Some analysts contend that the guerrillas are deliberately seeking to anger Colombians, in the belief that President Santos might agree to a bilateral cease-fire to save the peace process. This is a miscalculation: public fatigue with the peace process makes it more likely that the government might walk away from the talks completely.

Oil spill from a FARC pipeline bombing in Nariño.

By improving security conditions, a bilateral cease-fire could halt the damage to public opinion, which in turn would allow negotiators more time and a calmer environment with which to agree on the difficult remaining issues. But getting there would not be easy.

A bilateral cease-fire could do more harm than good unless it comes with independent verification to investigate violations, agreement on the range of hostilities that must cease (for instance, whether it means immediately ceasing guerrilla fundraising through extortion and drugs), and perhaps agreement on concentrating combatants in zones where they could remain armed, but not be subject to attack (as ex-president Álvaro Uribe has suggested).

Will human rights abusers get jail time?

This has not yet been decided, and negotiators have only just begun to take it up. As these are not surrender talks, FARC leaders are unlikely to turn in weapons only to go to a jail. But Colombia, as a party to the International Criminal Court, cannot amnesty war crimes or crimes against humanity, as most past peace processes have done.

It is likely that negotiators will reach an arrangement that requires the worst violators on all sides to spend a reduced number of years in some condition of confinement. FARC leaders have insisted that they will not spend a day in jail for having rebelled. However, they have also said they would not rule out some sort of confinement for the most serious crimes, as long as similar sentences went to military officers and civilians who committed, aided, and abetted similarly serious crimes.

What will happen to the drug trade in Colombia?

The FARC is a major participant in Colombia’s drug trade, with available evidence indicating that the group uses the profits to supply itself, not for leaders’ personal enrichment. The guerrillas, though, are only one of several actors moving cocaine and other drugs out of Colombia: much production and transshipment is the work of organized crime, the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrilla group, and of “criminal bands”—armed groups descended from the pro-government paramilitary militias of the 1990s and 2000s.

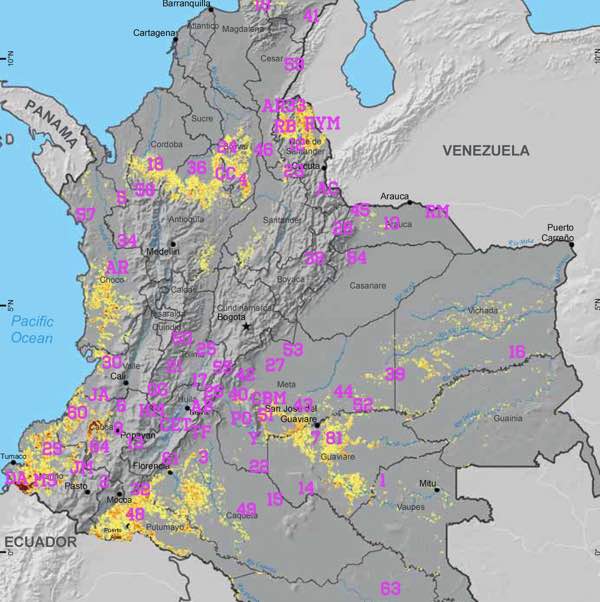

Locations of FARC fronts and coca-growing zones.

After a peace accord, organized crime and “criminal bands” will remain, and may be joined by some ex-guerrillas. These could easily fill any vacuum in the drug trade left by the guerrillas—unless the Colombian government and justice system move fast to establish a strong presence in traditionally FARC-dominated cultivation zones and trafficking corridors.

What about the ELN?

The FARC is not the only 50-year-old guerrilla group operating in Colombia: the ELN, with about 2,000 members, remains active as well. Since at least 2013, the Colombian government has held sporadic preliminary talks with ELN leaders, but has been unable to agree on an agenda and ground rules for formal negotiations. The ELN’s maximum leader said in April that negotiators are 80 percent of the way to a formal process, but obstacles remain. These likely include an ELN insistence on a bilateral cease-fire and on extractive industries’ inclusion on the negotiating agenda.

Closing a deal with the ELN is necessary because if it is still at large, the smaller group could absorb ex-FARC members who disagree with the decision to demobilize. So far, though, the Colombian government has devoted much less attention to the smaller guerrilla group, both at the negotiating table and on the battlefield.

What is Venezuela’s role?

Since at least 2007, Venezuela’s leftist government has faced allegations of harboring a FARC presence on its soil. There is little doubt that the FARC has encampments on the Venezuelan side of the two countries’ long border, that some FARC leaders spend time in Venezuela, and that these leaders have contact with Venezuelan officials.

The nature of this presence and these contacts is unclear. Venezuela’s borderlands are poorly governed, and Colombian organized-crime groups operate there just as easily as FARC does. Meanwhile, there is little evidence of direct material support from Venezuela’s government to the FARC. Captured FARC files indicate that high Venezuelan officials said “yes” to a request for generous funding in 2007, during a brief period when Colombia’s government authorized Venezuela to mediate with the guerrillas. We have no idea, though, whether any aid was delivered.

While a Venezuelan crackdown on FARC presence is difficult to imagine, Venezuela’s government has urged the FARC to give up violence, citing the ballot-box successes of leftist leaders there and elsewhere in the hemisphere. Today, Venezuela (along with Chile) is one of two countries “accompanying” the talks (Norway and Cuba are “guarantor” countries), and has played an important logistical role in transporting guerrilla negotiators to the table.

U.S. Special Envoy Bernard Aronson discusses the peace process with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in May.

How can the United States help?

U.S. engagement is important, and Special Envoy Bernard Aronson is playing a useful role. Though the talks are in a difficult moment, the likelihood of an eventual accord remains high, and the U.S. government should work with Colombia to prepare for a post-conflict phase. As the United States provided Colombia generous support during the worst years of its conflict, we must be prepared to stand with Colombia as it tries to consolidate peace.

Colombia will need help with international verification of both sides’ peace accord commitments and guerrilla disarmament; with demobilization and reintegration; and especially with the difficult work of getting a government presence in the historically neglected areas where drugs are produced and armed groups have thrived.

About 60 guerrilla leaders are wanted in the United States to face criminal charges, most for drug trafficking and some for attacks on U.S. citizens. If those wanted ex-guerrillas are truly respecting their commitments under the accords, including fulfilling responsibilities to their victims, then the U.S. government should accommodate Colombia’s likely decision not to extradite them.