(AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

(AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

This post was first published on March 22 and was updated on March 23.

Under the Trump administration, the FY2018 budget has involved a bitter fight over border spending and immigration policy. After two government shutdowns and five short-term spending bills, congressional leaders have agreed on a $1.3 trillion spending package. The omnibus appropriations bill, which will fund the federal government through Sept. 30, passed the House Thursday and the Senate early Friday morning, and President Trump, after threatening to veto the bill, said he signed it on “national security grounds.”

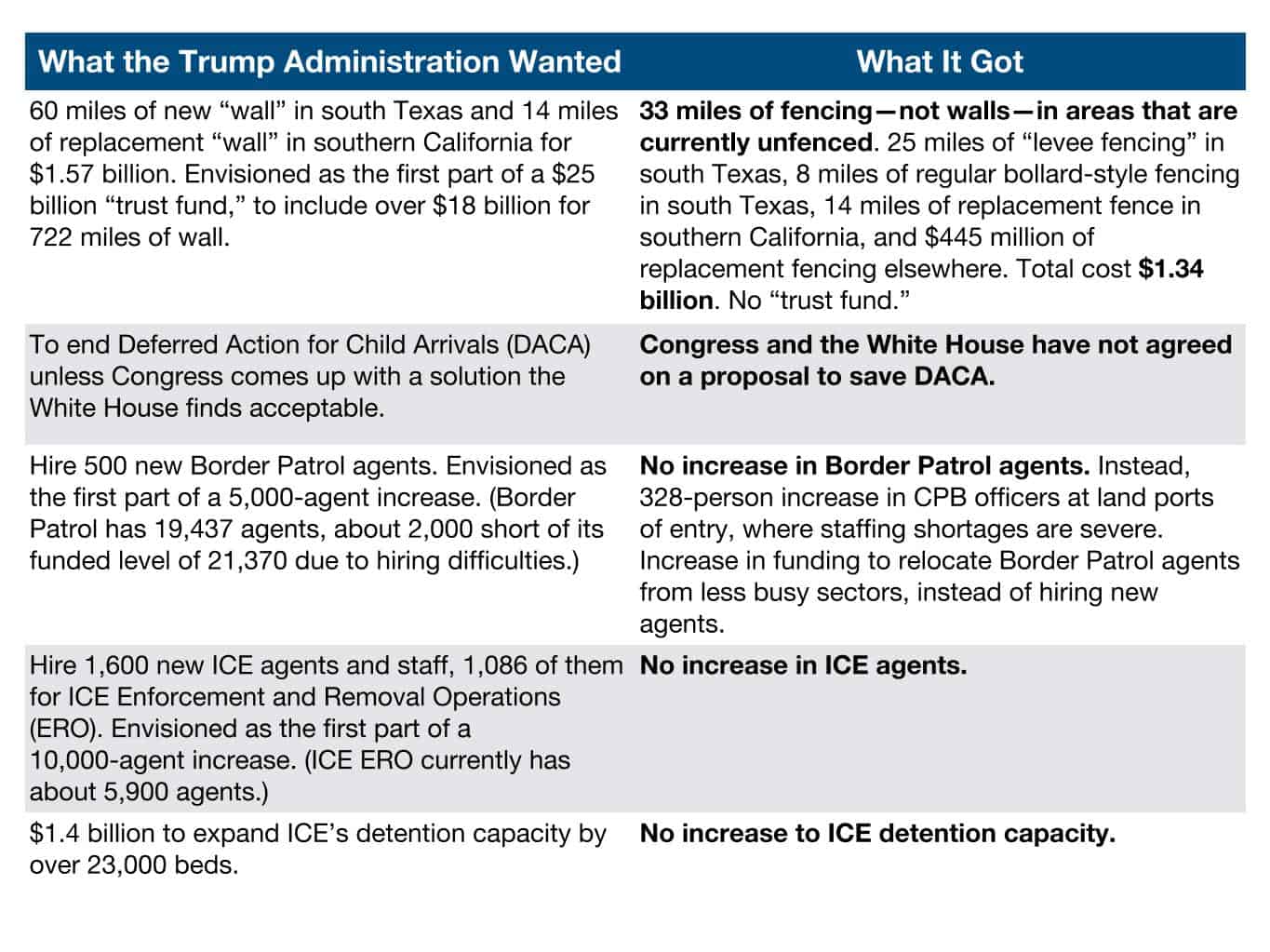

The FY 2018 omnibus appropriations bill represents a significant rejection of the Trump administration’s immigration and border security policies. The bill does not include anything close to the $25 billion “trust fund” that the White House wanted for a U.S.-Mexico border wall. Nor does it include spending for increasing the size of the Border Patrol. Nor is there funding for more Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) hires or beds in detention centers. Funding these draconian measures would have facilitated even more tearing apart of immigrant families and locking up asylum seekers requesting protection in the United States.

The bill does not, however, overturn the anti-immigrant executive actions put in place during the Trump administration’s first year. It doesn’t provide any permanent relief for the nearly 800,000 recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which Trump terminated in September 2017 but who are allowed to renew their permits after court rulings in recent months. Nor does it do anything for approximately 320,000 people—200,000 Salvadorans, 60,000 Hondurans, 50,000 Haitians, 2,500 Nicaraguans and others from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia—who are at risk of losing their temporary protected status under this administration and who may face deportation.

Click to enlarge the infographic:

The proposed budget also rejects the Trump administration’s demands for massive cuts to foreign assistance to Latin America (which the White House has also requested for FY2019). It proposes more or less the same amount of aid as was approved in 2017 (and the same types of aid) to Colombia, which could help support further implementation of the country’s historic 2016 peace accords.

However, language in the bill would tie Colombia aid to progress on reducing “overall illicit drug cultivation, production, and trafficking.” If the State Department finds that Colombia hasn’t made such progress, it must cut economic aid and—even more strangely—counter-drug aid by 25 percent. This puts pressure on Colombia to show short-term results against the more than 115,000 families currently living off of the coca economy, ignoring the need for a long-term solution as envisioned in the peace accord, and risking more abuses against civilians.

On Mexico, the House bill increases funding slightly from levels approved for FY2017, and rejects the White House’s proposal to cut fundings levels by some 36 percent compared to FY2017.

On Mexico, the Senate’s report accompanying the bill, which the final legislation directs the State Department to follow, includes language asserting that 25 percent of U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) to Mexico will be contingent on Mexico making progress in “thoroughly and credibly investigating and prosecuting violations of human rights in civilian courts, including the killings at Tlatlaya in June 2014 and the disappearance of 43 students at Ayotzinapa in September 2014, in accordance with Mexican law.” The funding will also depend on whether the United States can determine that Mexico has made progress against the use of torture and in “searching for the victims of forced disappearances and credibly investigating and prosecuting those responsible for such crimes.” The insertion of this language in the bill is a strong recognition by Congress of the Mexican government’s need to make substantive progress in its respect for human rights within the framework of security operations and efforts to strengthen the rule of law in the country. The addition of $1 million in funding for Mexico’s Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Freedom of Expression is also important given the threats facing reporters in Mexico and the almost complete failure to investigate these crimes and prosecute those responsible.

Proposed funding for Central America in the House spending bill rolls back the White House request for a 30 percent aid cut from 2017 levels, and instead recommends the same level of aid to the region that the House requested in its July 2017 spending bill. (The House bill had called for slightly more assistance than the Senate bill.) It maintains programs to reform security and justice institutions, addressing the root causes of the past few years’ increased migration from Central America. It also keeps in place necessary requirements that the region’s governments show progress on human rights and institutional reforms to be eligible for some assistance.

By and large, the FY2018 spending bill rebuffs the Trump administration’s spending priorities on immigration and border security, as well as foreign aid to Latin America. As has been widely reported, the Trump administration tried to force Congress to accept $25 billion in upfront funding for the border wall, but refused to offer meaningful action on a DACA fix. This legislation is a significant rejection of that posture, and of Trump’s inhumane and wasteful immigration and border security policies. But we cannot celebrate as long as legislation continues to fail to deliver permanent legal status for DACA recipients, and for the Haitian, Salvadoran, and Nicaraguan families who face deportation because the Trump administration has ended their protected status.

Geoff Thale and Maureen Meyer contributed to this article.