House Republicans are pushing a new border bill that would punish political appointees for not obtaining the impossible: “operational control” of the border in five years, a standard that would be expensive, disruptive, and ultimately unworkable.

“If operational control of the border is not gained in two years for high-traffic areas of both the southern and northern border—and five years for the entire southern border—political appointees at DHS will face automatic consequences.”

— Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), chairman of the House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, introducing H.R. 399, the “Secure Our Border First Act of 2015,” January 21, 2015.

By a party-line vote of 18 to 12, the House Homeland Security Committee approved the “Secure Our Border First Act” on January 21st. The Republican leadership has pulled the bill from the House floor, delaying the vote ostensibly due to inclement weather. But The Hill reports that it was derailed because of objections from conservatives, and may be paired with another measure in the House Judiciary Committee. It is likely off the table for now but might resurface in February.”

Much of the bill [PDF] specifies new equipment, aircraft, and facilities for Border Patrol and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). It does not roll back protections of unaccompanied Central American children, as House-passed legislation sought to do last July. Except for US$35 million to reimburse state governors who send the National Guard to the border, the bill also avoids further use of the U.S. military at the border. It requires Border Patrol to respond more flexibly to geographic shifts in border crossings. And it would demand much more transparency about actions and results from Border Patrol, CBP, and the Department of Homeland Security.

The most perplexing part of the bill, though, is its insistence on a very rigid term, “operational control,” to judge whether the border is secure.

For this and other balanced analysis of border security issues, see WOLA’s blog: Border Fact Check: Separating Rhetoric from Reality.

If U.S. authorities do not achieve operational control in high-traffic areas of the U.S.-Mexico border within five years, Section 3(o) of the bill would punish them. Political appointees anywhere in the Department of Homeland Security—that is, most top leadership—would be prohibited from travel using government aircraft, unable to receive any non-essential training or attend conferences, and they would be banned from salary raises or bonuses.

But what does operational control mean? The bill refers us to the language used in the Secure Fence Act of 2007. It reads:

(b) Operational Control Defined.–In this section, the term “operational control” means the prevention of all unlawful entries into the United States, including entries by terrorists, other unlawful aliens, instruments of terrorism, narcotics, and other contraband.

In other words, operational control means zero unauthorized border-crossers, including migrants, in “high-traffic areas.” This is a tremendously unrealistic standard.

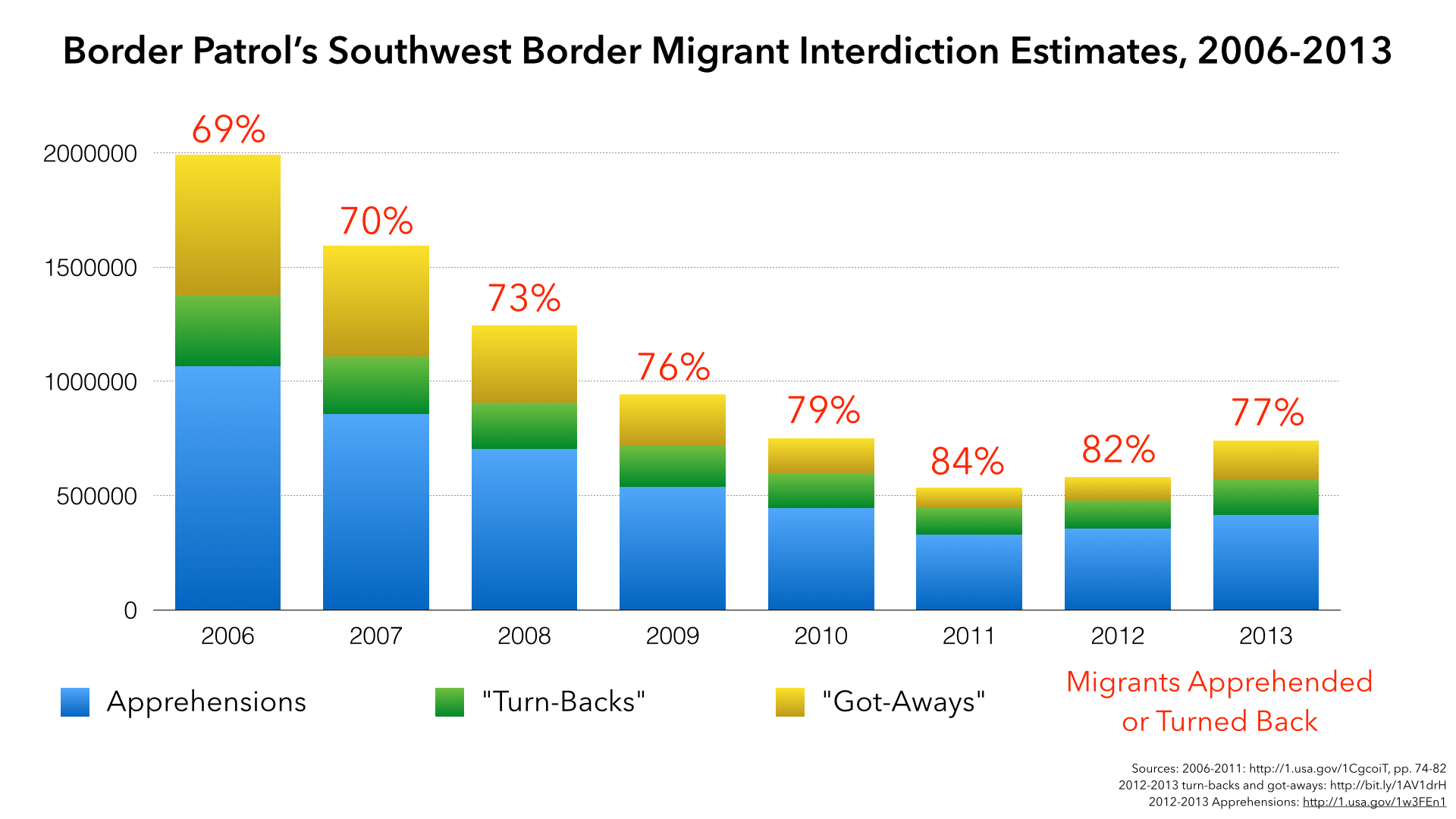

For proof of its unreality, consider data presented by a 2012 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report (covering 2006–2011), and through a recent reply [PDF] to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request submitted by theNational Security Archive (covering 2012 and 2013).

In these sources, for each year between 2006 and 2013, Border Patrol offers its best estimate of undocumented people it apprehended, those who avoided capture but returned to Mexican territory (“turn-backs”), and those who avoided capture and entered the United States (“got-aways”). Border Patrol estimates got-aways using information from sources including pursuits, surveillance, and detection of tracks on the ground. It is a rough estimate, and the FOIA document warns that the 2012 and 2013 estimates are “unofficial.”

However inexact, the data show Border Patrol agents capturing, or turning back across the border, a much greater proportion of migrants in 2013 than in 2006. In recent years, only about one out of every four or five border-crossers “gets away.” But even in the most controlled sectors of the border, the proportion of apprehensions and turn-backs is nowhere near the almost 100 percent that operational control would require.

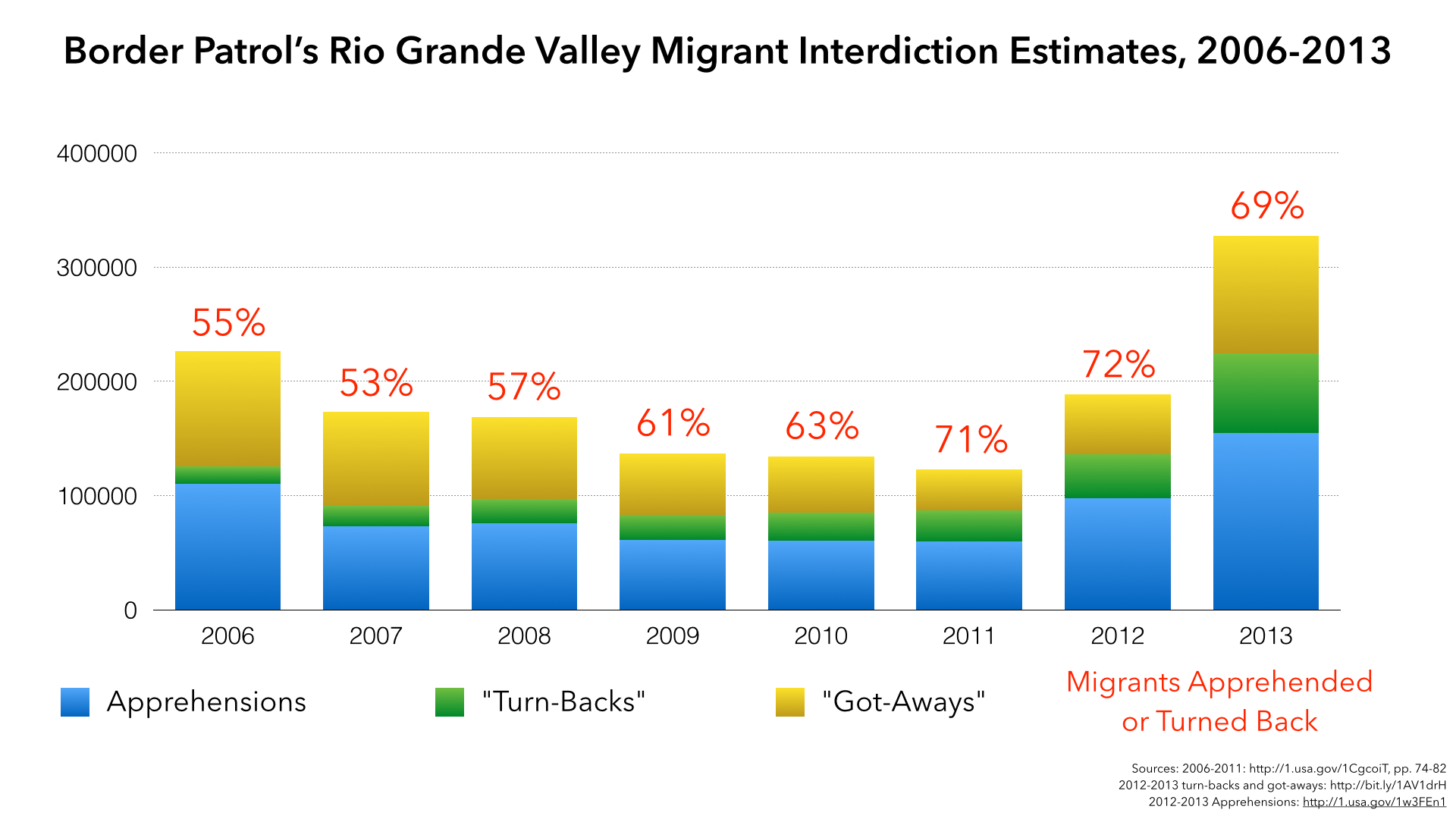

The data show a decline in the percentage of apprehensions and turn-backs, as a total of border crossers, in 2013, the last year for which estimates are available. That decline owes almost entirely to a higher number of got-aways in Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley sector, in south Texas. The number of migrants headed to the Rio Grande Valley, most of them Central Americans, has jumped upward since 2012 even as migration has remained the same, or declined, elsewhere along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Another possible but unconfirmed reason for the 2013 increase in “got-aways” could be that U.S. authorities are simply seeing more of them than before, thanks to improved surveillance technologies. Airborne radars like the Vehicle and Dismount Exploitation Radar (VADER) system, which was mounted to drones [PDF] in Border Patrol’s Tucson and Rio Grande Valley sectors in 2013, may have detected more border-crossers, often in areas too remote for Border Patrol agents to arrive in time to apprehend them. (Tucson, which saw the most VADER use that year, saw a jump in “got-aways” from 22,282 in 2012 to 37,098 in 2013. We do not know the extent of any correlation.)

The numbers make clear that the current definition of “operational control” is too high a standard to apply to a complicated law enforcement problem along a 1,960-mile border. The type of fortification that would be needed to achieve “operational control” in high-traffic areas is far more expensive, and more disruptive to border-area residents, than the bill’s authors seem to realize.

For instance, Section 3(b)(9) mandates more surveillance and rapid-reaction capability for the Rio Grande Valley sector. But it does not take the expensive and locally unpopular step of building more fencing in a sector where the border wall covers 54 of 314 miles of twisty Rio Grande riverbank.

Even this bill is not prepared to provide the draconian, quasi-military, and budget-busting tools and law enforcement presence that would be required to achieve true “operational control” in a region like the Rio Grande Valley. Even to try for such perfection would be foolish. By rigidly adopting that standard, the “Secure Our Border First Act” misunderstands the reality at the border.