AP Photo/Marco Ugarte

AP Photo/Marco Ugarte

Mexico’s Congress is hastily debating a law to regulate the involvement of the armed forces in public security. The discussion fails to address the implications of further militarizing Mexico’s public security and civilian authorities’ inability and lack of will to investigate and prosecute soldiers implicated in human rights violations and crimes.

In 2006, then-President Felipe Calderón increased dramatically the deployment of Mexico’s armed forces to combat organized crime in the country as a temporary yet urgent measure. As with past efforts to militarize public security in Mexico, Calderón argued that a military presence was needed until federal, state, and municipal police forces could fully assume their public security role. He affirmed that strengthening and professionalizing civilian police forces, particularly the federal police, would be prioritized in the meantime.

More than ten years later, the Mexican Army and Navy are still deployed to support federal, state, and local police in public security tasks. In October 2016 it was reported that soldiers participated in operations in 23 of Mexico’s 31 states as well as Mexico City. After receiving pushback from General Salvador Cienfuegos, the National Defense Minister (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional), about the military’s lack of a legal framework to participate in public security operations, Mexico’s Congress is now rushing to discuss and approve a Law on Internal Security (Ley de Seguridad Interior). The different proposals that have been presented would give the president the power to deploy soldiers to protect a vaguely defined “internal security” in the country and also permit state and local governments to request military presence.

With this law, Mexico’s Congress seeks to expand and normalize the military’s presence in public security rather than critically assess the impact of more than a decade of military deployment in the country which has failed to effectively reduce violence and organized criminal activity. The use of the military in operations to combat organized crime and in public security tasks has also resulted in grave human rights violations perpetrated by soldiers, including documented cases of torture, enforced disappearance, and extrajudicial execution.

It is expected that the Law on Internal Security will be discussed during the first session of Congress, which ends in April. As the law is debated, it is important to consider the human rights implications for legally entrenching the military’s role in public security. The failure to strengthen the ability and will of Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office to investigate and prosecute human rights violations and crimes committed by soldiers against civilians will result in continued impunity for these crimes and will not help deter future abuses.

Police and soldiers are not interchangeable. Military forces are trained for combat situations in which force is used to overwhelm an armed enemy. Police are a civilian corps, trained to address threats to public security while using the least amount of force possible and to address crime with the cooperation of the people. As Mexicans have experienced for over a decade, there are inherent risks in having military-trained forces in close contact with the civilian population.

During these years of military deployment, soldiers have perpetrated crimes and human rights violations against civilians; many of the cases have been documented by government authorities. In 2014 Mexico’s Congress enacted reforms to the Military Code of Justice to address the failure of the military judicial system to obtain justice for victims of crimes and human rights violations. These reforms granted the federal Attorney General’s Office (Procuraduría General de la República, PGR) jurisdiction over crimes committed by the military against a civilian. While the reforms were important, many obstacles remain.

Some cases of crimes and human rights violations committed by soldiers have been investigated and sanctioned; however, compared to the gravity of the crimes and the limited results of criminal investigations, these developments are insufficient. Amongst the crimes under investigation and being tried in court are cases of homicide, enforced disappearance, torture, rape, assault, perjury, abuse of authority, possession of narcotics, and organized crime.

WOLA is currently researching the progress made by civilian authorities to investigate cases involving Mexican soldiers. Our preliminary findings show that there are at least three ways in which the civilian criminal justice system is falling short in the investigation of these cases.

1. Poor implementation of legal reforms

While the 2014 reform to the Military Code gives the PGR the power to investigate crimes and human rights violations committed by soldiers against civilians, in practice the military exerts important control over the PGR’s investigations. So far, authorities have failed to guarantee the primary goal of the reforms: to grant civilian authorities effective control and leadership over investigations into crimes perpetrated by soldiers against civilians and to sanction those responsible.

According to testimonies obtained by WOLA, the PGR’s investigations into crimes committed by soldiers are slow, bureaucratic, and not transparent. Case files and documents from Mexican judicial authorities as well as interviews with human rights organizations on cases involving soldiers implicated in forced disappearances and extrajudicial executions have shown the failure of prosecutors to obtain military documents and testimonies for the PGR’s investigations and the existence of parallel investigations in military and civilian jurisdictions for the same case. This has the effect of prioritizing investigations in the military justice system and impeding effective and prompt civilian investigations. In the well-publicized case of the Tlatlaya massacre, in which 22 civilians were killed by soldiers and where the CNDH concluded that between 12 and 15 people were extrajudicially executed, military authorities had de facto control over the investigation. To date, the soldiers implicated in the case have not been sanctioned in civilian jurisdiction as a judge ruled in May 2016 that the PGR had failed to present evidence to support the conviction of the three soldiers accused of homicide and altering the scene of the crime.

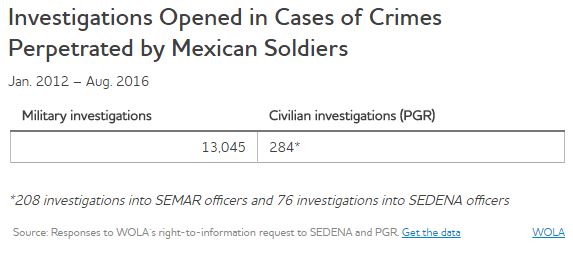

The following chart illustrates how military investigations still outnumber civilian investigations in crimes perpetrated by the military.

The PGR’s bureaucracy and lack of proper planning to investigate crimes committed by the military has led to the misleading narrative that the military judicial system is faster and more effective than the civilian system in investigating soldiers. This is not so. The military justice system is inadequate for human rights accountability: it is focused only on investigating and sanctioning military offences, meaning victims and uncovering the truth are not priorities. Military crimes set forth in law are limited and military investigations do not permit inquiry into the orders that soldiers receive and who should be held accountable for the crimes and human rights violations that occur as a result of following these orders—including high-ranking officers or civilian authorities.

2. The failure to prioritize cases involving soldiers

Prosecution of crimes in Mexico is highly politicized and it seems that prosecutors in the PGR have not received orders to prioritize and professionally investigate crimes perpetrated by soldiers.

Despite the fact that the transfer of cases from military to civilian jurisdiction started in 2012, PGR’s Operational Plan for 2013-2018 did not include plans for the investigation of crimes committed by members of the military, meaning there are no specific and transparent strategies in place to investigate these cases. Investigations of crimes perpetrated by the military are scattered in at least eight different offices within the PGR, reproducing the fragmentation of cases and bureaucracy that has impeded effective and professional criminal investigations in Mexico for decades.

The coordination between the PGR and the military to investigate crimes is not transparent and procedures to refer cases to civilian authorities appear to be arbitrary. The only two public cooperation agreements between the military and the PGR—signed in April 2012 and November 2012—do not contain specific provisions for military cooperation during the PGR’s investigations of crimes perpetrated by soldiers.

3. The failure to investigate the chain of command, high-ranking officers within the military and civilian institutions who gave orders that resulted in crimes being committed, or those who failed to take action to prevent or punish crimes.

Crimes committed by soldiers are investigated by the PGR on a case-by-case basis, which fails to take into consideration the fact that they occurred in a context of soldiers being tasked to combat organized crime. Beyond the acts themselves, criminal investigations must look into the orders, actions, and omissions from high-ranking officers and civilian authorities. For example, the PGR has still not investigated the chain of command in the Tlatlaya massacre, despite the fact that the soldiers were operating under a standing military order that directed them to patrol at night and take out criminals.

The PGR’s investigations are also a fundamental tool to hold civilian authorities accountable for their responsibility in deploying the military and the crimes and human rights abuses that have resulted from the military’s expanded role in public security. There is no public and reliable evidence that demonstrates that the PGR is pursuing these lines of investigation in any case.

Any legislative discussion on the role of the military in public security should include a plan to gradually return soldiers to their barracks, rather than solidifying their presence in public security tasks. An essential component to this will be enacting initiatives to strengthen and professionalize Mexico’s civilian police forces.

Likewise, Mexico’s Congress must also be mindful of the human rights implications of deepening the military’s involvement in public security operations. Focusing on a law that would provide a legal framework for the military to operate in public security functions while failing to acknowledge the thousands of victims of crimes and human rights violations committed by members of the military will send the message that justice, transparency, and accountability are not a priority for the government. Mexico urgently needs a functional criminal justice system to investigate and prosecute soldiers implicated in human rights violations and crimes.