(AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

(AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

This piece has been amended to note the October 21 announcement that the OAS Secretary General’s office and the government of Nicaragua will create a special commission to assess the political and electoral situation in the country, though its report will be released after the elections.

On November 6, Nicaragua will elect the country’s next president, as well as 90 members of the National Assembly and representatives to the Central American Parliament.

Nicaragua has been a source of debate in the United States since shortly after the Somoza dictatorship was overthrown in 1979. U.S. analysts and politicians alike saw the country and its development through the lens of the Cold War, and judgments about both political and economic events there have continued to be colored by political sympathies. Even today, this polarization remains and there is a persistent lack of balanced analysis.

An impartial observer would note that the Ortega administration has made important progress in reducing poverty, expanding economic growth and improving access to social services. While the country has the lowest level of GDP per capita in Central America, Ortega’s government has notably expanded access to public housing, education, and social services for the most marginalized Nicaraguans. According to World Bank figures, the poverty level has dropped from 42.5 percent in 2009 to 29.6 in 2014, with the share of those living in extreme poverty falling from 14.6 to 8.3 percent during the same period.

Nicaragua has notably expanded access to public housing, education, and social services for the most marginalized Nicaraguans. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

These are real and important advances, and they have won the Ortega government extensive public support. Polls show that President Ortega is very popular in Nicaragua, and that he is favored to win reelection by a large margin. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) leader enjoys the support of 64.2 percent of those surveyed, compared to 8.3 percent for his nearest rival, Maximino Rodriguez of the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC). The political opposition has faced pressure from government, but also suffers from ongoing internal divisions.

Another factor contributing to public support for the government is the comparatively low level of crime, as Nicaragua has done a better job than most of its neighbors in controlling crime and violence. Homicide rates in Nicaragua, though higher than in the United States, are far lower than in the countries of the Northern Triangle, and youth gangs, though a persistent problem, are less violent and less organized than elsewhere. The Nicaraguan National Police, while not without flaws—they have not always protected the right to protest when exercised by government opponents, and their once-sterling reputation has been blemished by charges of corruption and occasional brutality—have relatively strong investigative capabilities, and generally maintain a community-oriented approach to policing that contributes to the relatively low crime rate.

#Nicaragua has seen an alarming pattern in recent years: a gradual erosion of democratic institutions Click To TweetThe impartial observer would also note that, despite long-standing differences, the Nicaraguan and U.S. governments cooperate on a number of issues. The two countries cooperate on drug interdiction, especially along the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua. The United States has worked bilaterally with the Nicaraguan Navy and units of the Nicaraguan National Police in counter drug efforts, and offered training and financial support to specific units. The U.S. government has also praised Nicaragua for its implementation of the controversial Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR).

At the same time, the observer would also note that Nicaragua has seen an alarming pattern in recent years: the gradual erosion of democratic institutions, as President Daniel Ortega has consolidated power under the executive branch amid a growing lack of transparency. Worrisome democratic setbacks have been more and more conspicuous in the lead up to the upcoming elections, and loom large over the country’s social gains. What follows focuses on those setbacks.

In June, Ortega raised eyebrows when he announced that he would not allow international electoral observers to monitor the upcoming election, saying: “The observation stops here; let them go observe other countries.” Just a few weeks later the Supreme Court responded to a legal battle over internal control of the opposition Independent Liberal Party (PLI) by stripping Eduardo Montealegre of his position as party leader and siding in favor of Pedro Reyes, who has strong ties to the Ortega administration. The Court also invalidated the leadership of the smaller Citizen Action Party in a subsequent ruling.

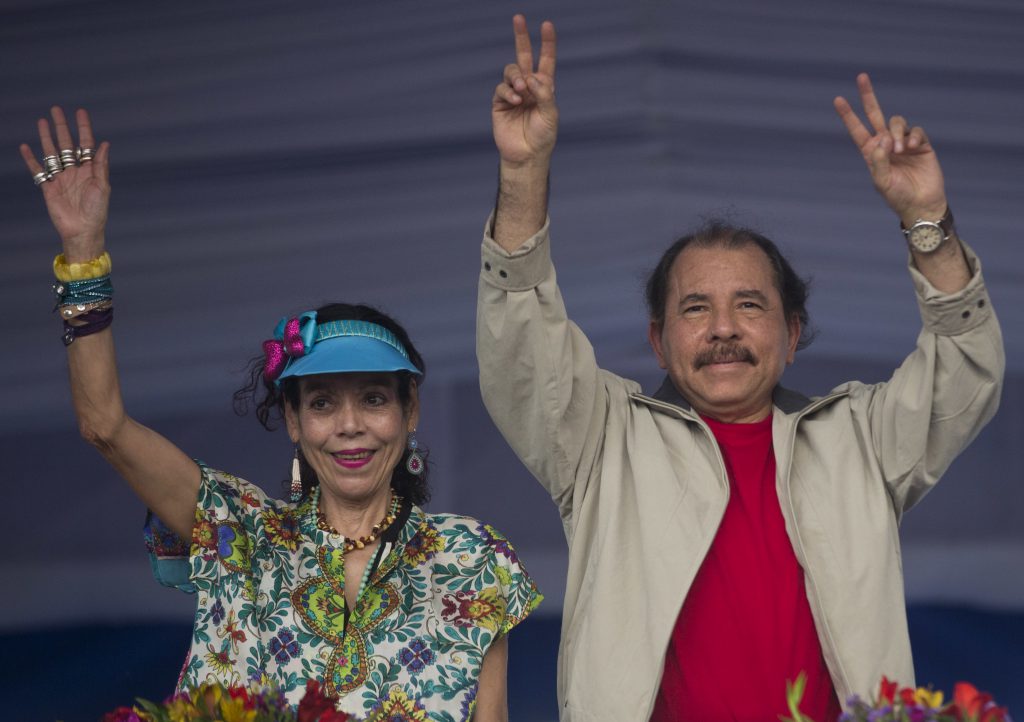

Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega, right, and first lady Rosario Murillo. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

Then, on July 29 the Supreme Electoral Council (CSE)—which is made up of magistrates elected by the FSLN-controlled legislature—stripped 16 PLI lawmakers and 12 alternates affiliated with Montealagre’s faction of their seats (including Montealegre himself). Because these lawmakers had refused to accept Reyes’ leadership of the party, the decision set off alarm bells and fueled accusations among the opposition that the government was attempting to pave the way for a one-party election. As a result, the PLI candidate has dropped out of the race and only opposition candidates from minor parties remain.

Yet another concerning development occurred days later, when Ortega selected his wife and communications director Rosario Murillo as his running mate. The president is rumored to be facing health problems, and at age 70, his decision to appoint his wife was seen by many as an attempt to cement a line of succession in his final years. These allegations have been fueled in recent weeks by Ortega’s repeated talk of a “joint government” with Murillo, who has already been running day-to-day operations like major speeches and public appearances for several years.

Concerns about the electoral process in Nicaragua are not limited to the upcoming November vote. As WOLA noted has noted previously, both the 2011 general election and the 2008 municipal elections were marked by irregularities in the voter registry and provision of voting identification cards, restrictions on election observation, and imbalances in the partisan makeup of official local electoral bodies.

Opposition figure Eduardo Montealegre was stripped of his position as party leader. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

These concerns have been shared by other international organizations. In a particularly vocal statement the Carter Center condemned the 2008 vote as one marked by “confirmed fraud,” and expressed distress at the CSE’s lack of commitment to political independence. The Carter Center did not field an observation mission in the 2011 elections out of concerns regarding the government’s election monitoring regulations but they did conduct a study mission, after which they concluded that the 2011 elections dealt a “debilitating blow to Nicaraguan democracy, and illustrating the limits of the Inter-American Democratic Charter and the practice of election observation.”

Similar grievances were expressed by other international observers for the 2011 elections, where Ortega was re-elected despite a constitutional ban on multiple terms, a move that was justified by a FSLN-appointed majority in the Supreme Court and later reinforced by a Constitutional reform passed by the party’s majority in the legislature in January 2014.

Nicaraguan civil society faces serious challenges, and polarization and disagreements at the local level are ongoing problems. FSLN-affiliated community organizations known as Citizens Power Committees (CPCs ) have influence in many communities because they administer government-funded antipoverty programs. Non-profit groups accused of being affiliated with the opposition, meanwhile, have faced claims of posing as fronts for money laundering and subversion.

Activists who have opposed the Ortega government as well as opposition party members and others calling for fair elections have at times been met with violent attacks, and, as noted above, the Nicaraguan National Police have on multiple occasions shirked their responsibility to protect opposition demonstrators. In May 2016, two lawyers with the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) who were traveling to Managua for human rights meetings and for the 25th anniversary celebration of the Nicaraguan organization Centro Nicaraguense de Derechos Humanos (CENIDH) were detained at the airport and deported from the country without any valid justification. Amnesty International indicated that in 2015 and 2016, “human rights defenders and indigenous and afro-descendant groups were threatened and intimidated in retaliation for their work, particularly in the context of public protests.”

Ever since it was announced in 2013, Nicaragua’s controversial plan to build a $50 billion canal to rival the Panama Canal with the help of a Chinese firm has been a rallying point for civil society groups. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

It has also become increasingly difficult for non-governmental organizations to receive outside funding. In September 2015 the government announced plans to prevent local organizations from receiving direct funding from international sources. Instead, these would be channeled through state institutions. Though the full scope of this initiative remains to be seen it has already stirred outrage, causing the director of the local UN Development Programme to leave her post in protest.

Ever since it was announced in 2013, the government’s controversial plan to build a $50 billion interoceanic canal to rival the Panama Canal with the help of a Chinese firm has been a rallying point for civil society groups. Opposition to the plan’s environmental impact from research groups like the Centro Humboldt, as well as to legislation that could authorize the displacement of rural residents and indigenous communities affected by the canal, has led thousands to participate in recurring protests.

Recent years have also given rise to concerns about a lack of transparency in the country regarding government actions. The international accountability NGO Transparency International ranks Nicaragua at 130 of 168 countries in the organization’s Corruptions Perception Index (CPI). The International Budget Partnership, meanwhile, notes in its annual Open Budget Survey that while Nicaragua publicized five of eight key budget documents in 2016 in a timeframe consistent with international standards, there are limited opportunities for the public to engage in the budget process. Shortcomings on transparency in Nicaragua have been made compounded by a strained media environment. Journalists in the country have complained of a lack of strong protections for their work in the face of threats, as well as a prevailing lack of access to President Ortega.

In the face of the situation in Nicaragua, many in the Nicaraguan opposition have appealed to the international community, even asking Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General Luis Almagro to take up the issue as he has done with Venezuela. On October 21, the Secretary General’s office announced it had reached an agreement with the Nicaraguan government to create a special commission to assess the political and electoral situation in the country and release a report about it. The two also agreed that Almagro could make a country visit on December 1 to speak with actors on the ground. However, both this visit and the publication of the report will take place after the elections.

The situation has also sparked interest from U.S. lawmakers. On September 21, the U.S. House of Representatives voted without objection to pass the “Nicaraguan Investment Conditionality Act” (NICA), which would instruct the U.S. government to oppose almost any loan to Nicaragua from international financial institutions until democratic concerns were addressed, coming on the heels of a September 15 hearing on the issue before the Western Hemisphere Subcommittee of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

The proposed NICA Act, if signed into law, would not be helpful in #Nicaragua. Click To TweetHowever, addressing concerns about democratic institutions in Nicaragua is not a simple matter for the United States. On one hand, the United States clearly has influence in the country. It is Nicaragua’s principal trading partner, and the two share a trade relationship under the terms of CAFTA-DR. As noted, also the Nicaraguan and U.S. governments cooperate extensively on counternarcotics operations. The United States has constructive working relationships with Nicaragua in the areas of security and commerce, which some government agencies value highly.

But direct influence is also limited: U.S. aid programs are relatively small (the U.S. Agency for International Development’s budget for Nicaragua in FY2014 was a modest $14 million) and U.S. agencies that work with the Nicaraguan government on security and trade wish to maintain their current cooperation.

Beyond this, a history of U.S.-involvement in the country dating back to U.S. support for the Contras in the 1980s and past interference in Nicaraguan elections—see remarks from OAS monitors of the 2006 elections—has contributed to a deep seated skepticism among the Nicaraguan public towards U.S. involvement in internal affairs. Efforts by the Embassy or the State Department to loudly denounce undemocratic practices are often counter-productive, as they allow the government to rally anti-American and nationalist support. As a result, State Department officials face limitations and dilemmas in raising concerns about democratic institutions.

The proposed NICA Act, if signed into law, would not be helpful in increasing U.S. influence. In fact, it is likely to diminish U.S. effectiveness. It feeds into the Nicaraguan narrative about U.S. interference, and is likely to cause a domestic backlash. Because it uses language and concepts lifted from the Helms-Burton Act enforcing the U.S. embargo on Cuba, it will lend itself to the notion in Nicaragua that critiques of the country’s human rights record are motivated by Cold War-style opposition to the Ortega government, rather than by concerns about democratic institutions.

Additionally, it would encourage the United States to oppose all loans from international institutions, meaning it could have a dramatic impact on much-needed humanitarian and development projects.

The reality is that the situation in Nicaragua is deeply concerning. But Cold War-era punitive measures that amount to collective punishment are not the solution.

The U.S and others in the international community have limited influence in Nicaragua. They should use their position to critique Nicaragua’s electoral and political shortcomings in a clear and balanced way, help preserve space for civil society and political debate, and support those actors in Nicaragua who advocate for human rights, indigenous and environmental issues, women’s rights, and other concerns that matter to Nicaragua and its people.