By Adam Isacson, Senior Associate for Regional Security Policy

“We’ll be the most militarized border since the fall of the Berlin Wall,” Sen. John McCain (R-Arizona) told CNN on June 25. The Senator was referring to a sweeping amendment to the immigration reform bill currently before the U.S. Senate, a bipartisan compromise that will launch what proponents are calling a “border surge” of new security measures along the United States’ frontier with Mexico.

With this amendment, the bill will allow undocumented immigrants to apply for Registered Provisional Immigrant Status after the Comprehensive Southern Border Security Strategy and the Southern Border Fencing Strategy have begun but they will not be able to embark on a “path to citizenship” until, among other requirements:

- The Border Patrol’s presence at the U.S.-Mexico border more than doubles, increasing to 38,405 agents from an end-of–2012 total of 18,516.

- Hundreds of miles of new border fencing are built, bringing tall, often double-tiered “pedestrian” fencing to 700 miles of the 1,969-mile U.S.-Mexico border.

- Authorities deploy a long list of new technologies along the border, including sensors, scanners, radar systems, and four new drone aircraft. The new drones are in addition to the 11 that Customs and Border Protection expects to deploy along the border by 2016.

Once the U.S. government adds all of this manpower and hardware to the border, the Senate bill would allow immigrants given provisional status to begin their “path to citizenship.”

That is good. But much else will happen. And it won’t be good.

1. It will cost a lot of money.

The amendment contemplates US$46.3 billion in new spending at a time of fiscal austerity. Consider the cost of just three of the proposed components of the “border surge”: hiring 20,000 Border Patrol agents, building or upgrading 700 miles of fencing, and deploying 15 drones.

- Extrapolating from the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the cost of hiring an extra 3,500 Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents, we can guess that it would cost over US$3.4 billion per year in additional funds to sustain Border Patrol with an extra 20,000 agents. These agents wouldn’t all be hired immediately, but the cost over 10 years would still be likely to exceed the $30 billion foreseen in the bill.

- The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has estimated that it costs an average of $3.9 million per mile to build a single-layer fence. A second layer costs about $2 million per additional mile. Let’s assume that only 400 miles of fencing needs that level of upgrading in order to reach the 700-mile threshold. That’s still $2.36 billion – and likely much more, since one reason fencing has not been built in many areas is the prohibitive expense of doing so in difficult desert, mountain, and riverbank terrain. In fact, the Senate bill language appropriates US$8 billion over five years—more than US$10 million per mile—for new fencing.

- In 2011, GAO reported that a Predator-B drone, like those in use at the border, costs the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) $3,234 per flight hour to operate. A 2012 report from the DHS Inspector-General indicated that each drone’s “desired capability” is to fly 13,328 flight-hours per year. $3,234 per flight-hour X 13,328 flight-hours per year X 15 drones = $646.5 million per year in operating costs. Add to this $72 million to purchase four more drones at $18 million apiece (the price cited in the DHS Inspector-General report).

2. People will keep trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

In 2011, GAO tells us, Border Patrol estimated that 533,571 border-crossers were apprehended, turned back, or got away (this number may count multiple border-crossers more than once).

Tests of new detection technologies indicate that the actual number may be somewhat higher than this. Still, it is a fraction of the number of people who attempted to cross as recently as 2000, when the number of apprehended border-crossers alone totaled 1,649,884.

Heightened security will probably reduce even further the number of attempted border-crossers. The total number of would-be crossers may even dip below half a million. Much will depend on economic growth in the United States, Mexico, and Central America: if the U.S. economy markedly outperforms the others, the reduction in migration will be less pronounced.

The fact remains, though, that even after the “border surge,” hundreds of thousands of undocumented individuals will seek to cross into the United States. Many will be among the record numbers of people deported from the United States in recent years, particularly those deemed inadmissible for provisional immigration status. A recent survey of deported Mexican migrants found that almost 75 percent of the migrants had previously lived and worked in the United States for an average of seven years, 28% said their current home was in the United States. Many more will be coming from countries, especially those in Central America’s “northern triangle,” whose extreme poverty and daily insecurity make the journey a risk worth taking.

With the “surge” expanding the security perimeter around border population centers, those who attempt the trip will travel through even more remote places. This is a phenomenon we have already seen over the past 20 years. The first attempts to seal border sectors, Operations “Hold the Line” and “Gatekeeper” in El Paso and San Diego in the early 1990s, caused sharp growth in migration through Arizona’s treacherous deserts. In the past few years, increased coverage in Arizona appears to be contributing to an increase in migration in South Texas.

The “border surge” will no doubt plug more gaps. But along a 1,969-mile border, gaps will remain. These will be in zones that are even farther from population centers. In coming years, keep

an eye on the borderlands of New Mexico and the Big Bend and Del Rio regions of West Texas. In 2011, these areas combined saw less than 60,000 attempted border-crossers, according to GAO. Expect this number to grow.

3. Of those who attempt to cross, more will die on U.S. soil.

In recent years, migrants’ movement to more remote, inhospitable, and treacherous areas has meant a jump in the number of migrants who die of dehydration, exposure, drowning, and other natural causes on U.S. soil. In 2012, Border Patrol reported 463 human remains found on the U.S. side of the border. This number, equal to about five migrants dying every four days, qualifies as a genuine humanitarian emergency.

|

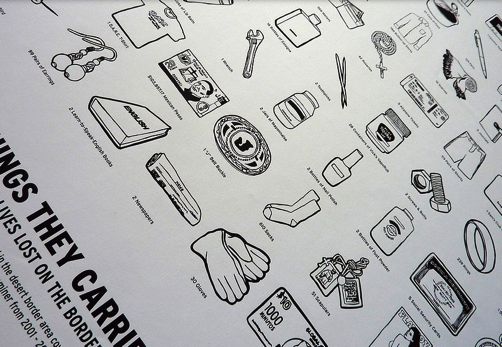

Detail from "The Things They Carried," a poster depicting personal items that the Pima County, Arizona Medical Examiner's Office found amid the remains of 1,573 migrants between 2000 and 2009.

|

It stands to reason that, following a “border surge,” migrants’ attempts to cross in even more remote areas will mean even more deaths. Even if they rise only slightly, more dead amid a smaller population of migrants would mean a record-high probability of a cross-border trip ending in tragedy.

4. For Border Patrol, very rapid growth spells trouble.

Today, even before any “border surge,” Border Patrol is one of the fastest-growing institutions in the federal government. The last time it doubled in size was between 2004 and 2011. By 2011, the agency had five times as many agents as it had in 1993. And now the Senate bill would have it double in size again.

If Border Patrol grows to 38,405 agents along the U.S.-Mexico border, less than 10% of the force there will have 20 years’ experience. Less than a quarter will have been in the organization even since 2005.

The vast majority will be inexperienced, and probably recruited and trained very hastily so that the requirement holding up the “path to citizenship” can be met. The hiring binge could let in some unqualified people. Meanwhile, any agency with so few experienced senior managers amid a mass of new hires is guaranteed to face some crippling managerial problems.

5. Abuses of migrants could multiply.

Advocacy groups, especially in Arizona and California, have already documented what appears to be a disturbingly frequent pattern of abuse of migrants in Border Patrol custody. The University of Arizona survey of 1,113 recent deportees in Mexico found episodes of abuse to be common. Meanwhile, Mexico’s government has voiced anger at the killing of at least 15 civilians, most of them Mexican, in confrontations with Border Patrol agents along the border since 2010.

These incidents have raised concerns about Border Patrol’s use-of-force guidelines (which are secret), its internal controls, and its procedures for dealing with allegations of human rights abuse. If the “border surge” doubles the agency’s manpower without bringing improvements to training and accountability, the number and frequency of abuses will grow still further.

6. Large amounts of drugs will still be smuggled through ports of entry.

Border Patrol operates between the 45 “land ports of entry” (POEs), or official border crossings, along the border. However, according to the Department of Justice, the majority of border-zone drug seizures—with the exception of marijuana—take place at the POEs. But the ports of entry are clearly a secondary priority in the “border surge” legislation.

The bill does increase manpower and infrastructure at POEs, but much less than it will do for Border Patrol. The addition of 3,500 Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials at the ports would represent about a 60 percent increase over current levels. This is less than the 100 percent increase that Border Patrol would receive, although it is still significant. Nonetheless, the bill appropriates relatively little money to expand infrastructure at the ports themselves.

More CBP officers will mean more seizures. But with only a few more scanners and a handful of additional inspection lanes at often dilapidated border crossings, the effect will be minimal. With border-crossing wait times routinely at or above two hours, the U.S.-Mexico border resembles a supermarket that refuses to keep enough cash registers open. As overworked CBP officers seek to inspect vehicles while keeping wait times down, illegal drugs, especially cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine, will continue to slip through in large amounts.

7. Border Patrol agents may find themselves with little to do.

In 2012, the average Border Patrol agent apprehended 19 border-crossers. In 2000, the average agent apprehended 192. In 1993 it was 327.

What will happen if a “border surge” reduces the number of apprehensions per agent to 10 per year, or less? Residents of border communities – which are already low-crime areas &nd

ash; should expect more roadblocks, more searches, and more ID checks. Along with these, they should expect more complaints about civil liberties violations, which will be compounded by the fleet of surveillance drones flying overhead.

Instead of seeking to re-create the Berlin Wall experience along a 1,969-mile border, a “border surge” would do better to focus its resources elsewhere. For instance:

- At our outdated and outmoded ports of entry, through which pass most drugs and a large minority of undocumented migrants.

- On expanded search and rescue capabilities, from rapid response teams to water stations and rescue beacons, to alleviate the human tragedy of hundreds of migrants dying on U.S. soil.

- On expanded efforts to help beleaguered state and county officials to identify remains of deceased migrants, and link them to bereaved family members.

- On enhanced training and improved internal accountability procedures for existing agents of Border Patrol and other law-enforcement agencies with border security responsibilities, all of which have grown very rapidly in the past several years even without a “border surge.”