(U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Rio Grande Valley Sector via AP)

(U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Rio Grande Valley Sector via AP)

Yesterday, the House Oversight Committee held a hearing entitled “Kids in Cages: Inhumane Treatment at the Border” to address the most recent government reports of squalid conditions in U.S. detention facilities and mistreatment of migrants by U.S. immigration authorities. Members of the public flooded into the hearing room wearing stickers with the hashtag #JusticeforMariee, a 19 month old child who died shortly after falling ill in an ICE facility in Dilley, Texas. Mariee’s mother, Yazmin Juarez, stated before the Committee, “It can’t be that hard in this great country to make sure that the little children you lock up don’t die from abuse and neglect.”

While Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported a decline in apprehensions at the southwest border during the month of June, children and families continue to flee Central America at record levels. Instead of better preparing U.S. agencies to deal with heightened numbers of vulnerable Central Americans, the Trump administration has enacted policies like metering at ports of entry and “Remain in Mexico,” that inflict more harm on migrants and contributed to more chaos.

In a new analysis, the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) highlights 10 critical points that no policymaker should ignore if we wish to see an end to this chaos.

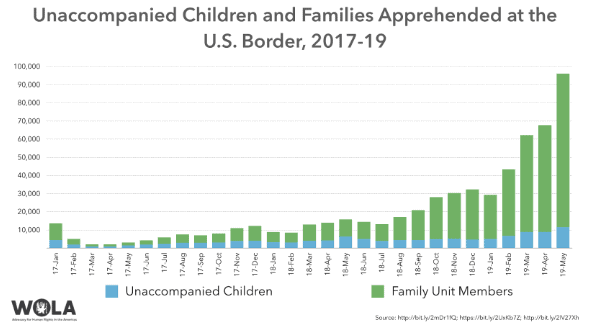

The number of migrants U.S. authorities apprehended at the southern border declined in June compared to May, the heaviest month for migrant arrivals at the border since 2007. (The context is very different, though: unlike 2007, when nearly all apprehended migrants were single adults, over two-thirds of migrants apprehended in May were children and parents.)

Harsh policies like “Remain in Mexico” and Mexico’s U.S.-imposed National Guard crackdown on migration, discussed in points 4 and 7 below, contributed to the decline. But so did seasonal variations: the border is scorchingly hot in June, and declines are normal. Migrant smugglers also likely pulled back operations in response to the crackdown. They haven’t gone out of business: they are more likely in “wait and see” mode as Mexico deploys as many as 21,000 guardsmen.

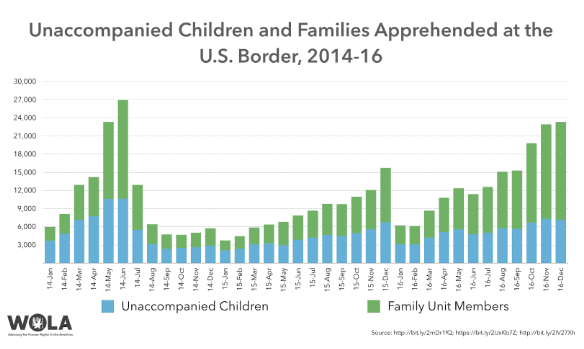

The decline, then, doesn’t mean that the humanitarian crisis at the border is “solved.” We’ve seen this before. A mid-2014 crackdown in southern Mexico, known as the “Southern Border Plan,” contributed to a similar drop in child and family migration. We saw a sharp drop as well in early 2017, as smugglers paused following Donald Trump’s inauguration.

Both times, after bottoming out after a few months, child and family migration began to increase again. After a 2014 wave of children and families, migration declined until January 2015, then gradually increased almost every month—there was almost no summer decline in 2015—until late 2016 saw a return to near 2014 levels. A similar pattern happened after Trump’s inauguration; after an initial drop, border apprehensions grew, with nearly every month greater than the last since April 2017.

The reason for these gradual recoveries is that migrants, and migrant smugglers, adjust. They adopt new routes through Mexico. Smugglers corrupt officials, such as those manning checkpoints, with near-total impunity. There is little reason to expect that this time won’t be different, since the forces driving people to leave Central America remain as intense as ever.

High homicide rates, death threats, domestic violence, and weak governments unable to provide protection to their citizens create situations in which many Central Americans feel compelled to flee for their own safety and that of their children. These problems are aggravated by high unemployment rates, lack of opportunity, and severe drought and crop failures in rural areas.

Helping reformers in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras make their countries safer, more prosperous, and more livable—thus alleviating many of the root causes of today’s migration—is a worthwhile mission for generous U.S. assistance. Getting there, though, would require sustained effort over a generation. In the meantime, assistance should be targeted at improving conditions in the communities sending the most people, and reducing the corruption that allows miserable conditions to flourish.

Inexplicably, the Trump administration has done the opposite. In a fit of pique over migration flows, the president has reprogrammed away about $550 million in assistance to the region that was appropriated for 2017 and 2018.

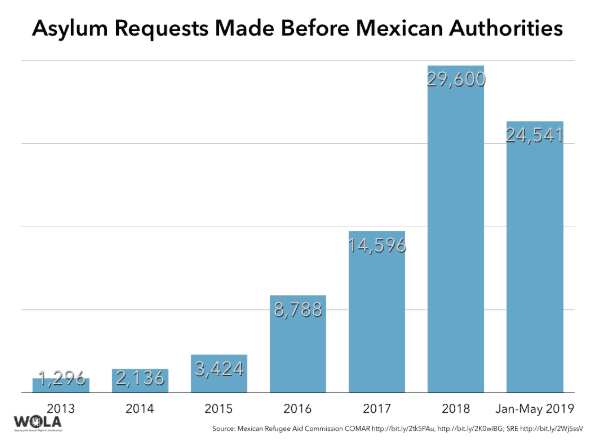

Applications for asylum in Mexico have roughly doubled every year since 2014, and are on track to do so again in 2019. The demand has overwhelmed capacity at Mexico’s refugee agency, COMAR, which has just a few dozen staff and an annual budget (not counting assistance principally from UNHCR) of just $1.2 million. The agency is near collapse. Mexico needs to invest more in its asylum system, but the current government has instead subjected COMAR to austerity measures, bringing its budget to its lowest level in seven years.

A growing number of Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran asylum seekers are heading south, to Costa Rica and Panama. Those receiving countries, too, will need assistance to accommodate the flow.

Especially if they are unable to obtain a legal status in Mexico, Central American migrants are victimized with shocking frequency there by gangs, organized crime, and corrupt officials. In some cases, the assailants are linked to the same violent Central American groups that the migrants are fleeing. Many do not feel safe in Mexico, and understandably seek to come to the United States.

With protection-seeking children and parents now the vast majority of migrants apprehended at the border, the U.S. government must adjust its asylum system to administer this increased demand. This means making it possible for asylum seekers to approach official ports of entry (land border crossings) and ask for protection, then—rather than sit in the small and now perilously overcrowded holding areas that CBP maintains at the ports —be taken to processing centers with sufficient space and personnel to begin their applications.

Instead, CBP has instituted “metering,” sending agents to the borderline outside ports of entry to prevent asylum seekers from setting foot on U.S. soil, and accepting only small numbers into the ports each day. This has caused at least 19,000 asylum seekers to spend months in Mexican border cities, usually with no stable incomes, waiting for their turns to come up on improvised waitlists. Many give up on the wait and seek to cross between the ports of entry, climbing fencing, crossing the Rio Grande, or walking in the desert. Many, including several children, have died.

This reality of being able to approach ports of entry is even more distant now that Mexico’s government, under intense pressure from the Trump administration, has deployed about 21,000 members of its new National Guard to its northern and southern borders. National Guard personnel—most of whom were soldiers a month or two ago before undergoing hasty and limited training—are rounding up migrants and physically stopping them from crossing into the United States, even to seek asylum.

Section 1325 of Title 8, U.S. Code, a law going back to 1952, declares that crossing the border anywhere except a port of entry is a misdemeanor punishable with up to six months in federal prison. The law makes no exception for asylum seekers. With its “zero-tolerance” policy in 2018, the Trump administration sought to apply Section 1325 to nearly everyone, prosecuting asylum-seeking parents and tearing their children from them as they entered the federal criminal justice system.

Today single adults, including asylum seekers, continue to get prosecuted in federal courts under “Operation Streamline,” which began during the Bush administration. After a cursory trial, most spend some time in prison before being deported. This is a senseless waste of resources.

Repealing Section 1325, as presidential candidate Julian Castro and others have proposed, is common sense. Doing so doesn’t mean “opening borders”: migrants with no documentation or credible protection claims would still be subject to deportation. But it would mean an end to filling federal courts and prisons with migrants.

In an ideal scenario, asylum seekers would spend a day or two in a processing center that is well-equipped, and staffed by personnel trained in working with children and trauma victims. They would then be released into alternatives-to-detention monitoring programs, and would pursue their asylum claims in an immigration court system with the capacity to decide their cases as quickly as due process demands.

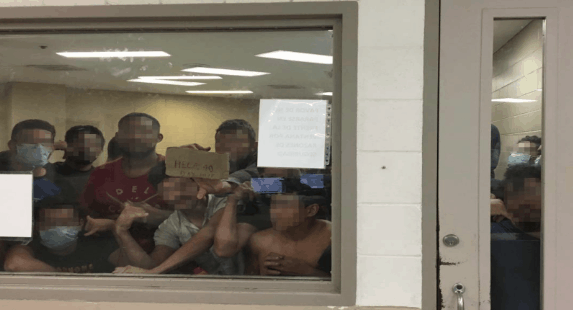

Instead, CBP’s processing capacity has collapsed, as evidenced by testimonies of families and children spending many weeks in fetid, overcrowded holding cells with no toothbrushes or opportunities to bathe, no food besides ramen noodles and burritos, and little or no outside contact.

“Help, 40 days here” reads a handwritten sign in a Border Patrol cell holding 88 men in a space intended for 41. The photo is from a shocking July report from the Homeland Security Department Inspector-General.

While there have been many accounts of cruel treatment, many if not most Border Patrol and CBP agents at these facilities have tried to do their best under impossible circumstances. Blame for these conditions lies with Homeland Security Department management, which failed to provide resources to improve processing (resources have been transferred quickly for priorities like ICE detention and wall-building, but not for processing) while preventing reports of horrible conditions from receiving scrutiny until recently.

If children come to seek protection on their own, the Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement must be well equipped to care for and place these children in safe environments. Given the urgent need to remove children from CBP processing facilities that have failed to provide adequate care, HHS needs more resources to quickly receive the current levels of unaccompanied children.

However, the increasingly common practice of using “influx facilities” is an immediate fix to a long term problem. These facilities lack government oversight and, in some cases, turn profits on vulnerable minors. Congress should fund only state-licensed facilities that provide consistent and well monitored services to unaccompanied children, working exclusively with non-profit, civil society organizations with experience providing comprehensive care. This care must include not just basic necessities of food and shelter, but also adequate health and legal services for each child.

Childrens’ stay pending resettlement must be made as humane as possible by making it as short as possible. Children under HHS guidance are confused, alienated from loved ones outside the walls of the shelters. Hiring more, vetted HHS caseworkers would allow for closer attention to each case, and children will be more efficiently placed in the safe care of relatives.

We remain enormously far from the ideal scenario described at this section’s beginning. The emergency supplemental appropriation approved in late June provides badly needed resources for processing recent arrivals. But the final bill tragically abandoned language establishing standards for the care and protection of children and families during their time in custody.

Following Trump’s threat—withdrawn, for now—to impose tariffs on Mexican goods, the Department of Homeland Security expanded the “Remain in Mexico” program, whose Orwellian official name is “Migrant Protection Protocols.” Under this initiative, which started at the beginning of the year, CBP has sent tens of thousands of asylum seekers back to Mexico to await their asylum hearings, which are months away due to court backlogs.

A hiring spree now could result in the addition of hundreds of judges who fit the Trump administration’s hardline anti-immigrant political profile, risking grave due process violations for people with strong and valid asylum and protection claims.

Upon their unexpected return to Mexican border cities, most asylum seekers—children, parents, pregnant women—are homeless. They have no sources of income. They are vulnerable and unsafe in cities with some of Mexico’s highest violent crime rates, and this week “Remain in Mexico” sank to an unconscionable new low by starting returns to Nuevo Laredo, a chaotic border city that is the home base of the intensely predatory, remnant factions of the Zetas cartel. While awaiting their hearings on the other side of the border, Remain in Mexico victims are having a very difficult time getting representation and receiving notifications about their asylum processes.

More than 18,000 migrants have been compelled to remain in Mexico, as of the first week of July. Add about 20,000 or more on port-of-entry waitlists, and there are now roughly 40,000 asylum seekers eking out a precarious existence in Mexican border cities. The Trump administration has signaled an intention to ramp up “Remain in Mexico” to 1,000 asylum seekers per day; at that rate, there could be over 100,000 by this fall. Mexico’s border cities can’t sustain that. We will start seeing harrowing images of squalid, disease-ridden migrant slums and encampments.

The Trump administration is leaning very hard on Mexico and Guatemala to go even further, signing on to a “safe third country” agreement. This would compel both countries to accept any asylum seekers who enter their territory en route to the United States, and enable the U.S. government to deport them permanently to Mexico or Guatemala.

This is absurd. Mexico would end up inundated with Guatemalans, and Guatemala with Hondurans and Salvadorans, and both would have to accommodate tens of thousands of Cubans, Haitians, Venezuelans, Africans, South Asians and others who first enter their territory. Meanwhile, it is obvious to all but the most obtuse that Mexico and Guatemala are not safe countries for migrants. As a late-June letter from three House committee chairs notes, “The State Department’s 2018 Human Rights Reports on Guatemala and Mexico make it clear that Guatemala and Mexico do not meet these standards,” due to security challenges, insufficient legal frameworks, and dysfunctional asylum systems. The letter also asserts that the president does not have the constitutional authority to conclude safe-third country agreements without Congressional action.

The “Remain in Mexico” program must stop immediately. And demands for a safe third country agreement must cease immediately.

As of May 2019, according to Syracuse University’s TRAC Immigration database, there were 908,552 cases awaiting resolution in U.S. immigration courts, not counting hundreds of thousands more awaiting re-calendarization. With about 424 judges to try all of these cases, the average case now takes 727 days to resolve; in some courts it’s over 900 days. “The three largest immigration courts were so under-resourced that hearing dates were being scheduled as far out as August 2023 in New York City, October 2022 in Los Angeles, and April 2022 in San Francisco,” TRAC reports.

With the average immigration judge facing a load of at least 2,142 cases, the solution seems obvious: hire more judges and establish more immigration courts in order to reduce backlogs and wait times. With enough capacity, asylum cases could be resolved in a year, respecting due process. Asylum seekers would spend that year preparing their cases in the U.S. interior, while monitored by alternatives-to-detention programs (described in the next section). If the system worked this efficiently, people without clear asylum cases would be far less likely to pay smugglers several thousand dollars and uproot themselves in order to stay for only a year.

CBP has had to rebuild its internal affairs capability, but it is still far below what is needed.

Though the Trump administration has modestly increased the number of immigration judges, it has adamantly refused to do more. Hiring judges alone won’t solve the problem, though. U.S. immigration courts are not independent, they are part of the executive branch Department of Justice, and judges answer to Attorney General William Barr. A hiring spree now could result in the addition of hundreds of judges who fit the Trump administration’s hardline anti-immigrant political profile, risking grave due process violations for people with strong and valid asylum and protection claims. That is why the American Bar Association, American Immigration Lawyers’ Association, and the National Association of Immigration Judges, among others, recommend moving the immigration courts out of the executive branch and making them independent “Article 1” (of the Constitution) courts established by Congress, similar to the U.S. Tax Court.

Even if the Flores court settlement didn’t prohibit detaining families and children, the practice would still be grossly inappropriate and cruel, as experts ranging from the American Academy of Pediatrics to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights have pointed out. It is also costly: ICE reported to Congress that family detention will cost $295.94 per family per day in 2020, down (for unclear reasons) from $318.79 in 2019. It is unnecessary, too, as experience has shown that asylum seekers can be kept “in the system,” and avoid falling through the cracks, through cost-effective monitoring programs.

Programs that involve caseworkers keeping in frequent touch with asylum-seeking families have brought very high compliance rates for a small fraction of the cost. For $36 per day, an ICE-run Family Case Management Program was achieving a 99 percent compliance rate as a pilot project, with no need for ankle bracelets, until the Trump administration terminated it in 2017.

Evaluating this experience, making any modifications to a revived program, and expanding it across the country makes so much more sense than simply slapping ankle monitors on mothers and dropping them off at bus stations—much less filling Mexican border cities with thousands of homeless, vulnerable families.

Alternatives to detention should also be vastly expanded to include most single adult asylum seekers. Caseworkers are far cheaper than private prisons.

Hardly a week goes by without revelations of Border Patrol, CBP, or ICE personnel engaging in cruel behavior. Just in the past two weeks, we’ve heard allegations of Border Patrol agents forcing unaccompanied children to sleep on concrete cell floors as punishment; allegations of sexual abuse in custody; and revolting hate speech on a Facebook group followed by 9,000 active and former agents.

Agents who engage in this behavior are doing a severe disservice to their agency, and to their colleagues who are trying, with little credit, to do the right thing under awful circumstances. This is a failure of management, which has exhibited little creativity, poor transparency, a failure to be proactive in the face of abuse allegations, and an inability to adjust to today’s vastly changed migrant profile. Management has failed to counter—and in some cases could be fostering—the extremist views of a few members of the Trump administration, whose constant anti-immigrant messages, dispersed through right-wing media, foster some agents’ worst impulses. That is absolutely incompatible with law enforcement.

In 2015, a Department of Homeland Security Integrity Review panel noted that when CBP was created, in 2003, it had “no internal affairs investigators. CBP has had to rebuild its internal affairs capability, but it is still far below what is needed. Currently, CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs is woefully understaffed. CBP has approximately 218 Internal Affairs investigators for a workforce of nearly 60,000 employees, 44,000 of whom are law enforcement officers.” This situation has since improved modestly, but CBP is far from receiving the internal and external oversight that would normally be expected of a law-enforcement agency of its size and sensitive mission.