On February 9, the Obama administration submitted its fiscal year 2017 foreign aid budget request, which for the second consecutive year includes substantial assistance for Central America, primarily for the countries of the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras). Last year, the administration’s fiscal year 2016 budget included a historic US$1 billion aid request to help Central American governments address the pervasive violence, weak governance, and lack of economic opportunity driving migration from the region. This year’s slightly more modest request mirrors the $750 million Congress finally approved in December, which more than doubled the level of assistance to Central America and included strong conditions on strengthening institutions, combating corruption and impunity, and protecting human rights.

Overall, the request sends a strong signal of the United States’ long-term commitment to helping Central America address the underlying factors fueling insecurity, impeding development, and causing many children, families, and individuals in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to leave home. Its success or failure, however, will be determined by the strategy behind the assistance, and the commitment and willingness of the governments of Central American to hold up their end of the bargain.

What’s in the Aid Request for Central America?

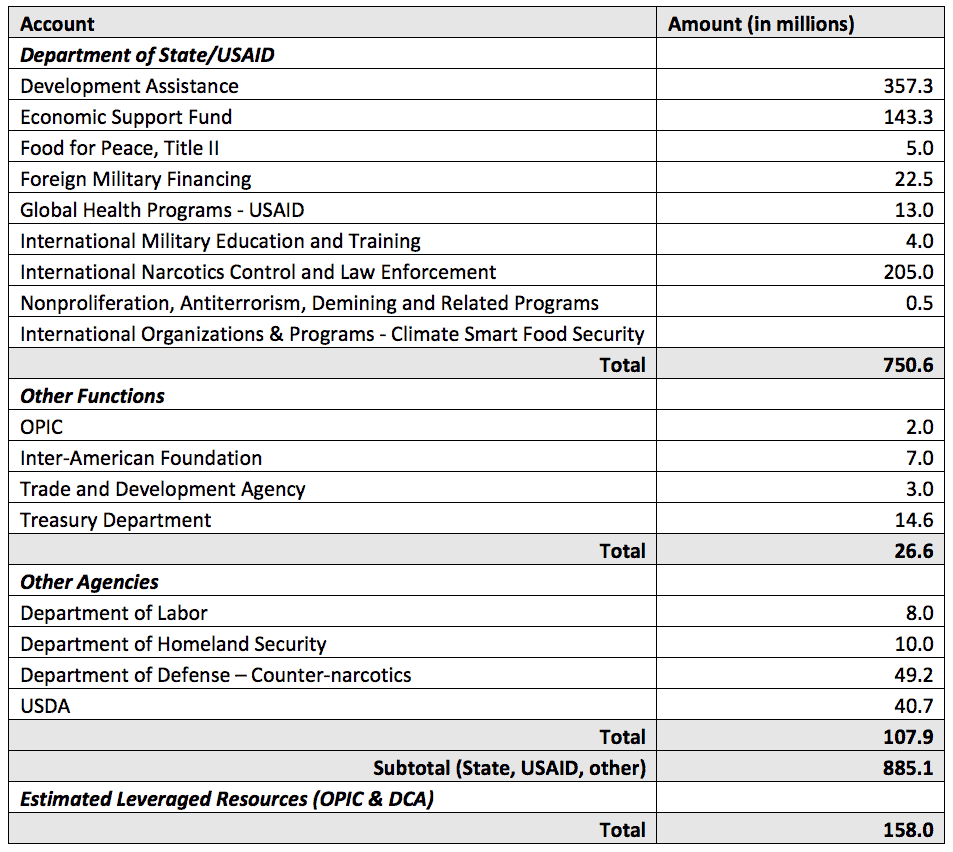

According to the State Department, this year’s aid request includes $750.6 million for the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) “as part of the Administration’s $1 billion investment to further support the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.” From the information WOLA has been able to gather, the overall budget includes the US$750.6 million for the State Department and USAID, $49 million for the Department of Defense (DOD), $40.7 million for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and additional support for various smaller accounts. The administration also requested $2 million for the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) to incentivize private sector investment. Thus, the amount requested for Central America is in reality closer to $885 million (the administration estimates that a modest investment in OPIC and DCA will leverage additional private resources, bringing the total that benefits the region to just over a billion dollars).

Overall, the request demonstrates that the administration is serious about tackling the challenges facing the region. Moreover, the request maintains high levels of funding for State and USAID to support a comprehensive agenda that goes beyond the security-heavy approaches of the past and instead invests in governance and economic development. Within the funds requested for State and USAID, about 67 percent is for Development Assistance (DA) and Economic Support Funds (ESF), and only 27 percent is for International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) programs. Some ESF funding will be channeled through the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), thus shifting the percentages somewhat. Still, these figures imply a greater emphasis on development and strengthening Central American institutions, rather than a solely security focus.

Smart Investments Are Key to Aid Effectiveness

As WOLA emphasized last February, spending alone is not enough. Ultimately, the details and implementation of U.S. assistance will determine whether the new strategy is effective in addressing dire conditions in Central America. The multi-year spending plans that the State Department still needs to submit to Congress for last year’s assistance will reveal whether these funds are being strategically targeted and wisely invested. Better information on the specific objectives, aid levels, and programs in each country, as well as progress indicators being used and how outcomes are being defined, will allow for greater ability to assess whether or not U.S. assistance is achieving the desired results.

As Congress looks at the administration’s fiscal year 2017 request for Central America, along with the fiscal year 2016 spending plan, it should consider several factors:

1. Sufficient attention should be given to expanding evidence-based, community-level programs to reduce youth crime and violence, reintegrate youth seeking to leave the influence of street gangs and criminal groups, and protect children who have suffered violence. Evidence suggests that investing in prevention initiatives that bring together local community groups, churches, police, social services, and government agencies can make a real difference in reducing youth violence and victimization.

2. Development assistance should include a significant investment on job creation, training, and education in order to create new opportunities for youth. Youth with few viable opportunities to study and work are particularly at risk of gang recruitment and irregular migration.

3. Robust programs to enhance transparency and accountability and address the deep-seated corruption that hinders citizens’ access to basic services, weakens state institutions, and erodes the foundations of democracy must be supported. International anti-impunity commissions with the capacity to carry out independent investigations, such as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala, CICIG), can play a crucial role in tackling corruption and organized crime and building domestic investigative capacities.

4. Security-related funding should focus on strengthening civilian law enforcement and justice institutions and making these institutions more accountable and transparent. Programming should be directed toward bolstering policing capacity overall (such as internal and external control mechanisms, police investigation techniques, recruitment and training, etc.), rather than targeting resources to specialized vetted units and other programs that have little impact on improving broader law enforcement institutions. Attention should also be given to strengthening the independence and capabilities of prosecutors and judges. Indicators of success should include measures of progress on these institutional issues.

The 2017 aid request includes considerable DOD funding for counter-drug operations and border security. This funding is expected to support aerial and maritime interdiction capabilities, building partnership capacity, and increasing detection and monitoring of illicit trafficking in Central America. Troublingly, it will also support military and law enforcement units engaged in public security operations. Resources could be better invested in supporting community-based violence prevention programs, judicial and police reforms, combating corruption, and similar needs, rather than on building the capacities of Central America’s militaries, whose internal security roles are expanding while they continue to avoid accountability for past and present human rights abuses and corruption.

Aid Should be Tied to Strong Conditions

Finally, to be truly effective, the aid package should be accompanied by careful monitoring and a continuation of the conditions that Congress wisely put on the 2016 Central America aid package. Weak institutions, endemic corruption, and widespread impunity are major factors behind the high levels of violence and insecurity in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. To varying degrees, the region’s justice and law enforcement institutions are weak, unaccountable, and corrupt. The majority of police forces are underfunded, plagued by poor leadership, and sometimes complicit in criminal activity. Substantial evidence shows that police and criminal justice institutions have been infiltrated and captured by organized criminal groups. Recent efforts to purge and reform police forces have made limited progress, and impunity remains the norm in all three countries.

The fragility of the region’s institutions underscore the need to ensure that the governments of Central America have clear plans with a budget and timeframe for building professional, accountable, and effective public institutions. Conditioning funds on these countries’ demonstrable progress in increasing transparency and accountability, combating corruption in public institutions and agencies, building professional law enforcement and criminal justice institutions, and reducing poverty will ensure that U.S. aid is well spent and is effectively addressing the drivers of irregular migration.

Conclusions

The second year of increased assistance to Central America signals that the United States is committed to addressing the root causes that have made the region one of the most violent in the world. Wise investments, strategic spending plans, and a focus on institutional reforms, combating corruption and impunity, and generating employment and education opportunities for youth are essential as Congress examines the administration’s aid request for the region. Similarly, U.S. assistance will not have the desired impact unless the governments of Central America demonstrate a firm commitment to strengthening the rule of law and to addressing corruption, poverty, and inequality. Finally, as the United States works to implement last year’s aid amounts, and looks ahead to this year’s spending bill, every effort should be made to actively engage local civil society and to develop clear metrics to measure and evaluate results.