In 2016, Central American military and police forces will receive more U.S. assistance than they have in over a decade.

This increase comes as the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador are ramping up drug interdiction and border security efforts, and deploying security forces—often trained in military combat tactics—onto the streets to respond to high murder and crime rates. These heavy-handed policies have generated serious concerns and allegations of excessive use-of-force and extrajudicial executions. They raise questions about whether the United States has truly broken with its history of supporting unaccountable security forces in Central America, and whether these strategies can really keep populations safe or prevent drugs from reaching U.S. streets.

For this year, Congress included well over US$100 million for military, counternarcotics, and border enforcement assistance for Central America. Congress gave the administration over $30 million more than it had requested.

Generally, this money will go toward training, equipment, intelligence, construction at military and police bases, task forces, vetted units, and other facets of illicit trafficking detection and monitoring. A portion will also support military and police units engaged in public security, including support from U.S. Special Operations Forces. While some is funded through the State Department’s aid and counter-drug accounts, much is provided through the Defense Department’s counter-drug budget and delivered by U.S. Southern Command (Southcom), the combatant command responsible for U.S. military operations in Latin America and the Caribbean. A recent investigative article in Politico explains the importance, for accountability and for foreign policy decision-making, of this distinction between State and Defense programs.

WOLA is piecing together what the public can know about the U.S. military’s role in the region and consistently requesting information. The following still-incomplete list details the security force units receiving U.S. support, a rundown of the types of assistance that these units receive, and the questions raised about U.S. security policy in Central America.

Units Known To Be Receiving U.S. Support in Central America’s Northern Triangle

(This is an ongoing list, and WOLA will add to it as necessary.)

El Salvador

Joint Task Force “Grupo Cuscatlán”:

According to the State Department’s 2016 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report:

Joint Interagency Task Force ‘Grupo Conjunto Cuscatlán’ (GCC) composed of PNC [El Salvador’s National Civilian Police], customs and port authorities, and military was established in 2012 to combat transnational organized crime. In 2015, an embedded advisor was added to the Task Force to improve integration. While GCC has shown promise, the unit lacks a government decree assigning specific responsibilities for the administration of, fiscal appropriation to, provision of intelligence to, and maintenance of the unit.

A notice from the Salvadoran government states that the United States invested US$1.78 million to construct a new complex of buildings for GCC in 2015, including lodging for police and a maintenance building. A 2013 article indicates that the group has been involved with Operation Martillo, Southern Command’s main maritime drug interdiction initiative along Central America’s coasts.

El Salvador Army Intelligence Battalion:

In last year’s annual “posture” hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee, then-commander of Southcom Gen. John Kelly noted, “U.S. Army South (ARSOUTH) conducted numerous Countering Transnational Organized Crime (CTOC) training sessions with the El Salvador Army Intelligence Battalion.” There is no other public information available about support to this unit, which does not appear in the 2016 Southcom Posture Statement.

Hacha Command:

Part of the Salvadoran Armed Forces Special Operations Group, in 2013 the Hacha (axe) command trained in the United States to advise police in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to a 2015 article by Southcom’s digital magazine Diálogo. There is little to no other public information about U.S. support of this unit, which is now one of the key units used for public security in El Salvador.

Zeus Command:

This military force is another key unit in the Salvadoran military’s domestic fight against the gangs. Made up of 2,821 members, the Zeus Command is divided into nine task forces and patrols with police in 42 of El Salvador’s most violent municipalities. According to interviews, the United States supports some of its operations. It is unclear if this assistance comes in the form of training, intelligence, or operational support, as there is no public information available about U.S. Southern Command’s role. According to a Wall Street Journal article, U.S. Special Forces and Navy SEALs train security forces in El Salvador, however there are no public details about this training or if it applies to the Zeus Command.

In April 2016, Southcom’s new commander Adm. Kurt W. Tidd “reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to continue working ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with the Salvadoran Armed Forces (FAES) in the fight against the violence generated by gangs and narco-trafficking,” according to Diálogo. The article contained little other information about what that support looks like.

It is unclear if the United States supports the Águila or Trueno commands, whose sole mission is to combat the gangs. Both commands conduct home raids to “ensure to that no one is hiding illegal weapons or drugs,” according to a 2016 Southcom article. The security blog War on the Rocks reported that the Trueno Command is “supported by helicopters and ground vehicles, for situations requiring an armed response beyond that available from local military and police forces.” It is also unknown if any support is given to the army’s San Carlos counternarcotics commands, Los Halcones, an elite police unit, or the New Reaction Special Forces, an elite army unit, all of which were created to fight the gangs.

Border security: It is unclear which units the United States is consistently supporting at El Salvador’s borders. According to a 2016 Southcom article, the United States has given some vehicles to the Sumpul Command, which has 1,000 troops along the border. Southcom Commander Admiral Tidd noted before the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2016 that U.S. Army South has conducted Countering Transnational Organized Crime (CTOC) CTOC trainings focused on patrolling the border. Through interviews, WOLA also learned that the Georgia National Guard will be helping El Salvador with its border security efforts this year. All other public information about U.S. support for El Salvador’s border security is related to State Department-funded initiatives and discussed below.

Counternarcotics: In addition to participating in Operation Martillo, U.S. Southern Command’s joint multinational drug interdiction effort in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean near Central America, El Salvador’s military also operates alongside the United States at a Cooperative Security Location, based alongside El Salvador’s busiest airport, Comalapa International Airport in San Salvador, where “U.S. detection and monitoring aircraft fly missions to detect, monitor and track aircraft or vessels engaged in illicit drug trafficking.”

Other engagement: Aside from supporting specialized units, there are a number of ongoing engagement exercises between U.S. Southern Command and partner militaries in Central America. Here are just a few examples:

-

- “Marine Corps Forces South (MARFORSOUTH) delivered tailor-made training to our partners by establishing persistent presence security cooperation teams in Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. This was training often conducted hand-in-hand with our Colombian Marine Corps partners through the U.S./Colombia Action Plan,” according to Admiral Tidd’s 2016 posture statement.

-

- Special-Purpose Marine, Air, and Ground Task Force (SPMAGTF):Made up of Marine Reservists, this 280-strong force was deployed to Honduras for six months last year, with at least 90 troops visiting Guatemala, El Salvador, and Belize, “to help partner nations extend state presence and security.”

-

- The United States invested $1.3 million in the Salvadoran military’s Peace Operations Center (CEOPAZ), funded through the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI) account, managed by Southern Command and the U.S. Embassy in El Salvador. This initiative intends to strengthen El Salvador’s “contributions to the UN and highlight the country’s increasing role in peacekeeping operations worldwide.”

Honduras

Naval Special Forces (Fuerzas Especiales Navales, FEN): This force is primarily concerned with counternarcotics operations. Joint Task Force Bravo (JTF-Bravo), a unit of about 500 U.S. military personnel based at the Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras, participates in operations with, and trains, the FEN. As it is the largest presence of U.S. troops in the region, JTF-Bravo supports operations throughout Central America. MARFORSOUTH is also currently training members of the Honduran Naval Force (Fuerza Naval de Honduras, FNH) on “combating drug trafficking and urban operations.”

Special Response Team and Intelligence Troop (Tropa de Inteligencia y Grupos de Respuesta Especial de Seguridad, TIGRES): This SWAT-style militarized police unit, known as the “Tigers,” was created in 2014 as part of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández’s crackdown to address the country’s high levels of violence. President Hernández has since made good on his pledge to deploy soldiers and militarized police units throughout the country’s most violent areas.

As a recent Wall Street Journal (WSJ) report noted, “Over the past two years, U.S. Special Forces have built the elite SWAT unit, called the Tigres, from scratch.” Colombian counterparts have also helped to stand up and train this unit. As explained in the article, during operations Honduran agents are the ones who “kick in doors” and carry out arrests, while U.S. Special Forces monitor operations from apartments or similar nearby locations. The forces “marked assault routes on a satellite view of the slum and scanned photos from a circling police helicopter. They read WhatsApp text messages between the SWAT commander and his men.” Green Berets train the Tigres at an isolated base in the mountains, but the United States does not provide the force with weapons: only uniforms, boots, radios, navigational tools, and training ammunition. All of this information came from the WSJ investigation.

National Interagency Security Force (Fuerza Nacional de Seguridad Interinstitutional, FUSINA): Created by President Juan Orlando Hernández in February 2014, FUSINA is an inter-agency task force made up of members of the police, the military, the Attorney General’s Office, and intelligence agencies. It is led by the Honduran military and is tasked with fighting organized crime. According to a February 2016 Southern Command article, “The security force maintains a strong and constant presence in 115 communities with high levels of delinquency provoked by gangs. It carries out motorized and foot patrols to identify and capture members of such groups. Additionally, it has launched an education program in schools around the country with the purpose of training children and teens to resist getting involved with gangs.” The force also conducts operations along the Honduran-Guatemalan border.

In an August 2015 letter to Secretary of State John Kerry, 21 members of Congress expressed concern over the Honduran military’s involvement in public security and increasing U.S. military assistance to the country, specifically mentioning FUSINA. They wrote: “We are concerned about Honduran media reports that in mid-May of this year, a team of 300 U.S. military and civilian personnel, including Marines and the FBI, conducted ‘rapid response’ training with 500 FUSINA agents, using U.S. helicopters and planes, despite allegations regarding the agency’s repeated involvement in human-rights violations.” There is little other publicly available information about U.S. support for FUSINA.

Border security: Although some members of the Tigres are stationed along Honduras’ borders, they are not the main presence there. Rather, in these zones are members of an elite unit of Honduras’ National Police, which has been funded by the U.S. State Department and trained by U.S. Border Patrol, members of the Military Police of Public Order (Policía Militar del Orden Público, PMOP), a new military branch that the United States has said it does not support, and other units of the Honduran military that have been trained by U.S. units, including the Texas National Guard.

Nearly all other public information about U.S. support for El Salvador’s and Honduras’s border security discusses initiatives funded through the State Department and overseen by State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), as well as Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the Department of Homeland Security. Nearly all CBP and ICE assistance is funded by INL.

Some examples include:

- CBP is working with INL “to place nine CBP Advisors throughout Central America to provide capacity building and technical assistance for border control officials to more effectively address migration issues in-country,” according to testimony from Ronald Vitiello, Acting Chief of U.S. Border Patrol.

- “To promote investigative capacity-building and anti-smuggling efforts, DHS, with DOS funding, will increase the presence of the Transnational Criminal Investigative Units (TCIUs), which are sponsored by U.S. Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) in Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Panama,” according a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report. TCIUs are specialized, vetted units that work with national police forces, customs officers, immigration officers, and prosecutors. They were created to “to enhance transnational efforts against all forms of illicit trafficking with a particular focus on human smuggling.” There are currently nine TCIU units with more than 250 foreign law enforcement officers, according to a March 2016 testimony from Lev J. Kubiak, Assistant Director of International Operations for Homeland Security Investigations, an investigative arm within ICE in the DHS.

The Defense Department and CBP also support some TCIU investigations. Between 2012 and 2014, DHS spent $2.4 million of its own funding supporting units in the Northern Triangle. In 2014, TCIUs, which until then had only been present in Guatemala, were expanded to El Salvador and Honduras. Because Congress provided additional funding for TCIUs in 2015, ICE expanded units in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia, and reestablished an additional TCIU in Mexico.

- “DHS also plans to expand a model of border-focused vetted units, such as the Special Tactics Operations Group or Grupo de Operaciones Especiales Tacticas (GOET) in Honduras, to El Salvador and Guatemala in partnership with CBP. Through those vetted units, DHS provides training and capacity building to foreign counterparts, empowering them to investigate, identify, disrupt, and dismantle transnational criminal organizations that are engaging in illicit activities in the host country,” according to the same GAO report.

Guatemala

Interagency Task Force Tecún Umán (IATF-Tecún Umán): This unit, located near the Mexico-Guatemala border, was established in July 2013 to interdict drugs flowing across Mexico’s southern border and combat organized crime in the area. Based in Coatepeque in the state of Quezaltenango, the force is made up of members of Guatemala’s army, national police, and Attorney General’s Office. Southern Command and U.S. Army South have identified the force as one of their top priorities in Central America. U.S. Army South, soldiers from the Texas National Guard, U.S. Border Patrol, and the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) have all trained members of this task force.

The United States has contributed over $22.5 million to IATF-Tecún Umán, over $15 million of which has come from Southern Command. In November 2014, the Rand Corporation published a federally-funded evaluation report about the force that pointed to several shortcomings, including, but not limited to, undefined roles and relationships between the military and police, a lack of results, and “not being used for the mission it was designed to execute.”

Interagency Task Force Maya Chortí (IATF-Chortí): Border interdiction unit Maya Chortí was stood up in March 2015 on the Honduran-Guatemalan border as part of an agreement between Honduras and Guatemala. Based on IATF-Tecún Umán, it is the second of Guatemala’s four interagency task forces. Honduran security forces also participate in the task force. Each country reportedly provides 200 police and 190 soldiers. Guatemalan officials have said that it “mirrors a border security agreement that the [United States] has with Mexico,” which is odd because no such joint coordination exists between the Unites States and Mexico.

According to the State Department,“IATF-Chorti includes police, military, customs, and immigration officials, and will complement the IATF-Tecun Uman on the Guatemalan-Mexican Border.” Southcom has so far pledged $13.4 million to assist in initial development, according to RAND.

Interagency Task Force Xinca (IATF-Xinca): Covering five departments largely along Guatemala’s border with El Salvador, IATF-Xinca is the fourth interagency task force created by the Guatemalan government, after Tecún Umán, Chorti, and Kaminal, another task force created in 2012 comprised of 280 members of the police and military present in the Villa Nueva and Guatemala municipalities. RAND reported in 2015 that Southcom was planning to apply the model of Tecún Umán to other task forces, although the extent of its involvement in this task force, which was just created in January 2016, is unclear.

Los Halcones (Hawks): This elite unit is part of the Guatemalan National Civil Police’s (Policía Nacional Civil, PNC) Anti-narcotics Interdiction and Anti-terrorist Force (Fuerza de Tarea de Interdicción Aérea, Antinarcótica y Antiterrorista, FIAAT). According to Southern Command’s Diálogo, “For more than six weeks, 22 agents from the Guatemalan National Civil Police’s (PNC) “Los Halcones” (Hawks) unit trained with United States Army Green Berets, participating in exercises focusing on fighting criminal organizations, including drug-trafficking groups that use the Central American country as a transshipment point to transport narcotics into North America.” About 60 other agents participated in rapid shock trainings against drug traffickers.

Kaibiles: The United States has built a cozy relationship with the Kaibiles, Guatemala’s special operations force, and their training academy. According to a 2013 U.S. Special Operations Command South news release, “The Kaibil School is considered one of the most prestigious, vigorous, arduous military courses in Central America… Their motto: ‘If I advance, follow me. If I stop, urge me on. If I retreat, kill me.’” In 2013, an American soldier graduated from the Kaibil School for the first time in 25 years. As WOLA Senior Associate Adam Isacson has explained, the Kaibiles have a historic reputation for brutal, violent training tactics, which in the past included “killing animals and then eating them raw and drinking their blood in order to demonstrate courage,” according to Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification report. The Kaibiles were one of the most notorious units for carrying out atrocities against the population during the country’s civil war.

Special Interdiction and Rescue Group (Grupo Especial de Interdicción y Rescate, GEIR): As this 2015 Special Operations Command South article reported, “The GEIR is considered to be Guatemala’s top fighting force.” Kaibiles are often assigned to the unit, which is “charged to neutralize, prevent, and act against any narcoterrorism threat in the country. With support from “Green Berets” assigned to the U.S. 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne), the mission of GEIR, is simple: Keep Guatemala safe for its people.” The U.S. Special Forces regularly work with GEIR members “in close quarters combat, weapons familiarization, sniper techniques, medical care, and communications just to name a few.”

Naval Special Forces (Fuerzas Especiales Navales, FEN): According a 2015 statement during an appearance by then-Southcom Commander General Kelly at the Atlantic Council, a D.C.-based think tank, the United States has supported this drug interdiction unit, primarily providing intelligence. They have also carried out operations and trainings together, according to a 2013 press release.

Types of U.S. Assistance to Central America, and the Questions They Raise

The above list provides what details we have found about the U.S. relationship with Central American militaries. These gaps should be filled in. But more than what specific units are being supported and how, there are also broader questions about U.S. military engagement with Central American security forces.

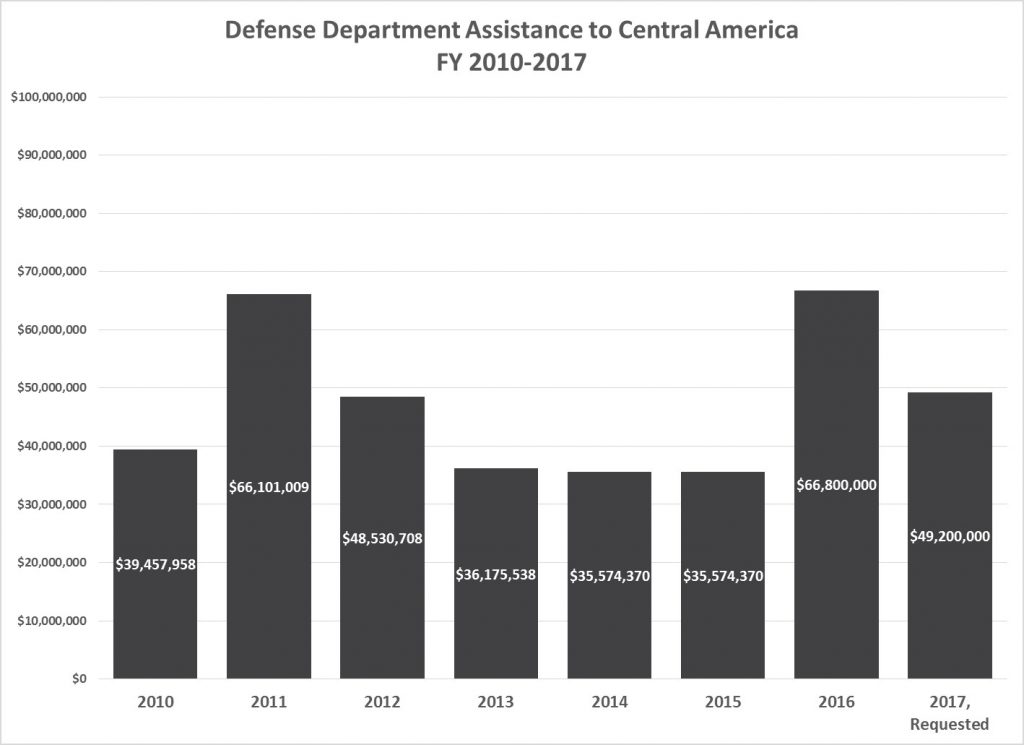

The over US$100 million for military, counternarcotics, and border enforcement assistance includes nearly $67 million that Congress set aside for the Defense Department’s counter-drug budget. This amount is in addition to the $750 million aid package for Central America approved for fiscal year 2016. Within that $750 million are $30 million in military aid programs executed by the Defense Department, and an undisclosed amount that will be going to security forces through the State Department’s International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) program, which funds both military and economic assistance. Overall, the total U.S. support for security force units is likely considerably higher than $100 million, but without more publicly available information, it is impossible to report an exact number.

From the information available, it appears that Southcom delivers three main types of assistance:

1. Border and maritime security: This includes activities such as engagement exercises with partner nation militaries, maritime trainings, interdiction operations, and providing support to border task forces. While guarding coasts and borders may be a more appropriate role for small-country militaries, it still raises questions:

Border security mandates: Even if their mission is principally to combat organized crime and stop drugs, units with border security responsibilities are inevitably encountering the massive current flow of migrants, especially families and unaccompanied children, fleeing the Northern Triangle. What happens when they encounter them? Do they send them back to the communities from which they fled, where they may face targeted threats to their lives? Does the training these units receive from the United States include protocols for interacting with individuals who have protection concerns? Meanwhile, drug traffickers, human smugglers, and other organized-crime operators aggressively seek to corrupt security-force personnel at borders. Do the units receiving U.S. assistance have credible internal affairs units, whistleblower protections, complaint lines, and other mechanisms to root out corruption?

Drug interdiction: Central America is the main drug trafficking corridor in the Western Hemisphere. According to the State Department’s most recent International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, 90 percent of drugs that reach the United States first travel through the isthmus. At the same time, the current high levels of murder and gang violence, particularly in El Salvador, are not necessarily associated with transnational drug trafficking. While the region’s gangs do engage in neighborhood micro-trafficking, there is no evidence that seizing more tons of drugs brings down crime or violence in these countries, or reduces overall drug consumption in the United States.

2. Training militarized police engaged in citizen security: Publicly, Southcom says that it does not support military units engaged in public security. Rather, that mission is up to State Department-managed police programs, while Southcom’s military aid prefers to focus on coasts, rivers, and borders. Nonetheless, Southcom does train and support elite police units that carry military-style weapons and learn military-style tactics in all three Northern Triangle countries. While supporting these civilian units is theoretically preferred over supporting military units to work as police, their deployment carries similar human rights concerns. In Central America these units are trained by U.S. Special Operations Forces, and in a country like Honduras, where the Security Minister is a former army general, the line between police (protecting a population with minimal violence) and military (defeating an enemy with maximum violence) can become blurred beyond recognition.

3. Supporting militaries engaged in citizen security: As they struggle with weak public institutions, pervasive impunity, and astronomically high violent crime rates,Central American governments have expanded the role of their armed forces in public security, without presenting plans to take them off the streets. While there is little evidence that this approach alone will bring down homicide rates, especially in the long term, there is mounting evidence that it escalates tensions with citizens and can even exacerbate violence. The strategy also carries significant human rights concerns and in many countries, particularly El Salvador, there are increasing reports of abuses at the hands of soldiers and militarized police deployed to the streets.

As WOLA Senior Associate for Citizen Security Adriana Beltrán recently noted,

“Resources could be better invested in supporting community-based violence prevention programs, judicial and police reforms, combating corruption, and similar needs, rather than on building the capacities of Central America’s militaries, whose internal security roles are expanding while they continue to avoid accountability for past and present human rights abuses and corruption.”