GUATEMALA / Areas of progress

4.1

National Law in Accordance with International Standards

Between 2014 and 2017, justice sector institutions made commendable efforts and Congress advanced legislative reforms. These marked important institutional reforms and helped to strengthen internal regulations and align them with international standards. The Public Prosecutor’s office made important advances, such as strengthening the Analysis Unit, the adoption of new divisions among prosecutors’ offices, and the use of wiretapping, among other tools, which contributed to dismantling numerous criminal structures at the national level.

GUATEMALA / Areas of progress

4.2

Investigative capacity and prosecution of criminal networks and organized crime

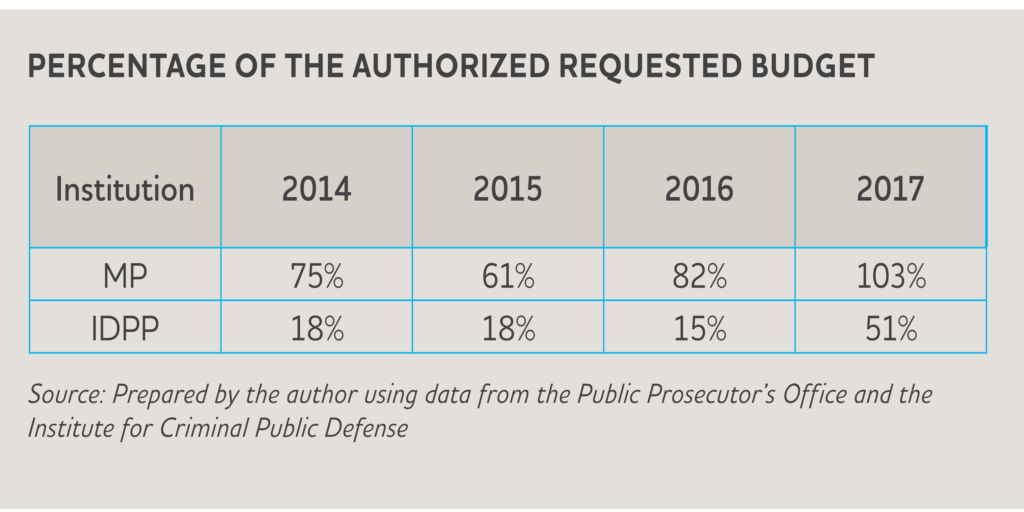

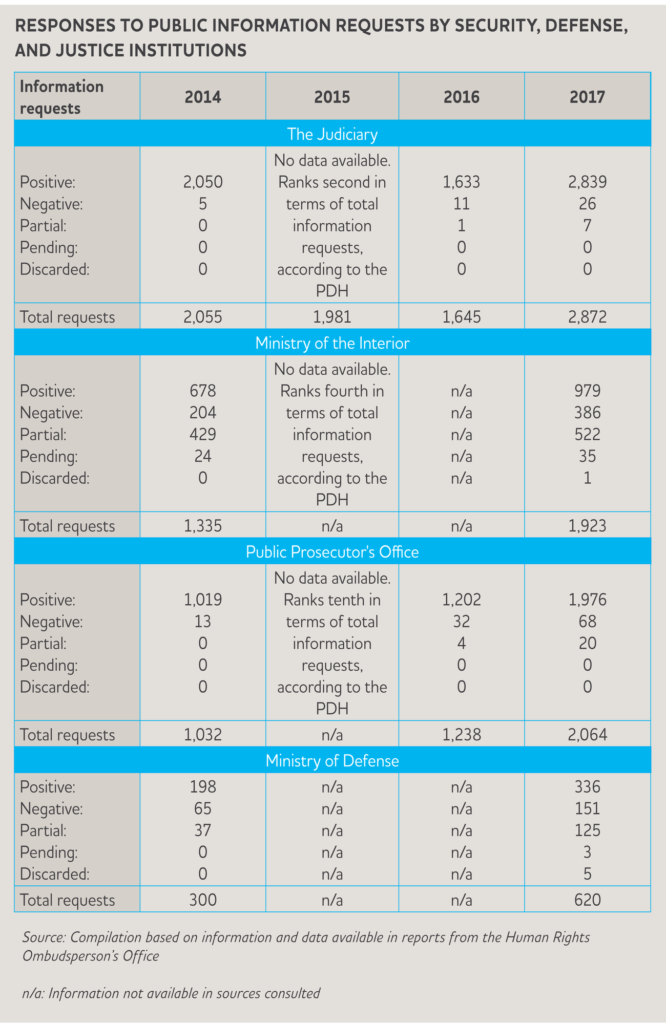

The Public Prosecutor’s Office has various prosecutors’ offices and specialized units to address the investigation and criminal prosecution of violence and organized crime activities. Among these specialized prosecutors’ offices are the offices against organized crime, drug-related crimes, money or asset laundering, extortion, human trafficking, kidnapping, crimes against life, and femicide, among others. The Public Prosecutor’s Office denied information requests regarding the number of personnel assigned to these offices. Financial data shows that, of these prosecutors’ offices and special units that provided budget information, they received 8.4 percent of the total budget allocated to the Public Prosecutor’s Office during the period analyzed. Additionally, there was a trend of an annual increase in the allocated budget, with the exception of the special prosecutors’ offices on organized crime and drug-related crimes, which suffered a reduction in 2015, and the office on money laundering, whose budget also decreased in 2015 and 2017.

In order to better fulfill its functions, the Judiciary implemented specialized criminal courts, such as high risk courts and those that hear of crimes of femicide, violence against women, and crimes of sexual violence, exploitation and human trafficking. These high risk courts and tribunals have been key in fighting violence and organized crime, yet they still lack adequate space and personnel. In the case of femicide and violence against women, the femicide courts and tribunals exist in 50 percent of the country’s departments. However, women from rural regions often do not benefit from these courts’ protection and services as they either don’t have access to the specialized jurisdiction or, in some departments, these bodies are made up entirely of men.

GUATEMALA / Areas of progress

4.3

Effectiveness of Investigations of Criminal Networks and Organized Crime

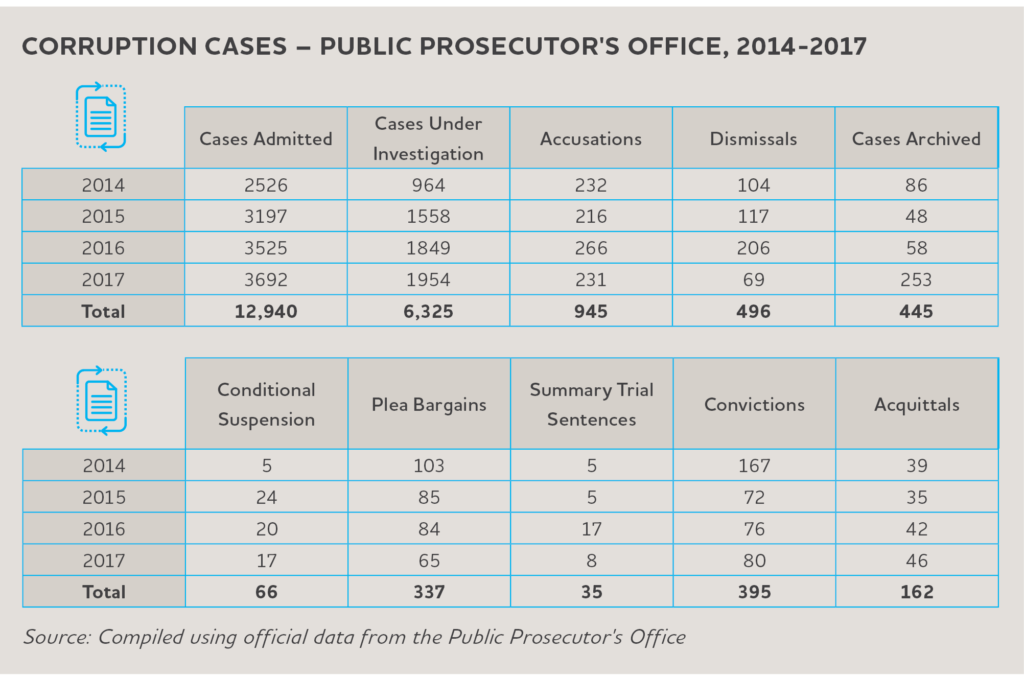

Changes made within the Public Prosecutor’s Office to improve prosecutorial efficiency made way for important advances in strategic criminal prosecution, increasing the operational capacity of investigation processes. Thus, between 2015 and 2016, the office was able to dismantle 93 criminal structures with a total of 716 members.

The gap between the reality of the phenomenon of violence against women and convictions remains quite large. In 2017, at least 57 out of 100,000 women were subjected to femicide or other forms of violence against women. In that same year, of the men indicted by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, only 3 percent were convicted at trial.

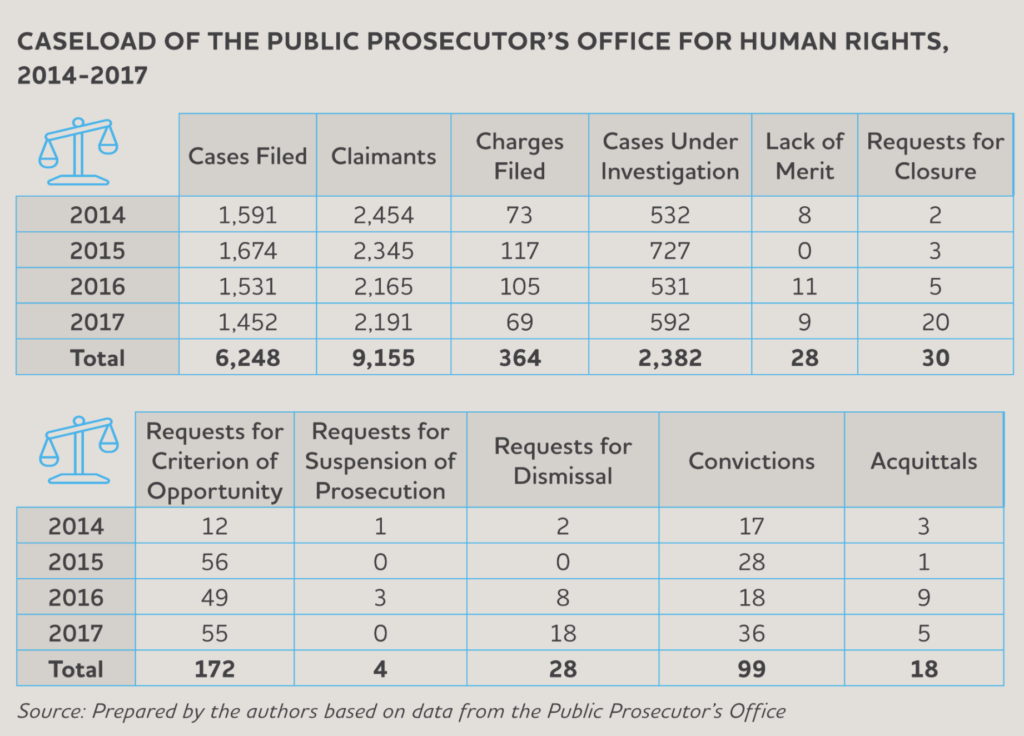

The same gap is evident between the cases filed by special prosecutors’ offices and the number that results in convictions or acquittals. It is important to note that not all of the cases that are filed manage to be prosecuted and lead to a sentence in the same year. In other cases, due to various circumstances, cases may be filed or dismissed or resolved by other means that do not imply reaching an oral or public hearing. At other times, the complexity of the crime results in a prolonged investigation. Nevertheless, the advances of the Public Prosecutor’s Office are closely linked to strengthening the Judiciary, which also affects the prompt decisions of the cases that are admitted.