Limiting the Role of the Armed Forces in Public Security Activities

CENTRAL AMERICA MONITOR:

EVALUATING PROGRESS

Central America’s Northern Triangle region is struggling with violence, corruption and impunity.

Scroll for the key findings or to find links to download the full reports under each area of progress.

Evaluating progress in Central America

As Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras struggle with high levels of violence and insecurity, systemic corruption, and widespread impunity, it’s critical that we find ways to assess how the policies and strategies being implemented in the region are contributing to the strengthening of the rule of law, improving transparency and accountability, and to reducing violence and insecurity. Using a comprehensive series of indicators, the Central American Monitor aims to measure progress and identify trends over time in eight key areas directly relevant to rule of law and security, thus providing critical information that can inform policies and strategic investments in the region.

The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), the Myrna Mack Foundation (FMM) of Guatemala, the University Institute for Public Opinion (Iudop) of the José Simeón Cañas Central American University (UCA) of El Salvador, the University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (IUDPAS) of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) have developed a series of qualitative and quantitative indicators to evaluate progress in Central America in eight key areas.

Limiting the Role of the Armed Forces in Public Security Activities

Areas of progress

1.

Development and Implementation of a Concrete Plan

The Ministry of National Defense denied the majority of public information requests submitted by the Central America Monitor that sought to analyze the size of the military and its participation in public security. The lack of transparency in this area is worrisome as the requests were for basic information and did not include information that could risk national security in any way. This failure to provide information not only prevents a comprehensive analysis of the military and its participation in internal policing, but also represents an alarming trend of opacity when it comes to civic oversight and accountability for possible human rights violations by the military in exercising police functions.

Starting in 2000, successive administrations and the Guatemalan Congress have cited public safety as a reason for enacting laws and agreements that grant a return to the participation of the military in police tasks, in full violation of the 1996 Peace Accords. In total, they adopted 7 agreements and decrees which allowed participation of the military in combating organized crime and common crime, surveilling the perimeters of pre-trial detention centers, prisons and rehabilitation centers, among others; maintaining order and security within jails and prisons; and allowing pursuit and detention of fugitive inmates and the custody of inmates. In addition, they established combined forces between military and police and consolidated coordination mechanisms of the Ministry of National Defense in all matters of internal and external security.

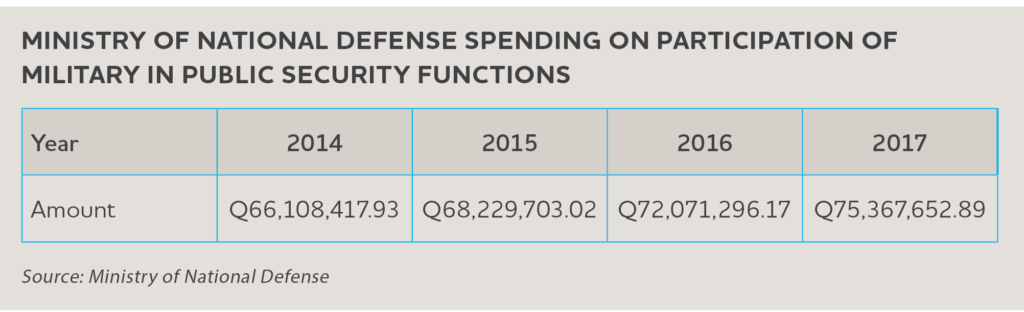

From 2014 to 2017, the army was allocated an average annual budget of Q70,444,267.50 ($9.1 million) to cover military participation in public safety tasks. The allocated amount grew each year, increasing 3.2% between 2014 and 2015, 5.6% between 2015 and 2016 and 4.6% between 2016 and 2017. According to consulted sources, a strong criticism at the time was that the expenses that the Ministry of Defense made in matters of security were paid for by the Ministry of the Interior. At the end of 2016, in the face of a growing social opposition to the militarization of the internal police function and under the leadership of the then Minister of Interior, the government announced a roadmap for the gradual withdrawal of the Guatemalan armed forces in citizen security tasks. The plan sought to completely remove the military from police functions in three distinct phases before the end of 2017. Despite some advances in the plan’s execution––as was the case with decrease of the military (from 30 zones to 11) and the withdrawal of some 2,100 troops––they failed to meet their initial timeline, and a final withdrawal was anticipated for March 2018.

At the end of 2016, in the face of a growing social opposition to the militarization of the internal police function and under the leadership of the then Minister of Interior, the government announced a roadmap for the gradual withdrawal of the Guatemalan armed forces in citizen security tasks. The plan sought to completely remove the military from police functions in three distinct phases before the end of 2017. Despite some advances in the plan’s execution––as was the case with decrease of the military (from 30 zones to 11) and the withdrawal of some 2,100 troops––they failed to meet their initial timeline, and a final withdrawal was anticipated for March 2018.

Starting in 2000, successive administrations and the Guatemalan Congress have cited public safety as a reason for enacting laws and agreements that grant a return to the participation of the military in police tasks, in full violation of the 1996 Peace Accords. In total, they adopted 7 agreements and decrees which allowed participation of the military in combating organized crime and common crime, surveilling the perimeters of pre-trial detention centers, prisons and rehabilitation centers, among others; maintaining order and security within jails and prisons; and allowing pursuit and detention of fugitive inmates and the custody of inmates. In addition, they established combined forces between military and police and consolidated coordination mechanisms of the Ministry of National Defense in all matters of internal and external security.

From 2014 to 2017, the army was allocated an average annual budget of Q70,444,267.50 ($9.1 million) to cover military participation in public safety tasks. The allocated amount grew each year, increasing 3.2% between 2014 and 2015, 5.6% between 2015 and 2016 and 4.6% between 2016 and 2017. According to consulted sources, a strong criticism at the time was that the expenses that the Ministry of Defense made in matters of security were paid for by the Ministry of the Interior.

At the end of 2016, in the face of a growing social opposition to the militarization of the internal police function and under the leadership of the then Minister of Interior, the government announced a roadmap for the gradual withdrawal of the Guatemalan armed forces in citizen security tasks. The plan sought to completely remove the military from police functions in three distinct phases before the end of 2017. Despite some advances in the plan’s execution––as was the case with decrease of the military (from 30 zones to 11) and the withdrawal of some 2,100 troops––they failed to meet their initial timeline, and a final withdrawal was anticipated for March 2018.

At the end of 2016, in the face of a growing social opposition to the militarization of the internal police function and under the leadership of the then Minister of Interior, the government announced a roadmap for the gradual withdrawal of the Guatemalan armed forces in citizen security tasks. The plan sought to completely remove the military from police functions in three distinct phases before the end of 2017. Despite some advances in the plan’s execution––as was the case with decrease of the military (from 30 zones to 11) and the withdrawal of some 2,100 troops––they failed to meet their initial timeline, and a final withdrawal was anticipated for March 2018. Limiting the Role of the Armed Forces in Public Security Activities

Areas of progress

2.

Conduct of Military Forces

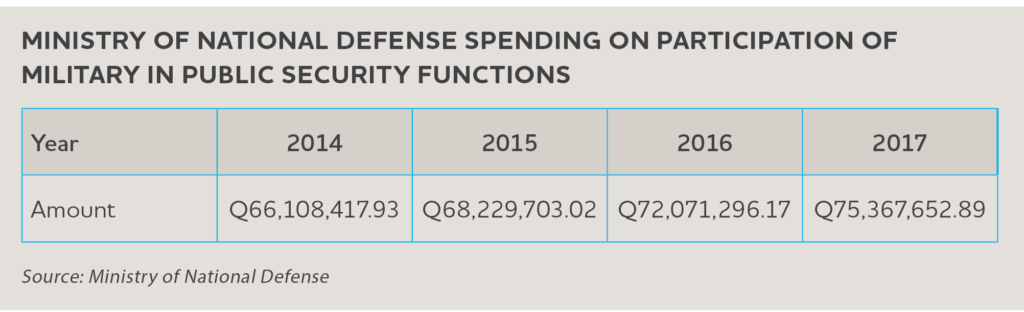

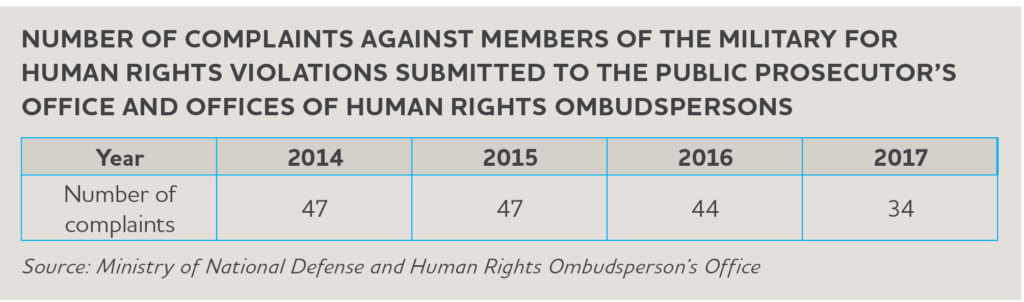

The Human Rights Ombudperson’s Office received 172 legal complaints of human rights violations by the Army, an average of 43 complaints per year. These figures only represent the complaints received by the Ombudsperson’s Office and omit those cases that go unreported; as such, the true number of human rights violations is probably higher.

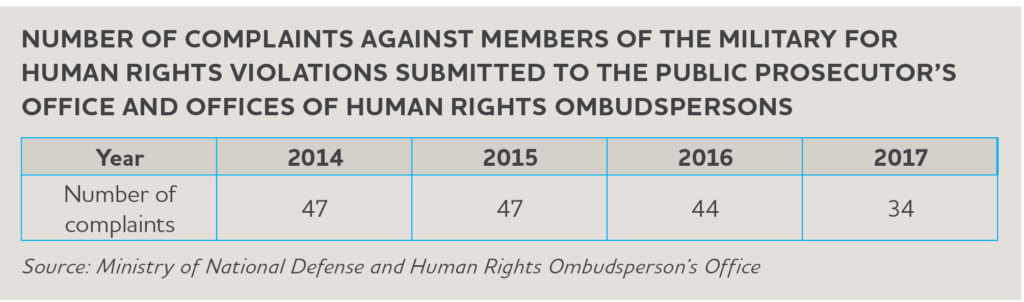

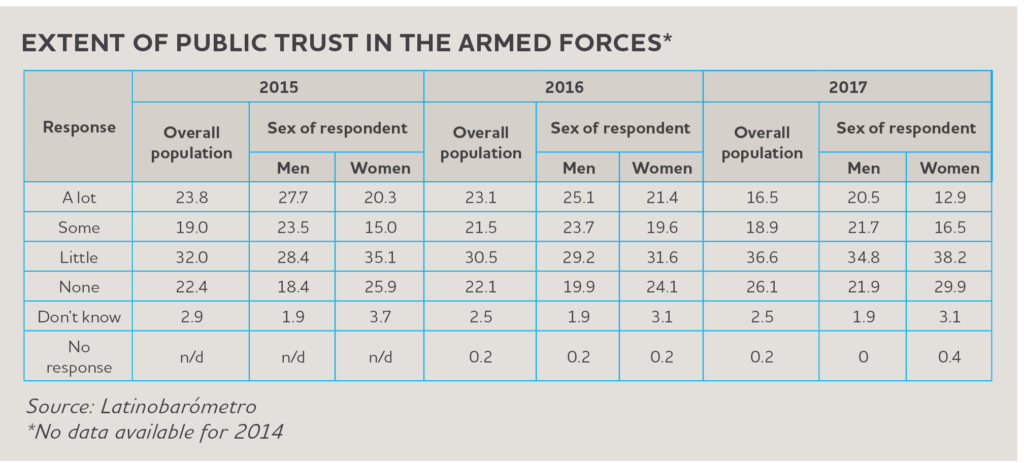

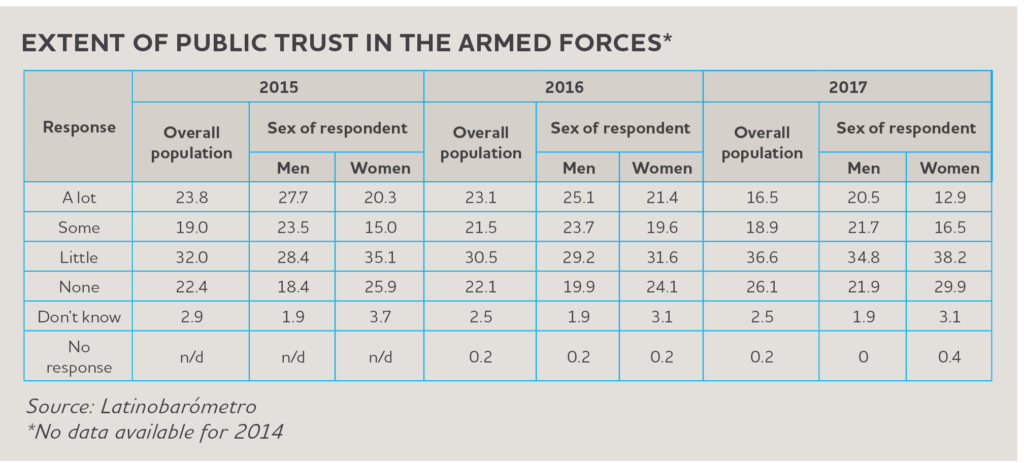

In analyzing the level of public confidence in the Army, public surveys administered between 2015 and 2017 (no data is available for 2014) show little change between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, 42.8 percent of the population expressed great or some trust in the Armed Forces, while 54.4 percent had little or none. In 2016, 44.6 percent reported they had great or some trust, while 52.6 percent had little or none. However, 2017 showed a notable loss of trust in comparison with previous years, with 35.4 percent reporting great or some trust in the Armed Forces and 62.7 percent having little or none. Another important trend is revealed when the data is disaggregated by sex. In the three years under analysis, men reported having greater trust in the Armed Forces than women. For example, in 2017 42.2 percent of men and 29.4 percent of women reported having great or some trust in the Armed Forces, a gap evident in each year.

In analyzing the level of public confidence in the Army, public surveys administered between 2015 and 2017 (no data is available for 2014) show little change between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, 42.8 percent of the population expressed great or some trust in the Armed Forces, while 54.4 percent had little or none. In 2016, 44.6 percent reported they had great or some trust, while 52.6 percent had little or none. However, 2017 showed a notable loss of trust in comparison with previous years, with 35.4 percent reporting great or some trust in the Armed Forces and 62.7 percent having little or none. Another important trend is revealed when the data is disaggregated by sex. In the three years under analysis, men reported having greater trust in the Armed Forces than women. For example, in 2017 42.2 percent of men and 29.4 percent of women reported having great or some trust in the Armed Forces, a gap evident in each year.

In analyzing the level of public confidence in the Army, public surveys administered between 2015 and 2017 (no data is available for 2014) show little change between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, 42.8 percent of the population expressed great or some trust in the Armed Forces, while 54.4 percent had little or none. In 2016, 44.6 percent reported they had great or some trust, while 52.6 percent had little or none. However, 2017 showed a notable loss of trust in comparison with previous years, with 35.4 percent reporting great or some trust in the Armed Forces and 62.7 percent having little or none. Another important trend is revealed when the data is disaggregated by sex. In the three years under analysis, men reported having greater trust in the Armed Forces than women. For example, in 2017 42.2 percent of men and 29.4 percent of women reported having great or some trust in the Armed Forces, a gap evident in each year.

In analyzing the level of public confidence in the Army, public surveys administered between 2015 and 2017 (no data is available for 2014) show little change between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, 42.8 percent of the population expressed great or some trust in the Armed Forces, while 54.4 percent had little or none. In 2016, 44.6 percent reported they had great or some trust, while 52.6 percent had little or none. However, 2017 showed a notable loss of trust in comparison with previous years, with 35.4 percent reporting great or some trust in the Armed Forces and 62.7 percent having little or none. Another important trend is revealed when the data is disaggregated by sex. In the three years under analysis, men reported having greater trust in the Armed Forces than women. For example, in 2017 42.2 percent of men and 29.4 percent of women reported having great or some trust in the Armed Forces, a gap evident in each year.

GLOSSARY

The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), the Myrna Mack Foundation (FMM) of Guatemala, the University Institute for Public Opinion (Iudop) of the José Simeón Cañas Central American University (UCA) of El Salvador, the University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (IUDPAS) of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) have developed a series of indicators to assess the progress in Central America in eight key areas. That progress will reflect both the commitment of Central American governments and the effectiveness of international assistance. The indicators include a combination of quantitative data and qualitative analysis in order to gain a more in-depth understanding of the changes taking place in each country. Data sources include official documents and statistics, surveys, interviews, and reviews of existing laws and regulations that will be systematically compiled.

WOLA, the Myrna Mack Foundation, Iudop, and IUDPAS developed these indicators in a months-long process that included review of international standards, consultation with experts, and consensus among all partners about the key issues to address.

Our goal is to provide an instrument that can help identify the areas of progress and opportunities for improvement shortfalls for of the policies and strategies being implemented on the ground in a form that is useful for policymakers, donors, academics, and the public. At the same time, we hope to provide analysis that can contribute to the evaluation of trends over time both within and between the countries of the Northern Triangle.

1

Strengthening the Capacity and Independence of Justice Systems

Capacity of the Justice System: Number of criminal justice officials, geographical coverage, workload, effectiveness, and public trust.

Internal Independence: Existence and implementation of a public, merit-based selection process free from external influence, a results-based evaluation system, and an effective disciplinary system.

External Independence: Size of budget allocated for the judicial sector and implementation of national and international protection measures for justice officials.

2

Cooperation with Anti-Impunity Commissions

Political Will and Level of Collaboration: Commitment of the state to collaborate and enable the work of the CICIG in Guatemala and the MACCIH in Honduras, demonstrated by the progress of emblematic cases, the approval of legislative reforms, and support for domestic counterparts working with these commissions.

3

Combating Corruption

Level of Public Trust: Degree of public trust in state institutions involved in efforts to prevent, identify, investigate, and punish corruption.

Scope and Implementation of Legislation to Combat Corruption: Classification of new crimes in criminal codes and reforms of existing anti-corruption laws to adhere to international standards.

Advancements in Criminal Investigations: Number of corruption cases filed, prosecuted, and resolved, as well as the progress made in emblematic cases.

Functioning of Oversight Bodies: Existence and capacity of external oversight bodies or agencies to combat corruption.

4

Tackling Violence and Organized Crime

Capacity Building: Existence and functioning of specialized anti-organized crime units, application of scientific and technical investigative methods, and functioning of judges or tribunals dedicated to the prosecution of organized crime

Advances in Criminal Investigations: The number of organized crime-related cases filed, prosecuted, and resolved, as well as the progress made in emblematic cases.

Crime Reduction: Convictions for homicides, extortion, and against criminal networks, as well as a reduction in serious and violent crimes.

5

Strengthening Civilian Police Forces

Functioning of Police Career Systems: Existence and effectiveness of police recruitment and promotion mechanisms, training processes, and disciplinary systems, as well as the structure of police bodies.

Allocation and Use of Budgetary Resources: Allocation and effective use of public funds and percentage designated for the wellbeing of members of the civilian police forces.

Community Relations: Public trust in the police, police-community relations, and relations with indigenous authorities.

6

Limiting the Role of the Armed Forces in Public Security Activities

Development and Implementation of a Concrete Plan: The design and implementation of a publicly accessible and verifiable plan with goals, timelines, activities, and clearly established indicators; repeal of legal norms authorizing participation of armed forces in public security, and access to information regarding payroll and assigned resources.

Conduct of Military Forces: Complaints, accusations, and sentences regarding human rights violations perpetrated by members of the armed forces and the level of public trust in the armed forces.

7

Protecting Human Rights

Investigation and Conviction of Human Rights Violations: Existence and functioning of specialized investigative units, number of complaints, prosecutions, and convictions, handling of emblematic cases, and degree of security forces’ collaboration with investigations.

Protection Mechanisms: Structure and functioning of domestic protection mechanisms and implementation of international protection measures for human rights defenders who have been victims of attacks or threats.

Hate Speech: Analysis of attacks and smear or defamation campaigns against human rights defenders.

8

Improving Transparency

Scope and Implementation of the ‘Law of Access to Public Information’: Type of information categorized as restricted or of limited access, period of classification, availability and quality of statistics related to security and justice, information requests granted and denied, and related fees.

Budget and Spending Transparency: Access to public information on budget allocations and spending on security, justice, and defense.

Disclosure of Public Officials’ Statement of Assets: Level of official compliance with disclosure norms, and the degree to which such statements are made available to the public.

METHODOLOGY

The Central America Monitor is based on the premise that accurate, objective, and complete data and information are necessary to reduce the high levels of violence and insecurity, and establish rule of law and governance in a democratic state. This will allow efforts to move beyond abstract discussions of reform to specific measures of change.

The Monitor is based on a series of more than 100 quantitative and qualitative indicators that allow a more profound level of analysis of the successes or setbacks made in eight key areas in each of the three countries. More than a comprehensive list, the indicators seek to identify a way to examine and assess the level of progress of the three countries in strengthening the rule of law and democratic institutions. The indicators seek to identify the main challenges in each of the selected areas and examine how institutions are (or are not) being strengthened over time. The Monitor uses information from different sources, including official documents and statistics, surveys, interviews, information from emblematic cases, and analysis of existing laws and regulations.

The indicators were developed over several months in a process that included an extensive review of international standards and consultation with experts. The eight areas analyzed by the Monitor include: