TABLE OF CONTENTS

Download the report in PDF format

Listen to a podcast that the authors posted from Honduras on May 1, 2023.

Overview:

- Four current and former WOLA staff members—Adam Isacson, Maureen Meyer, Ana Lucia Verduzco, and Joy Olson—visited Honduras from April 26th to May 5th, 2023.

- Why we visited: WOLA has done extensive research on the U.S.-Mexico border, throughout Mexico and the Mexico-Guatemala border, and the Darién Gap has begun to draw attention. But the U.S – Mexico border is the end of a long journey, and much of what happens elsewhere along the U.S.-bound migration route is poorly understood. WOLA wants to tell the story of what’s happening at key stages of the migration route because needs are urgent and the region is experiencing unprecedented human mobility.

- What we found: Honduras, like its neighbors, now experiences four kinds of migration:

- Hondurans who are departing

- Hondurans who are internally displaced

- Hondurans deported back from other countries

- International migrants transiting the country

- As everywhere along the migration route, numbers of international migrants passing through the country are up, as the land route from South America has opened up since 2021. Many U.S.-bound migrants are from other continents. To reflect this new reality, humanitarian aid providers call on international and national funding to be more consistent and reliable.

- For migrants transiting Honduras, the country is a “respiro”—a place to catch one’s breath—or even a “sandwich” between arduous and unwelcoming journeys before (Darién Gap, Nicaragua) and after (Guatemala, Mexico).

- This is largely because Honduras is neither deporting nor detaining most migrants, and it has waived a fine that it had been charging for travel documents required to board buses. That fine had left many migrants in Honduras stranded, while providing corrupt authorities with an opportunity for extortion. Upon entry, most migrants now register directly with the government without the need to pay a fee. This reduces opportunities for organized crime. It also makes transiting the country slightly more bearable and provides a more accurate registry of those who enter the country. This “amnesty” policy is a necessary alignment with reality. Honduras should make it permanent, and other countries along the route would do well to emulate aspects of it.

- Migrants—both those transiting Honduras and Honduran migrants departing the country—are traveling with widely varying levels of information about what lies ahead. While some were aware of the “CBP One” app and the significance of May 11, 2023, the day that Title 42 ended, almost no migrants with whom WOLA interacted had clear knowledge of the complex U.S. asylum process. Some did not even know how many more countries remained to cross in the days ahead.

- The United States and Mexico deport 1,500-2,000 Honduran migrants in a typical week. Attention to deported migrants as they arrive in Honduras is supported by the U.S. government, indirectly through international organizations and humanitarian groups. Conditions are relatively dignified and well resourced, despite some serious short-term needs. But assistance with reintegration largely stops at the doors of the reception centers. Security risks are high, but economic and psychosocial needs are the most urgent.

- Upon arrival in Honduras, deported migrants share alarming testimonies about the treatment they receive while in the custody of, and being transported by, U.S. law enforcement agencies. These rarely end up with investigations or discipline because pathways to reporting are often unclear or inaccessible, especially when witnesses are deported.

- International humanitarian officials and Honduran experts joined calls for more clarity and stability in U.S. immigration policy, and simpler access to reliable, current information about existing legal pathways to migration.

- Key reasons Hondurans migrate overlap in complex ways. It is hard to extricate economic need from the security situation as gang extortion has shuttered businesses and depressed economies. Corruption—and impunity for corruption— in turn feed a national malaise and sense of rootlessness or hopelessness that spurs migration. Add to these: discrimination, domestic violence, the effects of climate change, and the need to provide remittances to loved ones.

- WOLA’s time in Honduras was a reminder of the pressing need to find long-term alternatives to mass migration flows. These include community-based and institutional reforms that address the conditions forcing people to leave: poverty, violence, impunity, corruption, persecution, climate change, domestic violence, and a general sense of “rootlessness.”

- Experts and service providers warned against being tempted by quick fixes that promise short-term results at great long-term cost, like the state of emergency and mass incarceration that President Nayib Bukele is carrying out in neighboring El Salvador.

Full report

Introduction

Over 10 days in late April and early May 2023, a team of researchers from the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) visited Honduras to examine the challenges of migration at a historic moment of human mobility in the Americas. We wanted to understand international migration through Honduras, which grew quickly from a trickle to a torrent after migration through Panama’s treacherous Darién Gap region began on a large scale in 2021. WOLA and other groups have examined the migration phenomenon in the U.S.-Mexico and Mexico-Guatemala border regions, and other organizations have looked at the Darién Gap. The situation of migrants crossing Honduras, however, has received very little attention.

Border crossings and jurisdictions mentioned in this report. (WOLA staff visited all sites highlighted in color.)

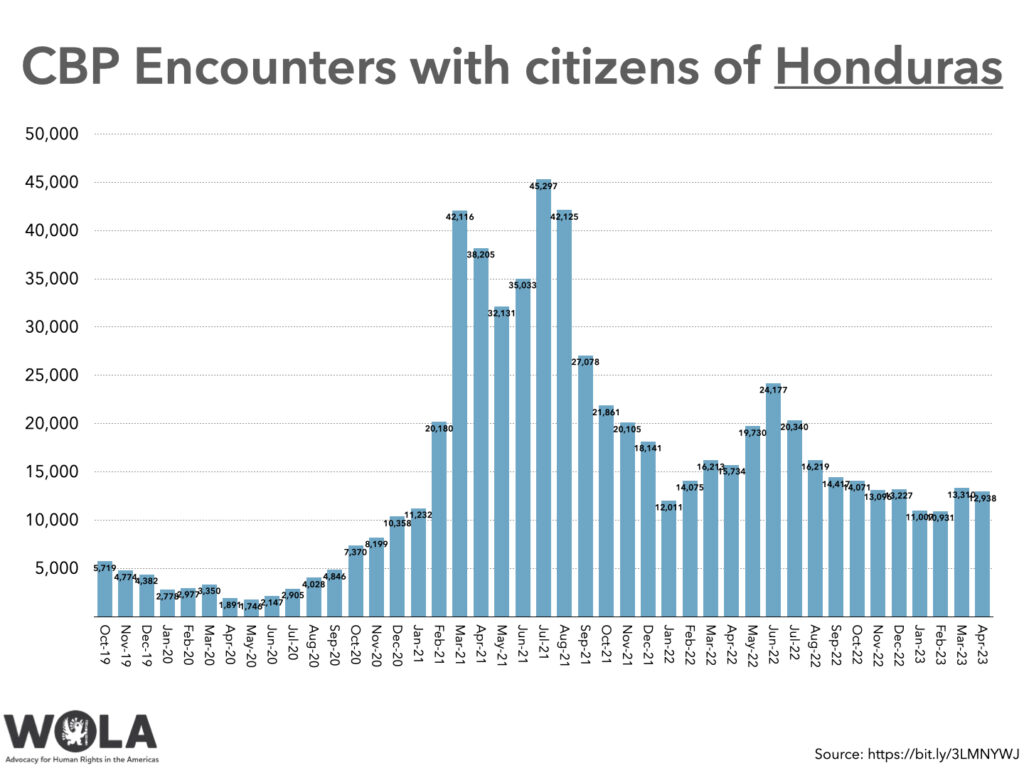

We also wanted to understand movements of citizens of Honduras, which is virtually tied with Guatemala as the second country of origin of migrants encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border so far during the 2020s. During this decade, U.S. border authorities have encountered Hondurans who have left their country 662,470 times. [1] During those same years, the United States, Mexico, and other countries have returned Hondurans to their country 236,176 times. [2] And an unknown number of Hondurans—at least 270,000—are displaced within the borders of their own country.

I. Migrants transiting Honduras

The increase in migration through Honduras has been striking. In 2019, Honduras counted 34,206 of what it calls “irregular” migrants, mostly from Cuba. In the pandemic year of 2020, that fell to 8,154 migrants, mostly from Haiti, and rose to 17,590 in 2021 (Haiti and Cuba).

Then, in 2022, migration expanded more than tenfold: Honduras counted 188,858 “irregular” migrants, mostly from Cuba and Venezuela. Of the 151,389 adult migrants last year, 34 percent were women. Through May 24, 2023, Honduras counted another 103,049 “irregular” migrants, mostly from Venezuela, Haiti, and Ecuador; of the 86,140 who were adults, 27 percent were women. [3]

These totals are less than, but similar in trends to, the number that Panama has been counting in the Darién Gap region straddling North and South America, where almost no migrants emerge from the jungle without being counted. [4] Honduras, by contrast, has several road crossings and other entry points, both official and unofficial, along its border with Nicaragua.

This figure does not include migrants from Nicaragua who are not considered “irregular” in Central America’s northern four countries, which do not require passports of each other’s citizens. The number of Nicaraguan migrants who passed through Honduras and did not return is hard to estimate. Honduran data, however, show that 155,522 more Nicaraguan citizens passed into Honduras than passed back into Nicaragua through the two main Honduras-Nicaragua border crossings in the 2022 calendar year. [5] That year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) counted 216,239 encounters with Nicaraguan migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. [6]

In January 2023, the U.S. and Mexican governments began expelling Nicaraguan migrants into Mexico, and Nicaraguan migration plummeted at the U.S.-Mexico border to 4,983 CBP “encounters” between January and April. Similarly, just 5,073 more Nicaraguan citizens passed into Honduras than passed back into Nicaragua through the two main Honduras-Nicaragua border crossings between January and April 2023.

While most 2023 migrants have come from Venezuela (35 percent), Haiti (15.4 percent), and Ecuador (14.8 percent), the variety of nationalities passing through Honduras is large—114 so far this year—and spans continents. In Danlí and Trojes, near the Nicaragua border, WOLA staff spoke to migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.

Honduras’s post-May 11 data show only a very modest decrease in migration after Title 42’s end, which contrasts with the sharp decreases in migration measured at the U.S.-Mexico border and in northern Mexico.

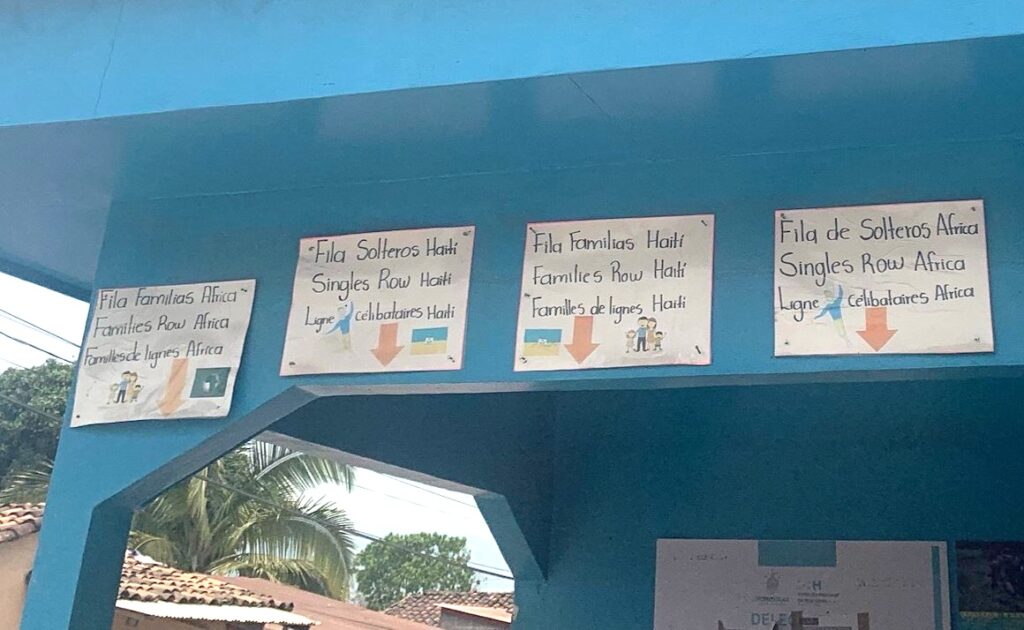

Signs outside the migration delegation. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Signs outside the migration delegation. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Migrants stay in tents outside the migration delegation, waiting to continue their journey north. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Migrants stay in tents outside the migration delegation, waiting to continue their journey north. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

A. Their journey

By the time they arrived in Honduras, migrants were exhausted and stressed. We saw many babies and young children. All were so exhausted that very few were crying.

Most had been through:

- Colombia and Venezuela, where they faced a high risk of being preyed upon by criminal groups.

- The Darién Gap, from where people with whom we spoke shared horror stories of arduous terrain, treacherous river crossings, seeing dead bodies, in one case even seeing people die from a steep fall.

- Panama and Costa Rica, where they were whisked through quickly and expensively if they had money, or stuck for days or weeks if they did not.

-

Many said that Nicaragua was worse than the Darién Gap.

Many said that Nicaragua was worse than the Darién Gap. This was because of mistreatment and theft not just from the Nicaraguan authorities, but from “all actors,” one international aid worker explained. [7] Some interviewees cited xenophobia and, in the case of Venezuelans, hostility toward people fleeing an allied regime. Nicaragua’s government barely coordinates with regional neighbors or international organizations on migration management. International human rights groups and journalists are currently unable to enter the country to document abuse.

- All along the route, migrants and aid workers cited harsher treatment of Haitian and other darker-skinned migrants.

- All migrants are preyed upon for money: at times through theft, more often through price-gouging, even for basic items like food, water, bathroom access, or mobile phone minutes. This vulnerability appears even greater for people from other continents.

The Las Manos border crossing into Nicaragua, where the flag of the ruling Sandinista Front is in view, but Nicaragua’s blue-and-white flag is not. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

The Las Manos border crossing into Nicaragua, where the flag of the ruling Sandinista Front is in view, but Nicaragua’s blue-and-white flag is not. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Using WhatsApp and other social media, migrants share information about the best crossing routes from Nicaragua. Currently, the most frequented route is informal border crossings at Trojes, near Danlí, El Paraíso, where WOLA visited.

WOLA heard wide variation in migrants’ knowledge about:

- What lay ahead for them on the migration route, in terms of risks and even geography. Some did not even know that Guatemala would be the next country through which they would pass.

- What pathways are available to enter and work legally within the United States, such as asylum requirements, use of the CBP One app, humanitarian parole, and other policies.

-

Some, though not all, believed that they needed to arrive in the United States before Title 42’s May 11, 2023 expiration date.

The significance of recent changes in U.S. policy, particularly the Biden administration’s replacement of Title 42 with a new “transit ban” asylum rule. Some, though not all, believed that they needed to arrive in the United States before Title 42’s May 11, 2023 expiration date.

Some migrants were aware of these developments. None had detailed knowledge. Most were reliant on rumor, spread largely via social media. Some had family or friends in the United States offering guidance in something close to real time via their mobile devices, an ability that was rare even 10 years ago.

Those who had heard about the Biden administration’s two-year humanitarian parole program for citizens of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela did not consider it to be an option. The barriers—the need to have a passport, the need to have a U.S.-based sponsor—were too high. A representative of an international organization in Tegucigalpa said that only 16 percent of those four countries’ citizens hold a valid passport, and the percentage is particularly minimal for Venezuelans. [8] And very few have sponsors inside the United States, even though, as CBS News revealed in May 2023, 1.5 million people in the United States—50 times the monthly maximum of 30,000 permitted migrants—have registered to be sponsors under the new program. [9]

B. Transiting Honduras: a respite for some

A frequent comment was that Honduras is one of the easier countries to pass through: a place for migrants to “catch their breath” along the route.

Though gangs and organized crime are a big part of daily life for Hondurans, at least three experts and service providers interviewed noted few reports of them preying on international migrants. [10] Ransom kidnappings of migrants are virtually unheard of, nor are cases of xenophobic attacks. Migrants take care not to stay for very long, though, if they can avoid it. Even shelters are below capacity as most migrants appear to want to ensure that they are not a “moving target.”

This may be wise. The International Organization for Migration counted 16 deaths of migrants on Honduran territory in 2022. The causes of death included violence, vehicle accidents, drowning, or illness exacerbated by lack of adequate health care. [11] WOLA heard reports of human trafficking and gang activity around El Paraíso’s Las Manos border crossing, and some cases of corrupt police shaking migrants down nationwide.

In fact, migrants’ negative encounters with police appear to be more frequent than their negative encounters with organized crime. Local media have reported cases of corrupt police demanding bribes from migrants in Choluteca, near Nicaragua, and Ocotepeque, near Guatemala. [12] In December 2022, Agence France Presse reported that police were using the pretext of “invalid” COVID vaccination cards to stop Nicaraguan migrants, letting them proceed only after paying $40 bribes. [13]

Beyond crime and violence, a big complaint was transportation companies and others, like food vendors, taking advantage of migrants by vastly overcharging them. The need to pay $50 per person bus fare, up from about $37, is onerous, especially for those traveling as families. [14] For Honduran transportation companies, it is a windfall: a bus company employee at the Danlí terminal told WOLA that they are running 25 buses per day, with 50 passengers each paying $50: a daily gross of $62,500.

In Trojes and Danlí, people obtain travel documents, eased by the fee amnesty, and board those $50 buses directly to the Guatemalan border in Agua Caliente, Ocotepeque, a 12 to 16-hour ride. Some buses change at a makeshift “migrant terminal” in Tatumbla, just beyond Tegucigalpa’s outskirts. [15] This arrangement keeps most migrants out of the capital.

Buses bound for the Guatemala border depart from the terminal in Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Maureen Meyer.

Taxis that transport migrants from an informal Nicaragua-Honduras border crossing to Trojes town center. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Taxis that transport migrants from an informal Nicaragua-Honduras border crossing to Trojes town center. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Most migrants don’t travel through Honduras with a coyote (smuggler). [16] It is unnecessary because of the relative ease of obtaining a travel document (though it may require hours of lining up in intense heat). As with other Central Americans, Nicaraguans may travel in Honduras without a passport.

Those who do travel with a coyote take informal crossings, often in very rural areas like Olancho. Cubans, who usually start their journeys in Nicaragua due to Managua dropping visa requirements, are believed to travel often this way. [17]

When international migrants reach the Guatemala border, usually at the crossing in Agua Caliente, Ocotepeque, the route becomes more difficult. There is little state or international humanitarian presence in that region. (WOLA did not visit Ocotepeque because it was a full day’s drive from everywhere else on our itinerary, and there are few service providers to speak with once one arrives.)

In Guatemala, the government of President Alejandro Giammattei has a much different approach to international migration than Honduras. Guatemala is “hyper-sensitive” to in-transit migrants, one diplomat put it; a Honduran journalist described its blocking of migrants as “violent.” [18] Giammattei at one point called himself “el matacaravanas” (“the caravan-killer”). [19]

The country’s border police (DIPAFRONT) frequently expels migrants from Agua Caliente back into Honduras. During 2022, Guatemalan authorities reported “rejecting” into Honduras “5,593 Venezuelans, 1,411 Cubans, 929 Haitians, and 215 Nicaraguans.” [20] After being expelled, migrants normally disperse and re-cross at irregular paths not far from formal border crossings. It is essential to do this with a coyote.

The expulsions are tied to corruption: police will abstain from expelling if a migrant can pay a bribe. “Venezuelan migrants say ‘Guatemala—uff.’ They extort the whole way,” an international aid worker said, referring to Guatemala’s national police. [21]

Because Guatemalan police expel anyone who doesn’t pay a bribe, it is usually necessary to hire a coyote to get through Guatemala. Coyotes actively seek customers on the Honduran side of the border. This lends a tense atmosphere to this part of Ocotepeque. [22]

More than one interviewee described Honduras as being caught in a “sandwich.” [23] Nicaragua’s regime appears to share little information or collaborate with its neighbors on migratory flows, while allowing migrants to be mistreated. [24] Guatemala aggressively expels non-Honduran migrants back into Honduras, while setting up incentives within its borders that benefit smuggling. This state of affairs is unsustainable. Honduras and its Central American neighbors need to coordinate their response far more closely.

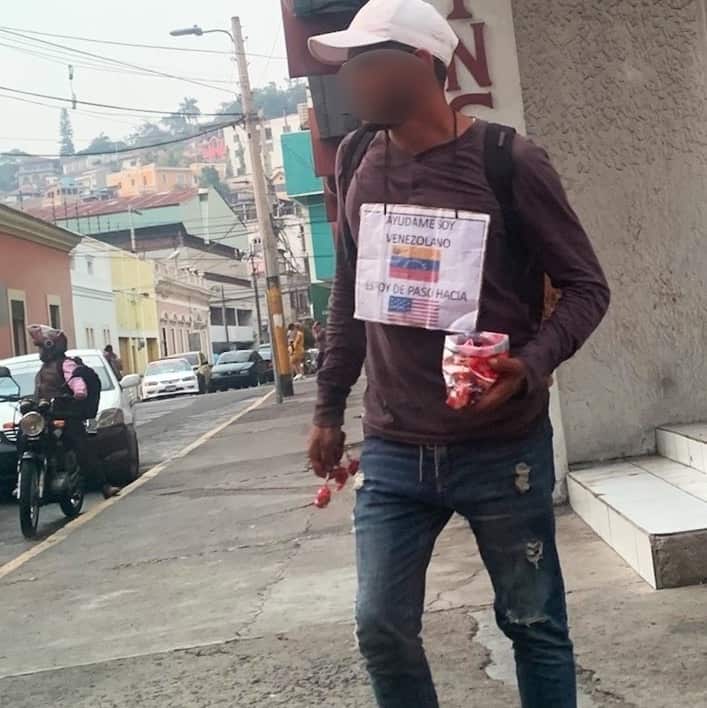

Venezuelan man in Tegucigalpa city center. His sign reads, “Help me, I’m Venezuelan, on my way to the United States.” April 27, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Venezuelan man in Tegucigalpa city center. His sign reads, “Help me, I’m Venezuelan, on my way to the United States.” April 27, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

C. The fee amnesty is a good policy

In May 2022, four months into the administration of President Xiomara Castro, the Honduran government made the consequential decision—implemented in August 2022—to waive a hefty fine, equivalent to about US$240, on migrants who crossed into Honduras “irregularly.” The country’s migration law (Ley de Extranjería) requires such migrants to pay a fine in order to receive a special permit, often called a “safe conduct” (salvoconducto), allowing them to be present in the country. [25]

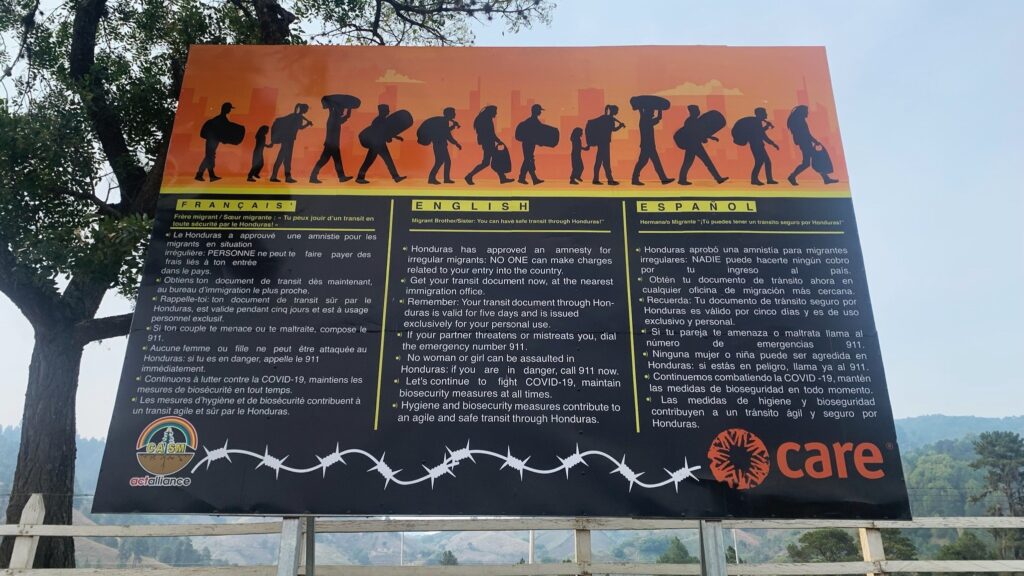

Informational billboard at Nicaragua-Honduras border crossing near Trojes. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

While Honduras’s migration authority (National Migration Institute, Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) rarely deports or detains migrants, it is impossible to board a bus to get across the national territory without this permit. With the amnesty in place, migrants may obtain, free of charge, a document with a QR code allowing them to remain in the country for five days. This requires waiting in a potentially long line and registering, which in turn requires entering biometric data in a database that is shared with U.S. Customs and Border Protection. [26]

The amnesty on migratory fines brought a jump in the number of people who register. One diplomat estimated that 70 percent of migrants are now likely to be registering with the Honduran government, up from 30 to 40 percent before August 2022. [27] Data from Honduras’s INM show that the number of “irregular” migrants recorded as transiting the country jumped 90 percent after the amnesty began, from July to August 2022 (11,976 to 22,717). [28]

This gives the U.S. and Honduran governments much greater visibility, including biometrics, about who is coming. It also eliminates, for most, the need to hire a coyote, dealing an important blow to organized crime. The amnesty “appears to have damped down the criminal element,” one U.S. official put it. [29]

Some non-governmental advocates warned, however, that 5 days is often not enough time to transit a country. A family with children, for instance, may take days to raise the $50 per person that bus companies charge.

The Honduran Congress must renew the amnesty periodically. It has done so twice, and the next expiration date was May 31. Another expiration date, for the end of 2023, was approved at the last minute on June 1. The repeated extensions are mildly controversial because the fine was a source of revenue, netting Honduras over $9 million during the first 6 months of 2022. [30]

The uncertainty about regular amnesty renewals underline the importance of Honduras acting this year to pass a long-awaited update to its 2004 migratory law (Ley de Extranjería), which could do away with the fine. Many whom we interviewed regarded movement on this law to be a key litmus test of the government’s political will.

The U.S. government may not be delighted that Honduras (and Panama, and Costa Rica) permits U.S.-bound migrants to cross its territory with relative ease. As one official put it, “The Honduran government says that ‘migration is a right.’ Our response is that ‘immigration [to the United States] is not a right.’” [31]

On the ground in Honduras, though, there is really no other option. The amnesty aligns policy with reality at a time of mass migration through a country lacking resources to manage it. It gives more visibility to the U.S. and Honduran governments about who is coming, and it starves organized crime of revenue. The amnesty is a smart policy under these circumstances.

“Migrant bus terminal” in Tatumbla, outside Tegucigalpa, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

D. Migrant Services

To provide basic assistance to international migrants in transit, the Honduran government—with major support from national and international humanitarian groups—maintains Centers for Attention to Irregular Migrants (CAMI) in Danlí, Choluteca, and Gracias a Dios near the Nicaragua border, as well as Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula. Plans are underway to open another in Ocotepeque near the Guatemalan border.

A key support for the CAMIs and other services in the El Paraíso area, where WOLA visited, is the Fundación Alivio del Sufrimiento, an organization founded by Father Ferdinando Castriotti, which participates in a consortium called LIFE Honduras, along with Action Against Hunger, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Pure Water for the World, the ChildFund, the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA). The consortium has established a new shelter in El Paraíso that it expects to hand over, eventually, to the Honduran government. [32]

The LIFE Honduras consortium also supplies the government’s CAMI in Danlí, a large facility. It operates a temporary rest center near the Nicaraguan border in Trojes, which opened in September 2022, designed to provide temporary shelter to families and disabled people. About 75 people can fit in its tents on a lot near the mayor’s office in the town’s center. [33]

When WOLA visited the CAMI in Danlí on the morning of Sunday, April 30, several hundred migrants from a wide variety of countries were waiting in a long line for their travel documents. There, and outside the INM facilities in Trojes on April 29, WOLA staff spoke to dozens of people waiting to obtain their travel permits.

Temporary Rest Center. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Temporary Rest Center. Trojes, Honduras. April 29, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

While most of those with whom we spoke were Venezuelan, others came from Haiti, Cuba, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. Some communicated through smartphone apps translating their words into and from Spanish. Most had passed through the Darién Gap several days earlier, and were exhausted from that journey and the subsequent passage through Nicaragua. One Venezuelan mother had given birth in Panama.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Joy Olson.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Joy Olson.

Though Honduras offered the possibility of remaining in the country for five days, nearly all migrants with whom we spoke were not interested in resting, for instance at the new shelter in El Paraíso. They wanted to get to the Danlí bus station and keep moving across the country.

Some were reluctant to stop and make themselves vulnerable, after encountering bandits, corrupt police, and price-gougers along the way. Others believed that they needed to arrive in the United States before May 11. Some, with almost no money, did not want to spend on food or lodging while still stationary.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Center for Irregular Migrants. Danlí, Honduras. April 30, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

II. Honduran migrants

Honduras is in a virtual tie with Guatemala as the 2nd nationality of migrants encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border since October 2019, when the U.S. government’s 2020 fiscal year began. Since January 2022, Honduras is fourth, behind Mexico, Cuba, and Guatemala. [34] Aggressive application of Title 42 expulsions into Mexico kept Honduran migration flat, though near historically high levels.

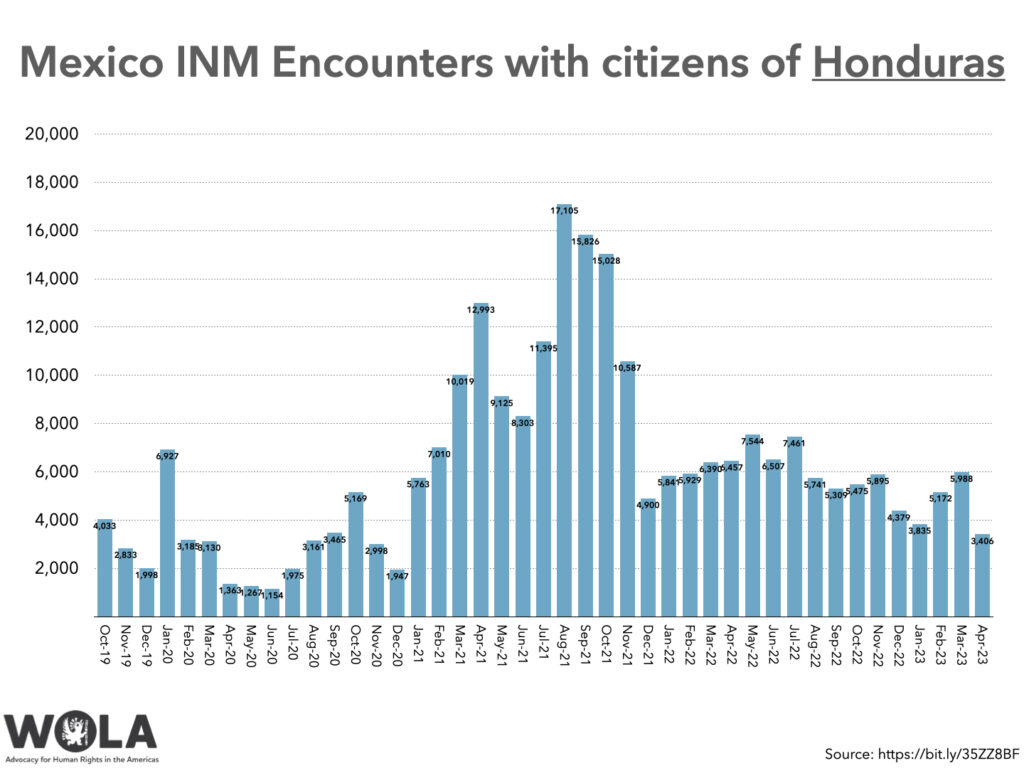

For its part, in 2022, Honduras ranked first for asylum claims in Mexico (31,074) and second only behind Haitians for the first 4 months of 2023 (10,993). [35] “Mexico is a second choice for asylum,” a Honduran journalist told WOLA. “There is work there; they speak Spanish. The cost of living is lower than in the United States. Working conditions are better than in Honduras for women. For those who may still wish to emigrate to the United States, asylum in Mexico buys time.” [36]

Mexico’s migration agents encountered 72,928 Hondurans in 2022, and deported 40,700. Of the adults deported, 13 percent were women. During the first four months of 2023, Mexican authorities encountered 18,401 irregular Honduran migrants, and returned 9,353. Of those returned, 12 percent were women. [37]

A “migration industry” profits from Hondurans seeking to leave their country. Coyotes embedded in communities are part of a larger network. Fees to take people to the United States now run $12,000-$15,000 per person. $20,000 pays for a “VIP” journey that, due to corruption along the route, allows a migrant to travel the entire time in a vehicle with no trouble at checkpoints. [38] Coyotes’ fees usually cover three attempts to migrate to the United States.

“Caravans” are no longer a mode of transportation. The hope of achieving “safety in numbers” and avoiding the cost of a coyote disappeared after caravans alerted the Trump administration and the region’s security forces, as well as cases of violent repression of migrants in caravans. [39]

A. Reasons for migrating

Some Honduran analysts and journalists expressed the sense that their fellow citizens are almost coming to view migration as a rite of passage. A journalist in San Pedro Sula told us of a middle-class colleague who chose to leave the country—not because of poverty or threats, but because, in his view, “I have a future, but this country does not.”

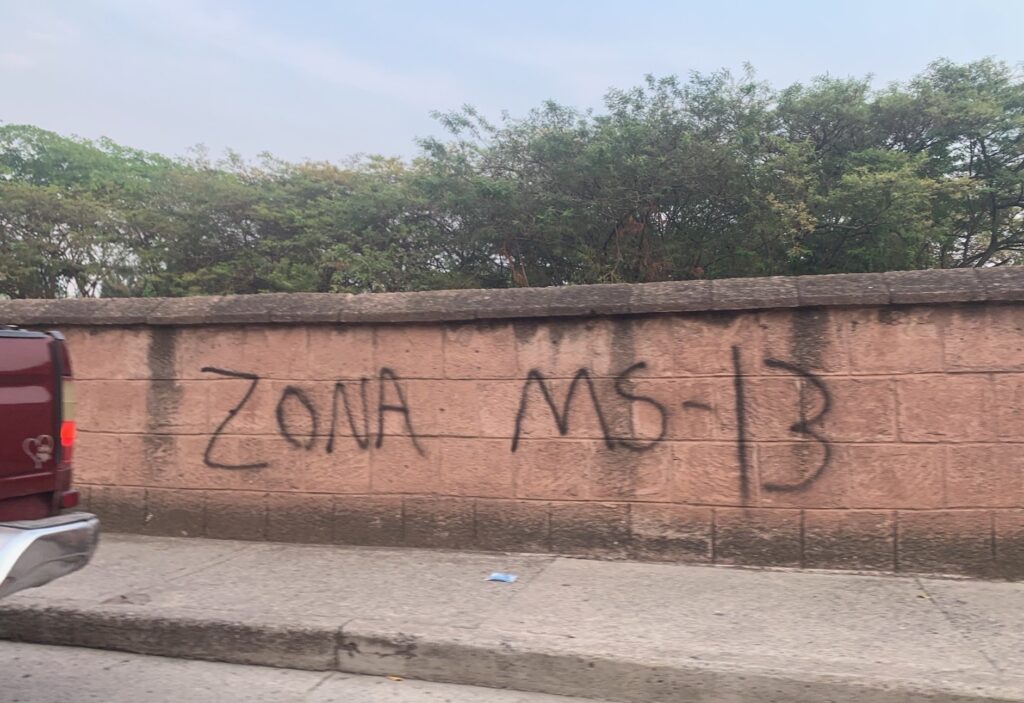

Graffiti tag reading “MS-13 Zone”, referring to the prominent Mara Salvatrucha gang. Tegucigalpa, Honduras. April 27, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Graffiti tag reading “MS-13 Zone”, referring to the prominent Mara Salvatrucha gang. Tegucigalpa, Honduras. April 27, 2023. Photo credit: Adam Isacson.

Other key reasons Hondurans migrate, usually to the United States, include:

- Economic need, including the need to send remittances back home. 48 percent of Honduran respondents to a 2021 NVSM survey, cited by USAID, said that their family experienced food insecurity within the past three months—more than double the result of a 2014 survey. [40]

- Economic need cannot be extricated from insecurity. Often, people have economic need because they’ve been extorted out of business.

- Violence and insecurity, like threats from gangs, threat of recruitment by gangs, and state forces’ failure to offer credible protection.

-

Corruption—and impunity for corruption—underlies insecurity, economic failure, and a sense of hopelessness and lack of rootedness.

Corruption—and impunity for corruption—which underlies insecurity, economic failure, and a sense of hopelessness and lack of rootedness.

- Domestic violence and a lack of resources for protections or aid in Honduras.

- Effects of climate change, especially hurricanes, severe storms, and droughts.

- Family reunification.

- The differential challenges that arise for women, Indigenous, Afro-descendant, LGBT, and disabled people.

- A lack of “rootedness” in the country. Some communities have lost a significant part of the population.

These reasons for leaving overlap. The 2021 NVSM survey found people citing multiple “push factors.” 94 percent mentioned economic reasons. 52 percent cited violence. 46 percent mentioned environmental causes, like droughts or storms. 46 percent cited political reasons, like persecution or corruption. 31 percent mentioned family reunification. [41]

These overlapping causes, especially violence and climate-influenced natural disasters, also cause Hondurans to displace internally. In early 2023, the UN Refugee Agency estimated that 271,799 internally displaced people (IDPs) were living in Honduras, plus 123,310 in an “IDP-like situation.” Combined, that is equivalent to nearly 4 percent of Honduras’s population. [42] Internal displacement is often a last resort before leaving the country entirely.

Honduras’s current government, inaugurated in January 2022, is struggling to meet high expectations for addressing these many causes of migration. It remains starved of resources—at least 30 percent of the national budget is service payments on debt equivalent to more than 60 percent of GDP—and beset by political and managerial challenges. [43] Remittance payments sent from Hondurans abroad now total at least 25 percent of GDP. [44]

Security experts whom WOLA interviewed observed that members of the National Police are too often linked to gangs. A Honduran migrant told ContraCorriente in 2023, “Look, the best thing we could do is not file a complaint. When this happens, the [criminal] organizations work with the police. Filing a report is like saying to the thug, ‘Look, it was so-and-so who reported you.’” [45]

If it has sufficient autonomy to carry out its work effectively, and the Honduran justice system maintains the basic conditions of independence and commitment, then establishing a Commission Against Impunity in Honduras (CICIH)—an anti-corruption body with prosecutorial powers—holds promise of attacking one of the root causes of Honduran migration: corruption. Also crucial to the justice system’s effectiveness against corruption is full transparency in the process of nominating the country’s next attorney general and deputy attorney-general on September 1, 2023. [46]

B. Deportations and returns from the United States and Mexico

Other countries returned 94,399 Honduran citizens to their home country in 2022—nearly 1 percent of Honduras’s population. Mexico returned 50 percent of that total, followed by the United States (46 percent) and Guatemala (3 percent). Of adult returnees, 23 percent were women. [47]

The pace of returns slowed somewhat between January 1 and May 24, 2023, as other countries sent back 23,505 Hondurans. 51 percent were returned from the United States, 45 percent from Mexico, and 3 percent from Guatemala. Of adult returnees, 20 percent were women.

The United States sent 358 migrant removal flights to Honduras in 2022, almost exactly one per day, according to a count kept by Witness at the Border. During the first four months of 2023, the pace slowed modestly, to 82 flights. [48] Mexico’s deportation buses declined to about 20 percent of their former total since the tragic fire that killed 40 people in a migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, on March 27, 2023. [49]

During the pandemic, Mexico began sending deportation buses without coordinating with Honduran authorities. This extended to ignoring repatriation agreements and standards. For a time in 2021 and 2022, Mexico would even leave busloads of Honduran citizens at the Guatemala-Honduras border, unattended, in the middle of the night—an echo of the way CBP practiced Title 42 expulsions at the U.S.-Mexico border. [50]

Upon return to Honduras, at least half of deported migrants seek to return north almost immediately. [51] Incentives to leave vastly outweigh incentives to stay. Some people have experienced losing everything multiple times, to natural disaster, economic ruin, or extortion.

The Honduran government, with help from international humanitarian organizations and charities, maintains three reception centers for deported migrants. One, near San Pedro Sula’s airport in La Lima, Cortés, receives deportation flights. One, in Omoa, on the Caribbean coast near the Guatemala border, receives buses, mainly from Mexico. A third, the Belén shelter in central San Pedro Sula, receives children and families who first arrive at the other two.

Attention to migrants at the moment of reception is dignified and reasonably well resourced, though facilities vary: in Omoa, there are no bathing facilities and people must “shower” in the ocean, while La Lima has nowhere for people to spend the night. Regardless, assistance with reintegration stops, in most cases, at the doors of the reception centers. Assistance programs for returned migrants do exist, and some are innovative, but their reach is limited to a small portion of those who need help.

Though security is a concern for migrants’ reintegration, most of deported Hondurans’ top-tier needs are economic and social. They include:

- Health needs.

- Psycho-social support, as many have been through trauma.

- Making it possible for children, especially adolescents, to stay in school.

- Focusing on the economic needs of women and girls, including women heads of household.

While protection screening in reception centers is welcome and important, it does not adequately capture returned migrants’ often urgent security needs. Upon return, migrants face the same security threats they were fleeing, like gangs, domestic violence, and generalized extortion. Unless they have a compelling threat to convey to a screening officer, and feel comfortable discussing it, they are on their own once they leave the reception center.

After they leave reception centers, deported migrants are vulnerable to violent crime and to the predations of corrupt officials. A 2019 “guide for people returning to Honduras,” published by the American Friends Service Committee, warns deportees to “avoid casual street encounters, including eye contact,” and to “be prepared for bribes, have $40-100 in cash in $10s & $20s in different pockets.” It adds, “The neighborhoods closest to the airport are controlled by MS-13 and the 18th Street gang. Take special caution in these areas.” [52]

Honduras’s resource-strapped government depends heavily on foreign donor and humanitarian-agency assistance to provide what services exist for returned Honduran migrants. Officials note that they already have difficulty meeting the needs of the existing, non-migrant population. Some international aid representatives voiced concern about the Castro government’s decision to close down municipal-level reintegration units for returned migrants, an initiative of the prior (Juan Orlando Hernández) government that had USAID and IOM support. [53]

Experts and service providers encouraged the Honduran government to invest more in attention to reintegrating deported people in regions beyond the country’s north coastal region. They called for:

- More investment in education at all levels, but especially for adolescents so that they may study instead of taking low-paying jobs.

- Full, long-term psychological attention for trauma victims.

- Efforts to help people feel rooted in Honduras.

- Assistance for returnees with disabilities.

- Specific basic goods and infrastructure for reception centers.

- Better transportation to migrants’ home communities, instead of just bus tickets to a few cities.

Migrant Reception Center in La Lima, Honduras. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Migrant Reception Center in La Lima, Honduras. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Beach-side migrant reception center, on property seized from organized crime in Omoa, Honduras. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Beach-side migrant reception center, on property seized from organized crime in Omoa, Honduras. Photo credit: Ana Lucia Verduzco.

Nearly all whom WOLA consulted noted that the Castro government is striking the right rhetorical notes and has adopted a more cooperative tone with agencies assisting migrants. “That’s half the battle,” one diplomat said. [54] However, it is under-resourced and still disorganized; a diplomat described the Honduran state’s approach as “fragmented,” with overlapping responsibilities between the Foreign Ministry, INM, and other agencies. [55]

Some analysts and aid workers mentioned that international transit migration is more publicized than Honduran migration, and that the government is giving Honduran migrants’ situation insufficient visibility.

Some specific suggestions for the Honduran government’s approach that we heard included:

- Establishing a point of contact within the government for returned migrants as they go through the reintegration process.

- Offering more than one night in shelter for both returned migrants and migrants in transit, especially families.

- Filling an existing gap in shelter space for women.

- Creating more room for NGOs to work.

- Being clearer about different agencies’ roles and structures.

- Investing in reception and migratory management infrastructure: INM installations are often underfunded and understaffed.

- Politically, being vocal about the presence and needs of Venezuelan refugees, despite the Castro government’s more accommodating stance toward the Maduro regime.

C. Abuse in U.S. and Mexican custody

Upon arrival in Honduras, deported migrants share alarming testimonies about the treatment they receive while in the custody of, and being transported by, U.S. federal law enforcement agencies. Frequent allegations include:

- Abusive and racist language, often unprovoked, with lots of yelling, including at children.

- Shackling at the hands and feet. Adults, including women, shackled in front of children.

- Inability to sleep while in custody. Lights kept always on, temperature kept very low, constant noise.

- Inability to use bathrooms during the entire duration of transport.

- Food that is rotten or still frozen, with some agents or guards deliberately throwing it on the floor for people to retrieve.

- Allegations of people being punched, shoved, and kicked.

- Denial of medical care, even for some serious illnesses. We heard of a recent case of a man returned with meningitis, needing other migrants’ assistance to walk from the plane.

- Non-return of shoelaces and belts.

- Non-return of some identity documents and other valuables.

These rarely end up with investigations or discipline because pathways to reporting are often unclear or inaccessible, especially when witnesses are deported. On May 4, 2023, the same day that WOLA staff interviewed migrants moments after their deportation plane landed in San Pedro Sula, the government of Colombia suspended U.S. deportation flights, citing a similar list of abuses perpetrated against its citizens. [56]

Migrants also describe human rights violations aboard Mexico’s deportation buses, on journeys that can take as much as four days if leaving Mexico’s northern border. These include denial of medical care, inability to move on long bus rides, and withholding food as punishment.

III. Assistance and policies

A. The government of Honduras

Many whom WOLA interviewed viewed Honduras’s December 2022 passage of an Internally Displaced Persons Law to be an important breakthrough. Now, though, the law needs regulation decrees to implement it, and will need resources.

When Honduras passed its basic migration law (Ley de Migración y Extranjería) in 2004, the idea of the country serving as a place of transit for hundreds of thousands of migrants per year was inconceivable. Now, the Darién Gap’s post-2020 opening to migration promises to make such migration flows a “new normal.” Honduras needs to move forward with plans to reform its migration law to adjust to this new reality, in particular by doing away permanently with steep fines charged to people who cross the border irregularly and do not intend to remain in the country.

B. The U.S. government

After migration from Central America increased sharply in 2013 and 2014, the Obama and Trump administrations increased assistance to Mexico and Central America’s northern countries. (The Trump administration cut economic and civilian institution-building assistance, but maintained assistance to security forces, particularly units with migration control duties. [57]) Some of that assistance went to security forces aiming to block or control the flow of migrants.

In Honduras, recipients of that equipment, training, advice, and intelligence included joint units including military personnel, like the “National Inter-Institutional Security Force” (FUSINA). [58] In 2014, a short-lived police operation, “Rescue Angels,” sought to take unaccompanied children off of buses at the Guatemala border, and demanded parents’ proof of custody. [59] People simply migrated via nearby informal crossings instead.

Today, the United States continues to assist Honduras’s Border Police, a unit of the National Police with about 600 members, perhaps 450 of them readily deployable. U.S. diplomats spoke highly of this unit’s current director. [60] Mainly with support from the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, Border Patrol agents—especially members of BORTAC, the agency’s SWAT team-like elite unit—train members of the Border Police. WOLA recommends strong vigilance over those programs given Border Patrol’s well-documented record of violating migrants’ rights with impunity at home. [61]

The Honduran military is not currently receiving assistance for migration control missions, though U.S.-assisted military units do carry out drug interdiction missions in border zones.

International humanitarian agencies report that they get as much as 90 percent of their budgets from U.S. sources, mainly the State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM). PRM supports transit and processing of people in Honduras who qualify for refugee status. (There are just 20,000 spaces for refugees this year from all of Latin America. [62])

USAID supports reception and reintegration efforts for returned migrants, including small-business training for “several thousand” returnees in the past year. [63] One non-governmental advocate described these trainings as “how to do a job interview, things like that.” [64] USAID does not support any migration enforcement efforts.

Service providers and experts in Honduras offered generally constructive critiques of U.S. programming for migrant communities in the country.

- Some expressed the common view that a majority of funding remains in the United States, and in the administrative expenses, representational expenses, and salaries of USAID’s non-profit and for-profit contractors. A service provider called on USAID to offer more contracts to local operators. [65] Even if they don’t have the same capacity to carry out all of the agency’s stringent documentation and reporting requirements, local organizations are closer to the community and their operating expenses are significantly smaller.

- That service provider described as a “utopia” some of USAID’s efforts to create private-sector employment for deported migrants. Job opportunities are scarce. Even if a small business is successful, it is vulnerable to extortion. Pay scales are very low: call centers, for instance, pay as little as $350 per month. [66] Space in trainings is very limited compared to the demand, with barely over 10 percent of applicants able to participate.

-

Some experts and service providers recommended emulating locally run, community-based projects that have successfully de-incentivized adolescent children from both gang membership and migration.

Some experts and service providers recommended emulating locally run, community-based projects that have successfully de-incentivized adolescent children from both gang membership and migration by teaching them trades, offering psycho-social support, and including a strong community organizing component. An example well known to WOLA is OYE, an initiative in El Progreso that provides skills, entrepreneurship, and leadership training alongside health support, while awarding high school and university scholarships to over 430 young people, whose co-founder now sits on our organization’s board, [67]

- Many whom WOLA interviewed recalled that the only way to “stabilize” migration—in Honduras and all along the route—is to use approaches like this to address the many conditions, discussed above, forcing people to leave: poverty, violence, impunity for the corruption and human rights abuse that worsen both, climate change, domestic violence, and the general sense of “rootlessness.”

- Violence and extortion, in particular, are exacerbated by the gang phenomenon and governments’ inability or unwillingness to protect victims. However, experts and service providers warned against “quick fixes” that promise short term results at great long-term cost. Key examples of these include the state of exception and mass incarceration that President Nayib Bukele is carrying out in neighboring El Salvador, and the state of exception that the Honduran government declared in December 2022 for over 160 neighborhoods in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, extended for another 45 days on May 20. [68]

International humanitarian officials and Honduran experts joined calls for more clarity and stability in U.S. immigration policy. While the U.S. stance on pathways like asylum remains complex and ever-changing, it is incumbent on the U.S. government to do more to inform about these pathways and their complexities. Proposed regional processing centers, including one slated for Guatemala, could help fill this need, if they are accessible despite likely high demand, and do more than just issue denials. [69]

Some called on the U.S. government to continue expanding temporary work visa programs, particularly the H-2B non-agricultural program, but only if these come with stronger protections to guarantee decent working conditions and wages, and do not make one’s migratory status dependent on a single employer. One analyst noted that Spain already has a temporary work visa program open to Hondurans, and that nearly all participants return to Honduras when their time is up. [70]

C. The international community

International funding for attention to migrants—those transiting Honduras as well as those displaced or deported—is precarious and insufficient as demand increases. A UN agency official said pointblank, “There are not enough resources here.” [71]

Staff at the respite facility in Trojes, for instance, told us that they only had funding to provide about 300 meals per day, when the population passing through the town averaged 800 migrants per day. “All basic needs are falling short,” a coordinator told us, including to help pay transportation costs of adult and family migrants stranded there for lack of bus fare. Worse, the facility only had funding secured through the month of May. [72]

Short-term funding may make sense when shifts in migration are rapid and unpredictable. Investing heavily in one border crossing sector could be a poor use of scarce resources if migration suddenly shifts to another area. But the problem is that the resources are scarce to begin with. And it is difficult to contract personnel or ensure adequate supplies when funding is always in danger of running out.

“If resources for humanitarian aid suddenly restrict, like if the United States changes its policy,” the UN official warned, “there could be a major crisis here.”

Conclusion and final recommendations

WOLA is grateful to its supporters for making it possible for staff to observe and report on the challenges of migration from, to, and through Honduras. We learned more than we expected to, and we’re grateful to the experts, officials, humanitarian workers, and civil society partners who shared their time and knowledge with us.

As long as migration’s “root causes” and “push factors” remain strong, we encourage the international community to continue supporting efforts to keep transit migration through Honduras orderly and safe, to increase efforts to reintegrate Honduran migrants who have been returned, and to provide protection and opportunity for Hondurans who are internally displaced, or at risk of displacement.

We encourage the Honduran government to continue the amnesty on fines that has made international transit migration safer and more orderly while dealing a blow to organized crime and extortion. We urge the Castro government to protect its citizens from gang violence and extortion without resorting to painful El Salvador-style crackdowns, which in turn means ending impunity for corruption, which has spurred much migration by benefiting gangs and organized crime.

We encourage the U.S. government to continue its support for humanitarian efforts that ease conditions and guarantee protection for all four categories of people undergoing forced mobility in Honduras: international migrants in transit, returned Hondurans, displaced Hondurans, and Hondurans about to migrate. We urge the Department of Homeland Security to vastly step up its actions to hold accountable personnel who abuse and mistreat migrants in custody.

WOLA remains closely engaged with the situation of migrants along the U.S.-bound route and throughout the region, and will continue posting reports, commentaries, podcasts, infographics, and other updates and recommendations. We will continue to make all of these resources available, free of charge and usually in both English and Spanish, on our website (www.wola.org).

WOLA thanks our former executive director, Joy Olson, for accompanying us on this research visit and reviewing this report.

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE REPORT.

Endnotes

[1] “Nationwide Encounters,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters.

[2] “Estadísticas,” Instituto Nacional de Migracion, 2023, https://inm.gob.hn/estadisticas.html.

[3] “Estadísticas.”

[4] “Estadísticas,” Migración Panamá, 2023, https://www.migracion.gob.pa/inicio/estadisticas.

[5] “Estadísticas.”

[6] “Nationwide Encounters.”

[7] International aid agency staff, Interview with international aid agency staff, Tegucigalpa, April 26, 2023.

[8] Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa, April 27, 2023.

[9] Camilo Montoya-Galvez, “1.5 Million Apply for U.S. Migrant Sponsorship Program with 30,000 Monthly Cap,” May 22, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-migrant-sponsorship-program-cuba-haiti-nicaragua-venezuela-applications/.

[10] International aid agency staff, Interview with international aid agency staff, Tegucigalpa; Staff, Fundación Alivio del Sufrimiento, Interview with staff, Fundación Alivio del Sufrimiento, El Paraíso, April 29, 2023; Journalist, San Pedro Sula, Interview with journalist, San Pedro Sula, May 2, 2023.

[11] “Missing Migrants Project,” International Organization for Migration, 2023, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/.

[12] Eva Galeas, “Policía de Honduras se convierte en el verdugo de los migrantes en tránsito,” Criterio, October 11, 2022, https://criterio.hn/policia-de-honduras-se-convierte-en-el-verdugo-de-los-migrantes-en-transito/.

[13] Agence France Presse, “Calvario de migrantes nicaragüenses arranca en Honduras,” Nicaragua Investiga, December 27, 2022, https://nicaraguainvestiga.com/nacion/102725-calvario-de-migrantes-nicaraguenses-arranca-en-control-fronterizo-de-honduras/.

[14] Allan Bu, “Honduras: sala de espera en un país de huida”, Redacción Regional, April 11, 2023, https://www.redaccionregional.com/tirano-tours/honduras/.

[15] Eva Galeas, “Violaciones a migrantes en tránsito se agudizan cada vez más en Honduras,” Criterio, December 2, 2022, https://criterio.hn/violaciones-a-migrantes-en-transito-se-agudizan-cada-vez-mas-en-honduras/.

[16] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa, April 26, 2023.

[17] Non-profit development agency staff, Interview with non-profit development agency staff, San Pedro Sula, May 2, 2023.

[18] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa; Journalist, San Pedro Sula, Interview with journalist, San Pedro Sula.

[19] Viviana Mutz, “Giammattei: ‘Tengo la fama de que soy el “matacaravanas” (de migrantes),’” República, February 17, 2023, https://republica.gt/guatemala/giammattei-tengo-la-fama-de-que-soy-el-matacaravanas-de-migrantes–202321720250.

[20] “Tras nueva política anunciada por Estados Unidos, se convocó a reunión extraordinaria extraordinaria CAP,” Instituto Guatemalteco de Migración, January 12, 2023, https://igm.gob.gt/tras-nueva-politica-anunciada-por-estados-unidos-se-convoco-a-reunion-extraordinaria-extraordinaria-cap/.

[21] International aid agency staff, Interview with international aid agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[22] Journalist, San Pedro Sula, Interview with journalist, San Pedro Sula.

[23] International aid agency staff, Interview with international aid agency staff, Tegucigalpa; Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[24] Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[25] Government of Honduras, “DECRETO No. 79-2022” (La Gaceta, August 4, 2022), https://criterio.hn/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Paginas-desde-GACETA-Aministia-No.-35993-4-DE-AGOSTO-DE-2022-SECCION-A.pdf.

[26] Honduran government official, Interview with Honduran government official with migration responsibilities, Washington, In Person, April 18, 2023; Staff of UN agency, Interview with staff of UN agency, Tegucigalpa, April 28, 2023.

[27] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[28] “Estadísticas.”

[29] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[30] Viena Hernández, “Migrantes de paso por Honduras se convirtieron en la caja chica del gobierno,” Criterio, August 10, 2022, https://criterio.hn/migrantes-de-paso-por-honduras-se-convirtieron-en-la-caja-chica-del-gobierno/.

[31] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[32] Staff, Fundación Alivio del Sufrimiento, Interview with staff, Fundación Alivio del Sufrimiento, El Paraíso.

[33] Interview with personnel at Temporary Rest Center, Trojes, El Paraíso, Honduras, April 29, 2023.

[34] “Nationwide Encounters.”

[35] “La COMAR en números” (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, May 2, 2023), https://www.gob.mx/comar/articulos/la-comar-en-numeros-332964?idiom=es.

[36] Journalist, Interview with journalist, Tegucigalpa, April 27, 2023.

[37] Unidad de Política Migratoria, “Boletines Estadísticos,” Secretaría de Gobierno de México, 2023, http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/Boletines_Estadisticos.

[38] Associated Press, “Guatemala usa la fuerza para frenar a caravana de migrantes; 5 impactantes videos,” Los Angeles Times en Español, January 18, 2021, sec. Internacional, https://www.latimes.com/espanol/internacional/articulo/2021-01-17/guatemala-usa-la-fuerza-para-frenar-a-caravana-de-migrantes-5-impactantes-videos; Non-governmental human rights NGO director, Interview with non-governmental human rights NGO director, Tegucigalpa, April 27, 2023; Non-profit development agency staff, Interview with non-profit development agency staff, San Pedro Sula.

[39] Associated Press, “Guatemala usa la fuerza para frenar a caravana de migrantes; 5 impactantes videos.”

[40] “Honduras: Climate Change, Food Security, and Migration” (U.S. Agency for International Development, 2022), https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00XXBJ.pdf.

[41] “Honduras: Climate Change, Food Security, and Migration.”

[42] “Honduras – Country Office Fact Sheet – February 2023” (UN Refugee Agency, February 28, 2023), https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/99198.

[43] EFE, “Elevated Public Debt a Major Challenge Facing Incoming Honduran Gov’t,” La Prensa Latina, December 6, 2021, https://www.laprensalatina.com/elevated-public-debt-a-major-challenge-facing-incoming-honduran-govt/.

[44] “Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP) – Honduras,” World Bank Open Data, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org.

[45] Allan Bu, “Desplazados por la violencia, invisibles para el Estado,” Contra Corriente, February 28, 2023, https://contracorriente.red/2023/02/28/desplazados-por-la-violencia-invisibles-para-el-estado/.

[46] WOLA, LAWG, DPLF, RFKHR, CEJIL, and HRW, “Nominating Board in Honduras Must Guarantee Independence and Transparency in Election of Attorney General,” Washington Office on Latin America, June 1, 2023, https://www.wola.org/2023/06/nominating-board-honduras-must-guarantee-independence-transparency-election-attorney-general/.

[47] “Estadísticas.”

[48] Tom Cartwright, “ICE Air Flights April 2023 and Last 12 Months” (United States: Witness at the Border, May 8, 2023), https://witnessattheborder.org/posts/5823.

[49] “Estadísticas,” 2023.

[50] Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[51] Personnel, Center for Returned Migrants, Omoa, Interview with personnel, Center for Returned Migrants, Omoa, May 4, 2023; Staff of Center for Returned Migrants La Lima, Interview with staff of Center for Returned Migrants La Lima, San Pedro Sula, Honduras, May 3, 2023; Staff of non-profit research organization, Interview with staff of non-profit research organization, Tegucigalpa, April 28, 2023.

[52] “A Guide for People Returning to Honduras” (American Friends Service Committee, September 2019), https://afsc.org/sites/default/files/documents/Honduras_English.pdf.

[53] Staff of UN agency, Interview with staff of UN agency, Tegucigalpa; Staff of non-profit research organization, Interview with staff of non-profit research organization, Tegucigalpa; Journalist, Interview with journalist, Tegucigalpa.

[54] Journalist, Interview with journalist, Tegucigalpa; Staff of UN agency, Interview with staff of UN agency, Tegucigalpa; Non-governmental human rights NGO director, Interview with non-governmental human rights NGO director, Tegucigalpa; Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[55] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[56] “Cancelación de vuelos y tratos degradantes motivan la suspensión temporal de llegada de retornados: Migración Colombia,” Migración Colombia, May 4, 2023, https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/noticias/cancelacion-de-vuelos-y-tratos-degradantes-motivan-la-suspension-temporal-de-llegada-de-retornados-migracion-colombia.

[57] “Northern Triangle of Central America: The 2019 Suspension and Reprogramming of U.S. Funding Adversely Affected Assistance Projects” (Washington: U. S. Government Accountability Office, October 15, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-104366.

[58] R. Evan Ellis, “Honduras: A Pariah State, or Innovative Solutions to Organized Crime Deserving U.S. Support” (Carlisle PA: U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, June 1, 2016), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1013816; “FUSINA: Resguardo de 47 puntos ciegos deja 90 migrantes irregulares requeridos en fronteras,” SEDENA Honduras, August 21, 2018, https://sedena.gob.hn/fusina-resguardo-de-47-puntos-ciegos-deja-90-migrantes-irregulares-requeridos-en-fronteras/.

[59] Cindy Carcamo, “Elite Honduran Unit Works to Stop Flow of Child Emigrants to U.S.,” Los Angeles Times, July 9, 2014, https://www.latimes.com/world/mexico-americas/la-fg-ff-honduras-border-20140709-story.html.

[60] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[61] See, for instance, hundreds of recent entries of alleged abuse at WOLA’s Border Oversight database: https://borderoversight.org/database/

[62] “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Border Enforcement Actions,” The White House, January 5, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/01/05/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-border-enforcement-actions/.

[63] Personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Interview with personnel, Embassy of the United States in Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

[64] Non-profit development agency staff, Interview with non-profit development agency staff, San Pedro Sula.

[65] Non-profit development agency staff.

[66] Staff of non-profit development organization, Interview with staff of non-profit development organization, Tegucigalpa, May 1, 2023.

[67] “About Us,” OYE: Organization for Youth Empowerment, 2023, https://oyehonduras.org/en/about-us/.

[68] Hector Silva Avalos, “States of Exception: The New Security Model in Central America?,” WOLA, February 22, 2023, https://www.wola.org/analysis/states-of-exception-new-security-model-central-america/; “Estado de excepción en Honduras se prolonga por 45 días,” Secretaría de Seguridad Nacional – Honduras, May 20, 2023, https://www.policianacional.gob.hn/noticias/policianacional.gob.hn/inicio.

[69] Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[70] Staff of non-profit research organization, Interview with staff of non-profit research organization, Tegucigalpa.

[71] Staff of UN agency, Interview with UN agency staff, Tegucigalpa.

[72] Interview with personnel at Temporary Rest Center, Trojes, El Paraíso, Honduras.