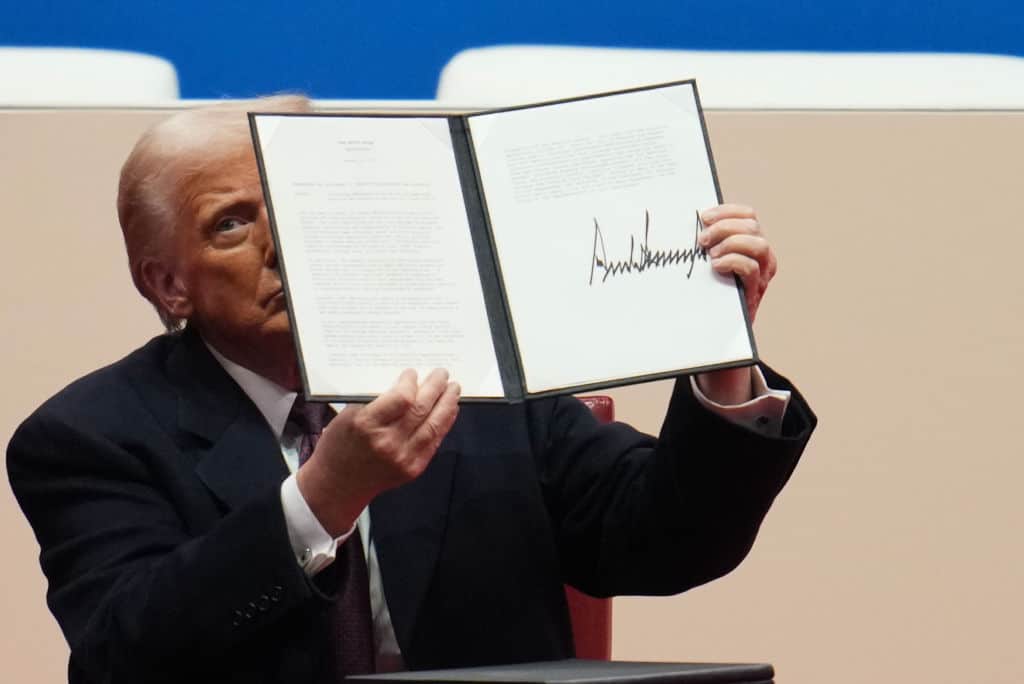

In his first 24 hours in office, President Donald Trump unleashed a series of executive orders. These 22 orders, crafted under the banner of his “America First” agenda, seek to reshape everything from immigration policy to foreign aid. At WOLA, we are closely monitoring these developments and have broken down what they mean for the people of Latin America and for U.S.-Latin America relations moving forward.

Below we explore key executive orders already enacted by the new administration and their far-reaching implications. From the shuttering of asylum pathways at the U.S.-Mexico border to a 90-day suspension of critical foreign aid programs, they mark dramatic shifts in U.S. policy that will reverberate across the region.

Ending asylum and other legal pathways

Section 208 of the Immigration and Nationality Act states clearly that anyone physically present in the United States has the right to apply for asylum if they fear for their life or freedom due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This right, added to U.S. law in 1980, applies regardless of how the non-citizen entered the United States.

Despite this, as of January 20 there is virtually no way to access the U.S. asylum system at the U.S.-Mexico border.

- One executive order has suspended the entry of undocumented migrants to the United States under any circumstances, citing an “invasion.” Border Patrol agents are now summarily turning people away. The order claims that those who make it to U.S. soil “are restricted from invoking” provisions like asylum. It further restricts undocumented people who cannot prove satisfactory medical and criminal histories.

- Another executive order canceled use of the CBP One smartphone app that, over two years, allowed more than 936,500 asylum seekers in Mexican territory to schedule appointments at U.S. border ports of entry. In June 2024, the Biden administration largely banned asylum access to people who crossed between the ports of entry, a rule that remains in place and continues to face legal challenges. Between the Biden rule and the CBP One shutdown, no practical pathway to protection currently exists at the border.

- The same executive order restarts the “Remain in Mexico” program, which requires non-Mexican asylum seekers to await their U.S. hearing dates inside Mexican territory. In January 21 comments, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum did not say that her government would oppose the restart of the program, which they state is a unilateral U.S. action. During the first Trump administration, more than 71,000 asylum seekers had to “remain in Mexico.” Human rights monitors compiled over 1,500 examples of violent crimes these people suffered during their wait at the hands of Mexican organized crime and corrupt officials. The program enriched cartels by providing them with a vulnerable population to kidnap and extort, and it complicated U.S.-Mexico relations. Still, with asylum out of reach and the border putatively sealed to undocumented people, it is not clear how the new administration plans to apply a revived “Remain in Mexico.”

- That order also requires U.S. diplomats to negotiate new “safe third country” agreements. These would obligate other governments to accept U.S. removals of third countries’ citizens, who would then have to seek asylum in the receiving country’s system. After much transactional cajoling, the first Trump administration signed so-called “Asylum Cooperative Agreements” with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The agreement with Guatemala was the only one to become operational before the COVID pandemic suspended them. According to a 2021 U.S. Senate report, it flew 945 non-Guatemalan asylum seekers to Guatemala City, zero of whom received asylum.

- The same executive order shuts down another pathway: using a presidential humanitarian parole authority to allow up to a combined 30,000 citizens of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, with passports and U.S.-based sponsors, to enter the United States without having to cross a land border. The program provided a two-year parole status inside the United States to over 531,690 citizens of those countries since late 2022, relieving pressure at the border.

- Another executive order, already facing multiple challenges in federal courts, and which has already been temporarily blocked by a federal judge, would undo the centuries-old conferral of U.S. citizenship on all people born in the United States, regardless of their parents’ status. The figure of birthright citizenship has been enshrined in the first sentence of the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment, with specific language, since 1868. It cannot be undone with a few paragraphs in an executive order.

A crackdown on asylum seekers and the closure of legal pathways is sure to reduce the number of migrants coming to the U.S.-Mexico border in the short term. Similarly, the first months of the last Trump administration saw the fewest Border Patrol apprehensions of migrants during the 21st century: fewer, even, than during the first months of the COVID pandemic.

With all pathways shut off, though, we can expect to see a steady increase in the number of migrants crossing into the United States without turning themselves in to Border Patrol: they will seek to avoid capture instead, even if they might have qualified for asylum. This is very dangerous: a larger number of people, including children and families, swimming the Rio Grande, climbing the border wall, or walking through the desert will mean a larger number of people perishing in the attempt. Border Patrol agents have found the remains of over 10,000 migrants on U.S. soil since 2000. The closure of safe pathways to protection will undoubtedly cause an increase in deaths as a share of the overall population of border crossers.

The “invasion” justification and dangerous domestic use of the U.S. military

Banning access to protection at the U.S.-Mexico border is plainly, nakedly illegal. To justify doing so, executive orders adopt a wild legal theory that asylum seekers and economic migrants meet the definition of an “invasion” under Article IV of the Constitution. Measures like the ban on all entries of undocumented people rest on the existence of an “invasion” and won’t get lifted until President Trump decides that the “invasion” has concluded.

This ludicrous idea that unarmed, non-state, leaderless individuals with humanitarian needs constitute an “invasion” first emerged in Republican circles during the Biden administration. When state governments—especially that of Texas—have sought to use the Constitution’s “invasion” clause to justify hardline anti-immigration policies, “courts have uniformly rejected” them, George Mason University Law School’s Ilya Somin explained in March 2024. That and other analyses point to an even graver danger of claiming that an invasion exists: the Trump administration might use it as a pretext to suspend U.S. citizens’ right to Habeas Corpus under the Constitution’s Suspension Clause.

One executive order would involve the armed forces directly. It charges the U.S. Northern Command, the body responsible for military activities in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and the Bahamas, with “the mission to seal the borders and maintain the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security of the United States by repelling forms of invasion including unlawful mass migration, narcotics trafficking, human smuggling and trafficking, and other criminal activities.” On January 22 the Defense Department announced the rapid deployment of 1,500 active-duty soldiers and marines to the border, adding, “This is just the beginning.”

Federal National Guard and small active-duty military deployments have operated at the border since the George W. Bush administration. Those have been explicitly “in support of” civilian law enforcement agencies at the border, with little likelihood of confrontation, or usually even contact, between combat-trained soldiers and migrants—or other civilians—on U.S. soil. Past border missions have been legal exceptions to the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act, which bans the use of soldiers in law enforcement—a phenomenon that WOLA has noted with concern in Latin America’s precarious democracies. Still, past administrations have sought to minimize these exceptions’ footprint and scope.

The mission foreseen in the new executive order is different. It will likely encourage Northern Command to emulate the model that the state of Texas has adopted for National Guard personnel at the command of Gov. Greg Abbott (R). At the borderline since 2021, Texas troops have sustained numerous aggressive encounters with migrants, including the discharge of weapons against civilians and allegations of human rights abuse. There is now a significant danger that this confrontational military posture on U.S. soil will be federalized, creating a dark precedent for democratic civil-military relations in the United States.

The civil-military danger goes further, though. An executive order declaring a “national emergency” at the border calls for a review of military use of force policies and a 90-day process for the Homeland Security and Defense secretaries to determine whether President Trump should invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807. That rarely used statute, an expansive exception to the Posse Comitatus Act, could allow Trump to deploy soldiers not just against migrants, but against U.S. citizens participating in political protests.

Mass deportation

A centerpiece of the Trump administration’s program is its pledge to carry out a historic “mass deportation” campaign, removing potentially millions of undocumented immigrants from the United States. This, too, would likely depend on support from the U.S. armed forces in another new and uncomfortable military role. As the Washington Post recently detailed, the primary responsible civilian agency, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), lacks personnel (5,500 Enforcement and Removal Operations agents), detention space (currently 41,500 beds), and transportation capacity (just over a dozen available aircraft) to massively deport migrants on its own. Soldiers may get called in—and in fact, four military cargo planes have now been assigned to assist deportations.

An executive order creates “Homeland Security Task Forces” to manage deportation operations in all 50 states. It calls for a dramatic expansion of detention facilities and the enlistment of state and local law enforcement to assist in the deportation effort. It calls for cutting federal funds to states and municipalities that do not fully cooperate with ICE, including those who fear that such cooperation would hobble policing in communities with significant undocumented populations. The new administration would further speed deportations by applying expedited removal in the U.S. interior. Usually used only at the U.S.-Mexico border, this procedure adjudicates claims quickly without involving an immigration judge.

Trump administration officials charged with managing “mass deportation” indicate that they will focus initially on migrants with criminal records, then expand to the larger undocumented population, which could be as many as 13 million people (over 3 percent of the U.S. population). With promises of “shock and awe” ICE raids in major U.S. cities during the administration’s first days, those officials are deliberately spreading fear in migrant communities right now.

WOLA joins the large number of migrants’ rights defense organizations alarmed by the likelihood that “mass deportation” will involve innumerable serious human rights and due process violations, including the deliberate separation of families (or, as Trump and other officials have said, the forced emigration of U.S. citizens along with their non-citizen relatives). We note the work of analysts like those at the American Immigration Council who calculate that mass deportation could cost the U.S. budget about $88 billion per year, a figure that administration officials have not disputed, and could raise inflation while shrinking the U.S. economy. We add concerns that mass deportations could drive Latin American economies into recession—the effect of a sudden increase in the unemployed population, the loss of remittance payments, and perhaps the harm done by tariffs—which, in turn, would spur more U.S.-bound migration.

Placing criminal groups on the “terrorist list”

An executive order calls for adding Mexican “cartels” (to be specified later) and two Latin American gangs—the El Salvador-originated MS-13 and the Venezuela-originated Tren de Aragua—to the State Department’s listing of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). This would be the first time that purely criminal groups—generating profits for their own enrichment instead of using them for a claimed religious or political objective—would appear on the FTO list. (The order also references the possibility of naming such groups Specially Designated Global Terrorists).

An FTO listing could free up some defense and intelligence resources to pursue these groups. However, it does not give the Trump administration the right to carry out military strikes inside the territory of a state like Mexico without that government’s consent. The 2001 “Global War on Terror” Authorization for the Use of Military Force allows such strikes only against terrorist groups with a tie to the September 11, 2001 attacks. An FTO listing would also have little effect on the penalties cartel and gang leaders already face under existing U.S. legislation, like the Kingpin Act.

Beyond its lack of practical effects, adding criminal groups to the “terrorist list” is a complicated proposal for several reasons.

- The definition of “cartel” is blurry. Groups frequently change names and fragment. Some operate like “franchises” or “brand names” with very loose command. It is rarely straightforward who is a cartel member and who is a common criminal (corner drug dealer, small-time migrant smuggler) operating with that cartel’s permission to use its “turf.” It is unclear whether corrupt officials who collude with cartels should be considered organization members.

- If Mexican cartels and other gangs become listed FTOs, “material support” provisions in the PATRIOT Act and other statutes kick in. Anyone who has had financial dealings with them or provided other support becomes a “material supporter of terrorism.” If corrupt Mexican officials face credible allegations of past cartel transactions, they become U.S. targets, or at least people with whom U.S. officials may no longer interact. The same goes for bankers, real estate brokers, and others—on both sides of the border—who may have helped launder cartel funds as well as U.S. businesses in Mexico who often have to pay extortion fees to be able to operate. While this may be a desirable anti-corruption measure, it may be more than the Trump administration is bargaining for.

- An asylum seeker fleeing threats from a cartel would become an asylum seeker fleeing threats from a listed FTO. That would strengthen their case in U.S. immigration court. However, a tragic outcome could be that people forced into making payments to cartels, like those who had to pay ransoms for release from kidnappers, or who hire a smuggler, could find themselves ineligible for asylum, as has happened in asylum cases WOLA has supported from Colombia.

- The United States has maintained a terrorist list separate from the “specially designated nationals” and kingpin lists for a reason. If the U.S. government starts to consider everyone to be terrorists regardless of motivations, then essentially nobody is a terrorist, and the post-9/11 focus on the international terrorist threat gets blurred.

Ending all federal diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility programs and mandating the recognition of only two sexes

One of Trump’s executive orders ends all federally funded DEI and DEIA “mandates, policies, programs, preferences, and activities” and all employees of DEIA offices have been put on administrative leave. Inclusion, equity, and protections for all persons who work in U.S. agencies result in better working environments and retention of professionals from all backgrounds. If people with different backgrounds and life experiences can speak and contribute freely without fear of harm at work it leads to better decision-making, informed decisions, and effective policies and programs. For work on Latin America to be sustainable and to advance, different opinions based on life experiences are needed. Cutting out all DEI and DEIA mandates sends a terrible message to Latin American countries, where a main root cause of violence and illicit economies is inequality and exclusion of groups due to class, gender, race, and ethnicity. Programming that seeks to address such disparities is needed to curb organized crime, drug trafficking, illicit economies, and out-migration.

Another of the EOs mandates a system of institutional discrimination against trans and other gender-diverse people by stating that U.S. policy will now divide all people into only two categories: male (defined as “a person belonging, at conception, to the sex that produces the small reproductive cell”) and female (“a person belonging, at conception, to the sex that produces the large reproductive cell”).

If implemented in its terms, the binary reproductive-cell-based identity system will impact everything from government-issued identification documents, to who can seek refuge at a given anti-violence shelter, to who can receive federal funding. The EO also mandates partial or total cancellation of prior government guidance on such subjects as “Creating Inclusive and Nondiscriminatory School Environments for LGBTQI+ Students,” “Confronting Anti-LGBTQI+ Harassment in Schools,” harassment in the workplace, and several support and equality measures specifically designed for intersex and trans people.

These measures increase and foment discrimination against populations already facing marginalization, stigma, and violence. The impacts will be felt beyond U.S. borders, including in Latin America, with countries copying these ideas and making the overall region more intolerant. Such intolerance can lead to conflict and violence. Foreign aid should not be conditioned with such requirements, but remain flexible so that policymakers can determine the best course of action to achieve U.S. interests.

Pausing U.S. Foreign Assistance

Another executive order would freeze all U.S. foreign development assistance for 90 days while the State Department and White House Office of Management and Budget review all programs. The goal would be to cancel and reprogram funding for aid programs that, in the Trump administration’s view, “destabilize world peace by promoting ideas in foreign countries that are directly inverse to harmonious and stable relations internal to and among countries.”

An aid freeze that leads to cuts in assistance would endanger numerous efforts in Latin America supporting U.S. goals and interests that the new administration claims to uphold. The goal of reducing U.S.-bound migration flows would be undermined by cuts to “root causes” strategies creating employment, enabling nations to integrate migrants on their own, and attacking the corruption that strengthens the criminal groups that cause many to migrate. The goal of reducing illicit drug supply is undone by cutting efforts to increase government presence in the lawless areas where such illicit drug crops are produced or to strengthen the investigation and prosecution of members of organized criminal groups. A lesson learned from the U.S.-led “Plan Colombia” effort is that addressing violence and guaranteeing security requires investment in building institutions, justice, human rights, and economic development. Pulling out those funds will be destabilizing and undermine U.S. interests. It also will open the door for other competing powers like China and Russia to fill the gap the U.S. leaves.

Exiting the Paris Climate Change Agreement

As anticipated, Trump also issued an executive order to withdraw the United States from the 2015 Paris Agreement to address climate change. U.S. withdrawal from the UN’s key climate policy coordination agreement will take effect in one year, just months after Brazil hosts the next global climate Conference of Parties in November 2025. Trump also withdrew from the Paris accord in 2017 at the outset of his first term, but President Joe Biden rejoined the agreement upon taking office in 2021. According to Trump, Paris and other international climate change agreements are unfair to the United States, and detrimental to the U.S. economy and U.S. businesses. In fact, the carbon emissions targets under the Paris Agreement are voluntary, and U.S. exit from the accord will provide opportunities for other countries, including China, to take the lead on climate policy and to shape the international environmental agenda.

Trump’s withdrawal from Paris also underscores that the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean can expect no new financing support from the Trump administration as they struggle to respond to devastating climate impacts already occurring, and to build resilience to face the even more severe crises that will inevitably arrive.Trump’s moves come despite the fact that the United States is by far the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases–having built the country’s enormous wealth by burning fossil fuels–and therefore bears significant responsibility for creating the climate crisis. By contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole have minimal historical responsibility for planet-warming emissions, but the region’s residents are highly vulnerable to climate-driven disasters. In Central America, for example, climate change is one of the leading causes of internal forced displacement in the region. For many Caribbean island states, rising sea levels–amplified by climate change–pose an existential threat.

When Trump exited Paris in his first term, no other countries followed. This time could be different. Other authoritarian and populist leaders in Latin America share Trump’s distrust of climate change policies and disdain for environmental protections. President Javier Milei of Argentina has called climate change a “socialist lie” and has threatened to remove Argentina from the Paris agreement. To be sure, simply taking part in the Paris agreement does not mean that a country has effective environmental protection and climate policies in place. But the climate agreement does create a framework that encourages countries to set ambitious climate targets and provides a basis for burden sharing, especially in terms of financing to recover from disasters and build resilience.