Throughout the nearly four years of Colombia’s negotiations with the FARC guerrillas, President Juan Manuel Santos has promised to submit a final peace accord to a vote, so that it could enjoy the legitimacy of a public mandate. This idea is commendable, but risky: polls have usually shown a solid but not overwhelming majority of Colombians supporting the peace talks, and strongly opposing key elements like alternative punishments for human rights abusers, or allowing former guerrillas to participate in politics. The possibility that a “No” vote could undo the entire peace effort is too great to be dismissed.

Santos’s proposal for a plebiscite to approve the eventual accord became law last December. The FARC accepted the idea in principle in May. It received a formal green light on July 18, when Colombia’s Constitutional Court completed its review of the law [PDF], making modest changes.

What happens next—and what might happen next—is confusing. Here, in question-and-answer form, is our understanding of how the plebiscite is likely to move forward, based on a close reading of official documents and media coverage, and conversations with Colombian experts.

When might the plebiscite happen?

It must take place at least one month, and no more than four months, from the date that President Santos notifies Congress of his intention to convene it.

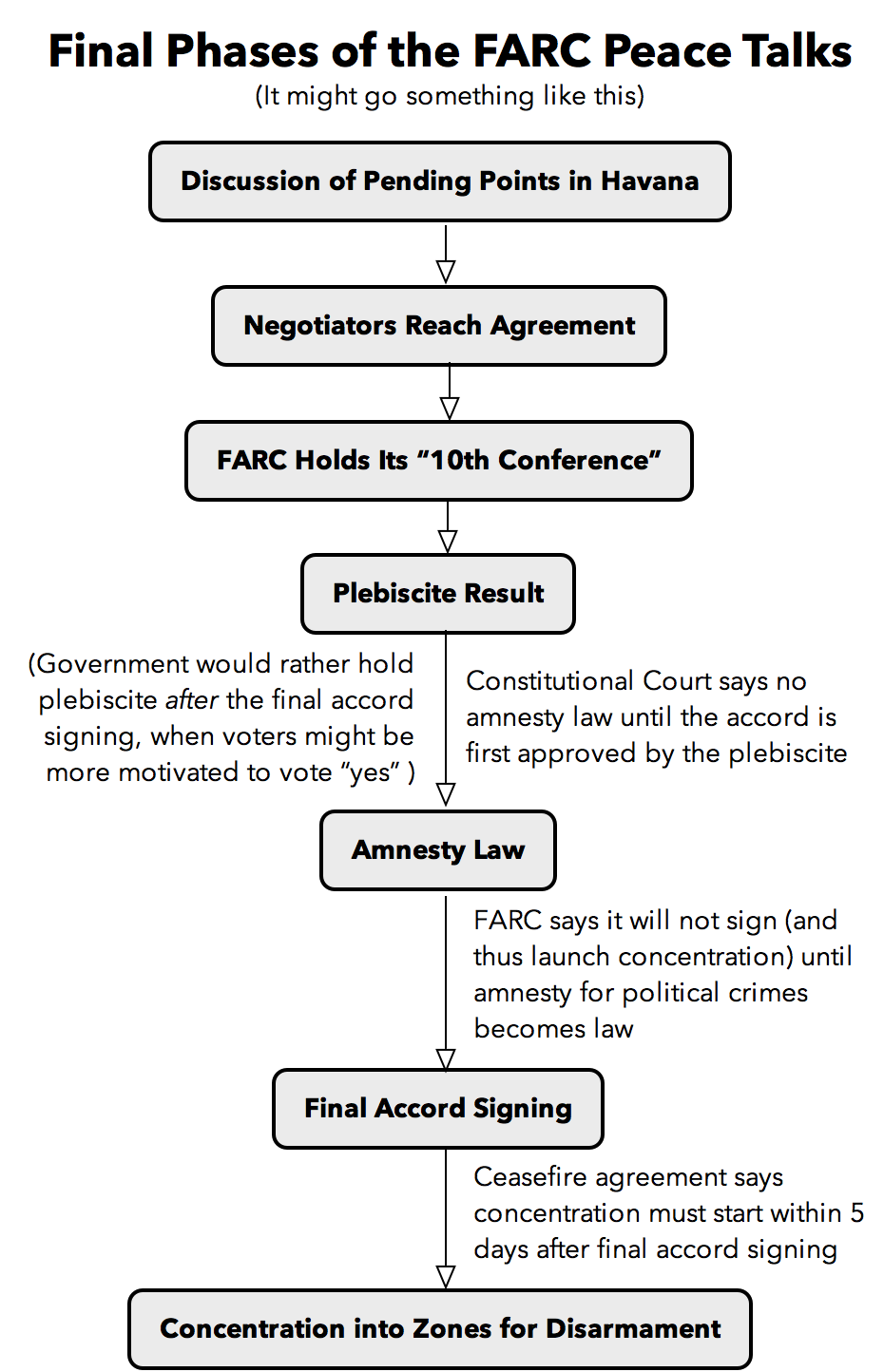

But here the timetable gets cloudy. Several things must happen in a closely orchestrated way. In order to do that, though, the plebiscite’s implementers will have to cut through some circular logic, in which B can’t happen until A is completed, yet A depends on B being completed.

The timetable could look something like this:

- Negotiators in Havana finalize the peace accord.This requires agreement on how ex-combatants will be reintegrated into society, and on several points of disagreement that the draft accordsinked since 2013 had postponed for later. (One such point—how judges will be selected for the tribunal that will decide war-crimes cases—was resolved by an agreementannounced on August 12.) Nailing down all of these questions could take several more weeks, in the most optimistic of scenarios. Once the accord is finalized, Colombia’s government must undergo a huge effort to ensure that citizens know what it says.

- The FARC leadership meets somewhere to hold its “10th Conference,” where they will discuss and make a final decision about the accord.This is necessary to guarantee mid-level commanders’ buy-in.

- Colombians vote in the plebiscite to approve or disapprove the peace accord.If Colombians vote “No,” this timeline stops. Meanwhile, in its July 18 ruling, Colombia’s Constitutional Court decreed that the amnesty law (the next step on this list) cannot be enacted unless citizens have first approved the peace accords plebiscite.

- Colombia’s Congress passes a law that, as agreed in the December 15 accord [PDF] on Victims, would amnesty the political crime of “rebellion” (sedition).Without this law, FARC members will not begin to demobilize for fear of arrest. “If there is no amnesty law, there will be no final accord,” FARC negotiator Carlos Antonio Lozada said in early August. This will not be easy either, as Colombia’s Congress must decide to what extent guerrilla fundraising activities—so-called “connected crimes” like extortion and narcotrafficking—count as “rebellion” if their purpose was to raise money for the FARC’s war effort. It is also unclear whether, at this point, Colombia would have to release thousands of FARC members serving prison sentences for “rebellion.”

- The government and FARC sign a final peace accord.This would happen at a celebratory ceremony, probably in Colombia, with many invited international delegations present.

- FARC members begin to concentrate into 23 zones and 8 encampments around the country, where they will begin a six-month, UN-verified process of disarmament and demobilization. The June 23 accord [PDF] for a cessation of hostilities and disarmament calls for the FARC to begin concentrating its members within five days of the final peace accord’s signature.

These items may not necessarily occur in this order.

For one thing, the Colombian government would prefer to hold the plebiscite after the final accord signing, so that voters are motivated to choose “Yes” during the honeymoon phase following a national celebration of peace. But the signing triggers the FARC’s concentration into zones within five days, and the FARC understandably resists leaving its members concentrated and vulnerable if Colombians end up voting “No” and nullifying the peace accords.

The FARC says its concentration into zones must await passage of a law amnestying political (not human rights) crimes. The Constitutional Court says this can’t happen, though, until voters first approve the accords in a plebiscite. In order to avoid delaying the final accord, there may be other temporary ways to give FARC members reassurance that they won’t be summarily arrested once they emerge from clandestinity. Álvaro Amaya of Colombia’s Ideas for Peace Foundation suggests that the country’s chief prosecutor could suspend or cancel arrest warrants for political crimes under the “principle of opportunity,” which rewards individuals who act to prevent a future crime.

So, the plebiscite will happen before the final accord is formally signed, and before the FARC start concentrating into zones?

That seems almost certain right now. “When we finish the agenda points, that is to say, when everything is agreed, that is when we will send the texts to Congress and convene the plebiscite,” President Santos said on August 4. “That moment won’t necessarily coincide with the signing of the accords. The signing is a formality, it can be done afterward.”

This is not optimal, because a plebiscite would be more likely to pass if it happened amid the euphoria following an accord signing, rather than during the uncertainty of the negotiations’ latter phases. But for the reasons laid out above, this looks like the most likely path.

What level of voter turnout is necessary for the plebiscite to be approved?

13 percent of Colombia’s registered voters—about 4.5 million people—must vote “Yes” (and of course outnumber “No” votes) for the plebiscite to pass. If the remaining 87 percent were to abstain from voting, the measure would still pass.

What question will Colombians vote on?

Voters will be asked, in clear language, whether they approve of the text of the final peace accord between the Colombian government and FARC. This means that the accord must be finalized and well publicized, if not yet formally signed, when the vote happens.

What will the plebiscite actually do?

A “Yes” vote will not actually change Colombian law. According to Colombia’s Constitutional Court, its effects would be to (1) bring democratic legitimacy to the final accord’s implementation effort; (2) lock the accords in so that future leaders will have to implement them “because popular approval has obligatory character,” and (3) give the parties strong guarantees that what was agreed will be complied with.

How binding is it? What happens if it gets voted down? What does the FARC do then?

The plebiscite’s result is binding on the President only, for this particular accord only. If the Colombian people vote “No,” then the President cannot implement this accord. The President could seek to negotiate a different accord with the guerrillas, or the Congress (not the President) could seek to enact this accord.

The Court explains, “A potential disapproval of the Final Accord only has an effect on the implementation of this specific public policy decision, leaving untouched the other state organs’ competencies, among them the President’s ability to maintain public order, including through negotiations with illegal armed groups, with the intention of reaching other peace accords.” An analysis in Colombia’s El Espectador newspaper adds, “The Congress, for example, could act to ensure that the accord doesn’t die. There is also the possibility that, through a legislative act, the Congress could restore the President’s ability to do it,” thus overturning the plebiscite.

Those scenarios are unlikely in real life. A ballot-box rejection could be a fatal blow to the government-FARC negotiation. The accord—and perhaps the very idea of negotiating—would lose legitimacy, after more than four years of negotiations. President Santos could insist on carrying the implementation process forward, but against a showing of popular disapproval, the probability that local governments—or the next president—would implement the accords is small.

This would be brutal. “If the public says ‘No,’ the process stops and there will be no result,” chief government negotiator Humberto de la Calle told Colombia’s El Tiempo newspaper. “We would have lost, quote unquote, ‘four years of our lives.’”Added former President César Gaviria, who is heading the campaign for the “Yes” vote: “The consequence of ‘No’ winning is war.”

There is always the possibility that the FARC leadership could continue the process despite the plebiscite result. “If ‘No’ wins, it wouldn’t mean that the process has to fall apart,” guerrilla negotiator Carlos Antonio Lozada said in late June. “We aren’t required by law to decide to continue such a painful war.” That, at least, is the view of top FARC leaders in Havana. It is a different question whether FARC fronts and blocs in the field would feel the same way, and especially whether they would trust the government’s security guarantees if the accords are rejected.

What are the polls saying?

In the weeks after June 23, when the government and guerrillas signed a definitive ceasefire accord, a solid majority of poll respondents said that they would vote “Yes” in a plebiscite. (Gallup [PDF] 70 percent “Yes” to 17 percent “No”; Cifras y Conceptos 74 percent “Yes” to 19 percent “No.”; Ipsos 56 percent “Yes” to 39 percent “No”)

More recent polls, though, show a big decline in “Yes” voters. A cover story in the August 7 issue of the newsweeklySemana sent a shiver through Colombia’s political class. It featured a poll showing a 17-point drop in support for “Yes” between late June and early August. The Ipsos survey showed “No” leading “Yes” by a 50-to-39 percent margin. A few days later, El Tiempo released a Datexco poll showing “Yes” leading “No” by 32.7 percent to 30.4 percent, with 23.6 percent of respondents undecided.

Why the decline in support?

Viewed outside Colombia, the sharp drop in support for the “Yes” vote makes little sense. Though a final accord is still forthcoming, nothing bad has happened in the peace process. Subcommittees are ironing out final points, protocols for disarmament have been developed, and the UN monitoring and verification mechanism is getting organized.

Instead, the reasons for the drop in support for “Yes” have more to do with Colombian domestic politics.

- President Santos is unpopular, and is dragging the vote down with him.Colombia’s commodity-dependent economy is sputtering, with unemployment back up to double digits. Government messaging on a range of issues has been unfocused, with little message clarity, allowing political opponents to dominate news coverage. And Santos—who is much more of a political tactician than a populist—inspires little empathy among the average voter. His approval ratings are very low: 25 percent in the Ipsos poll, 30 percent in the Gallup poll.

During the 2014 presidential campaign that led to Santos’s re-election, pundits often remarked that the vote was a sort of referendum on whether to continue with the FARC peace process. Now that the peace process is nearing its end, the peace plebiscite is in danger of becoming a referendum on Juan Manuel Santos.

- President Santos’s predecessor and fiercest political opponent, Álvaro Uribe, is leading the charge for the “no” vote.Uribe, now a senator and head of a rightist opposition party, is Colombia’s most popular politician right now, though the polls don’t give him astronomical approval ratings (Ipsos 54 percent, Gallup 59). He is also Colombia’s most vocal critic of the peace agreements with the FARC, which he characterizes as a concession to terrorism, an insult to the armed forces, and a step toward Colombia being led by a leftist ideology he calls “Castro-Chavismo.”

Uribe is a master at giving strongly worded, headline-generating statements, both on television and on Twitter, and he has been dominating news cycles in Colombia’s non-print media. He and other supporters of the “No” option have been cranking out messages for weeks, while the “Yes” camp—in part awaiting legal clarity about whether officials could campaign, in part busy ironing out accord and disarmament details—has been late to the fight.

For now, the plebiscite’s final outcome is as uncertain as its timetable.