Contents:

- Overlapping crackdowns have cut U.S. border authorities’ migrant encounters

- All nationalities declined this summer, especially families from Mexico

- Texas’s state government crackdown has not reduced or deterred migration

- Weekly data indicate that the drop in migration is plateauing

- More migrants are dying in El Paso even as migration drops

- CBP One appointments are not increasing, worsening backlogs in Mexico

- Releases from Border Patrol custody have dropped sharply

- Use of Expedited Removal has hit record levels

- Venezuelans, Cubans, and Haitians have turned almost exclusively to CBP One

- The geographic diversity of migration continues to expand

- Darién Gap migration has dropped too, for now

- New Mexican visa requirements have cut air arrivals from Peru, but may increase Peruvian migration in the Darien Gap

- Conclusion

Migration to the U.S.-Mexico border has plummeted in 2024: this summer has seen some of the fewest migrant arrivals in four years. While this might suggest that migration is now “under control,” a closer look at the data reveals a stark humanitarian cost as enforcement policies grow more aggressive in the United States, Mexico, and further south.

The numbers show that more migrants and asylum seekers are being denied protection, often bottlenecked along the route and preyed upon by criminal groups, while deaths on U.S. soil increase. The numbers contradict the narratives of hard-liners, like the state government of Texas, who insist that harsh crackdowns on protection-seeking migrants are effective. And they offer no evidence that the present migration decline will be long-lasting.

Instead, ten years of repeated crackdowns have failed to limit migration for more than a matter of months, and the current push is unlikely to yield a different outcome. There are a few reasons for this:

- At a time of historically high global migration, the underfunded, overloaded, unreformed U.S. asylum system has become the only choice for many fleeing their countries, as antiquated U.S. immigration laws leave almost no legal migration pathways.

- The causes of high migration levels—government repression, threats from organized crime, generalized criminal violence, poverty, the climate crisis, gender-based violence, discrimination, and failure to integrate migrants elsewhere in the region—remain robust.

- Factors that facilitate the journey, like corruption and states’ abdication of territory to criminal groups that engage in smuggling, have barely changed.

The data tell us a lot about the impact that harsher policies, and an underlying lack of basic immigration and asylum reform, are having right now on migration at the U.S.-Mexico border and along the U.S.-bound route. Here are 12 important points and trends.

1. Overlapping crackdowns have cut U.S. border authorities’ migrant encounters

The most recent data comes from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which released information on August 16 about the agency’s encounters with migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border through July 2024.

- In July, CBP encountered migrants 104,116 times, the fewest since February 2021, the Biden administration’s first full month in office.

- Of that number, 56,408 were Border Patrol apprehensions of people who crossed the border without inspection between ports of entry, the official border crossings. (See the chart below.) That is the fewest Border Patrol apprehensions since September 2020—during the Trump administration and the COVID pandemic’s first months.

- The remaining 47,708 entered CBP custody at the ports of entry. Most were asylum seekers: about 38,000 had made appointments at the ports using the “CBP One” smartphone app.

Border crossings have dropped sharply as an immediate result of two overlapping 2024 crackdowns on migration, which have been especially hard on migrants seeking protection. First, since the beginning of the year, the government of Mexico has stepped up aggressive efforts to block migrants, busing tens of thousands of them to the southern part of the country. That caused migration between ports of entry to drop by 50 percent from December 2023 to January 2024.

U.S. border authorities’ migrant encounters remained near that lower level from January to May, some of the months of lightest migration at the border during the Biden administration. Then, in early June, the administration launched a second crackdown: a proclamation and rule refusing asylum to most people who cross the border between ports of entry during busy times. At least for now, the additional measure has cut migration in half again: a 52 percent drop in Border Patrol apprehensions from May to July 2024.

Border Patrol is rapidly removing those who make it across Mexico but do not schedule an appointment at a port of entry using the “CBP One” smartphone app—either because their protection needs are too urgent to allow them to endure the months-long wait, or because they are not aware of this requirement. (As noted in item 6 below, these appointments are limited and CBP is not moving to increase them.)

U.S. law states that people who fear return to their country have the right to seek asylum if they are on U.S. soil, regardless of whether they crossed at a port of entry or whether they crossed “improperly.” The June 2024 rule, however, has suspended that right during busy periods, with hard-to-attain exceptions for those able to prove they face the most immediate danger.

July’s Border Patrol apprehensions were 77 percent fewer than last December’s, but the cost has been tens of thousands of people stranded in Mexico and untold numbers of people who need protection being denied it. Reports from non-governmental organizations and media, including two updates from coalitions of U.S. and Mexican groups, are documenting mounting abuses against people deported into Mexico, or enduring prolonged waits for CBP One appointments. These include rough treatment from U.S. and Mexican migration officials; family separations; kidnappings for ransom in Mexico; assaults and theft from criminals and corrupt officials in Mexico; racial, gender, and LGBTQ+ discrimination; squalid living conditions; denial of urgent health care; and increasing migrant deaths on U.S. soil (see item 5 below).

2. All nationalities declined this summer, especially families from Mexico

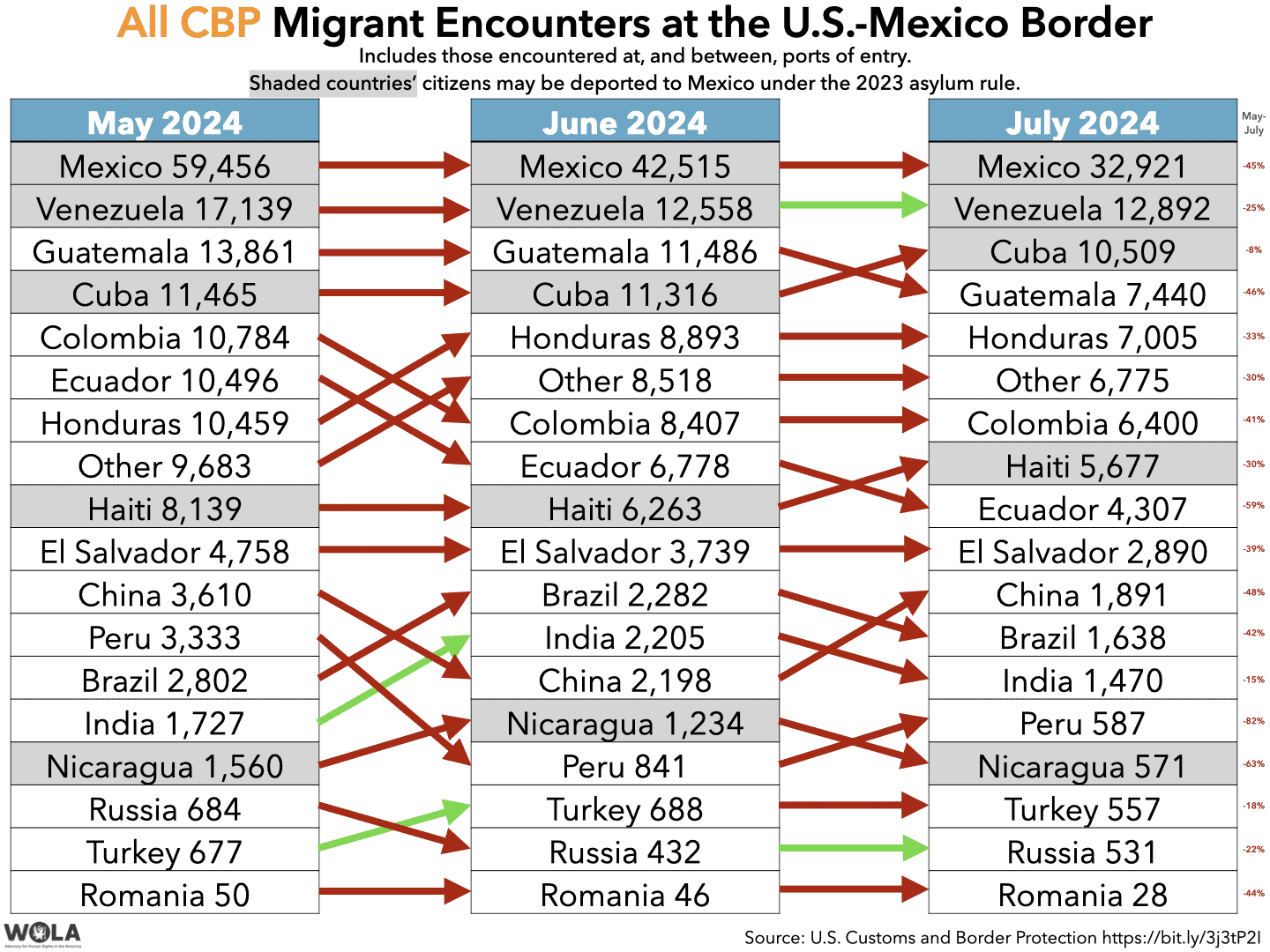

Combining Border Patrol apprehensions and port-of-entry arrivals, CBP’s migrant encounters dropped 39 percent from May to July. Encounters with citizens of Peru (-82%), Nicaragua (-63%), and Ecuador (-59%) dropped most sharply. (See item 12 below about Peru.) Encounters with citizens of Cuba (-8%), India (-15%), and Turkey (-18%) dropped the least.

Mexican families, many from violence-plagued states like Michoacán, Guerrero, Sonora, and increasingly Chiapas, had begun arriving at the border in greater numbers during the second half of 2022, turning themselves in to U.S. authorities. By December 2023, a single-month record 37,285 members of Mexican family units came to the border, 80 percent of them between ports of entry.

By putting the asylum system out of reach between ports of entry, the June asylum ban reduced arrivals of Mexican family members by 60 percent: from 27,500 in May to 11,127 in July. (49 percent of July’s family members came to ports of entry.) Like other nationalities, Mexican people seeking protection must make CBP One appointments, which usually requires waits of several months inside Mexico. Unlike other nationalities, though, Mexican people are waiting inside the same country where they are threatened, which endangers them.

3. Texas’s state government crackdown has not reduced or deterred migration

CBP’s data shows recent movement toward Arizona and California, with Border Patrol’s San Diego, California, sector leading all others in migrant apprehensions for the first time in over 25 years. At first glance, it might appear that the state government of Texas under Gov. Greg Abbott (R), which has pursued a series of high-profile, hardline measures against migrants, is pushing migration elsewhere. Some of Abbott’s own statements have made that claim.

But a look at the data reveals that this is not happening. All states are seeing declining Border Patrol apprehensions, and Texas’s rate of decline is typical, despite the state government’s multi-billion-dollar “Operation Lone Star” border crackdown.

Looking at Border Patrol apprehensions by state reveals that Texas has not experienced a steeper migration decline than Arizona, where the Democratic governor has not pursued similar hard-line measures.

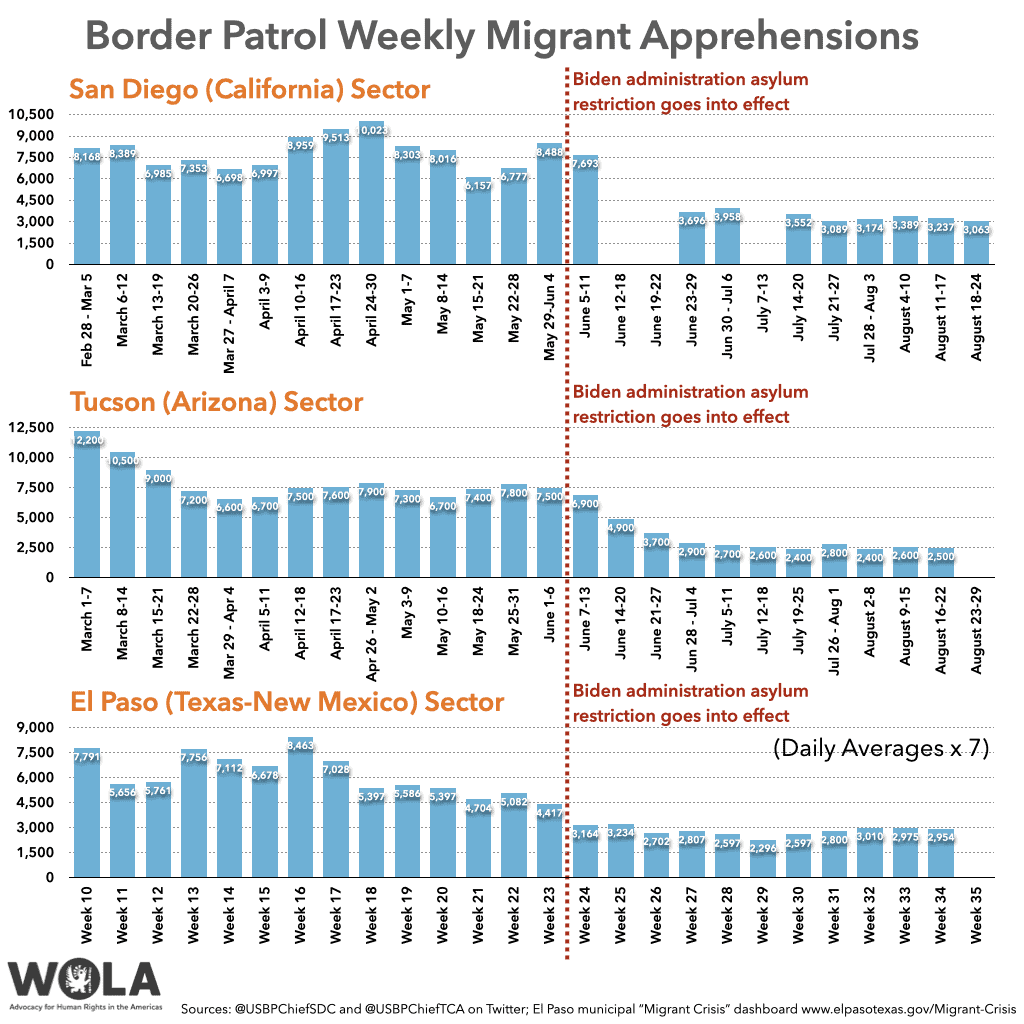

4. Weekly data indicate that the drop in migration is plateauing

The Biden administration asylum rule’s early-June rollout caused arrivals of migrants between ports of entry to drop sharply for a few weeks. But by early July, those drops had ceased, and the rate of decline has since smoothed out to near zero.

This pattern of a sharp drop followed by a period of stagnation is familiar from past border crackdowns, like Mexico’s mid-2010s “Southern Border Plan,” the Trump administration’s 2017 arrival in power, or the pandemic-era Title 42 expulsions policy and its expansions. Migrants and smugglers go into a sort of “wait and see” mode as they learn how the new policy is being implemented. After migration “bottoms out,” it begins to recover and rise again, usually after a few months.

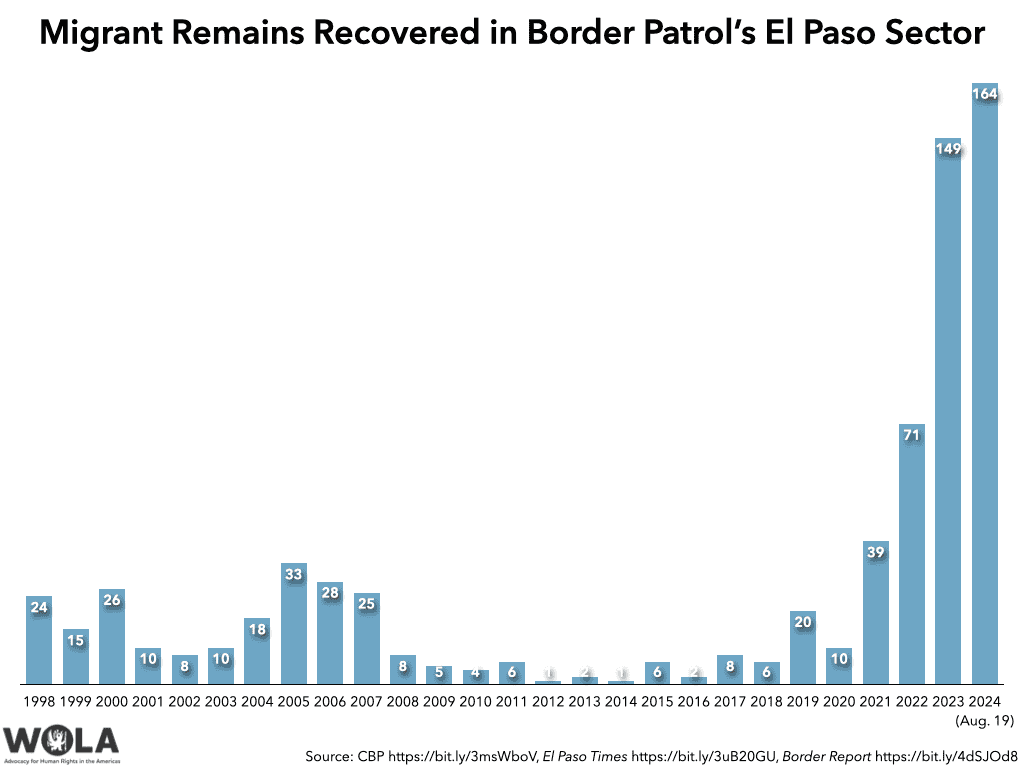

5. More migrants are dying in El Paso even as migration drops

Border Patrol’s El Paso Sector (far west Texas and New Mexico) has seen apprehensions drop 35 percent since 2023 (comparing an average month last year to an average month in this still-incomplete year). Alarmingly, though, deaths in this sector—the only one for which we have seen current data—are not dropping along with overall migration. They are increasing.

The death toll—mainly from heat exhaustion and dehydration, plus a few falls from the border wall—is still growing during a very hot summer in the Chihuahuan Desert. It is reaching a height that was unthinkable in a sector where Border Patrol had never recovered more than 32 migrant remains in a year before 2021. Border Report, citing Border Patrol, reported 164 remains recovered in the sector as of August 19, with six very hot weeks remaining in the 2024 fiscal year.

It is difficult for asylum-seeking migrants to access the U.S. asylum system in El Paso. The Biden administration asylum rule has made port-of-entry appointments via the CBP One app the only real option, yet the sector offers just 200 appointments per day.

Some asylum seekers might try to cross the narrow Rio Grande and turn themselves in to Border Patrol anyway, hoping to pass one of the new rule’s more stringent credible fear interviews. However, because Texas’s state government has arranged concertina wire in front of the border wall, with state police and National Guardsmen carrying out illegal orders to push asylum seekers back into Mexico, successfully crossing is next to impossible. For that population, the treacherous desert route may seem to be the only option.

Deaths appear to be concentrated in areas that are a short drive from El Paso and other populations where water and first aid would be available. Most should be preventable. “The stretch of desert south of NM State Road 273 (McNutt Drive) and south of NM 9 (Columbus Highway) has become a graveyard,” wrote Julián Resendiz of Border Report.

Here is that area on a map created by No More Deaths, which recently began keeping a database of recovered remains in the El Paso sector. This map covers less than 35 miles from its western to eastern edge.

6. CBP One appointments are not increasing, worsening backlogs in Mexico

The Biden administration’s rule-making has made it so that turning oneself in to Border Patrol is no longer an option for accessing the U.S. asylum system, with very few exceptions. Yet the only remaining route for most, CBP One appointments, has not expanded.

CBP has not adjusted the number of available appointments since June 2023. The border-wide maximum is 1,450 per day. In the vast area between Calexico, California and Eagle Pass, Texas—nearly half of the border’s miles—there are just 300 appointments per day.

Before the Biden administration shut down asylum access for those crossing between ports of entry, the U.S. government invested hundreds of millions of dollars into building up Border Patrol’s capacity to process asylum seekers who came into the agency’s custody. Some Border Patrol sectors have giant processing centers, staffed with several hundred newly hired processing coordinators. Today, these facilities are standing nearly empty, even as the ports of entry receive 1,450 asylum seekers per day.

This calls for creative and humane solutions, like busing asylum seekers from the ports of entry to the empty nearby Border Patrol processing sites, which would allow an expansion of CBP One appointments, thus reducing wait times in Mexico.

7. Releases from Border Patrol custody have dropped sharply

At the U.S.-Mexico border in December 2023, Border Patrol released 191,782 apprehended migrants into the U.S. interior with “notices to appear” (NTAs) in immigration court, usually with asylum claims. (Nearly all of the rest were deported, placed in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention, or—if they were unaccompanied minors—transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement.) That was 77 percent of the record 249,741 migrants whom the agency apprehended between ports of entry during that record-setting month.

Due to strict implementation of the Biden administration’s asylum ban, releases from Border Patrol custody have plummeted: 12,110 people received NTAs or paroles in July 2024, 94 percent fewer than last December and the fewest since January 2021, the month of Joe Biden’s inauguration. Only 21 percent of migrants apprehended between ports of entry in July were released, the smallest percentage since January 2021.

8. Use of Expedited Removal has hit record levels

Nearly half of migrants apprehended by Border Patrol in July 2024 (27,313 of 56,408, 49%) were placed in expedited removal proceedings, a rapid process for deporting people without giving them hearings, usually while they are still in custody at the border. That is the largest monthly percentage ever of apprehended migrants placed in expedited removal.

The law requires that those in expedited removal who express fear of return get a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer. The Biden administration’s June rule states that U.S. border authorities need not offer this opportunity to migrants who fail to speak up and specifically express fear. Yet even when they do express fear, border agents on many occasions are ignoring or rejecting their pleas, according to groups monitoring conditions at the border since the rule went into effect.

9. Venezuelans, Cubans, and Haitians have turned almost exclusively to CBP One

- Since fiscal 2020, 77 percent of Venezuelans who have crossed the border have done so between the ports of entry, ending up in Border Patrol custody (570,062 people). In July 2024, however, only 5 percent of Venezuelans crossed between the ports (612 people); the rest came to the ports, nearly always with CBP One appointments.

- Since fiscal 2020, 73 percent of Cubans have arrived between the ports of entry (397,831 people). In July 2024, however, only 1 percent of Cubans crossed between the ports (105 people); the rest came to the ports.

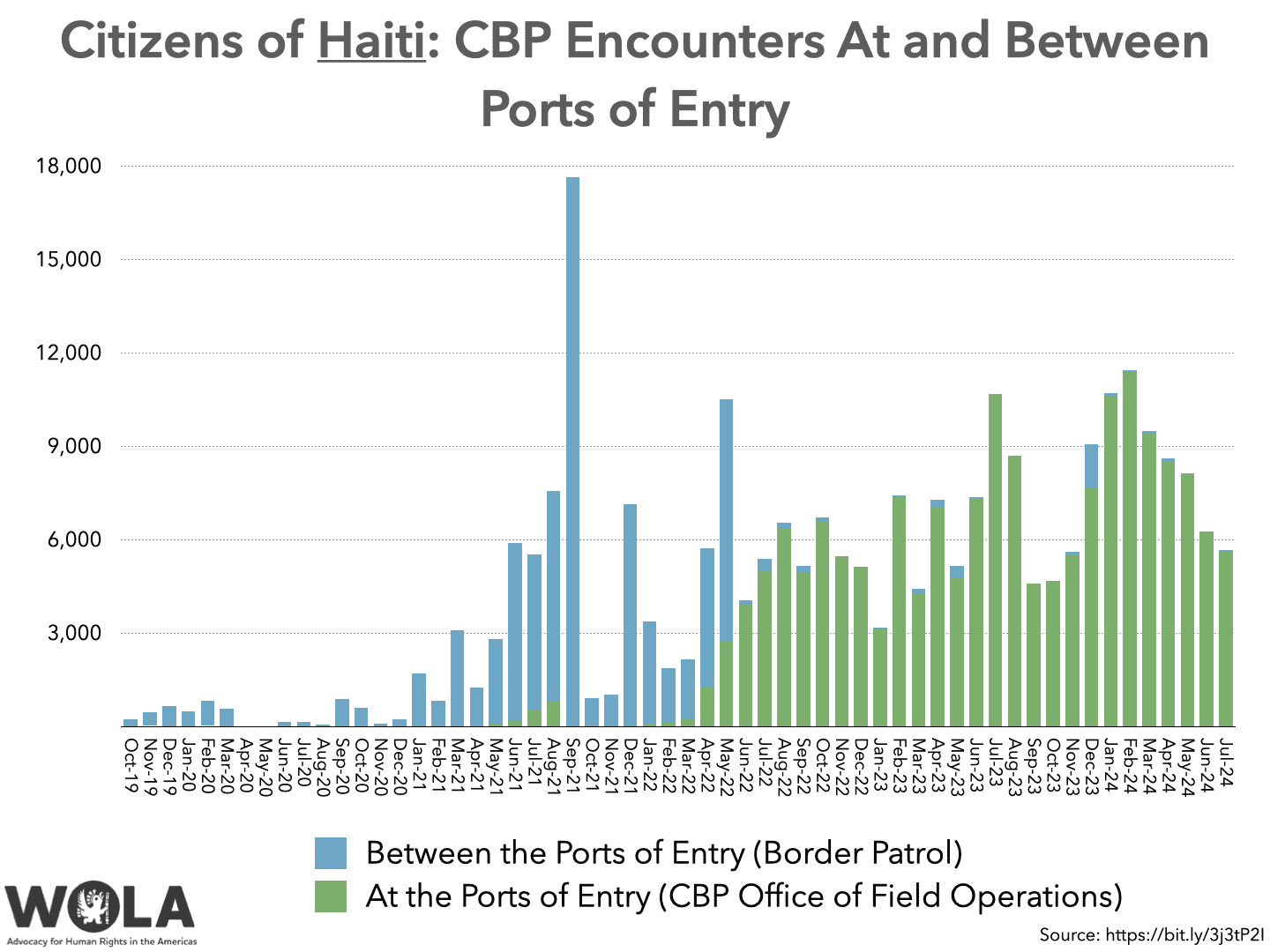

- Since fiscal 2020, 31 percent of Haitians have arrived between the ports of entry (81,934 people). In July 2024, however, only 1 percent of Haitians crossed between the ports (64 people); the rest came to the ports.

There is a clear reason for this shift. If they cross between the ports of entry, these nations’ citizens may be deported into Mexico, not even their home countries, without a chance to seek asylum. (This also applies to citizens of Nicaragua, whose entries have declined regardless of how they arrive.) Mexico has agreed to accept land-border deportations of up to a combined 30,000 people per month from these four countries.

While the Biden administration has offered a “humanitarian parole” status to the same monthly number of those countries’ citizens who apply online, that process requires applicants to have a passport and a U.S.-based sponsor, which excludes many of the poorest and those who need to flee most urgently.

(Data table for port of entry encounters – all migrant encounters)

(Data table for port of entry encounters – all migrant encounters)

Data table Data table |

Data table Data table |

Data table Data table |

10. The geographic diversity of migration continues to expand

Border-wide through April, 11 percent of migrants apprehended by Border Patrol in fiscal 2024 (which began last October) were from Europe, Asia, or Africa—not the Americas. That has never happened before: 2023 saw a record 9 percent, which in turn broke a 2022 record of 4 percent.

11. Darién Gap migration has dropped too, for now

Panama’s new president, José Raúl Mulino (inaugurated on July 1), promised as a candidate to crack down on U.S.-bound migration through the Darién Gap, a vast, little-governed jungle region straddling Panama and Colombia. Upon taking office, Mulino ordered a few miles of barbed wire laid along some frequently traveled routes through the Darién and, with U.S. financial backing, has now launched a program of deportation flights that appears to aim to operate at a tempo of three or four planes per week.

That alone won’t deter Darién Gap migration, especially if turmoil and repression following Venezuela’s July 28 elections bring a new wave of migration. But it is enough to place would-be migrants (and smugglers) in a “wait and see mode” as they evaluate these new measures’ impact.

The crackdown, along with recent visa suspensions for some Asian nations’ citizens who begin their overland journeys in Ecuador and Brazil, has led the number of migrants making the several-day journey through the Darién to plunge to levels not seen since April or May 2022. Panamanian migration officials shared with reporters an August 25 release informing that they had measured 9,497 people emerging from the Darién Gap route during the month’s first 24 days: about 396 people per day. That is far less than the daily average for the first six months of 2024 (1,105) and the more than 2,000 per day who traveled this route in August and September 2023.

As with all “wait and see” responses to news of a crackdown, this is almost certainly a temporary lull, as the drivers of migration continue (and in Venezuela, are intensifying) and the Darién wilderness remains very difficult to control. Migration is likely to increase again in a matter of months.

12. New Mexican visa requirements have cut air arrivals from Peru, but may increase Peruvian migration in the Darien Gap

Peruvians were the nationality whose Border Patrol apprehensions declined the most from May to July. Combining Border Patrol apprehensions and port of entry arrivals, just 587 Peruvians came to the U.S.-Mexico border in July, down from 3,333 in May: an 82 percent drop in 2 months. (The April to July drop was even steeper: 91 percent.)

While the Biden administration asylum rule was a factor, Peruvian arrivals declined mainly because Mexico, in early May, began requiring visitors from Peru to have a visa. Before then, Peruvians could arrive in Mexico by air without arranging for a visa ahead of time. Many, the data indicate, traveled from there to the U.S. border and turned themselves in to U.S. authorities. With that route closed off, the number of Peruvians at the U.S. border plummeted.

This change is likely to have grave unintended consequences. Within a few months, we should expect to see a sharp increase in the currently low number of Peruvian citizens migrating through the Darién Gap.

We have seen this before. Mexico blocked visa-free air travel of Ecuadorians in September 2021, and of Venezuelans in January 2022. Within a few months, both nationalities’ presence in the Darién Gap skyrocketed; even now, in 2024, they are the number one and number three nationalities passing through the Darién.

|

|

Conclusion

The Biden administration and Democratic candidates have been aware that the border and migration were a public opinion vulnerability heading into the 2024 election campaign. They appear satisfied that the recent drop in migration numbers at the border, resulting from Mexico’s crackdown and new asylum restrictions, has blunted a Republican line of attack.

The present reduction is a short-term phenomenon. It is likely to reverse in a matter of months as the conditions and root causes for migration remain the same.

The administration and allied candidates should have no illusions that the reduction is consequence-free. The choices that brought it about carry a painful human cost. Thousands are stranded and exposed to exploitation, violence, and life-threatening conditions, and even death if they decide to migrate in hazardous regions.

The next administration must act to adapt the U.S. immigration system to the reality of the past 10 years. Making processing, case management, and adjudication more efficient would slash wait times for asylum decisions while strengthening due process. But ultimately, people request asylum because it is the only legal option available to them. It is urgent to expand other legal pathways, too, like temporary work visas, humanitarian parole, refugee admissions, family reunification programs, and citizenship pathways. That is the only viable way to guarantee rights while breaking out of this frustrating cycle of ever-harsher crackdowns.