Rarely considered a priority region for U.S. foreign policy, Latin America has come to the forefront during the first few months of President Donald Trump’s second term. Deep cuts to U.S. assistance, threats to resume U.S. control over the Panama Canal and to intervene militarily in Mexico, the imposition of steep tariffs on Mexico as well as Canada and subsequently throughout the world, and the in some cases unlawful outsourcing of U.S. immigration and protection responsibilities, confront Latin American countries with a complex new era of engagement with the United States. At home, the administration’s relationship with El Salvador’s authoritarian-trending government lies at the heart of one of the most severe constitutional crises in modern U.S. history.

President Trump has launched his second term at a frenetic pace, issuing more than 135 executive orders in the first hundred days. This torrent of presidential directives has touched virtually every aspect of the federal government, part of a deliberate strategy to “flood the zone” and stay on the offensive. The administration’s actions have already brought massive changes to U.S. foreign policy.

Apart from drastic cuts to U.S. foreign assistance and the decimation of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Trump’s proposed restructuring of the State Department would eliminate 132 agency offices, with democracy and human rights promotion hit especially hard. The State Department’s annual human rights report–which was mandated by Congress in 1975 through amendments to the Foreign Assistance Act and in 1979 was expanded to include all countries –would be “streamlined,” apparently dropping references to diversity, equity, and inclusion, sections on government corruption, the rights of women, the disabled, and LGBTQI+ community, as well as on governments denying freedom of movement and peaceful assembly. Trump’s team is disbanding federal climate efforts within U.S. domestic and foreign policy while also dismantling diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, leaving vulnerable communities unprotected.

At the same time, with the U.S. borders closed to asylum seekers and no refugee admissions into the country, tens of thousands of people in need of international protection have been left stranded, with others being unlawfully sent, and even imprisoned, in third countries. Trump officials have also made clear the administration’s disdain for the United Nations and international law, which they view as illegitimate constraints on U.S. sovereignty and power. Combined, these steps signal a dramatic retreat from the long-professed U.S. role of supporting human rights and democracy worldwide and could have repercussions for decades to come.

While the administration’s moves have been welcomed by Latin American leaders considered “friends” of the new administration, Trump’s whirlwind of statements and actions in these early months of his second term have been met with trepidation and dismay by others, including civil society and press freedom organizations throughout the region. Many such organizations have not only lost crucial U.S. funding, but now fear that the Trump administration will either sit silently instead of denouncing attacks against them or even worse, voice U.S. support for governments that are wielding their power against civil society.

Trump’s team has not yet presented Congress with its fiscal year 2026 budget proposal laying out the new administration’s foreign assistance priorities. When Congress does take up the FY2026 spending bills, including appropriations for foreign assistance, the debate will unfold in the midst of enormous uncertainty: The Trump administration has shown no commitment to abide by funding directives mandated by Congress, while congressional Republican leaders have largely remained silent on the cuts to foreign assistance and dismantling of USAID. Below, WOLA lays out some of the most significant impacts on Latin America of Trump 2.0’s early days. Read our executive summary here.

Friends and adversaries in Latin America

When recently asked about the administration’s perceived pivot towards the Western Hemisphere, Secretary of State Marco Rubio singled out countries in the region viewed as friends of the United States and the belief, mirrored by other Republican leaders in Congress, that these leaders were too often ignored by a Biden administration that was at the same time too lenient on U.S. foes. “[F]or a long time if you were a U.S. or pro-American ally in the region, we kind of ignored you and in some cases actually treated you bad … [W]e made deals with the people that hated us and we either neglected or sometimes were outright hostile towards the countries that were pro-American. So we’ve reversed all of that.”

Countries mentioned by Rubio as friends include Guyana, Argentina, Paraguay, Costa Rica, Panama, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic. Other countries, such as Mexico, where the administration has some “tough issues to work through,” are likely somewhere in the middle. Although not explicitly mentioned, Guatemala’s government also appears to be enjoying favorable relationships with the Trump administration, based on Rubio’s positive February visit with President Bernarndo Arévalo, as is recently re-elected President Daniel Noboa of Ecuador. Argentina’s President Javier Milei, whose ideology and worldview strongly align with Trump’s, remains a close ally, even though the country was hit with a 10 percent tariff, along with virtually every other country in the world. While Colombia remains key to U.S. interests, relations with President Gustavo Petro are strained, as evidenced by the ugly Petro-Trump fight on X, which escalated quickly in January.

The Trump administration’s approach to the three countries Rubio has singled out as enemies of humanity–Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela–has been confusing. On the one hand, it has taken a tough stance: reversing, as was expected, the Biden administration’s last-minute policy changes on Cuba, including by placing the country back on the state sponsors of terrorism list; adding 250 Ortega-Murillo regime officials to its list of U.S. visa restrictions covering Nicaragua; and revoking licenses to export Venezuelan oil to the United States while also imposing tariffs “on all goods imported into the United States from any country that imports Venezuelan oil, whether directly from Venezuela or indirectly through third parties.”

Beyond these measures, the Trump administration appears to have no clear roadmap to support human rights or to find paths toward democratic transitions in these countries. At the same time, the Trump administration has curtailed legal protections for citizens of these repressive regimes who recently arrived in the United States, including attempting to cancel the status of all those who entered under the Cuba, Venezuela, Haiti, and Nicaragua humanitarian parole process and to end Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans. Both of these efforts have been stayed by U.S. courts but the administration’s attempts to end these legal pathways indicate no real concern for sending people back to countries led by “enemies of humanity” in order to fulfill Trump’s campaign promise of mass deportations.

More recent interviews with Rubio also point to a differentiated focus of U.S. foreign policy, not only favoring those who are pro-U.S. with like-minded conservative views, such as restricting access to abortion and curtailing support for diversity and the protection of vulnerable groups, but also what is considered in the U.S. national interest, led by an “America First State Department.” In the case of Central America, for example, Rubio has commented, “It’s migration, it’s drugs, it’s hoping to have countries that are prosperous so people don’t migrate here and don’t join drug cartels.” The same might also be said about Mexico and elsewhere. Regardless of the country, what does seem clear is that the Trump administration no longer sees human rights as a priority for U.S. foreign policy, whether through diplomacy, reporting, or assistance.

A militarized campaign of fear against migrants

A vicious animus toward migrants has been the largest motivating factor behind the Trump administration’s foreign policy toward Latin America so far. The first 100 days have been marked by an intensifying campaign against a vulnerable population whose economic contributions to the United States are disproportionately large, and whose responsibility for crimes committed in the United States is disproportionately small.

Migrants in the United States, including many with documented status and mixed-status households, are living in fear. The vast majority of the undocumented in the United States, an estimated 11 million in 2022, are from Latin America (7.87 million), as are the precariously documented recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), Temporary Protected Status holders, and recipients of humanitarian parole.

And the promised mass deportation offensive has not yet begun in earnest. That won’t happen until the administration has the money and the personnel to carry it out. Doing that will require the Republican-majority Congress to pass a stunningly massive funding bill, which it will do under a rarely invoked rule called “Reconciliation” that will allow it to pass without a single Democratic vote. It may also mean embarking on what could be the largest internal mission, on U.S. soil, for the United States military since the Civil War.

The reconciliation bill will begin moving through Congress during the final days of April. We haven’t seen all the details yet, but we know that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) may get as much as USD$175 billion to spend on border-hardening and mass-deportation initiatives over the next 10 years, most of which will be front-loaded into the next few years. That average annual amount of $17.5 billion is more than today’s combined annual budgets of ICE and Border Patrol. We already know that ICE is seeking contractors for $45 billion worth of detention capacity over two years, six times the current budget. And the reconciliation bill could include many billions more for mass deportation in the budgets of the Departments of Defense and Justice.

Even at current funding levels, arrests of migrants—over half of them without any criminal convictions—have sharply increased all around the country. ICE’s privately managed detention centers are already well over 110 percent capacity, and “family detention” facilities have reopened. Though litigation has at least temporarily achieved important blocks, detention and deportation machinery may be fed by the administration’s abrupt cancellations of documented statuses granted by the Biden administration, including humanitarian paroles, paroles for people who made “CBP One” appointments at border ports of entry, and Temporary Protected Statuses.

The administration has effectively shut down the asylum system at the U.S.-Mexico border, in violation of the Refugee Act of 1980, which mandates that people on U.S. soil who express fear of death or persecution have a right to due process. An executive order seeks to justify that with a spurious claim, currently being challenged in courts, that migrants—who are leaderless, unorganized, unarmed, and usually have humanitarian needs—somehow constitute an “invasion.” The disappearance of asylum has meant a sharp, artificial drop in the number of asylum seekers apprehended at the border, which the administration’s supporters and even some simplistic media coverage have been portraying as a “success.”

In order to spread fear further among the migrant population, during its first 100 days, the administration began sending citizens of countries to which deportation is difficult to third countries. Thousands of non-Mexicans have been pushed across the border into Mexico. Two hundred people from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe were unlawfully sent to Costa Rica, and 299 more people from these regions were sent to Panama, despite protection needs. Two months later, over 200 remain in those two countries in a precarious status because they fear for their lives if returned to their home countries.

To that, of course, must be added the 288 people—that we know of—from Venezuela and El Salvador who are now in El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, sent there from ICE detention without ever having received due process, with no hope of release or contact with the outside world, and no end date for their illegal confinement. Many of the Venezuelans were asylum seekers, and the administration has yet to present any evidence of their criminal activities in the United States. The administration invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 for only the fourth time in history to send 137 of the Venezuelans without due process, defying a judicial order. The other migrants had final removal orders and while U.S. law does not prohibit third-country removals in some cases, no law allows them to happen without evaluating protection needs, and absolutely no law allows for indefinite, extrajudicial transfers to foreign prisons.

The list of known innocent victims of these renditions is long. It includes Kilmar Abrego García, a Salvadoran father of three from Maryland, whose expulsion ICE has even admitted was an error, but who the Trump administration is now slandering as a terrorist, refusing to extract him from El Salvador. It includes Andry Hernández Romero, a gay Venezuelan makeup artist, apparently rendered to the CECOT because he had tattoos reading “Mom” and “Dad.” Still, the administration clings to a story that these and many more individuals have violent gang ties, without producing a shred of evidence.

And then there are the more than 400 people who, for no apparent reason other than to spread fear within the migrant community, the Trump administration has sent to the U.S. military base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, at a reported cost of more than $40 million. While most have been moved out, about 40 remain. At the military facility, the majority are in Camp 6, the grim prison built to hold suspected terrorists after the attacks of September 11, 2001. The few reports that have emerged reveal detainees being badly underfed, held in solitary confinement, hearing others’ screams, and on one day in February, six of them being strapped to restraint chairs to avoid self-harm.

This is part of a larger, historic in size use of the United States’ armed forces against migrants. The administration is sending a reported 9,600 active-duty troops to the border. Including National Guard personnel and Border Patrol agents, there are 4.6 uniformed personnel for every migrant whom Border Patrol apprehended in March. The administration has deployed Stryker combat vehicles, intelligence gathering aircraft and drones, and naval guided-missile destroyers in the oceans next to both coastal borders with Mexico.

The administration plans to use military bases as spaces to detain migrants. Military planes are being used for deportations. The armed forces will be expected to play a major role in the logistics of mass deportation because ICE simply does not have enough personnel.

This, along with a possible future invocation of the Insurrection Act of 1807—which gives the President wide latitude to use the military against what he perceives to be disturbances of public order—could lead to a historic disfigurement of the U.S. military’s minimal, non-political internal role. That, in turn, will set a terrible civil-military relations example for Latin America, a region where most nations only emerged from military dictatorship within the last 40 years.

Looming escalation of the “war on drugs”

On April 3, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) announced the Trump administration’s drug policy priorities. The top priority listed is “Reduce the Number of Overdose Fatalities, with a Focus on Fentanyl.” As context, Trump took office amid the first decline in U.S. drug overdose deaths in four decades: provisional data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a 24 percent drop in such deaths in the 12-month period from October 2023 through September 2024.

The Trump administration has thus inherited the first positive signs in years regarding the country’s horrendous drug overdose crisis, and the government’s own data point to public health-based measures as key to reducing deaths related to illicit fentanyl and other drugs. The CDC attributes the decline to multiple factors, highlighting “widespread, data-driven distribution of naloxone” (an overdose-reversing medication) and “better access to evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders,” among other prevention and response policies.

Despite the welcome news that overdose deaths are falling, the decline is still incipient and the number of Americans dying from drug overdose remains shockingly high, with 87,000 deaths in the 12-month period from October 2023 to September 2024. So achieving further reductions in overdose deaths should be a top drug policy priority, and ONDCP’s declared intention to “expand access to overdose prevention education and life-saving opioid overdose reversal medications like naloxone” is a goal backed by evidence and with increasing support across the country. At the same time, however, the Trump administration is also reported to be proposing massive cuts in health and social safety-net spending, including eliminating a grant program that supports the distribution of naloxone.

Even worse, the bulk of Trump’s rhetoric and actions on illicitly-manufactured fentanyl and other illegal drugs in his first 100 days has focused on escalating the tried-and-failed tactics of a ‘war on drugs’ based on police and military operations seeking to cut off the supply of illicit drugs. Most of Trump’s drug war focus has been on Mexico given the predominance of Mexico-based organizations in manufacturing and smuggling fentanyl into the United States. But the administration has also signalled its readiness to pressure Colombia’s Petro government to crack down on coca cultivation, with a looming threat of “decertification” and sanctions. At the same time, Trump officials appear eager to support Ecuador with infusions of U.S. security aid to bolster President Noboa’s war on drug trafficking and organized crime. In 2024, Noboa declared Ecuador to be in a state of internal armed conflict, unleashing the military to pursue criminal gangs and restricting human rights protections.

In his focus on Mexico, Trump has threatened and partially imposed 25 percent tariffs on Mexican goods as a purported measure to force Mexico to “stop” the entry of illicit drugs (and undocumented migration) at the U.S. southern border. Mexico’s responses to this pressure have included sending additional military troops to its already-militarized side of the border.

The Trump administration is also reportedly weighing the possibility of U.S. military action in Mexico. In February, the State Department designated six Mexican criminal groups as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). While this does not authorize military action, it can be seen as an indicator that such action is under serious consideration. Multiple news reports in April suggested that the Trump administration is discussing carrying out drone strikes against people and facilities in Mexico.

Drone strikes present obvious risks of harm to civilians without offering any reasonable prospect of meaningfully or sustainably reducing drug production in Mexico or drug availability in the United States. Just as decades of an often-militarized drug war in the region have not stemmed the illicit drug supply, much less can U.S. military strikes be expected to bring solutions.

Further, if such strikes were carried out unilaterally, it is hard to overstate the wide-ranging negative impacts they would have on the U.S.-Mexico relationship. Among other outcomes, they would likely undermine any chance of cooperation with Mexico’s government on actions that could sustainably weaken organized crime’s power, such as addressing impunity, corruption, and the flow of U.S. arms to Mexican cartels. As Trump officials consider drone strikes or other forms of U.S. military action in Mexico, it is important to note that Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth is moving to disband Pentagon offices tasked with preventing and responding to civilian harm during U.S. combat operations.

Wreaking havoc on U.S. international assistance

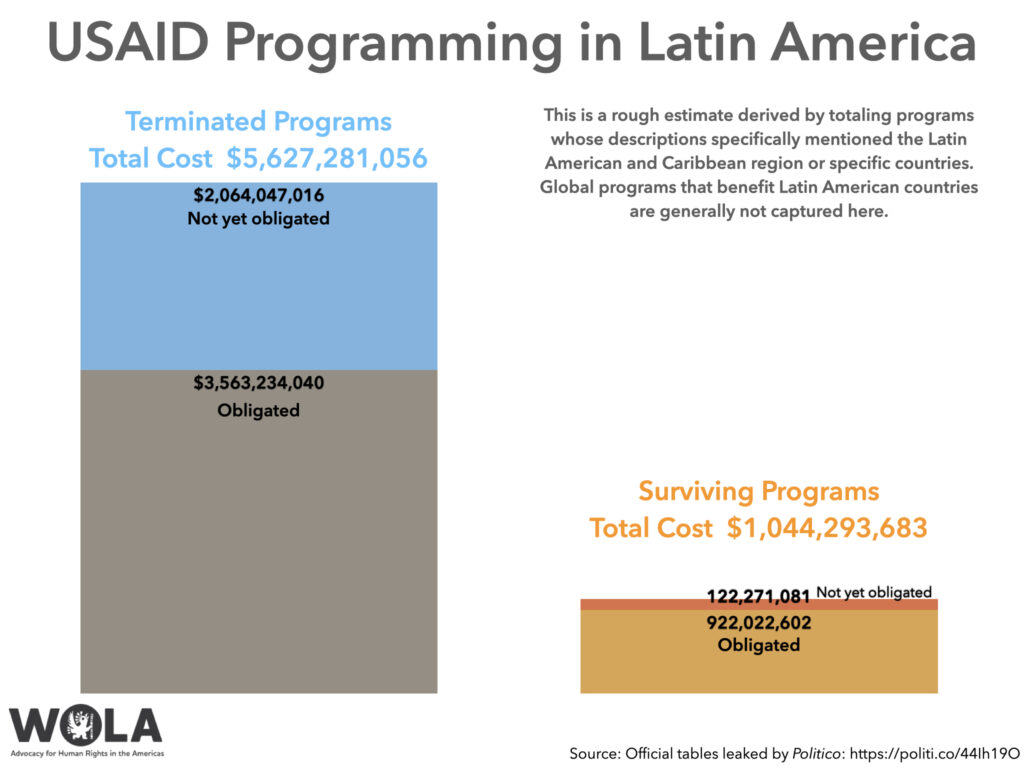

As WOLA indicated in January, even a pause in State Department and USAID-managed foreign assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean—which totaled a little over $2 billion in FY 2023, the most recent year for which an actual amount is available—caused irreparable harm. Already with the freeze, over 70 percent of 115 organizations working on immigration, general human rights, governance/transparency, strengthening civil society, or women’s rights in Latin America that were surveyed by WOLA in late January and early February reported that they would have to cut projects and reduce staff and/or consultants.

The announced 90-day review, reportedly extended another 30 days, has now resulted in the dismantling of the majority of the U.S. foreign aid infrastructure, as well as ongoing confusion about the number of programs and contracts being canceled. A late March document on USAID’s program status, sent to the U.S. Congress and obtained by Politico, revealed that over 85 percent of USAID’s worldwide awards had been terminated, totaling over $27.7 billion. Although some programs appear to have been preserved, the overall impact on humanitarian and global health assistance has been devastating. Only three programs that include the word climate, primarily related to food aid, survived the cuts. All 12 programs addressing gender based violence globally were also eliminated. Moreover, and in a reflection of the administration’s overall priorities, support for democracy and human rights globally through USAID has all but ended. A search of the word democracy in the table provided to Congress suggests that only two democracy programs were preserved globally, both supporting Cuba, while the only surviving program supporting human rights was also for Cuba.

A WOLA analysis that filtered the data for all USAID programs that specifically mentioned Latin America and the Caribbean or specific countries (this leaves out global programs that might have benefited Latin America), identified programs whose multi-year cost totaled $6.67 billion. Of that amount, the Trump administration has eliminated fully 84 percent, leaving a multi-year commitment of just $1.04 billion, of which $122 million remains unobligated.

As per the new restructuring of the State Department, USAID is being incorporated into the Department of State reportedly with 869 staffers—from an agency that once employed over 10,000—mostly to support “lifesaving and strategic aid programming.” And while the biggest cuts and impact on the future implementation of U.S. foreign aid involve USAID (an agency whose funds are specifically allocated in Title II of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act) the cancellation of funding has also impacted other agencies within the State Department.

A WOLA analysis filtered data for all programs managed by non-USAID State Department offices and bureaus that specifically mentioned Latin America and the Caribbean or specific countries (this leaves out global programs that might have benefited Latin America). We identified programs whose multi-year cost totaled $1.96 billion. Of that amount, the Trump administration has eliminated 22 percent, leaving a multi-year commitment of $1.54 billion.

The reduction in funding through the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), where over $543 million in funds had been obligated for the Western Hemisphere in fiscal year 2023 alone, has closed down government regularization programs, reduced UNHCR support for asylum systems, and ended much of the humanitarian and legal assistance provided to refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants by civil society and international organizations in the region. The Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL), which also provides key support to civil society organizations, including human rights defenders at risk, has also seen cuts. Under the proposed restructuring, some of which will require congressional approval, both PRM and DRL would be placed under a new Coordinator for Foreign and Humanitarian Assistance. (They were previously the purview of the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights, slated for elimination.) The “L” will be removed from DRL, now to be named the Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Religious Freedom.

The administration has not deeply cut INL’s government-to-government aid, which is largely equipment and training for uniformed security forces within the old “drug war” framework. On the other hand, it has drastically reduced INL’s grant aid programs that sought to protect populations and weaken organized crime via judicial and citizen security reform initiatives.

The Trump administration has also taken additional steps to dismantle the rest of the foreign aid infrastructure.. It has attempted to gut the Inter-American Foundation, which in recent years received around $52 million in funding from Congress annually, primarily for an innovative model of grassroots development programs, as well as the African Development Foundation and Millennium Challenge Corporation. Other nonprofit institutions created by Congress that also provided grants to civil society organizations to support democracy, human rights, and peace, including in Latin America—the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP)—have been denied access to funds obligated or appropriated by Congress, in the case of former, or been taken over by members of the Department of Government Efficiency, in the case of USIP.

The impacts of the aid cuts throughout the region have been widespread. In Mexico, terminated USAID programs include even projects in areas linked to Trump administration priorities, such as combating crime. These include programs to disrupt youth recruitment by Transnational Criminal Organizations and to improve the effectiveness and accountability of Mexico’s justice institutions. Other terminated activities in Mexico include anti-corruption initiatives, human rights accountability projects (including measures to address Mexico’s disappearance crisis), anti-femicide programs, and work to protect human rights defenders and journalists.

While many of USAID’s programs in Guatemala have been preserved, likely as a result of Rubio’s visit with Guatemalan President Arevalo and USAID Guatemala in February, the chart presented to Congress points to only one remaining project that focuses on addressing impunity in the country. In Honduras, which will hold general elections in November 2025, domestic electoral observation by interdisciplinary groups such as churches and universities has been suspended due to the cuts. This has also affected the electoral institutions themselves, such as the National Electoral Council, which received technical assistance to ensure free and fair elections.

Across Central America, independent media outlets and organizations working on human rights, democracy, government transparency, and anti-corruption efforts have had to cut staff and operations. In an informal survey conducted by WOLA of 21 partner organizations in Central America, over 90 percent had been impacted by the elimination of USAID funding: 70 percent had to cut staff, half reported a serious impact on their budget, and another 25 percent reported a very serious impact on their budget.

In the case of Colombia, an estimated.40 percent of USAID funding went to address the needs of Venezuelan migrants, which has now been reduced to two programs. USAID’s human rights program bolstered Colombian institutions’ ability to prevent and protect against human rights violations, strengthen trade unions and labor rights, provide justice to persons in conflict regions, and implement gender-related policies and services. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights received funds to advance sustainable development through human rights, implement the UN framework on business and human rights, enhance equality and counter discrimination, protect civic space, provide technical support, and strengthen the Colombian institutions’ response to human rights violations. This support was vital to Colombia, where the Institute for Peace and Development (INDEPAZ) reports that from January 2024 up until March 14, 2025, illegal armed groups committed 90 massacres (a total of 343 victims) and killed 211 social leaders.

In his March 4 speech to the U.S. Congress President Trump boasted about ending the $60 million 5-year program for Indigenous and Afro-Colombians (ACIP) as part of DOGE’s efforts to cut U.S. spending. Run by ACDI/VOCA, the project supported the implementation of the Ethnic Chapter of the 2016 peace accord. The funds went to building the Juntanza Étnica to strengthen 113 local ethnic and indigenous organizations to guarantee their communities’ food sovereignty, sustainable development, and peace in the territories. The ACIP programformed 44 public-private partnerships, created the first Business Advisory Board for Ethnic Inclusion, and strengthened the Pacific Business Platform.

According to ACDI/VOCA, through 2024, more than 29,000 ethnic persons benefited from the program, 58 percent of the participants were women, to build their entrepreneurship and leadership, and $35 million were mobilized from private-public and ethnic entities that led to more than 80 projects implemented in 31 municipalities throughout Colombia.

Not even Venezuela, a country where there is bipartisan agreement on the authoritarian nature of its government, as well as concern over the humanitarian and human rights crises, was spared. From FY2017 to FY2024, the U.S. government provided over $3.5 billion in humanitarian aid to Venezuela and countries sheltering Venezuelans. In the same period, democracy, development, and health assistance in Venezuela totaled around $336.2 million. Many programs funded by the U.S., beyond providing humanitarian aid, sought to support efforts for the integration of migrants and refugees to other countries, which was to some extent aimed at preventing their migration to the U.S. The majority of those programs have now been terminated.

The assistance freeze likewise puts at serious risk the situation of civil society and the preservation of civic space as the Venezuelan regime has enacted a law designed to cripple NGOs’ capacity to operate, specifically criminalizing those civic organizations and independent media outlets that receive funding from foreign sources more broadly and U.S. sources specifically. Many Venezuelan organizations receiving U.S. support have not been public about being funding recipients due to security concerns. Stalling funding for democracy programs allocated by Congress ultimately favors Maduro’s efforts to consolidate an authoritarian regime.

Apart from the impact on Venezuelan organizations and media outlets, the cuts to USAID and impact on NED funding have also curtailed the operations of independent press from Cuba and Nicaragua who are primarily operating abroad.

The next 100 days

After these first tumultuous 100 days, in the next few months, Congress will begin debating FY2026 spending priorities and funding levels. The Trump administration has already run roughshod over foreign assistance directives set by law and dismantled institutions established by Congress, including USAID, USIP, and the Inter-American Foundation. While these measures are all being challenged in the courts, the months ahead will put Congress in the spotlight. With Republicans in control of both the House and Senate, it remains to be seen whether and to what extent GOP leaders will assert Congress’s constitutional powers to set funding priorities, even if they go against Trump’s wishes.

Beyond its fundamental constitutional role to determine the federal budget, Congress is the nation’s venue for debating and approving laws to address the country’s needs and demands, such as bills already proposed to provide legal status to various migrant populations in the U.S. In addition, congressional oversight will be essential to request information about the executive’s actions, such as the agreement with the Bukele government in El Salvador to receive migrants without due process. Members of Congress can also continue to oppose unilateral military action against Mexico, speak out for human rights defenders, journalists and other activists at risk, and work to advance peace in Colombia.

Beyond the impacts of reduced U.S. assistance, Latin America will now need to brace for the consequences of the policies the new U.S. administration has already put in motion and for the likelihood of ongoing impulsive decision-making by Trump himself. The region faces the deportation of potentially millions of its citizens from the United States and the corresponding reduction in remittances, as well as economic uncertainties due to U.S. tariffs. Latin America’s leaders will need to navigate these challenges while dealing with a mercurial U.S. president with a transactional style heavy on threats and bullying. Governments led by “friends” of the administration will likely benefit from the relationship and pursue like-minded objectives such as rolling back environmental protections and ending “gender ideology” and support for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Authoritarian governments are also celebrating the United States’ retreat from support for democracy and human rights and stepping up their efforts to quell dissent, while other leaders are promising to investigate recipients of USAID funding.

In this context, we should keep in mind that Latin American civil society is rich with experience defending human rights and working to restore democracy after decades of dictatorships and wars. As U.S. foreign policy lurches into a new era under Trump 2.0, civil society organizations throughout the hemisphere should assess advocacy strategies to adapt to the current moment, examining best practices and lessons learned in the region and globally. Building new relationships and strengthening alliances will be essential to defend past gains and resist the further erosion of democratic norms and the rule of law.