On Friday, May 6, 2022, Guatemalan judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez ordered nine retired military and police officials to trial on charges including the illegal detention, torture, killing and forced disappearance of more than 195 people between 1983 and 1985, during the military regime of Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores.

These crimes are recorded in a military intelligence document that was leaked and made public in 1999, known as the Diaro Militar, or “Death Squad Dossier.” The National Security Archive, the organization that made the document public, called it “a chilling artifact of the techniques of political terror used by Mejía Víctores during that era.”

The military logbook records the abduction, secret detention, and deaths of scores of people. In several cases, it contains a coded reference to their executions. To date, eight of the victims listed in the Military Diary have been located and identified by the Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala (FAFG), thanks to DNA testing and information in the military logbook.

Six were located in a single mass grave during exhumations conducted inside the Comalapa military detachment between 2003 and 2005. Their names and photographs are recorded in the Military Diary, along with the same notation, “29-03-84=300,” indicating the date (March 29, 1984) of their execution (the military used “300” as code to indicate execution). They were identified in 2011 and 2012. FAFG located the other two victims during its exhumation of ossuaries containing thousands of unidentified corpses at La Verbena cemetery, in Guatemala City, in 2011 and identified them in 2015 and 2016.

In addition to the logbook itself, Judge Gálvez had to consider some 8,000 pieces of evidence presented by the plaintiffs, including victim testimony, official military documents, and declassified U.S. government records. Prosecutors also said they would present documents seized from the home of one of the defendants when he was arrested on May 27, 2021.

Families of the victims expressed their satisfaction over the judge’s ruling. “I’m very content to see this day finally arrive,” said Aura Elena Farfán, co-founder of the Association of Families of the Disappeared Persons (FAMDEGUA), a civil party to the case. “Day after day, for 38 years, we have been marching and demanding justice.” She said that she hopes that the court delivers “an exemplary verdict” to dignify the memory of the victims.

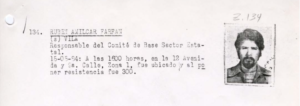

Aura Elena’s brother, Rubén Amílcar Farfán, was captured on May 15, 1984. According to annotation no. 134 in the military logbook, Farfán was killed (denoted by the code “300”) when he put up resistance.

A Fugitive Arrested in Panama

Four days after Judge Gálvez sent the Death Squad Diary ex officials to trial, one of four fugitives in the case, Toribio Acevedo Ramírez, was arrested in the Panama City airport.

His name came up on the final day of pre-trial hearings on May 6, when Judge Gálvez highlighted witness testimony identifying Acevedo Ramírez as participating in torture sessions of political dissidents and of being one of the most vicious members of the “Elite” group created in the 1980s within “The Archive,” a unit of the Presidential General Staff (EMP) that engaged in espionage and counterintelligence in collaboration with Military Intelligence (D-2). The judge exhorted the Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office to investigate him further and to accelerate efforts to capture him.

He was arrested by Panamanian authorities on May 10, as he was de-boarding a plane from El Salvador. According to local news reports, he was on his way to Europe.

Gálvez issued a warrant for the arrest of Acevedo Ramírez one year ago, on May 19, 2021. Eleven officials were captured a week later, on May 27, but he and six others eluded authorities and were later declared fugitives. Shortly after, the Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office issued a red notice with Interpol against Acevedo Ramírez on charges of forced disappearance, homicide, and crimes against humanity.

Three other fugitives are also now in custody; Jacobo Esdras Salán Sánchez turned himself in on June 1, 2021, while Malfred Orlando Pérez Lorenzo was captured in January 2022 in Amatitlán and Alix Leonel Barillas Soto in February 2022 in Guatemala City. Barrillas Soto is accused of the forced disappearance of Rubén Amílcar Farfán.

Rubén Amílcar Farfán, recorded as no. 134 in the Death Squad Dossier, was captured on May 15, 1984 and subsequently killed. He is the brother of Aura Elena Farfán, co-founder of the Association of Families of Disappeared Persons, a civil party to the trial of nine retired military and police officials on charges of illegal detention, torture, killing and forced disappearance of more than 195 people between 1983 and 1985.

The morning after his detention, Acevedo Ramírez was flown to Guatemala. When he appeared in Judge Gálvez’s court on the morning of May 12 for arraignment proceedings he was wearing a mask over his nose and mouth and also over his forehead, presumably to avoid being photographed fully. At the request of Acevedo’s defense lawyers, who said they had no information about the charges against their client and needed time to familiarize themselves with the case, Judge Gálvez suspended the arraignment and rescheduled it for May 18.

Also pending in the case are the evidentiary phase hearings to determine whether other four defendants in the case will also face trial. One of the officials arrested in May 2021, Mavilo Aurelio Castañeda Bethancourt, suffers severe mental impairment and was separated from the case for the time being.

The Diario Militar case will be heard by High Risk Court “A,” which is presided over by Judge Yassmín Barrios. Barrios is known internationally because in 2013 her court convicted former head of state Efraín Ríos Montt of genocide and crimes against humanity against the Maya Ixil population and sentenced him to 80 years in prison. That verdict was vacated just ten days later under intense pressure by economic elites and the military. Ríos Montt died in 2018 before the retrial against him was completed.

Wartime Networks

Guatemalan social media networks lit up in the hours following the breaking news of Acevedo Ramírez’s arrest. Aside from the allegations against him in the Diario Militar case, he has also been implicated in a series of abuses connected to his time working as the chief of security for one of Guatemala’s most powerful companies, Cementos Progreso (CEMPRO), owned by one of Guatemala’s most powerful families, the Novella family. After the company began trending on Twitter, the company circulated a statement on May 12 stating that Acevedo Ramírez had “retired voluntarily” in 2017.

Human rights groups have sharply criticized CEMPRO for failing to abide by legal requirements to consult with local Indigenous communities on proposed investments in their territories, such as the San Gabriel cement factory in San Juan Sacatepéquez, dating back to 2006 and that led to intense conflicts in 2013 and 2014. They also accuse the company of creating private security and intelligence structures to impose the cement factory and related projects, including the usurpation of Indigenous lands that in some instances led to the death of several community members.

Toribio Acevedo Ramírez and his associate and Cementos Progreso manager, Otto Erick Zepeda Chavarría, are reportedly the architects of these illicit structures. According to the Centro de Medios Independientes, Acevedo Ramírez used his military knowledge to monitor, control, and repress individuals and organizations that opposed CEMPRO’s presence in their communities. His case, like that of other senior military officials who were sent to trial last week who have been linked to current illicit networks or structures, illustrates the close relationship between the past and the present in Guatemala.

A case in point is retired general and former Minister of Defense Marco Antonio González Taracena. At the time of his capture in May 2021, he was vice president of the Association of Military Veterans of Guatemala (Avemilgua), created in 1995 by senior military intelligence officers who opposed the peace accords. Avemilgua has long labored to obstruct criminal prosecutions of former military officers accused of serious human rights violations, pressuring legislators to pass amnesty laws, and deploying smear campaigns to intimidate and discredit judges, prosecutors, witnesses and experts linked to these cases.

González Taracena was seen on several occasions accompanying families of the accused in the Ixil Genocide and Molina Theissen cases, as well as negotiating for financial compensation for military veterans and civil defense patrol members with President Jimmy Morales (2016-2020).

Deaths Threats against Judge Gálvez

A short, bookish man, Miguel Ángel Gálvez does not seem like much of a threat to anyone. But as an independent judge, he has taken on some of Guatemala’s most powerful individuals. He sent former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt to trial on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity in 2012. He sent former president Otto Pérez Molina and former vice president Roxana Baldetti to trial on corruption charges in 2015. He has received national and international acclaim because of these and other rulings, but it has also created some enemies.

Demonstrators left a tribute to victims outside of the Palace of Justice in Guatemala City on June 7, 2021 during a hearing for the Diario Militar case, also known as the “Death Squad Dossier.” Photo: Víctor Peña/El Faro

In the past few days, he has spoken to whoever will listen about what he says is a concerted campaign to intimidate him and to obstruct justice in the aftermath of his May 6 ruling. He has received threatening phone calls and text messages. Unmarked vehicles have followed him. Pro-impunity operators have launched an intense smear campaign against him on social media.

One of the most notorious of these operators is Ricardo Méndez Ruiz, president of the Foundation Against Terrorism (FCT). He has posted numerous messages on his social media platforms attacking Gálvez, accusing him of breaching his duties as a judge in the Military Diary case and promising legal action against him.

Méndez Ruiz appeared in Judge Gálvez’s courtroom on May 6 as the judge was issuing his ruling on the Military Diary case. He remained standing for several minutes to make sure the judge noted his presence before taking a seat. One of his close allies, Tilly Bickford, was also in the courtroom. Bickford, who ran unsuccessfully for Congress with the Unionista Party of Álvaro Arzú, played an outsized role in the campaign against former attorney general Thelma Aldana and the Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). At one point she stood up and started moving around the courtroom, snapping pictures of the judge, the civil parties, and families of the victims observing the hearing in the courtroom gallery, flouting the protocol established by the judge for journalists to stay within a cordoned-off part of the courtroom. The judge asked her to show her credentials to prove that she was a journalist, which she did, then ordered her to respect the protocol and maintain silence. The tension in the room was palpable.

On May 10, Méndez Ruiz announced he was filing a lawsuit against Gálvez. The following day he did just that. Other activists have posted a series of threatening messages on social media platforms, including one, Cuban citizen Barbara Hernández, a self-proclaimed anti-communist who has been linked to corrupt Guatemalan oficials, who refers to Gálvez frequently in her posts as a “judicial terrorist.”

Last July, the U.S. State Department included Méndez Ruiz on the Engel List of corrupt and undemocratic actors, who are denied entry into the United States and face other potential sanctions. Mendez Ruiz “attempted to delay or obstruct criminal proceedings against former military officials who had committed acts of violence, harassment, or intimidation against governmental and nongovernmental corruption investigators,” according to the State Department.

Hours after the arrest of Acevedo Ramírez was made public, President Alejandro Giammattei gave a speech attacking independent judges and prosecutors, many of whom have fled Guatemala in the wake of a series of attacks and efforts to criminalize them.

He referred to them sarcastically as the “anti-corruption champions” and the “guardians of justice” and criticized an unnamed “superpower” (a reference to the United States) for its lists sanctioning corrupt officials. He promised to make his own list, which he referred to as the “vulture list,” a veiled reference to a paramilitary group that called itself the “Justice Vultures” and carried out “social cleansing” operations during the Guatemalan civil war.

“We are going to put the enemies of Guatemala on that list,” he said, adding, in reference to the Engel list: “if they put you on those lists it is meaningless; at least the Vulture List will be worthwhile.”

Notably, current Attorney General and close Giammattei ally, Consuelo Porras, was also sanctioned by the U.S. State Department last year, accused of obstructing justice and issuing phony indictments against more than twenty anti-corruption prosecutors and judges. Giammattei is currently deliberating whether to reappoint Porras as Attorney General and risk additional U.S. sanctions.

In this context, international organizations have in the last hours called on Guatemalan authorities to guarantee Judge Gálvez’s security and to ensure that he can continue his work without interference or intimidation.

When asked whether this is a good time to pursue their case, the families in the Military Diary case responded unequivocally. One of them summed it up this way: “There is never a good time to pursue justice in Guatemala. We have come this far, and we are going to continue until we see justice done.”

*This article was originally published in the Salvadoran digital medium El Faro on May 16, 2022 and republished with permission. See the original article here.

Jo-Marie Burt is a Senior Fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and associate professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

Paulo Estrada is a human rights defender. They are co-founders and co-directors of Verdad y Justicia en Guatemala, which monitors and reports on war crimes prosecutions in Guatemala.