Key Findings

Contrary to popular and political rhetoric about a national security crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border, evidence suggests a potential humanitarian—not security—emergency. This report, based on research and a field visit to El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico in April 2016, provides a dose of reality by examining one of the most emblematic of the U.S.-Mexico border’s nine sectors, one that falls within the middle of the rankings on migration, drug seizures, violence, and human rights abuses. At a time when calls for beefing up border infrastructure and implementing costly policies regularly make headlines, our visit to the El Paso sector made clear that what is needed at the border are practical, evidence-based adjustments to border security policy, improved responses to the growing number of Central American migrants and potential refugees, and strengthened collaboration and communication on both sides of the border.

- With 408,870 migrant apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border in fiscal year (FY) 2016, overall undocumented migration is at levels similar to the early 1970s. Apprehensions of migrants per Border Patrol agent are less than one-tenth what they were in the 1990s. With 19 apprehensions per agent, FY2015 had the second-lowest rate of the available data. It makes sense that staffing has leveled off since the 2005-2011 buildup that doubled the size of Border Patrol.

- The number of Mexican migrants has fallen to levels not seen since the early 1970s, and declines have been fairly consistent. Between FY2004 and FY2015 there were fewer apprehensions of Mexican citizens each year than in the previous year. Apprehensions of Mexicans in FY2016 increased by 2.5 percent. Even though the nearest third country is over 800 miles away from the U.S.-Mexico border, Mexicans comprised less than half of migrants apprehended there in FY2014, and again in FY2016.

- Of the migrants arriving at the border, many are children and families from Central America who could qualify as refugees in need of protection. A United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) analysis of credible fear screenings carried out by U.S. asylum officers revealed that in FY2015, 82 percent of women from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, as well as Mexico, who were screened on arrival at the U.S. border “were found to have a significant possibility of establishing eligibility for asylum or protection under the Convention against Torture.”[1] This phenomenon is not a threat to the security of the United States. Nor is it illegal to flee one’s country if one’s life is at risk. Most Central American families and children do not try to evade U.S. authorities when they cross: they seek them out, requesting international protection out of fear to return to their countries.

- Violent crime rates in U.S. border communities remain among the lowest in the nation, and violence has largely decreased on the Mexican side as well. The El Paso crime rate in 2015 was below the U.S. national average. Although homicides have increased in Ciudad Juárez during 2016, the security situation has dramatically improved from when the city was considered the murder capital in the world in 2010.

- Seizures of cannabis, which is mostly smuggled between official ports of entry, are down at the border. However, seizures of methamphetamine and heroin have increased, indicating that more drugs are probably getting across and, in the case of heroin, feeding U.S. demand that has risen to public-health crisis levels. Meth, heroin, and cocaine are very small in volume and are mostly smuggled at official border crossings. Building higher walls in wilderness areas along the border would make no difference in detecting and stopping these drugs from entering the country.

- Ports of entry along the border are understaffed and under-equipped. As evidenced by the El Paso sector’s continued long wait times, ports of entry remain understaffed and under-equipped for dealing with small-volume, high-potency drug shipments, and for dealing more generally with large amounts of travelers and cargo. Much of the delay in hiring results from heightened screening procedures for prospective Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents to guard against corruption and abuse, an important effort in need of additional resources. Screening delays are also the principal reason for a slight recent reduction in Border Patrol staffing.

- Although new Local Repatriation Arrangements (LRAs) between the United States and Mexico are a step forward in protecting Mexican migrants returned at the border, some challenges still remain in their implementation. Both governments announced on February 23, 2016 the finalization of new LRAs to regulate the return of Mexican migrants at nine points of entry along the border. The agreements represent important efforts of both governments to curtail many of the practices that negatively affect this vulnerable population, such as nighttime deportation. In the El Paso sector, however, repatriated migrants are often returned without their belongings, such as cell phones, identification documents, and money, presenting them with challenges in accessing funds, communicating with family, and traveling in the country.

- There are fewer complaints about Border Patrol detention conditions and abuse by agents in the El Paso sector compared to other parts of the border. However, there are concerning reports about abuses by CBP agents at El Paso’s ports of entry. A May 2016 complaint lodged by several border organizations points to troubling incidents of excessive force, verbal abuse, humiliating searches, and intimidation by agents at the ports of entry in El Paso and southern New Mexico that must be investigated and addressed.

- Strong law enforcement and community relations in El Paso have played a key role in making it one of the safest U.S.-Mexico border cities. Consistently ranked one of the country’s safest cities of its size, El Paso demonstrates the importance of communication and constructive relationships between communities and border law enforcement agencies. Local and federal authorities and social service organizations interviewed noted interagency coordination, open lines of communication, and strong working relationships throughout the sector. The local policy of exempting offenders of Class C misdemeanors from federal immigration status checks does much to ensure community members’ willingness to cooperate with law enforcement without fear of deportation. However, reports of racial profiling do exist, and state-level policy proposals against “sanctuary cities,” if passed, could threaten this trust.

- Mexican federal and municipal officials and civil society provide important services for repatriated migrants, and could be a model for other Mexican border cities. Mexico’s National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) works in close coordination with the one-of-its-kind Juárez municipal government’s office to provide important basic services to repatriated migrants and assist them with legal services, recovering belongings left in the United States, and transportation to the interior of the country. Civil society organizations also provide similar important services to migrants and document abuses by U.S. and Mexican officials.

- U.S.-Mexico security cooperation is increasingly focusing on institutional reform issues at the state and federal levels. U.S. agencies provide support for violence reduction efforts in Ciudad Juárez, as well as support for police training and judicial reform for state and federal agents in Chihuahua.

A sign on the Paso del Norte bridge marks the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico

A sign on the Paso del Norte bridge marks the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico

Introduction

WOLA thanks the Ford Foundation for the support that made this research possible.

As researchers who follow events at the U.S.-Mexico border, we are surprised by how this region gets portrayed. Politicians—in Washington, in non-border states, and also in border states’ non-border areas—get remarkable mileage out of calls to address an emergency situation in which uncontrolled migration, drug trafficking, and terrorist infiltration scenarios threaten the American people’s security. WOLA does not see a security crisis at the border. Apprehensions of undocumented migrants at the border continue to be low, resembling apprehension numbers from the early 1970s, violent crime rates are low on the U.S. of the border and have dropped in many Mexican border cities, and the increase in drug seizures (with the exception of cannabis, which is decreasing) is happening at the ports of entry, not in the areas where some propose that more walls be built.

What we do see is a potential humanitarian emergency. The overall migrant population is smaller, but rapidly becoming less Mexican, with fewer males and adults, and increasingly more motivated by fear of violence than by hope of economic opportunity. And hundreds of migrants, who seek to avoid detection, are driven to attempt the journey through treacherous wilderness zones and die painful deaths each year on U.S. soil, particularly in Arizona and south Texas.

To get a sense of the security and humanitarian reality, and to hear about the refinements and adjustments needed to U.S. border security policy, WOLA staff travel often to sectors along the U.S.-Mexico border. (Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border region into nine sectors.)

Since 2014, we have twice reported from the Rio Grande Valley sector, in far southeastern Texas near the Gulf of Mexico, which receives the majority of Central American unaccompanied child and family migrants, receives the largest number of migrants in general, and ranks second in seizures of several types of drugs.[2] This time, we wanted to look at a more “typical” sector, one that falls in the middle of the rankings. A sector that, like most of the rest of the border, has been relatively quiet recently.

Here is an account of an April 2016 visit to the El Paso sector, which comprises the westernmost 88 miles of the Texas-Mexico border and all of the 180-mile New Mexico-Mexico border. It was our first visit there since the fall of 2011.[3]

Overview of the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez Border Region

El Paso (population 680,000) sits across from Ciudad Juárez (population 1.3 million), Mexico’s fifth-largest city. The cities are separated by the Rio Grande, which here, about 700 miles upstream from the Gulf of Mexico, is a trickle, much of its flow drawn off by irrigation canals. Juárez is visible almost anywhere you stand in El Paso.

A view of the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez metropolitan area from an overlook in El Paso

The cities have a close relationship. On the U.S. side, over 80 percent of the population is of Mexican heritage.[4] As a result, attitudes toward migration from Latin America are less strident than what one hears in the interior of the United States or from state officials in Arizona or Texas. El Paso is a Democratic Party bastion, its politics are to the left of this “red” state.

On the Mexican side, Ciudad Juárez has grown extremely quickly, spurred by the maquila (light industrial assembly) sector, which attracted internal migration to the city. This growth outpaced both governance and the formation of a strong social fabric. When it occurred in the late 2000s, the security breakdown, fueled by rivalries between drug-trafficking organizations, was spectacular. In 2010, as the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels fought for control, Ciudad Juárez likely had the highest homicide rate in the world. Businesses closed, and residents with financial resources fled for the U.S. side of the border. That same year, El Paso—which consistently rates among the safest U.S. cities over 500,000 population—suffered only five homicides.[5] As this report notes, Ciudad Juárez has since seen a dramatic improvement in public security.

Longtime residents and law-enforcement officials told WOLA of the 1990s and before, when El Paso’s border was far more porous. Border Patrol apprehended 150,000 or more migrants (and in 1986, 312,000) in the sector each year—except for two—between 1978 and 1993. These were mostly Mexican citizens attempting to migrate through the sector, and a similar number probably made it through into the United States. Drivers had to be alert to the danger of hitting a migrant on Interstate 10, which closely follows the border. Residents of neighborhoods by the river at times suffered petty theft, as migrants passing through their yards even took items hanging on their clotheslines.

Along with San Diego, El Paso saw the first big border security crackdown during President Bill Clinton’s first term. Operation “Hold the Line” in 1993 increased the Border Patrol presence and use of technology to detect border crossers. Later came construction of taller, double fencing along the U.S. bank of the river, in the urban part of the sector. In downtown El Paso, the crackdown worked: undocumented migration declined dramatically. In every year between FY2009 and FY2015, Border Patrol apprehended fewer than 15,000 migrants per year in the entire sector, recording the lowest annual numbers since 1966-67. Success in El Paso, however, led to migration elsewhere over the past 20 years, as apprehensions jumped in other sectors along the U.S.-Mexico border, especially Arizona and more recently southeast Texas.

El Paso shows the value of rational, common-sense improvements to border security, like improving infrastructure in populated areas. The sector also demonstrates the importance of communication and constructive relationships between communities and border law enforcement.

While much appears to be going in the right direction in the El Paso sector, we found some lingering and emerging reasons for concern, which we will discuss further below.

Important Changes in the El Paso Sector

Migrant Apprehensions are Low, But on the Rise

Between 1960 and 1993, El Paso was the second most heavily traveled of the nine Border Patrol sectors: only San Diego saw more apprehensions of migrants. Of all whom Border Patrol apprehended, 20.2 percent were captured in El Paso. In FY1993, Border Patrol apprehended 285,781 migrants in this sector. In FY2015, apprehensions (14,495) were 95 percent fewer, ranking El Paso sixth out of nine sectors and accounting for only 4.4 percent of all migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border.[6] Apprehensions for FY2016 show a proportionally large rise, although still at manageable levels. In FY2016, Border Patrol apprehended 25,633 migrants in this sector, which also saw a 364 percent increase in apprehensions of mostly Central American family unit members (5,664) compared to FY2015 (1,220).[7]

Migration decreased after Border Patrol launched Operation Hold the Line in 1993, which made border crossing more difficult in the densely populated part of the sector, where the urban zones of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez meet. With just one border metropolitan area and rugged, sparsely populated desert elsewhere, and with a great distance between El Paso and other U.S. cities that might be destinations for migrants, the sector proved relatively easy to control.

Hold the Line was followed by a similar crackdown in San Diego, which saw a similar drop in border crossers. Migrants shifted to more inaccessible—and dangerous—desert areas, and by 1998, Arizona’s Tucson sector had surpassed both El Paso and San Diego as the leading region for apprehensions. Tucson held this position until being eclipsed in FY2013 by the Rio Grande Valley sector in far southeast Texas, along the Gulf of Mexico, which today is the main destination for Central American migrants.

The “apprehensions” statistic, of course, only tells us how many migrants were caught. This is useful for discerning migration trends by sector over time. But there is no way to measure the number of migrants who evade Border Patrol. The agency tries to estimate what it calls “got-aways” based on imagery, footprints, and other clues, though it does not actively publicize this data. According to a recently released internal Department of Homeland Security (DHS) report, in FY2015 Border Patrol caught just 54 percent of undocumented migrants entering the United States. About 170,000 eluded capture; the report estimates that 210,000 migrants eluded capture in FY2014.[8]

As at the rest of the border, migrants apprehended in the El Paso sector are increasingly Central American. While not the main destination, El Paso is now seeing some of the strongest growth in arrivals from Central America, as discussed below. In the 16 fiscal years between 2000 and 2015, only 3.9 percent of apprehended migrants in El Paso were what Border Patrol calls “Other Than Mexican” (OTMs), nearly all of them from the “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.[9] This put El Paso in fifth place among all sectors over these 16 years. (In fact, during the 2000-2015 period the nine sectors rank exactly according to their distance from Central America, with the Rio Grande Valley, where Texas dips south, closest to Mexico’s southern neighbors, in first place with 43.0 percent of apprehended OTMs.) In FY2015, the last year for which we have full data, 26.3 percent of migrants apprehended in El Paso were “Other Than Mexican”—a huge increase over the trend from 2000 to 2015.

Beyond Central Americans, the El Paso sector sees very few “Other than Mexican” migrants from outside the Americas. While we do not have statistics, DHS authorities told WOLA that the sector had seen no increase in apprehensions of so-called “Special Interest Aliens,” defined in a 2004 Border Patrol memo as migrants from countries—most from outside the hemisphere—“that could export individuals that could bring harm to our country in the way of terrorism.”[10]

Few Central American Families, Until Recently

Our visit to El Paso made clear the wide variety of approaches U.S. enforcement agencies have adopted to address the increase in Central American migration, and what has and has not changed at the border since the significant uptick in migration flows in 2014 that caught U.S. officials largely off guard. Although the numbers of Central Americans apprehended are higher in 2016 than in 2015, the situation on the ground is now more orderly, with a level of preparedness for the possibility of handling even larger migrant numbers that was not present two years ago.[11]

At the height of the summer 2014 “crisis,” Customs and Border Protection (CBP, the DHS agency that incorporates Border Patrol and the Office of Field Operations (OFO) agents who staff the ports of entry) began to fly Central Americans apprehended in the Rio Grande Valley to El Paso and Laredo in Texas and San Diego, California, so these Border Patrol sectors could assist in processing.[12] Border Patrol personnel in El Paso processed these new arrivals, as well as migrants crossing through the El Paso sector. With the exception of Mexicans not seeking asylum, the majority of single adult males from Central America, and unaccompanied children, these migrants—predominantly family units and women with children—were then taken by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to local service providers, primarily Annunciation House, a Catholic shelter that has provided hospitality to migrants and refugees for nearly 40 years.[13] Because the House can only accommodate 60 people, staff and volunteers have worked to find other housing alternatives, including local churches. In an opportune set of circumstances, the Nazareth Living Care Center, run by the Catholic Church, had finished a new wing that was not yet being used as a nursing home. Nazareth Hall was opened in the summer of 2014 to temporarily house Central American and other migrants and potential refugees, and has remained open to this day.

Nazareth Hall was not at capacity when WOLA staff visited in April, but volunteers were preparing for an increase in arrivals, as was Annunciation House.[14] This preparation was in response to the growing number of apprehensions of family units from Central America in the sector, a 364 percent increase for FY2016 compared to FY2015, as well as a significant number of Cubans who have arrived in El Paso after traveling from as far away as Ecuador.[15] Over 4,810 Cubans arrived in El Paso between October 2015 and July 2016, many needing temporary shelter while they decide where and how to make a life in the United States.[16] Unlike migrants from other countries, Cubans are automatically granted legal status in the United States once they arrive at a U.S. land border.

Border Patrol, Other Law Enforcement, and Community Relations are Relatively Positive

An estimated 59,000 people in El Paso County are undocumented, about 8 percent of the population.[17] Of those, 57 percent have lived in the city for 10 years or more.[18] Local law enforcement agencies, which rely on community support, trust, and cooperation to carry out their work, have emphasized that immigration enforcement is a federal, not local, responsibility. In 2011 testimony before the House Homeland Security Committee’s Subcommittee on Border and Maritime Security, El Paso County Sheriff Richard Wiles said that to “have local and county law enforcement officers engage in federal immigration enforcement… is bad policy,” most importantly because it would “undermine the trust and cooperation of immigrant communities,” potentially leading people to choose not to report crime or cooperate with authorities for fear of having to prove their citizenship.[19]

According to interviews with law enforcement officials, the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office does not ask for social security numbers of those with whom it interacts; similarly, the City of El Paso Police Department does not share fingerprint data with ICE for Class C misdemeanors, the lowest level criminal offense. Both agencies have implemented a community policing model that includes bilingual presentations and direct community involvement.

As an urban border zone, El Paso hosts many federal, state, county, and local law enforcement agencies, as outlined in WOLA’s 2011 report.[20] Relations between these agencies—at both the federal and local level—and the greater El Paso community are relatively positive and officials at all levels cite collaboration between Border Patrol, ICE, and other law enforcement agencies as one of the sector’s strengths. “While issues do arise from time to time, I would say the working relationship between federal, state, county and local law enforcement agencies in El Paso is outstanding and unmatched in other jurisdictions,” testified Sheriff Wiles in the same 2011 hearing.[21] Five years later, this statement appears to hold true. Border Patrol hosts regular, interagency intelligence meetings at patrol stations, and the U.S. Army base at Fort Bliss hosts a monthly breakfast to bring together the numerous enforcement agencies in the area. According to one local law enforcement official, this collaboration is a primary reason why El Paso is ranked among the safest cities in the country.[22]

Better communication in recent years has improved Border Patrol-community relations. Border Patrol now employs a non-uniformed community liaison in El Paso, and, according to reports, “regularly invites community members to participate in various CBP events and to speak with Border Patrol agents.”[23] In 2013, the Border Network for Human Rights’ (BNHR) Abuse Documentation Campaign Preliminary Report found “not a single verifiable report” of abuse involving either Border Patrol or the El Paso Sheriff’s Department, though it documented concerns about the sheriff’s officers in Doña Ana County, New Mexico asking about legal status, wrongful ICE deportations and detentions, and multiple complaints of abuse at ports of entry.[24]

Local social service organizations also reported constructive relationships with ICE and Border Patrol, especially in recent years. Annunciation House began receiving requests to take in migrants released from federal custody as far back as 2009, in addition to receiving a number of migrants flown in from other, busier sectors such as the Rio Grande Valley more recently. When WOLA visited, Nazareth Hall staff had just received a call that 50 people would be arriving from ICE custody that day, tripling the shelter’s occupancy. A former staff member noted that, in addition to working closely with ICE, Annunciation House also receives migrants from Border Patrol custody.[25]

Looking into El Paso, just north of the Rio Grande, with an irrigation canal in the foreground

Fewer Complaints about Border Patrol Detention Conditions

Under border-wide CBP guidelines set in October 2015, apprehended migrants can be held in short-term holding cells for up to 72 hours, a six-fold increase from the previous standard of no more than 12 hours.[26] Unlike elsewhere along the border, criticisms of short-term Border Patrol detention facilities in El Paso do not include assault or rough treatment while in custody, yet local activists noted concerns regarding tight handcuffs and occasional verbal abuse from agents. Throughout the border, reports of extremely cold temperatures in Border Patrol holding cells have caused these facilities to be known as “hieleras” (“iceboxes”) by those held inside; in addition to extreme air conditioning, WOLA also heard reports of poor quality of food and water in short-term detention facilities in the El Paso sector.

Other areas of the border have broader complaints. In Tucson, immigrants-rights groups filed a class action lawsuit in June 2015 citing harsh conditions including overcrowding, unsanitary holding cells, cold temperatures, and lack of adequate food, water, and hygiene items in all CBP short-term detention facilities.[27] In the Rio Grande Valley, a December 2015 report by the American Immigration Council noted: “In addition to the fact that there are no beds in the holding cells, these facilities are extremely cold, frequently overcrowded, and routinely lacking in adequate food, water, and medical care.” The report also included firsthand accounts from migrant families citing harassment, ridicule, and the separation of mothers and children held in short-term Border Patrol facilities.[28]

Improved Deportation Practices

In a significant step forward, new Local Repatriation Arrangements (LRAs) signed by the United States and Mexico in February 2016 have put an end to the practice of nighttime deportations in all Border Patrol sectors. In the past, Mexican nationals could be deported to dangerous border cities in the middle of the night—increasing their risk of being kidnapped, robbed, or victims of other crime. Under the new local arrangement for the sector, deportations from El Paso can only take place between 5:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. for adults, and 8:00 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. for unaccompanied children, pregnant women, or other more vulnerable groups.[29] While the LRAs’ language allows for exceptions to limits on night deportations for “assisting a vulnerable person, law enforcement need, or operational tempo,” groups on both sides of the border agreed the new guidelines are generally being followed. According to the Municipal Office for Attention to Migrants (Oficina Municipal de Atención a Migrantes) in Juárez, returned migrants are primarily received from 6:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., the majority of whom then head to the city’s migrant shelter.[30]

The Border Security Buildup Has Cooled

The El Paso sector is following a border-wide trend in Border Patrol staffing. After a dizzyingly rapid buildup—the force roughly doubled in size between 2005 and 2011—the Border Patrol’s personnel strength has leveled off, and even begun to decline somewhat. In El Paso, the decline is more pronounced than nationwide.

After a 2011 peak of 21,444 agents nationwide, Border Patrol’s personnel strength was 20,081 (5 percent less) in January 2016.[31] The number of these agents assigned to the U.S.-Mexico border rose to 18,611 in 2013, but dropped to 17,522 (6 percent less) by 2015.

El Paso is one of four U.S.-Mexico border sectors that saw a double-digit percentage drop in Border Patrol staffing between FY2013 and FY2015. This is not surprising: a look at migrant apprehension data makes clear why newly hired agents are not being assigned to El Paso. In all of FY2015, the sector measured six apprehensions per Border Patrol agent for the year, ranking last of all nine U.S.-Mexico border sectors. El Paso’s “apprehensions per agent” ratio has dropped by 93.5 percent (from 92 apprehensions per agent) over the past 10 years.

The border’s busiest sector, Rio Grande Valley, measured 48 apprehensions per agent in FY2015, and 84 in FY2014. For a while in 2014 and 2015, agents in the El Paso sector, connected via internet video feed, spent hundreds of person-hours processing migrants apprehended in Rio Grande Valley. That sector also concentrates a recent buildup of Texas state law-enforcement agents, and a few Texas National Guard personnel carrying out surveillance and reconnaissance missions. These agencies are far less active in El Paso.

The Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act for 2016 requires Border Patrol to field 21,370 full time-equivalent agents, more than 1,000 greater than the force’s present actual size. (The Department’s FY2017 proposal is for 300 fewer, or 21,070.) Border Patrol agents have told WOLA, however, that recent reductions in overtime hours—the result of a 2014 law that purported to “provide stability to agent pay”—could be encouraging some agents to retire or quit.[32] Uncertainties surrounding pay and compensation, coupled with less-than desirable duty locations, have driven BPA [Border Patrol agent] attrition to a point where losses were significantly outpacing gains,” CBP officials testified in April 2016.[33]

Nationwide, Border Patrol is facing a 5.5 percent per year attrition rate—more than 1 in 20 agents leave the force each year—which means it needs to hire more than 1,000 new agents per year just to avoid further reductions.[34] Filling the gap has been more difficult due to improved CBP standards for hiring new officers. The CBP officials’ April testimony notes, “Individuals must successfully complete an entrance exam, qualifications review, interview, medical exam, drug screening, physical fitness test, polygraph examination, and a background investigation. The hiring process is challenging for most applicants and a large number do not meet the Agency’s employment requirements.”[35]

In particular, both the CBP testimony and WOLA conversations with Border Patrol agents cite the polygraph examination as an impediment to hiring more personnel. The 2010 Anti-Border Corruption Act made this “lie detector” test a requirement for all applicants for law enforcement positions within Customs and Border Protection as a way to more effectively screen candidates, particularly out of concerns of infiltration into the agency of individuals with connections to drug cartels.[36] But as CBP testified, these tests get delayed because “the number of federally certified polygraph examiners is limited, leading to competition among all agencies to fully staff polygraph programs.” Border Patrol personnel told WOLA, but we have been unable to verify, that only 13 percent of would-be applicants are passing their polygraph examinations as currently administered. (“We have heard failure rates for Border Patrol hires of 70% to 80% and possibly higher failure rates among applicants that reside on the southwest border as compared to the rest of the country,” notes a post to the website of the Border Patrol union local in Tucson, Arizona.[37]) In light of these problems, it has been reported that in 2015 CBP attempted to change the test, but was rejected by government oversight bodies for not meeting the standards for law enforcement screenings.[38]

Improved Border Infrastructure

Just as it saw increases in staffing during the Operation Hold the Line and 2006-2011 border buildup periods, the El Paso sector received generous funding for new border infrastructure. The Secure Fence Act of 2006 authorized the building of a high barrier along the U.S. side of the Rio Grande between the urban zones of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, and between a few miles of the line between New Mexico and Mexico. In most areas, this barrier replaced a low chain-link fence. The new fence closes off about 110 of the sector’s 268 border miles; 13 miles of it is double-layered.[39]

Border fencing outside the city of El Paso

As we heard during our 2011 visit, El Paso residents generally expressed approval of the fencing that was built in densely populated areas. In the past, uncontrolled border crossers posed traffic hazards on commuter highways, and committed numerous “nuisance crimes” like trespassing and petty theft. Between the two large cities, where Border Patrol and other law enforcement can quickly arrive on the scene should someone attempt to cross, the fence has deterred would-be crossers.

In the countryside and desert that make up most of the sector’s border miles, the fence is less useful. Border Patrol agents, who support the idea of fencing, also point out that the fence doesn’t stop would-be border-crossers, it just slows them down. In rural west Texas, the Rio Grande (and the fast-flowing irrigation canals that parallel it) would slow a migrant’s progress for about as long as it would take to scale a tall fence.

We traveled to the town of Fort Hancock, in the eastern zone of the El Paso sector, to see where the fence—after several starts and stops—finally comes to an end. It is a treeless, flat zone of dry, sandy soil, with irrigation canals cutting through it. Interstate 10 runs as close as one mile from the border. Local ranchers have told media that they feel unsafe without fencing, as border-crossers—many of them at night, and many of them, the ranchers believe, carrying drugs—pass frequently through their property.[40]

In these very remote areas, though, the usefulness of fencing appears to be marginal, which is why about 1,300 of the U.S.-Mexico border’s approximately 1,970 miles remain unfenced. Because of the distances involved and the lack of nearby roads, Border Patrol and other law enforcement cannot arrive quickly on the scene when they detect a crossing, the way they can in an urban area. In an urban area, the five to ten minutes that a border-crosser must spend scaling a fence can make the difference between an apprehension and an evasion. In a rural area, it merely reduces the border-crosser’s significant head start.

The border wall ends outside Fort Hancock, Texas

Similarly, damage to the fence may take days to repair if it is in a far-off, rural area. “If you were to put a fence over there and it is not complemented by access roads, by lights, that fence would be gone very fast because nobody would be monitoring it on a regular basis,” then-Border Patrol Tucson (now Rio Grande Valley) Sector Chief Manuel Padilla told the Arizona Daily Star in 2015.[41]

The Secure Fence Act provided surveillance technology to the El Paso sector, principally cameras, mostly mounted on towers (Integrated Fixed Tower (IFT) systems and Remote Video Surveillance Systems (RVSS)), and sensors (Unattended Ground Sensors (UGS) and Imaging Sensors (IS)) to detect border crossings. In Deming, New Mexico, the sector employs one of eight Tethered Aerostat Radar Systems (TARS), a radar-equipped blimp that can detect low-flying aircraft and some suspicious ground traffic.[42] None of CBP’s six Predator-B surveillance drones flying along the border are stationed in the sector, but they do overfly it constantly.[43]

“About 56 percent of the border is deployed in a way that agents and/or our technology can see our activity in real time,” then U.S. Border Patrol Acting Chief Ronald Vitiello testified in March 2016.[44] We do not know the specific percentage for the El Paso sector, although it is unlikely to differ greatly from that national estimate.

Sparsely populated country about 40 miles east of El Paso

Border Patrol agents gave WOLA a brief demonstration of some of the imagery that the agency’s fixed cameras pick up along the border between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. Footage of a recent nighttime attempt to introduce marijuana through drainage tunnels showed the cameras trained along the borderline to be quite capable of picking up movements and giving agents and dispatchers awareness of what was happening. However, we could not help noticing—and Border Patrol acknowledged—that the images’ resolution, which was probably quite impressive when the cameras were purchased, is lower than that obtained by today’s cheaper “point and shoot” camera models. In a May 2016 congressional testimony, then-Acting Chief Ronald Vitiello affirmed that the Border Patrol will continue to use the Capability Gap Analysis Process (CGAP) “to conduct mission analysis and identify capability gaps.”[45] From our observations it would seem that this assessment is still in process is the El Paso sector.

Relatively Few Migrants Perish

A devastating side effect of the past 20 years’ border security buildup has been a rise in the number of migrants who die of dehydration, exposure, or by drowning in U.S. territory. Border Patrol reports recovering the remains of 6,571 people in the 18 years between FY1998 and FY2015.

The presence of fencing, agents, and other counter-measures caused a growing portion of would-be migrants to attempt the journey through treacherous wilderness areas, far from population centers. In environments like the Arizona deserts of the Tucson sector, or the south Texas scrubland where migrants attempt to evade Border Patrol interior checkpoints on foot, authorities and ranchers find hundreds of bodies each year, citizen advocates seek to install water stations and support search and rescue efforts, and Border Patrol—to a varying degree across sectors—installs and maintains rescue beacons for distress calls.

The majority of migrant remains—two-thirds in FY2015, and 57 percent from FY1998-2015—are recovered in the Tucson and Rio Grande Valley sectors. El Paso, with 225 bodies recovered during those 18 years, ranks eighth out of the nine sectors, and ninth in the four years since 2012, when it accounted for only 5 of the 1,464 remains found border-wide.

While receiving less attention, the Laredo sector is probably the most dangerous for migrants to enter; in FY2015, it was the only one in which Border Patrol recovered more than one body for every 1,000 living migrants it apprehended. By this crude measure of risk, El Paso was about one-tenth as treacherous for migrants in FY2015, with 1.4 remains recovered for every 10,000 apprehensions. This was the lowest ratio of all nine sectors last year.

The El Paso sector suffers fewer fatalities in part because the terrain is easier to navigate: it is not as dry as the Arizona desert, and unlike the paper-flat Rio Grande Valley, mountains in the distance serve to orient foot-travelers and keep them from wandering in circles. Most migrant deaths that do occur are drownings in the deceptively fast-flowing irrigation canals that circulate through farmland near the Rio Grande. To date, few remains have been found in the arid New Mexico deserts west of El Paso. The New Mexico-Mexico border area, which is very far from population centers, is not frequented by migrants, though we heard reports that drug smuggling occurs often.

A sign on fencing surrounding an irrigation canal warns in English and Spanish: “Dangerous currents, do not enter”

Thankfully, the overall border-wide trend in migrant deaths is down after an alarming spike in 2012-2013. This is likely due in part to a continued drop in the total number of migrants who seek to evade capture—that is, those who are not Central American children and families actively turning themselves in. It is also an outcome of increased Border Patrol search-and-rescue efforts, including the establishment of Mobile Response Teams, increased deployment of rescue beacons, and additional civil society efforts to maintain water stations and collaborate with search-and-rescue-efforts. In spite of these efforts, migrants continue to perish, particularly in the deserts south and west of Tucson, Arizona, and in Brooks County, Texas, north of the border in the Rio Grande Valley sector.

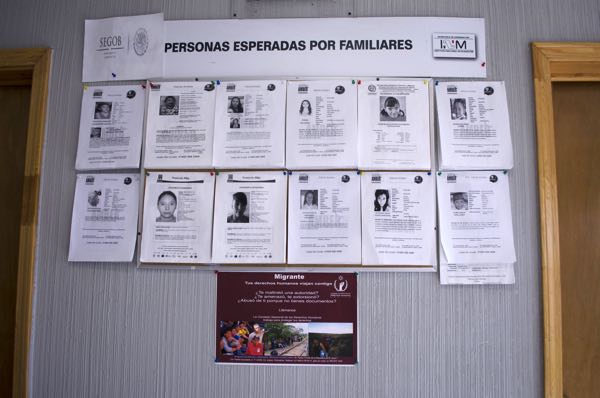

Posters of missing migrants at the INM Humane Repatriation Program office

Posters of missing migrants at the INM Humane Repatriation Program office

Violent Crime Is Down on Both Sides of the Border

It is common to hear U.S. political leaders and pundits refer to towns on the U.S. side of the border as plagued by violent crime and “spillover violence” from Mexican organized crime. One example among many was a 2011 report by two retired U.S. Army generals, commissioned by the Texas Department of Agriculture, which concluded, “Conditions within these border communities along both sides of the Texas-Mexico border are tantamount to living in a war zone in which civil authorities, law enforcement agencies as well as citizens are under attack around the clock.”[46]

The evidence does not back this up: statistics show most of the U.S. side of the border to be safer than the national average, while conditions have improved significantly on Mexico’s side. The El Paso sector is no exception.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) annual Crime in the United States report lists violence statistics from more than 9,000 reporting municipalities. The most recent full-year report, covering 2015, includes data from 290 cities with a population over 100,000. Twenty-three of these cities are within approximately one hundred miles of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Of these 23 border-zone cities, none were in the top 80 for 2015 violent crime rates, and none were in the top 120 for homicide rates.[47] All but five had violent crime rates below the U.S. national rate, and all but three were below the national homicide rate. The most violent border-zone city was Tucson, Arizona, with a 2015 rate of 655.5 violent crimes per 100,000 people. The country’s most violent city in 2015, St. Louis, suffered a rate three times as high (1,817.1), and 12 cities were twice as high. Tucson’s homicide rate was one tenth that of the highest U.S. city in 2015 (St. Louis, 49.9), and 58 cities were twice as high.

The two cities in the El Paso sector, El Paso, Texas and Las Cruces, New Mexico, were sixth and fifteenth, respectively, in violent crime rates among all border cities in 2015. They ranked 11th and 8th, respectively, in homicide rates. In all cases, these two cities were below the U.S. national averages. Seventeen people were murdered in El Paso in 2014, and three in Las Cruces.

Bucking a national trend, both cities in the El Paso sector saw decreases in homicide and violent crime from 2014 to 2015. El Paso County Sheriff’s Office officials told WOLA that few of the crimes they record are perpetrated by undocumented immigrants. Organized crime and gang activity is minimal, the officials told us, characterizing most illegal activity in the county as “crimes of opportunity”: offenses like robberies, fights, or crimes of passion that are more spontaneous than planned, and for which the perpetrator and victim are often known to each other.

The statistics do not cover the El Paso sector’s rural areas, though law enforcement in El Paso assured us that violent crimes are rare. However, ranchers say they feel menaced, especially in the portion of the sector east of El Paso, across the river from the violent Juárez Valley region of Mexico’s Chihuahua state. Here, where fencing has gaps or doesn’t exist, residents worry that many of those now crossing through their territory are not migrants, but drug couriers linked to organized crime, and thus potentially armed. Border Patrol acknowledges the challenge, but contends that security measures inland from the border, like checkpoints and regular patrols, capture or deter most people who cross the border in rural zones.

Across the Rio Grande in Ciudad Juárez and the Juárez Valley, organized crime competition and gang activity continue to be daily challenges, but the situation has improved from the mass bloodshed that likely made Juárez the world’s most violent city in 2010, when estimates of murders ranged from 2,738 to 3,766, of a population of about 1.3 million.[48] (In that year, five people were murdered in El Paso.)

Violent crime rates in Ciudad Juárez have fallen dramatically since then: last year, the city’s homicide rate (19 per 100,000 residents) was similar to that of Miami, Florida, with only 256 homicides. (As discussed below, though, a 20.5 percent increase in homicides reported during the first half of 2016 is troubling.[49]) The progress owes to notable improvements in policing and justice, to increased investment in neighborhood-level violence prevention efforts, and to a likely pact or truce between the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels, whose battle for the region’s trafficking routes underlay much of the earlier spike in violence.

Organized crime remains powerful in Ciudad Juárez, in the farmlands of the Juárez Valley, and in other parts of the state, such as along the drug trafficking routes that run through the virtually ungoverned Sierra de Tarahumara mountain range to the south. However, for the moment at least, the eastern part of the U.S.-Mexico border, particularly the state of Tamaulipas, is considered far more violent.

In that area—across from Border Patrol’s busy Rio Grande Valley sector—U.S. officials and Mexican migrant advocates told WOLA that it is virtually impossible for migrants and their smugglers to cross the border without permission (obtained through payment) from the groups that control criminality there, usually elements of the Gulf and Zetas cartels. Control of border crossings is less rigid in Chihuahua, where individuals or small groups of migrants can attempt to cross into the United States with less chance of being stopped by organized crime. Smugglers bringing larger groups across, though, would likely need a “green light.”

The Rio Grande Valley and Tucson sectors have reported some kidnappings of migrants in recent years, and authorities have documented and raided “stash houses” where smugglers hold migrants, often in crowded and miserable conditions, for extended periods of time. These phenomena are rare in the El Paso sector, though ICE investigators shared concerns that they may be seeing initial signs of increased use of stash houses. Officials also cited long-standing cases of U.S. family or clan groups involved in human trafficking or migrant smuggling, principally in rural New Mexico (the village of Hatch, northwest of Las Cruces, was mentioned twice in interviews).

The problem of so-called “niños de circuito”—juveniles whom drug traffickers and human smugglers employ as couriers and guides, and who may cross back and forth repeatedly—is not as pronounced as in other U.S. border sectors.[50] An analysis of FY2014 data showed that more than one third of the unaccompanied Mexican children apprehended at the border were from the border states of Tamaulipas and Sonora, suggesting that these are areas where recruitment of minors for smuggling is more prevalent (the states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, Guanajuato, and Michoacán accounted for another third of the apprehensions).[51] The same study showed that only 24 percent of the minors reported that it was their first apprehension by U.S. authorities. When asked about the recruitment of minors, Border Patrol officials told WOLA that “it happens” in El Paso, and statistics from a shelter for unaccompanied Mexican migrant children in Ciudad Juárez suggests that it remains an issue in the area. The shelter “Mexico, Mi Hogar,” which is supported by Mexico´s Child Protection Agency (Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, DIF) received 176 circuit children in 2015 and 108 in the first half of 2016. The shelter has focused on an integral intervention approach with these children, however, many challenges remain to provide alternatives to prevent them from becoming voluntarily involved with or forcibly recruited into smuggling rings.[52]

On the U.S. side of the border, CBP has officially ended the Juvenile Referral Process, which screened circuit children to detect human trafficking victims as well as those who could be eligible for detention and possible criminal prosecution in the U.S. given their involvement in smuggling.[53] However, concerns remain about CBP’s interviews of these children and possible referrals to local law enforcement for prosecution, which has happened in Cochise County in Arizona.[54]

Some Noteworthy Efforts on the Mexican Side

Changes in Ciudad Juárez

WOLA’s April 2016 trip to Juárez was in stark contrast to a 2011 visit. While the recent rise in violence in the city is worrisome, the overall security situation has dramatically improved since the 2010 peak. There is no sole explanation for this improvement. The Mexican government credits its own interventions, including the Todos Somos Juárez program of investments in local services and violence prevention initiatives, and increased efforts to reform and professionalize the municipal police force. While these undoubtedly have had an impact, others point to the decrease in violence after Federal Police and the Mexican military withdrew from the city, as well as an agreement or tacit arrangement that was likely reached between the Juárez and Sinaloa cartels.[55]

Another factor is an unprecedented mobilization of civil society behind efforts to address violence in new ways. Several civic organizations created in the early 2000s became more active, while others were created, such as Juarenses por la Paz (Juarenses for Peace), formed by businesspeople, lawyers, and other professionals. In response to outrage and protests by citizens of Juárez and throughout Mexico regarding the January 2010 massacre of 16 young people at a party by a group of armed assailants, the federal government announced a more holistic approach to the security crisis in the city. Termed “Todos Somos Juárez: Reconstruyamos la Ciudad” (“We are All Juárez: Let’s Rebuild the City”), the program committed all levels of the government to spend US$270 million on 160 concrete actions in the city. These included many long-overdue projects such as building new high schools, finishing construction on a hospital, numerous parks and green spaces, temporary job programs, and afterschool programs for students.

One initiative that arose from Todos Somos Juárez was the establishment of the Mesa de Seguridad (Security Working Group). As Lucy Conger outlined in a 2014 Wilson Center study of civil society participation in Juárez, the Mesa:

[i]ncluded officials from all three levels of government, representatives of the security forces including the army, federal, and municipal police and the attorney general’s office together with 24 citizen delegates drawn from the bar association, human rights commission, assembly plant associations, and civic groups including the CMC [medical committee], Juarenses por la Paz, a youth group, a citizen observatory, the strategic plan project, and the university.[56]

Ten commissions within the Mesa address aspects of security and criminal investigations, including the development of monthly crime indicators that are still in use today.[57]

While a full analysis of civil society’s role in addressing the violence in Juárez is beyond this report’s scope, it is clear that this engagement contributed to the reduction in violence and established a working relationship between society and the government that had not existed previously.

Police and judicial reform also played a role. While Chihuahua was the first state in Mexico to transition to an accusatorial judicial system, state and local authorities also placed significant emphasis on police reform. Between 2011 and 2013, Ciudad Juárez’s municipal police chief was Julian Leyzaola, a retired Army general who had previously overseen a period of security improvements as police chief in Tijuana. Leyzaola’s tactics were controversial in both cities.[58] He stands accused of allowing or even supervising torture of alleged corrupt police agents, and some civilians, in Tijuana. In August 2013, the legal affairs office of the Tijuana government concluded that Leyzaola had committed human rights violations and banned him from holding political office in the state of Baja California for eight years.[59] As police chief in Juárez, Leyzaola purged the police force—more than half of the agents within the force were either fired or resigned—and he is credited with helping to ensure that municipal police were better trained and organized. However, state human rights officials affirmed that complaints of abuses by the police, including theft, beatings, and torture, increased under Leyzaola’s leadership.[60] Leyzaola also clearly had enemies: in May 2015 he was shot while driving his car in Juárez, and is now paralyzed from the waist down.

After Leyzaola’s departure in 2013, municipal police reforms have continued. Municipal officials and U.S. diplomats told WOLA staff that more emphasis has been placed on police recruitment, improving background checks, increased training, internal affairs, and place-based crime response strategies.

U.S. Support for Security in Ciudad Juárez

During our visit, WOLA staff met with representatives of the U.S. Consulate General in Ciudad Juárez, who have once again brought their families to live with them in the city after years when officials would leave their families in El Paso. U.S. engagement in Ciudad Juárez has been significant. The city is one of the three geographic areas in Mexico where the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has prioritized Mérida Initiative-funded violence prevention programs. USAID has also supported judicial reform efforts in Chihuahua since 2004.[61]

The State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) also assists judicial reform in Chihuahua, particularly for federal prosecutors and judges. Likewise, INL funds state and municipal police professionalization, particularly through the Chihuahua Police Academy (Escuela Estatal de Policia). INL’s National Police Training Program has trained approximately 1,900 Chihuahua State Police officers in areas such as tactical operations, homicide investigations, dealing with petty drug trafficking, and first line supervision. INL also supports state prosecutors in the use of canine units (with much training occurring in Colombia), and a “train the trainer” program for the state police on their role as first responders at crime scenes under the new criminal justice system.

Other assistance seeks to improve communications between law enforcement officials in Chihuahua and cross-border communications with U.S. agencies, and supports state-level Joint Intelligence Task Forces (JITFs) formed by federal, state, and municipal forces to promote interagency coordination and more effective prosecution. The U.S. also provides assistance for the American Corrections Association (ACA) accreditation of prisons in Chihuahua, which establishes a set of standards to be met that human rights organizations have critiqued as being overly focused on infrastructure and administrative procedures; to date, seven Chihuahua prisons have been accredited.[62] Finally, INL supports “Culture of Lawfulness” programs to promote civil participation and government transparency, and Drug Demand Reduction programs aimed at adopting best practices “for the diagnosis and treatment of drug additions and supporting the creation of strategic pilot programs that can be sustained and replicated nationwide.”[63]

In a clear sign of the many problems that beset Juárez’s municipal police, U.S. training of this force has been limited by Leahy Law restrictions on U.S. training for security forces implicated in human rights violations. Currently, 63 percent of the police in Juárez are eligible for training, and 300 municipal police officers (out of a total force of 1,500 to 2,000) have been dismissed for alleged corruption in recent years. Consulate officials were hopeful that increased criminal prosecutions against police agents implicated in abuse could lead to use of a remediation process under the Leahy Law, which the State Department developed in 2015 to clarify when aid could be reinstated.[64]

Mexican Officials’ Reception of Deported Migrants

Juárez has seen a sharp drop in U.S. agencies’ deportation of Mexican migrants apprehended crossing the border, or in the interior of the United States. Between 2009 and 2010, the city’s then-mayor José Reyes Ferriz made multiple requests to U.S. authorities to stop deportations to the city due to high levels of violence and the mayor’s concern that deportees could be recruited by organized crime. In response, the U.S. government began returning Mexican migrants through other sectors of the border.[65] From 2009 to 2010, the number of Mexicans deported from the United States to Juárez dropped from 7.7 percent of all deportations (46,531 out of 601,356) to just 2.8 percent (13,555 out of 469,238). Although security has improved significantly, DHS continues to limit deportations to Juárez primarily to migrants who crossed the border in this sector, returning just 8,093 Mexicans to the city in 2015.[66]

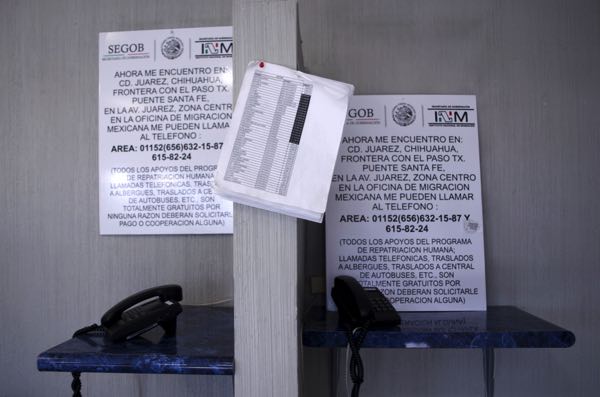

Migrants who are returned to Juárez do so under improved conditions. In addition to dramatically limiting nighttime deportations as stipulated by the new Local Repatriation Arrangements, as WOLA had the opportunity to observe, officials from Mexico’s National Migration Institute’s (Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) Humane Repatriation Program (Programa de Repatriación Humana, PRH) accompany repatriated Mexicans from the Border Patrol station on the U.S. side of the border and into Mexico. Once in Mexico, PRH officials provide migrants with a proof of repatriation document, which includes a photo and can be used as a form of identification to receive wire transfers and to purchase bus tickets. Migrants can also make phone calls at the INM office and are given some food and toiletries. PRH officials also coordinate with Grupo Beta (INM agents who provide basic services to migrants in need) to take migrants to the Oficina Municipal de Atención a Migrantes, an office established by the municipal government to provide services to migrants.

A young migrant is interviewed at the INM Humane Repatriation Program office in Juárez

A young migrant is interviewed at the INM Humane Repatriation Program office in Juárez

Created in 2013, this municipal office coordinates with the INM to provide food, a toiletries kit, legal services, medical attention, and support to buy a bus ticket for the return journey. The office also coordinates with the Mexican consulate in El Paso to recover documents or other belongings that might have been left behind or that were not returned to the migrant in the deportation process, and to provide advice in cases of family separation. Throughout the Mexican side of the border, this is the only office administered by a local government to provide services for migrants. While the service is a effort to encourage deported Mexicans to return to their hometowns or elsewhere in Mexico rather than stay at the border, it is also an important way to attend to repatriated Mexicans’ basic needs and ensure they have the necessary information to make decisions about their future.

Free telephone calls from the PRH office in Juárez allow deported migrants to notify their families of their location

Free telephone calls from the PRH office in Juárez allow deported migrants to notify their families of their location

Apart from government services, a Catholic Church-administered migrant shelter in Juárez provides temporary shelter, clothing, and medical services to deported migrants. The organization Integral Human Rights in Action-Binational Defense and Advocacy Program (Derechos Humanos Integrales en Acción, A.C.–Programa de Defensa e Incidencia Binacional, PDIB) also has staff present at the INM offices when Mexicans are repatriated to help migrants recover their belongings from U.S. agencies, document human rights violations and other abuses committed by Border Patrol and other U.S. and Mexican agencies, and to accompany migrants who seek to lodge complaints against U.S. officials.[67]

INM facility at the Paso del Norte border crossing

Areas of Concern

Increasing Recent Migration

As noted above, although overall migration to the El Paso sector is a small fraction of what it once was, the sector is now seeing some of the border’s strongest growth in arrivals from Central America. Central American unaccompanied children and family members are arriving in numbers similar to those seen in FY2014. Fiscal year 2016 was the second-heaviest year for arrivals of migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. As long as the violence pushing citizens from the Northern Triangle remains uncontrolled, we can expect large numbers of migrants, many seeking protected status, to continue journeying to the U.S.-Mexico border zone.

In 2015, as other WOLA reports have noted, a crackdown in Mexico brought a reduction in the number of Central American migrants who made it to the U.S. border.[68] What Border Patrol calls “Other Than Mexican” apprehensions dropped sharply from 2014 levels.[69] Three of Border Patrol’s nine sectors, however, saw no reduction in FY2015: Big Bend, Yuma, and El Paso (56.8 percent) experienced significant growth. The increases accelerated in FY2016, as indicated by Border Patrol data: unaccompanied child apprehensions in the El Paso sector were up 134 percent as compared to 2015 (the second-highest rate of increase of all nine sectors), and apprehensions of members of family units were up 364 percent (the highest rate of increase).[70]

Despite the recent high rates of increase, El Paso is nowhere near becoming an important destination for Central American migrants. From October 2015 through September 2016, unaccompanied child and family-member apprehensions in El Paso, though far higher than before, were still just about 11 percent what they were in the Rio Grande Valley sector.

Because the 2016 increase is so recent, research hasn’t yet revealed why so many more Central American migrants—or their smugglers—are choosing to cross the U.S.-Mexico border in this sector. Ciudad Juárez and its surrounding state of Chihuahua are about 500 miles farther from Central America than the state of Tamaulipas to the southeast.

The greater use of the Juárez-El Paso route could be a possible reaction to worsening organized crime-related violence in Tamaulipas, while security conditions have improved in Ciudad Juárez. Smugglers with migrants seeking to avoid detection could also be adopting new routes in order to avoid the increased U.S. security presence in the Rio Grande Valley sector, where the number of Border Patrol agents has increased and CBP has deployed new detection technologies.

So far, the arrivals of Central American children and families are not overwhelming Border Patrol’s ability to process them. Within 72 hours, the agency transfers unaccompanied minors to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services. At an ORR facility, these children receive care and some legal advice and are later placed with a family member or sponsor already in the United States, with whom they live while awaiting their immigration hearing. Families are either processed by ICE and then released to await their immigration hearing, or, in a small but growing number of cases, they are detained by ICE while they await a decision on their protected status.

All are given “Notices to Appear” (NTAs) before an immigration court to decide their cases. Here is where the backlog is most severe. Migrant advocates in El Paso told WOLA that, due to overflowing dockets, new arrivals given NTAs in April 2016 would have to wait two and a half years—until late 2018 or even early 2019—for their hearing dates. A final decision could take a year or more.

Abuse by U.S. Authorities

As discussed above, Border Patrol has a better relationship with the local community in the El Paso sector than in most other sectors. Abuses against migrants by Border Patrol agents are not widely reported. Nevertheless, some persistent problems continue to impact CBP (both Border Patrol and OFO) community relations.

Use of Force

A notable use-of-force case in the sector is the 2010 death of Sergio Adrian Hernandez Guereca, who was shot by Border Patrol Agent Jesus Mesa Jr. while with a group of other young people near a bridge between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. The agent alleged that he shot his weapon after being surrounded by a group of rock throwers, a claim that was contradicted by video footage of the incident. As Hernandez Guereca was inside Mexico when he was killed, a U.S. federal appeals court ruled in April 2015 that his family could not sue in the U.S. because the shooting’s effects were felt in Mexico, not the United States, and thus Guereca did not enjoy rights granted under the U.S. Constitution.[71] The family has petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case, affirming that “the U.S. solicitor general hadn’t offered a justification for the shooting or any reason why immunity should be granted to Border Patrol Agent Jesus Mesa”[72] The Supreme Court announced in October 2016 that it would consider the case, though a date for the oral argument has not yet been set.[73]

During the first eleven months of FY2016 (October 1, 2015 to August 31, 2016), out of 415 uses of less-lethal devices (such as the use of a baton or an electronic control weapon) by Border Patrol agents in all sectors, 33 were by Border Patrol in the El Paso sector. One agent in the sector used a firearm out of 12 uses of firearms by all Border Patrol agents. Uses of force by all CBP agents declined by more than 26 percent between FY2013 and FY2015, and assaults against agents also declined during this period. However, use of force by Border Patrol agents in all sectors has increased by 21 percent in FY2016 and assaults against agents also went up by 12 percent, with 404 assaults registered.[74]

Return of Belongings

When Mexican migrants are deported from the United States, the February 2016 Local Repatriation Arrangements discussed above require agencies to “take all feasible steps to ensure that property, valuables, and money” confiscated from detained migrants are returned prior to repatriation.[75] In practice, however, much remains to be done to make this a reality. Shortly before WOLA’s trip to El Paso, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of New Mexico filed jointly with human and civil rights organizations, including the PBID, a complaint against DHS on behalf of 26 people who were deported from the El Paso sector between 2015 and 2016. It cites a failure to return the complainants’ personal belongings, “exposing them to severe risk of harm upon their return to Mexico.”[76] Current policy establishes that when Border Patrol apprehends a migrant, all of his or her belongings, excluding U.S. dollars (which are deposited in an account), are left in Border Patrol custody and can be destroyed after 30 days. As multiple studies have shown, migrants routinely get transferred through different U.S. authorities’ custody, particularly ICE and the U.S. Marshals (for migrants who face jail time), which often results in their belongings being lost or destroyed, especially if a migrant is incarcerated for more than 30 days. Surveys have shown that 50 percent of migrants who went through Operation “Streamline,” a program developed in 2005 to deter migrants by criminally prosecuting them, reported the loss of some belonging. For other deportees, the rate of reported losses is 23 percent.[77] Although Operation Streamline is not used in the El Paso sector, illegal entry or re-entry prosecutions through the consequence delivery system (which applies criminal or administrative consequences to apprehended migrants) remain common.[78]

As WOLA has documented, the failure to return deported migrants’ belongings exacerbates their lack of access to services and safety networks.[79] A University of Arizona survey of deported migrants conducted between 2010 and 2012 found 39 percent reporting having their possessions taken and not returned.[80] Without important documents such as an identification card, cash, credit and debit cards, as well as mobile phones, too many migrants are left stranded in unfamiliar and often dangerous border cities with limited or no access to funds, and are often harassed and detained by local police for failing to provide an identification document. In the complaint regarding cases against CBP and ICE in El Paso, the charges allege that some of these agencies’ personnel mishandle personal belongings, fail to return them, and intimidate people who seek to recover them.

The problem seems particularly acute in the El Paso sector. According to the University of Arizona survey of deported migrants, 85 percent who crossed into El Paso had problems recovering their belongings, compared to 31 percent in Tucson and 3 percent in Laredo.[81]

In addition to the complications stemming from not having belongings returned, any money migrants had when they were detained is converted into U.S. dollars and given back when they are deported in the form of a U.S.-issued check that cannot be cashed in Mexico without paying exorbitant fees approaching 25 percent of the total value.[82] For a time, U.S. authorities experimented with prepaid debit cards as a way to address the problems with checks. However, these cards must be activated in the United States and present their own complications, including fees for withdrawing money or for consulting the account balance.

Ports of Entry

Another pressing issue for CBP in the El Paso sector is a troubling number of complaints of mistreatment by OFO agents stationed at the ports of entry. In May 2016 the ACLU of New Mexico and the Southern Border Communities Coalition (SBCC) filed a complaint on behalf of 13 border residents urging DHS to investigate abuse by OFO agents at ports of entry in El Paso and southern New Mexico. The complaint alleges excessive force, verbal abuse, humiliating searches, and intimidation to coerce individuals into surrendering their legal rights, including revoking visas, barring entry into the United States for five years, and revoking Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection (SENTRI) cards.[83] In several cases, the complainants reported that OFO agents discouraged them from filing a report or failed to adequately inform them how to file a complaint. In a separate case, in July 2016 a woman was awarded almost US$500,000 in damages by DHS after suffering several unwarranted and invasive body cavity searches when randomly stopped for inspection at an El Paso port of entry in 2012.[84]

Residents on both sides of the border meanwhile lament long wait times to cross the border from Juárez at El Paso’s three ports of entry. El Paso is the second busiest border crossing, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimates that one in every four jobs in El Paso is related to cross-border activity.[85] On some weekends and holidays, border crossers can be stuck in line for over three hours.

Long lines to cross into the United States at the Paso del Norte port of entry

Recent initiatives to reduce the wait times have yielded modest results. In the 2014 Homeland Security appropriations bill, the U.S. Congress authorized a pilot program allowing CBP to enter into public-private partnerships, enabling local governments and the private sector to invest in the ports of entry, including funding additional CBP officers and overtime pay.[86] El Paso was one of the first cities to enter into a partnership with CBP to fund the costs of additional agents.[87] Officials recently said that while the program had reduced wait times by 15 percent, much more needs to be done to continue to decrease times.

Federal and local officials are discussing different strategies, including the Cross-Border Trade Enhancement Act which would authorize CBP “to enter into agreements with certain persons for the CBP to provide customs, agricultural processing, border security, or inspection-related immigration services at a land border port of entry, subject to payment of a fee to reimburse the CBP for providing such services.”[88] In recent years, different versions of the Act have been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate several times by border representatives and senators, but it has not yet seen any votes in Congress.[89]

Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D-Texas), who represents El Paso, has prioritized initiatives to address wait times at the ports, launching the “#epbridges” initiative on his Facebook and Twitter accounts to gather feedback from local residents about their experiences at the ports and suggestions for improvement.[90] For its part, CBP continues the slow process of hiring additional agents for the ports of entry. While the 2014 appropriations bill funded the hiring of 2,000 CBP officers border-wide—there were 6,323 in 2015—background checks, polygraphs, and other procedures make the average hiring process take about a year and a half.[91] Meanwhile, DHS has identified about US$5 billion in construction and renovation needs at ports of entry nationwide.[92]

Problems at Checkpoints

Local organizations that WOLA met with also highlighted concerns about racial profiling and bias at Border Patrol interior checkpoints in southern New Mexico and the El Paso area, a persistent problem throughout the border region.[93] When they ask agents why they are stopped at a checkpoint, some residents report disrespectful language or harsh questioning.[94] Border Patrol agents told WOLA that what they mainly detect at the checkpoints are drugs and people—particularly foreign college students—who have overstayed their visas.

The Inhumane and Illegal Practice of Locking Up Families

Although most Central American families who cross into the United States through the El Paso sector are likely to be released and taken to a shelter, in 2014 CBP decided to send several women and their children to a quickly opened and poorly equipped family detention center in Artesia, in rural New Mexico, far from adequate access to legal and other services. Artesia, the site of a Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC), was opened as part of the Obama administration’s decision to detain families with the expectation of deterring other Central Americans from coming to the country, disregarding the fact that these mothers came to the United States with their children to seek protection.[95] Beyond Artesia, the administration began holding families in detention centers in Berks County, Pennsylvania; Karnes, Texas; and since December 2014 in a new family detention center with 2,400 beds in Dilley, Texas; these three centers are run by private corporations.[96]

In our February 2015 report, WOLA highlighted multiple concerns about the conditions and treatment within family detention centers.[97] Many of the families held in detention have been victims of horrific crimes and have valid claims for asylum in the United States. The prison-like conditions within the detention centers, lack of privacy, and allegations of abuse further traumatize children and their mothers. Because they present no public security or national security risk, the majority of these individuals should be released to await trial.

Artesia was closed at the end of 2014, although several of the women detained there were transferred to the center in Karnes. Dilley and Berks also continue to operate.[98] Texas authorities are trying to alter state rules to license family detention centers as child care facilities to get around legal challenges to detaining children.[99] In May, service providers reported a concerning increase in family detention in Dilley, where 600 mothers and their children were being detained.[100]

A view from the Paso de Norte bridge, above the Rio Grande

A view from the Paso de Norte bridge, above the Rio Grande

In December 2014, the ACLU filed a class action lawsuit challenging the family detention policy. In July and August 2015, District Judge Dolly Gee ruled that the family detention policy violated the 1997 Flores Agreement, a ruling that was upheld in July 2016 by the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Flores Agreement says that U.S. authorities should hold undocumented children in the least restrictive setting possible and favor releasing them. The ruling stipulated that the parents of children should be released as well, unless they present a flight risk or danger to the community. The rulings are an important step to limit family detention. However, several organizations have highlighted that the decisions “indicate some flexibility for the exceptional use of family detention in individual cases in ‘emergency’ situations defined by the Agreement, signaling that detaining a specific family for 20 days may not necessarily breach the Agreement if that is as fast as the government can accomplish release, in good faith, during an emergency.”[101] The government has misinterpreted this language to mean that a shorter average detention period puts it in compliance with the court’s order. Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson reaffirmed the administration’s belief that it is in compliance with the Agreement at an August 2016 event in Washington, DC, and confirmed that it will continue to detain families.[102] However, on September 30, 2016 the Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers created by DHS in 2015 recommended that DHS discontinue the use of family detention and that enforcement efforts should operate under the “presumption that detention is generally neither appropriate nor necessary for families.”[103]