Other ways to read this report:

Full-screen / mobile-friendly version at colombiapeace.org

Versión de pantalla entera / móvil en colombiapeace.org

Printer-friendly PDF in English

Versión PDF imprimible en español

This May, Colombia’s largest guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), will be 50 years old. Of all armed conflicts in the world that claim 1,000 or more lives a year, the one in Latin America’s third most populous country is the oldest.

In 2012, the Colombian government and the FARC began their fourth attempt to negotiate an end to the fighting. This time, the talks are beginning to stick: negotiators in Havana, Cuba have gotten significantly further than ever before. It is not unreasonable to expect an accord by the end of 2014.

The Havana talks have an agenda covering five substantive topics or political reforms, plus a discussion of how to operationalize what has been agreed. As of April 2014, after 22 ten-day rounds of talks, negotiators have reached agreement on two of these five substantive topics, and are nearing accord on a third.

Where the FARC Talks Stand (as of April 2014)

The negotiators’ agenda includes five substantive items, and one operational item:

✔︎ Integral agricultural development policy (land tenure and rural development)

✔︎ Political participation (guarantees for the political opposition, including former guerrillas)

❒ End of the conflict (transitional justice, disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration)

❒ Solution to the problem of illicit drugs (drug policy; currently under discussion)

❒ Victims (victims of the conflict)

and

❒ Implementation, verification, and ratification (how to cement peace accord commitments into law, then manage their fulfillment)

I. The U.S. Role Will Be Important

Vice-President Joe Biden visits Bogotá, May 2013.

Like all peace processes, the Colombian negotiations’ success will require international support, both political and financial. The most important international actor will be the United States, which over the past 15 years has been by far Colombia’s largest source of foreign assistance (US$9 billion since 2000). A large majority of this assistance has gone to Colombia’s security forces. U.S. aid has made both direct and indirect contributions to the armed conflict. It is strongly in the United States’ interest to be similarly supportive of Colombia’s effort to achieve peace, both during negotiations and especially, should the dialogues succeed, as the country navigates a complex post-conflict transition.

How a Peace Accord in Colombia Benefits U.S. Interests

- The hemisphere’s worst armed conflict would end, in fewer years than it would through battlefield defeat, thus improving regional security.

- It offers an opportunity to reduce illicit crop production.

- A group on the U.S. list of foreign terrorist organizations would cease to exist, and thousands of their members would move into legality.

- It creates opportunity for improved governance over historically lawless territories that have provided safe haven to terror groups and traffickers.

- It offers a chance to improve regional cohesion by cooperating, on a common project of support for the process, with Latin American countries that have had poor recent relations with Washington.

Diplomatic Support

While talks continue, the U.S. government can help keep the process on track through regular, public expressions of political support for Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos’s pursuit of peace through dialogue. High-ranking officials, including President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, have made regular statements of support for the talks, with public declarations averaging about one every two to three months.

How the United States Can Support Peace in Colombia

- Make regular and high-profile displays of support for the process.

- Accede to any request from the Colombian government to take actions that assist the process.

- Show flexibility if accords—especially the accord on drug policy—require shifts in U.S. strategy or assistance to Colombia.

- In the first several years of the post-conflict phase, maintain or even increase the generous levels of assistance that the United States has provided Colombia since 2000. Orient this assistance away from military and police aid, and toward peace accord fulfillment and strengthening of civilian institutions.

- Play a leading role in managing coordination among international donors, in order to guarantee that the greatest range of needs gets covered with minimal duplication.

- Employ the United States’ deep contacts with Colombia’s armed forces to help the military insitution smoothly weather what could be a painful post-conflict transition.

These public declarations should be more frequent. They are helpful to the dialogues because of their impact inside Colombia. Colombia’s most vocal opponents of the peace talks include influential figures like Álvaro Uribe, the former president, whom most Colombians regard to be very close to the U.S. government. (President George W. Bush presented Uribe, in January 2009, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.) By expressing its support for President Santos’s peace initiative, the Obama administration makes clear that it does not stand with the negotiations’ opponents.

Following President Santos’s December 3, 2013 visit to the White House, President Obama offered his strongest and clearest words yet of support for Colombia’s peace talks.

More frequent expressions of support are a policy measure that carries no financial cost, and very little political cost. In Washington, after 15 years of U.S. backing for Colombia’s security forces, a broad consensus appears to favor negotiations over continued fighting. While some more hawkish senators and representatives in the Republican Party have voiced reservations, they have done so infrequently, and usually with somewhat muted wording.

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida), angered by President Santos’s December 2013 criticism of U.S. policy toward Cuba, voiced concern about Santos’s negotiations with the FARC at a hearing later that month.

Flexibility on Drug Policy

One reason for this consensus is the negotiators’ agenda, which includes little that might run afoul of U.S. interests. A possible exception, though, is the agenda topic that the negotiators began in late 2013, and continue to discuss as this report goes to press (April 2014): drug policy.

For the past 30 years, the United States has sought to limit supplies of drugs leaving Colombia—principally cocaine—by emphasizing forced eradication of coca crops, military and police interdiction operations, and the capture, and subsequent interdiction, of traffickers. There is some likelihood that the Santos administration and the FARC might agree on some changes to drug policy that would require the United States to adjust its own strategy and its assistance. If that happens, the U.S. government must not react with rigidity. Supporting peace will require flexibility.

Flexibility will be needed most if Colombian negotiators agree to do away with a program to which the United States has devoted billions of dollars since the early 1990s: the eradication of coca, the plant used to make cocaine, by spraying it with herbicides from aircraft. The aerial fumigation program has sprayed more than three million acres of Colombian territory in the past 15 years, and the FARC demands that it end.

This demand is echoed by Colombian civil society groups, who point out the cruelty of spraying poisons over small farmers instead of offering them a functional government presence, and who allege that the spraying damages the environment and human health. Drug policy critics add that the spray program is ineffective, as it causes coca cultivation to disperse without achieving significant national reductions. Colombia’s post-2007 reductions in coca cultivation, they point out, occurred after the spray program underwent cutbacks after 2006. These arguments should make it relatively painless for the U.S. government to part with the spray program, should the peace accords require it. Still, accommodating this change may require a show of flexibility from officials and agencies who continue to view fumigation as an effective supply reduction tool.

During his December 2013 Senate confirmation hearing, the incoming U.S. ambassador, Kevin Whitaker, gave an overview of some challenges Colombia’s peace process will face. The ambassador-designate expressed concern that guerrilla negotiators seek to end the U.S.-backed aerial herbicide fumigation program, which he said “would be a great mistake.”

A second issue likely to arise in a drug-policy accord is extradition. Nearly every FARC leader of any consequence is wanted by U.S. courts or prosecutors to face drug trafficking charges. The U.S. executive branch has no power to withdraw these extradition requests. FARC leaders, however, will not demobilize without guarantees that Colombia’s government will not extradite them to the United States, at least as long as they are honoring their peace process commitments.

If Colombia does not fulfill the United States’ outstanding extradition requests for FARC leaders, it is up to the President and the State Department to decide whether this has any effect on U.S.-Colombian relations. The most likely outcome is that non-extradition would have no impact on bilateral relations. However, the U.S. judiciary’s extradition requests for demobilized FARC leaders will remain on the books, always hanging over Colombia’s post-conflict reality.

The key question is whether non-compliance with extradition requests has any effect on U.S.-Colombian relations. There are precedents for this having no effect. In 2011, Colombia extradited Venezuelan narcotrafficker Walid Makled to Venezuela, though he was also wanted by U.S. justice. In 2009, Colombia’s Supreme Court halted the extradition of paramilitary leaders participating in transitional justice processes. Neither case affected U.S.-Colombian relations.

The key question is whether non-compliance with extradition requests has any effect on U.S.-Colombian relations. There are precedents for this having no effect. In 2011, Colombia extradited Venezuelan narcotrafficker Walid Makled to Venezuela, though he was also wanted by U.S. justice. In 2009, Colombia’s Supreme Court halted the extradition of paramilitary leaders participating in transitional justice processes. Neither case affected U.S.-Colombian relations.

Beyond drug policy, the FARC talks call on the U.S. government to show new flexibility on its policy toward Cuba. If the negotiators in Havana succeed in reaching an accord, the Cuban government’s prudent role as one of the two “guarantor nations” of the process (the other is Norway) will undo what little pretext remains for Washington maintaining Cuba, alongside Iran, Sudan, and Syria, on its list of the world’s terrorism-sponsoring states. Cuba is working to ease the demobilization of the Western Hemisphere’s largest entry in the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations. The State Department should show support for the talks by removing Cuba from a list to which it no longer belongs.

“The U.S. State Department has admitted that Cuba no longer supports terrorism and armed insurgency; thanked Cuba for helping to secure the release of a U.S. citizen in Colombia; and lauded the Cuba-sponsored peace talks between Colombia and the FARC. All the while, it has continued to designate Cuba as a State Sponsor of Terrorism.”

– Ana Goerdt, WOLA Program Officer for Cuba, October 2013

II. The Remainder of the Talks

A FARC-government accord on drug policy is likely, but the Havana talks will still have a lot of ground to cover. One question is how an eventual peace accord is to be ratified, or given force of law. The FARC wants a constitutional convention to rewrite Colombia’s governing charter, while the government favors letting voters approve the peace accords in an up-or-down referendum. This operational question is scheduled for discussion at the end of the peace talks, as part of the final agenda point. Two even thornier questions must be addressed first: how to provide for the conflict’s victims, and how to bring to justice those who have committed crimes against humanity.

Victims

The FARC is responsible for thousands of non-combatant killings, kidnappings, forced displacements, landmine casualties, child combatants, and other acts that have left behind a large number of victims. The group’s leaders and negotiators appear to be in denial about this. Their statements often convey the message that “we are victims too.” Only in recent months have FARC negotiators, in interviews with journalists, even begun to hint at the need to provide reparations and restore dignity to their victims.

Numerous observers have noted that the moment the FARC publicly exhibits humility and asks forgiveness of its victims, the peace process will have crossed a crucial milestone after which a successful accord will be virtually certain. FARC negotiators say that they may be prepared to make such a statement, but not until the peace negotiations reach this agenda topic. “I don’t have the formula,” FARC negotiator Pablo Catatumbo told Colombia’s El Espectador newspaper in November 2013. “This is an issue that we will take up at the negotiating table in due time. The only thing I want to say is that we are neither insensitive nor cynical about this.”

In a video clip that angered many, FARC negotiator Jesús Santrich was asked in Oslo whether the guerrillas are prepared to ask their victims’ forgiveness. Singing the refrain of a popular Cuban song from the 1940s, Santrich laughingly replied, “Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps.”

The FARC is not the only offender who must show more contrition. FARC leaders correctly point out that other armed groups have caused massive victimization, even exceeding their own grim toll. Taking together guerrillas, paramilitaries, and the state security forces, more than six million Colombians—of a population of 47 million—have lost loved ones; been kidnapped, maimed, or tortured; been displaced; or otherwise suffered directly from the conflict.

Victims deserve recognition and dignified treatment from the state, and from those who wronged them. They deserve reparations, both individually and as communities, as foreseen in a 2011 Victims’ Law that has barely begun to be implemented. They need efforts to reconcile them with their demobilized victimizers, wherever possible, since they must continue to live together in the same communities.

Part of the effort to restore victims is a truth commission, a mechanism foreseen in a constitutional amendment, the “Legal Framework for Peace,” that Colombia passed in 2012. This commission’s mandate must include crimes committed by all sides, and it must have sufficient autonomy, budget, protection, and time to do its work.

What a Strong Truth Commission Needs

- Independence and Autonomy. Commissioners and their staff should be chosen through a transparent process according to clear criteria. Once hired, it should be very difficult to fire them. They and their families should have utmost security protection. They should be able to manage their budget without outside interference.

- Sufficient Budget and Staff. The Commission should have ample manpower, technology, and transportation. Truth will not be revealed on a shoestring.

- A Long Timeframe. A short mandate with an ever-looming deadline is a backhanded way to ensure that truths remain hidden. The Commission will need time.

- Constant Consultation with Victims. The Commission must constantly seek input from their main stakeholders: Colombia’s associations of victims. This formal, regular consultation process must include women, indigenous, and Afro-Colombian victims.

Transitional Justice

Past peace processes, in Colombia and elsewhere, have included little or no punishment for even the worst human rights abusers. In El Salvador, Guatemala, and Northern Ireland, amnesty from prosecution or release from prison was granted in exchange for groups’ demobilization. In South Africa, amnesty came after public confessions.

Today, though, as international human rights norms have evolved, governments can no longer entice armed group members to demobilize by offering amnesty, at least not to the worst abusers in their ranks. Colombia is a signatory to the 2002 Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands. If this court determines that a signatory country is not sufficiently punishing those responsible for crimes against humanity, it can call for those individuals’ arrest and put them on trial.

Colombia pursued an alternative punishment standard in the mid-2000s, when it demobilized pro-government paramilitary groups. The 2005 “Justice and Peace” law required the worst paramilitary violators to confess to crimes and receive sentences of five to eight years. The confessions revealed the locations of thousands of graves, gave evidence that could potentially solve thousands of homicides, and helped to launch prosecutions of hundreds of politicians who allied themselves with the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) paramilitary organization.

The results of the prosecution effort, however, have been scarce. After eight years, the number of convicted paramilitaries is minuscule, and many members of the drug-funded death squads may soon be set free, having served their time without ever completing their judicial processes.

Today, Colombia’s peace process is the world’s first to involve a Rome Statute signatory country, and amnesties for crimes against humanity are not allowed. The ICC’s prosecutor has already warned Colombia that its negotiators in Havana must not agree to an amnesty for the worst rights violators. In a July 2013 letter, Fatou Bensouda made clear that even an arrangement that puts abusers on trial, but suspends sentences afterward, would not be stringent enough to forestall independent action from the Court.

“I have come to the conclusion that a punishment that is grossly or manifestly inadequate … would invalidate the authenticity of the national judicial process. … The suspension of sentences would go against the ends and purposes of the Rome Statute, given that it would impede, in practice, punishment of those who have committed the most serious crimes.”

Still, President Santos has not taken amnesty or suspended sentences formally off the table. When the U.S. Congress passed aid budget legislation in early 2014 that would freeze some military assistance if Colombia amnesties serious abuses, Colombian supporters of the negotiations protested—though they insisted that there would be no amnesty.

In his speech before the UN General Assembly in September 2013, President Santos made clear to the international community that some crimes will have to go unpunished.

The 2012 Peace Framework constitutional amendment appears to make it permissible for Colombia to pass a law that would suspend sentences, or at least impose lenient alternatives to imprisonment, for the worst violators in both the FARC and the armed forces. If that happens, Colombia may find itself on a collision course with the International Criminal Court—unless it finds some form of punishment that satisfies the ICC while still convincing guerrilla leaders that it is worth their while to demobilize. This will be a difficult needle to thread.

What To Do With the Worst Rights Violators?

Transitional justice is the most difficult remaining issue facing the negotiators. At its heart is a vexing question: if international human rights standards prohibit amnesties for the worst violators, and perhaps even prohibit suspended sentences after a trial, then what sort of imprisonment, or “denial of liberty,” can Colombia implement without discouraging guerrillas from demobilizing?

After former guerrillas accused of crimes against humanity admit guilt, undergo confessions, and make reparations to victims, they could face an option like one of the following:

- Reduced sentences in regular prisons. This is what Colombia applied to pro-government paramilitary leaders during the mid–2000s “Justice and Peace” process. FARC leaders are unlikely to agree to this, though it could be made more palatable if Colombia applies the same procedure to members of the security forces who gravely violated human rights, and members of Colombia’s economic elite who masterminded violations and sponsored paramilitarism.

- Reduced sentences in an alternative facility. FARC leaders accused of grave abuses would live in an area, or areas, in which they could enjoy some freedoms—to receive visitors, to build their political movement, to speak to the press and communicate on the internet—but from which they could not leave. (A similar arrangement was the “Casa de Paz,” a house north of Medellín from which, in the mid–2000s during the end of his prison term, captured ELN leader Francisco Galán was able to receive visitors and serve as an intermediary for possible talks with the guerrilla group’s leadership. The perimeter of this house was under constant police guard.) This option could be attractive to demobilized FARC leaders who, in the first years after an accord, might need a secure place from which to build a future political movement.

- Suspended sentences after full confessions and reparations, with a ban on political activity for a certain number of years. It is not clear whether this option would satisfy the International Criminal Court, or whether it would satisfy FARC leaders with political ambitions.

This question is so complex, however, that the formula the negotiators ultimately choose could be something else entirely.

It may be possible to convince demobilizing guerrillas to pay a penalty for crimes against humanity, if members of the armed forces, and civilian backers of paramilitary atrocities, do the same. Many high-ranking officers stand accused of aiding and abetting paramilitary groups when they were at the height of their brutality. Many more stand accused of killing over 3,000 civilians, most of them on over 1,500 alleged occasions between 2004 and 2008. This is known in Colombia as “false positives,” a scandal in which soldiers fabricated combat killings in order to reap rewards for high body counts.

A significant portion of armed-group members the Colombian Army claimed to have killed in the mid-2000s may have actually been civilians, according to data from prosecutors. Some of these “false positive” prosecutions are proceeding, and civilian courts have sentenced hundreds of soldiers and a few officers. But most cases, after many years, remain in their initial phases.

Colombia’s military, however, continues to deny the scale and seriousness—and sometimes even the existence—of “false positives” and other abuses. While an agreement that holds officers accountable in exchange for reduced sentences might convince the FARC to accept a similar standard, it will require firm civilian leadership to ensure that members of the politically powerful armed forces, in what they may perceive as their moment of victory, undergo a series of public confessions, apologies, and trials in civilian tribunals.

Public Opinion and Political Opponents

Even as it navigates these thorny questions, the peace process must continue benefiting from public support inside Colombia. If it becomes unpopular, it risks becoming unattainable. During its first year and a half, the process itself has been reasonably popular. Polling in Colombia routinely shows 55-65 percent of respondents approving of the negotiations. A similar majority, however, normally expresses doubt that they will succeed. And when asked whether they would support giving ex-FARC members amnesty, or the ability to run for Congress, opposition reaches 75-85 percent. (For the results of several polls taken over the duration of the peace process, see the Peace Timeline at WOLA’s colombiapeace.org website.)

The process has gone far slower than the Colombian government initially advertised. This CNN interview is from September 2012.

The process has gone far slower than the Colombian government initially advertised. This CNN interview is from September 2012.

For its part, the Colombian government has not always managed expectations well. President Santos’s declarations that the talks would be completed by November 2013 hurt their credibility when that milestone passed with only two agenda items complete. At the same time, the Colombian government’s communication and messaging have been rather bland and subdued, while the FARC and the talks’ opponents, especially Former President Uribe, have used broadcast and social media to maximum effect.

Speaking in Medellín on February 8, 2014, Former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe, a fierce opponent of President Santos’s negotiations with the FARC guerrillas, alleged that even the worst guerrilla violators will “leave the jungle, go to Havana, and go on to Congress without passing through jail.”

The public opinion environment is further complicated by campaigning for March 2014 legislative and May 2014 presidential elections, in which President Santos is running for a second term. President Santos is the only viable presidential candidate promising to continue the peace talks. If the FARC wants the process to continue after May—and it appears that they do—they know they must continue progressing toward accords, thus giving the peace talks the impression of momentum needed to keep public opinion favorable.

If peace talks should fail, it will take many bloody years to defeat the FARC on the battlefield. This chart, from Colombia’s Peace and Reconciliation Foundation, shows the number of FARC “armed actions” in recent years. The guerrillas are weaker than they were a decade ago: most of the more recent “actions,” like sabotage of infrastructure or detonation of landmine fields, are smaller in scale, and occur in more remote areas. But they are still capable of several actions per day all around the country, despite an enormous effort by the security forces. On the battlefield, the conflict is decidedly not in the “home stretch.”

If peace talks should fail, it will take many bloody years to defeat the FARC on the battlefield. This chart, from Colombia’s Peace and Reconciliation Foundation, shows the number of FARC “armed actions” in recent years. The guerrillas are weaker than they were a decade ago: most of the more recent “actions,” like sabotage of infrastructure or detonation of landmine fields, are smaller in scale, and occur in more remote areas. But they are still capable of several actions per day all around the country, despite an enormous effort by the security forces. On the battlefield, the conflict is decidedly not in the “home stretch.”

Should the talks reach a final accord, it would likely be ratified in a referendum. Even if the Colombian public is uncomfortable with some of the concessions granted to the FARC—a group that, because of its record of abuses, is very unpopular in mainstream political opinion—it is likely to say yes to a deal that promises to remove the FARC from the scene after 50 years.

ELN leaders Pablo Beltrán, Ramiro Vargas, Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista aka Gabino, and Antonio García, in 2011.

Waiting For the ELN

The FARC is not Colombia’s only leftist guerrilla group. The National Liberation Army (ELN), also founded in 1964, has about 1,000–2,000 fighters active in some parts of the country. Though FARC and ELN have fought at times, their leaderships appear to be cooperating at present, as evidenced by several recent joint declarations.

The Colombian government has been discussing the possibility of talks with the ELN, and the guerrillas have repeatedly issued statements indicating their willingness to negotiate. Uruguay’s government has offered its territory as a venue for eventual talks.

But talks have not begun, and as of April 2014 it is not clear when they might start. Neither side publicly acknowledges the reasons for the holdup. The most likely causes for the delay, though, are the following:

- The government’s pre-condition that the ELN release all kidnapped individuals in its custody. The FARC met this condition in early 2012. The ELN may have released its last hostages in December 2013, but it is still unclear whether they are holding more.

- The ELN’s likely desire to include Colombia’s mining and energy policy on the negotiating agenda. While this is off the table at the FARC talks in Havana, the ELN has long called for a greater state role in these industries, and has been dominant in the Arauca oil producing region. Today, though, these industries make up most of Colombia’s export revenue, and the government is reluctant to agree to changes.

- The ELN’s likely insistence on a bilateral cease-fire while talks occur, a condition that the government did not concede to the FARC.

- The ELN’s demand that civil society be included in its talks. This is a longstanding demand, but it remains unclear how to operationalize it, or even who constitutes “civil society.”

- The ELN leadership’s decisionmaking process. The group, considered less hierarchical than the FARC, is believed to make its decisions by consensus. Building consensus across far-flung front leaders and a five-member “Central Command,” especially on an issue like whether to negotiate, can take a great deal of time.

- The relationship to the FARC talks. With the FARC talks now quite far along, it is unlikely that the ELN would join in the Havana process. In separate talks, the ELN would presumably have to ratify, rather than revisit, what has been agreed in Havana.

Negotiating with the ELN is complicated and slow, but necessary. If Colombia reaches an accord with the FARC while the ELN remains active, the smaller group could grow quickly as it absorbs thousands of dissident FARC leaders and fighters, and peace will remain far off.

III. Likely Post-Conflict Challenges

April 2013 pro-peace march. Photo from Bogotá city government.

Should the negotiators reach a final accord, there will be an outburst of optimism. Colombia will have much to celebrate. But the day after the accord is signed and the photos are taken, the panorama will grow more complicated than it was during the talks. Colombia will have to fulfill some very ambitious commitments laid out in the peace accords, while at the same time demobilizing tens of thousands of fighters, attending to victims, and bringing the state into historically ungoverned territories at risk of future flare-ups of violence.

Implementing the Land and Rural Development Accord

Rural poverty and unequal land distribution have been at the core of the FARC conflict. Preventing further rural violence, and addressing persistently high levels of poverty in the countryside, will mean working assiduously to fulfill, to the letter, the commitments made in the peace accord on land and and rural development. While we do not know the full details of this accord’s contents, we can be certain that protecting and encouraging small landholding producers will mean confronting the interests of some large landholders who have long been accustomed to enjoying near-absolute local power.

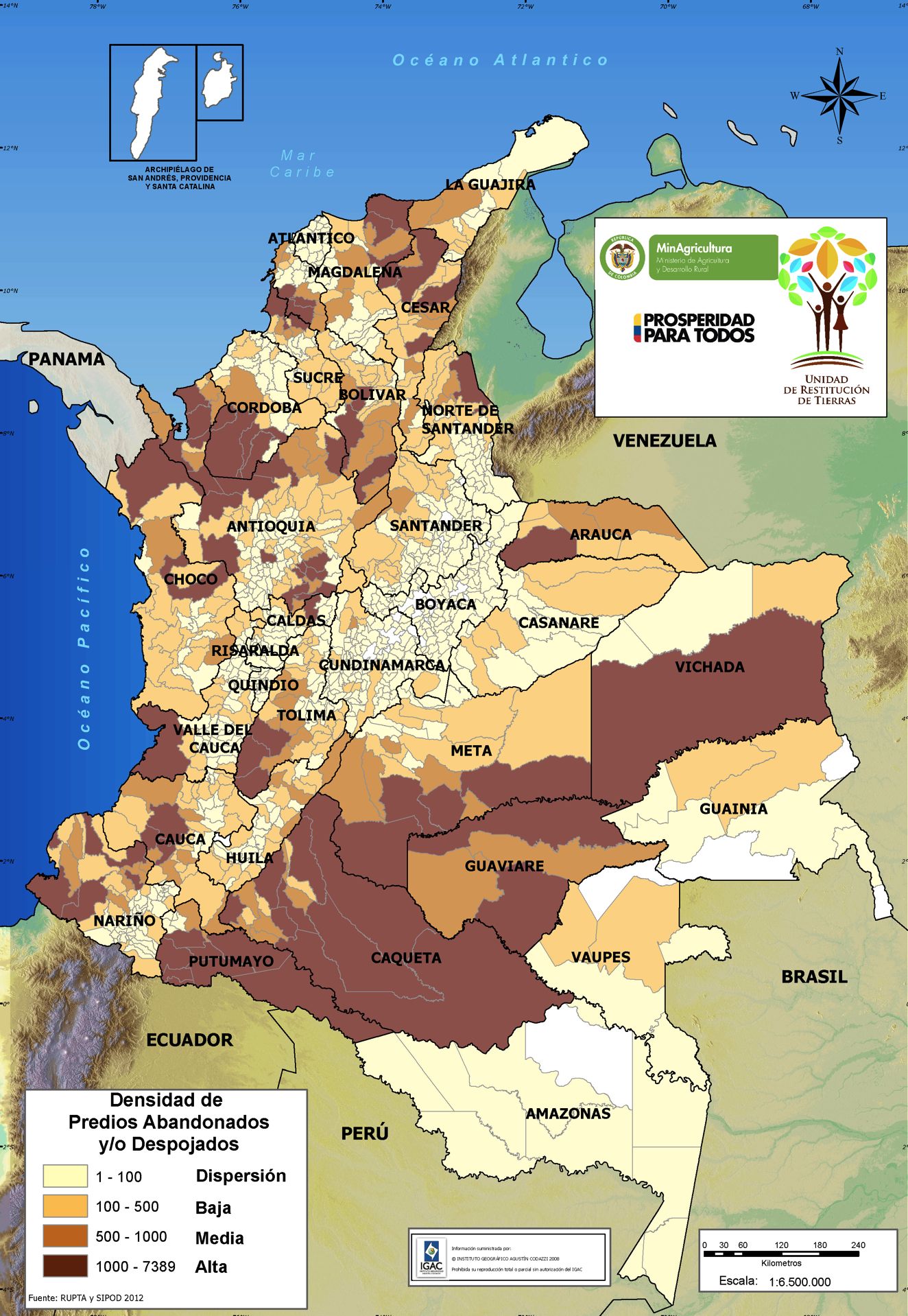

In this map from the Colombian government’s land restitution unit, municipalities appear darker if they have more landholdings that were abandoned, or forcibly taken, as a result of the armed conflict. The phenomena of abandonment and dispossession are pervasive throughout the national geography.

In this map from the Colombian government’s land restitution unit, municipalities appear darker if they have more landholdings that were abandoned, or forcibly taken, as a result of the armed conflict. The phenomena of abandonment and dispossession are pervasive throughout the national geography.

Confronting entrenched interests in Colombia’s distant regions is something that Bogotá, despite declared good intentions, has little record of doing. The 2011 land restitution law is supposed to return land to as many as 200,000 dispossessed campesino families in Colombia. So far, though, Colombia has made little progress toward this target, as the Latin America Working Group, Human Rights Watch, and other journalists and researchers have observed. So far, the land restitution effort has been another example of the gap between good intentions in Bogotá and willingness to take on local power elsewhere in the country. This persistent gap is cause for concern if Colombia is to face similar challenges implementing a land and rural development accord.

At a conference in Washington hosted by WOLA in January 2014, Yamile Salinas of Colombia’s INDEPAZ think tank discussed the slow implementation of the country’s 2011 land restitution law, and how it portends the challenges that will confront a future peace accord on land and rural development.

Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration

FARC negotiators have voiced some reluctance to turn in their weapons after signing a peace accord. Still, disarmament—or some form of putting weapons “beyond use,” as was done in Northern Ireland—plus some form of demobilization, will undoubtedly be immovable Colombian government conditions for ending the war. Once collective demobilizations take place, Colombia must contend with a wave of former fighters, most of whom have almost no education or marketable skills and severe cases of post-traumatic stress.

This will not be the the first such wave that Colombia has faced. Between the paramilitary demobilizations of the “Justice and Peace” process and the individual guerrillas who have demobilized at rates over a thousand per year, Colombia has had to reintegrate over 55,000 armed group members since 2002. Its record is mixed. There has been a great deal of learning since the initial years of two-year stipends, poor record-keeping, and low budgets. The Presidential Reintegration Agency now gives ex-fighters employment training, psychosocial support, and basic education over a longer time period. Still, too many of them slip out of the system, and generate new violence when they fall back into criminality.

Colombia’s demobilization and reintegration programs have been more successful than those of most other countries, but a large portion of the demobilized have still fallen out of the system. A future reintegration of FARC combatants will need to maintain a much higher participation rate.

Colombia’s demobilization and reintegration programs have been more successful than those of most other countries, but a large portion of the demobilized have still fallen out of the system. A future reintegration of FARC combatants will need to maintain a much higher participation rate.

After an accord with the FARC, Colombia and international donors must place highest priority on preventing mid-level guerrilla commanders from opting out of demobilization. The most senior FARC commanders, after decades in the jungle, will most likely stay demobilized as they involve themselves in politics or simply retire. Rank-and-file fighters, many of them minors, will be likely to take advantage of educational and vocational opportunities through reintegration programs. The most problematic former guerrillas will be those who have had some middle-ranking position of authority, or involvement in fundraising, especially in areas where the FARC controls illegal income sources like drugs, unlicensed mining, or extortion.

These individuals would be demobilizing with a large head start in the criminal underworld, controlling key trafficking corridors and enjoying extensive criminal connections. They pose the highest risk of returning to their zones of operations, rearming, and generating new violence as the heads of emerging criminal groups. These groups may not call themselves “FARC,” but as they compete for territory and illicit income sources, they could be at least as violent.

A motorcycle bomb that detonated in the southwestern Colombian town of Pradera on January 16, 2014, the day after a 30-day FARC truce ended, raised concerns about the guerrillas’ command and control, and about mid-level commanders’ commitment to the process. The FARC negotiators in Havana denied knowledge of the attack, which killed one person and wounded 56, and the group’s leadership later “repudiated and condemned” it.

A motorcycle bomb that detonated in the southwestern Colombian town of Pradera on January 16, 2014, the day after a 30-day FARC truce ended, raised concerns about the guerrillas’ command and control, and about mid-level commanders’ commitment to the process. The FARC negotiators in Havana denied knowledge of the attack, which killed one person and wounded 56, and the group’s leadership later “repudiated and condemned” it.

Avoiding this outcome will require a major effort to improve security and governance in zones where trafficking is profitable, state presence is weak, and armed groups predominate. Presumably, the immediate aftermath of a peace accord is a moment during which the government can enter these territories and establish itself with a minimum of violent resistance. Still, an effort to fill territorial governance vacuums will first require clarity about military and police roles, and second, a commitment to ensure that the resulting government presence is overwhelmingly civilian. Simply deploying soldiers into formerly FARC-controlled areas is not enough.

This image juxtaposes the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation’s 2013 map of FARC fronts with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s 2012 map of coca cultivation. It shows many FARC fronts active in coca production zones, and several others operating along rivers, coastlines, and border areas that are lucrative trafficking corridors. If the FARC leadership signs a peace accord, it will be difficult to convince many of these fronts’ members to walk away from this income stream and demobilize.

Colombia already witnessed this phenomenon in the aftermath of the 2003-2006 demobilization of paramilitary groups. Many mid-level paramilitary leaders returned immediately to the drug business, this time as the heads of small armies that, through corruption and intimidation, continue to control entire regions. These “bandas criminales,” or “bacrim” as Colombia’s security forces call them, could combine with structures led by former mid-level FARC figures (which some analysts are already calling “farcrim”) to form the new face of narcotrafficking, and of armed conflict, in post-FARC Colombia.

“Criminal bands” with roots in 1980s–2000s paramilitary groups, like the “Urabeños” and the “Rastrojos,” are active in about as much territory as the FARC.

Governance in Ungoverned Areas

In fact, even if civilians are part of the package, merely injecting a government presence into historically violent and ungoverned areas is not enough. These territories are not blank slates. They have local governments, producers’ associations, Afro-Colombian and indigenous reserves and organizations, victims’ groups, and similar civil society structures. Any post-conflict effort to improve governance must work hand in hand with these organizations, making their strengthening a central goal. The experience of initiatives that combine economic development with peace-building and civil society strengthening, like the Magdalena Medio Peace and Development Program in north-central Colombia, is very instructive.

A non-governmental effort backed mainly by foreign donors, the Magdalena Medio Peace and Development Program achieved remarkable results in a very conflictive part of Colombia, by combining peace-building efforts with participatory economic development projects. The Magdalena Medio experience holds lessons for post-conflict efforts to improve governance throughout Colombia.

A non-governmental effort backed mainly by foreign donors, the Magdalena Medio Peace and Development Program achieved remarkable results in a very conflictive part of Colombia, by combining peace-building efforts with participatory economic development projects. The Magdalena Medio experience holds lessons for post-conflict efforts to improve governance throughout Colombia.

Building peace and governance in historically conflictive zones cannot happen in a top-down, imposed fashion. In areas that have never known a government, the state’s credibility will depend not just on the resources it employs, but on the extent to which it is willing to listen to, and share responsibility with, civil society.

Bringing good governance and development to Colombia’s historically conflictive areas requires leadership from victims and civil society. Speaking at a January 2014 conference sponsored by WOLA, Fr. Francisco de Roux, S.J., the Jesuit provincial in Colombia and former director of the Magdalena Medio Peace and Development Program, outlined some guiding principles.

IV. The United States’ Post-Conflict Role

2013 graduates of El Salvador’s Civilian National Police Academy, which received generous U.S. support during that country’s 1990s post-conflict period.

Helping Colombia to meet these post-conflict challenges will be expensive, at times frustrating, but absolutely necessary. U.S. officials like Secretary of State John Kerry and USAID administrator Rajiv Shah have indicated a willingness to support Colombia generously at this phase. Their statements have offered no detailed sense of U.S. plans, which is unsurprising since the peace accords’ contents are not yet known.

While in Bogotá in August 2013, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry voiced strong support for Colombia’s peace process, and indicated that Washington is ready to assist a possible post-conflict phase.

Still, U.S. assistance programs often move slowly, and the time to start planning for post-conflict support is fast approaching. Above all, budget planners must prepare to provide support at the same, or greater, levels of assistance that Colombia has been receiving since the mid-2000s. The past several years’ steady 10-15 percent annual reductions in assistance to Colombia would have to end, and reverse, upon the signing of a peace accord.

The list of priorities that this renewed aid could support is long, and this report has discussed many of them. They include costly efforts like bringing government into lawless areas; demobilizing and reintegrating combatants; assisting displaced populations’ return; protecting rights defenders; helping to fulfill accords on land, political participation, and victims; supporting transitional justice mechanisms and a truth commission; and backing international verification and monitoring efforts, whatever form they take.

While not every agency or institution depicted here has veto power, the concerted opposition of one or more, absent strong leadership at the highest levels, could cripple U.S. support for Colombia’s peace process.

While not every agency or institution depicted here has veto power, the concerted opposition of one or more, absent strong leadership at the highest levels, could cripple U.S. support for Colombia’s peace process.

Military aid is a far lower post-conflict priority in a country that already spends US$14 billion per year on its own defense sector. However, the United States can play an important role in easing the military’s transition to a post-conflict Colombia. A successful peace accord may mean the sudden disappearance of what has been the Colombian armed forces’ principal mission during the past 50 years. Latin America’s second-largest armed forces (and largest army) will be facing strong pressures—including from the country’s tax-paying business community—to reduce its size and budget. With organized and common crime posing the principal security threat, attention and resources may shift from the armed forces to the police and the justice system. Colombia’s National Police could even be moved out of the Defense Ministry and into a new public security ministry, as has happened nearly everywhere else in Latin America since the 1980s.

Helping Colombia’s Military Adjust

For Colombia’s influential military, these adjustments will be painful. The institition may resist them in ways that complicate peace accord implementation. The country’s civil-military relationship could enter a period of severe crisis as peace threatens longtime military prerogatives. It is at these moments that the United States can leverage its deep relationship with the Colombian armed forces to ease difficult transitions.

At times in recent years, U.S. policymakers have allowed their analysis of Colombia to be influenced by counterparts in Colombia’s largely pro-U.S. military, especially on human rights. This cannot happen during the post-conflict period. Instead of advocating military priorities, U.S. defense and diplomatic officials’ post-conflict interactions with Colombian military counterparts must encourage professionalism and the primacy of elected civilians’ decisions.

Supporting International Verification and Monitoring

Finally, in addition to providing aid and advice to Colombia, the United States can be central to guiding the international community’s post-conflict support. This would include generously supporting an international verification and monitoring presence with a strong mandate. We do not recommend the specific international organization that should manage this mission or presence. The UN has by far the most experience with such missions. The OAS, which still maintains a verification mission set up during the paramilitary demobilizations, has more infrastructure and presence in far-flung regions where peace accord implementation will be most challenging.

What an International Verification and Monitoring Mission Could Do

- Be the arbiter of whether peace accord commitments are being fulfilled.

- Manage and verify demobilization of combatants.

- Offer expertise and technical support to reintegration programs.

- Supervise the formation of a truth commission, transitional justice tribunals, and, if required, facilities for the worst human rights violators’ “deprivation of liberty.”

- Offer expertise and technical support to fulfillment of accords on rural development, political participation, drug policy, and victims.

- Assist the return of displaced persons.

- Assist post-conflict transitions in the security forces.

- Accompany organizations of victims, displaced persons, women, land-rights defenders, human rights defenders, indigenous people, Afro-Colombian groups, labor, and others.

- Serve as a forum to coordinate international donors, thus avoiding duplication of efforts.

Helping to Coordinate International Donors

The United States can also help guide international community backing for post-conflict Colombia by supporting coordination between donor nations. Resources are too scarce to duplicate efforts, and a consciously planned division of labor can help ensure that no acute needs go unmet. U.S. officials should support, and if needed organize, conferences and other mechanisms to enable smooth, efficient, and effective communication and coordination between donors.

Colombia’s Neighbors (Brazil, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela) Can Help Solidify Peace By:

- Continuing to make frequent public expressions of solidarity and support for ongoing negotiations.

- Improving public security in border zones, making them inhospitable to potential Colombian “spoiler” groups.

- Acting to reduce armed or “spoiler” groups’ weapons trafficking through their territory into Colombia, or drug trafficking through their territory from Colombia, including punishment of corrupt officials who aid or abet such activity.

- Facilitating the post-conflict return of Colombian refugees.

These conversations and plans should start now, because this peace process is looking ever more like the real thing.

Supporting post-conflict Colombia must start the moment an accord is signed. In a situation where criminality and weak governance threaten constantly to trigger new forms of violence and conflict, delay could be disastrous.

Colombia and its international supporters must be prepared to start work on day one. In order to start quickly, planning for the post-conflict period must begin now, even while the talks’ success is not completely certain. The conversation about how to help begins now.

WOLA thanks the Kingdom of Norway for the support that made this publication possible.