(AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

(AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

In 2016, after various failed efforts with devastating human consequences, Colombia signed peace with guerrilla group the FARC, ending a protracted conflict that violently raged on for over half a century. In the end, the conflict resulted in more than 23,000 selective assassinations, 27,000 kidnappings, 260,000 deaths and 8 million registered victims.

The bulk of the fighting, displacement and abuses were related to armed groups vying for control of land in areas with weak or no state presence. For example, atrocities like the May 2002 Bojaya massacre—in which over 80 Afro-Colombian civilians were incinerated after FARC guerrillas threw a pipe bomb at the church where they were taking refuge from the fighting—were concentrated in rural Colombia.

Afro-Colombian and indigenous populations have long inhabited the most remote, geographically hard to access and biodiverse areas of the country. Yet it wasn’t until 1991—when Colombia’s constitution finally recognized the plural ethnicity of the country—that these populations were able to legally claim their collective land titles. Despite this formal protection, Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities have been disproportionately victimized by special interests propping illegal armed groups’ thirst for land in order to carry out illegal economies and development projects without the consent of local communities.

Within this context, Colombia’s peace accord attempts to balance international standards of justice with a necessary demobilization of combatants in order to end the fighting. In pursuit of that balance, it is innovative in many respects: it transversally safeguards the rights of ethnic minorities, integrates women and gender rights, and includes commitments geared towards resolving the issue of illicit drugs.

At its core, this innovative approach to peace is largely due to the fact that multiple delegations of victims, women’s groups, and ethnic minority representatives met multiple times with the negotiating parties. After listening to the voices of numerous victims and civil society, the negotiating parties integrated their priorities into the agreement.

After the government changed from Santos to Duque, the relationship reverted back to one of mistrust and deprioritization of ethnic minority issues.

The result of these efforts was Chapter 6.2, or the Ethnic Chapter, which safeguards the rights of ethnic minorities transversally throughout the accord by guaranteeing their right to prior, free and informed consent on norms, laws, and plans that affect their communities.

Another victory was the creation of the Special High Instance for Ethnic Peoples (Instancia Especial de Alto Nivel con Pueblos Étnicos), the body ensuring that ethnic minorities have representation and a voice before the commission responsible for verifying the peace agreement is fully implemented.

However, post accords, ethnic communities had to once again fight for inclusion into the implementation planning process. During the special legislative procedure—known as the “fast track” process—which saw the development of an Implementation Framework Plan, ethnic communities were able to get 98 ethnic indicators into the framework for the peace agreement.

A former FARC rebel waves a white peace flag during an act to commemorate the completion of their disarmament process in Buenavista, Colombia, in June 2017 (AP Photo/Fernando Vergara).

While, in theory, all 43 measures that gave constitutional and legal standing to the peace accords in Congress should have gone through a consultation process with both Afro-Colombian and indigenous groups, the reality was different. The government did not use this legislative procedure for all of the projects that would result in national norms. Rather, while the government said it would submit 18 legislative measures in consultation with coalition the Indigenous Permanent Concertation Table (Mesa Permanente de Concertación Nacional, MPC), it only presented six measures and normative projects. Afro-Colombian communities, meanwhile, did not get a chance to go through a formal consultation process.

Despite these early victories, the change in government from Santos to Duque has presented new challenges for ethnic and indigenous communities.

After the Ethnic Chapter was agreed upon, the Santos administration’s relationship with ethnic minorities deepened. It was the Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples who most campaigned in favor of the peace referendum. These interactions opened up a better working relationship between different Colombian authorities—including the Inspector General’s Office and the Human Rights Ombudsman’s office. These two offices are now two of the biggest advocates for the rights of ethnic groups. After the government changed from Santos to Duque, the relationship reverted back to one of mistrust and deprioritization of ethnic minority issues.

All the peace-related projects... require buy-in and leadership from indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities to work.

Problems also arose regarding the Ethnic Chapter, which is critical to the success of the peace accords for a number of reasons.

A new state institution, the Agency for Territorial Renewal (Agencia de Renovacion del Territorio, ART), was created in 2015 in order to bring infrastructure and other state services to rural Colombia. This agency selected 170 municipalities that the government is supposed to prioritize when implementing its rural development initiatives, known as the Development Programs with a Territorial Approach (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDETs).

Within these 170 municipalities are 452 indigenous reserves and 500 cabildos. Furthermore, in those areas, Afrodescendant, raizal and palenquero communities have 307 collective titles and 500 community councils. (It should be noted that the chapter of the peace accords that deals with rural land issues affects areas whereby 51 percent of indigenous and 81 percent of Afro Colombians are concentrated).

The illicit crop substitution program was not designed with any input from ethnic leadership, making communities skeptical of the initiative.

While imperfect, the 300-page peace deal serves as a blueprint for extending civilian authority to areas that, for decades, were controlled by illegal armed groups. But in order to facilitate and guarantee that the state is effective and gains credibility in these areas, it must work hand in hand with the representatives of the ethnic communities. All the peace-related projects—from the PDETs to the illicit drug crop substitution program (Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos de Uso Ilícito, PNIS) meant to counter coca growing—require buy-in and leadership from indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities to work.

Sadly, the government has not complied with the safeguards in the Ethnic Chapter for advancing the legislative measures needed to more fully implement the accord. Neither has it advanced the work of the Special High Instance for Ethnic Peoples.

Residents of Puerto Conto, Chocó, who escaped their village due to fighting between leftist rebels and paramilitaries, disembark at the port of Quibdo in 2002 (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan).

In areas like Chocó, ethnic minorities have participated in the design of PDETs because they value its importance and see these as a mechanism of improving the situation for their people. But the illicit crop substitution program was not designed with any input from ethnic leadership, making communities skeptical of the initiative.

Statements by President Duque and his cabinet have also heightened concerns among ethnic leaders, particularly as it relates to restarting environmentally damaging aerial fumigation of glyphosate while at the same time attempting to implement crop substitution programs. A Constitutional Court decision has stalled fumigations, but leaves room for resumption down the road.

These challenges can be, in part, attributed to a lack of serious political will to advance peace. The government appears to be only interested in meeting UN and OAS measurements widely used to measure success of peace process by academics and the international community.

Essentially, the Colombian government is reducing the agreement to disarmament and integration of fighters, foregoing the structural changes needed to establish a durable stable peace. It appears as though the Colombian government is not looking to address the long term structural problems leading to conflict, nor the ethnic and gender issues.

Reducing the budgets of these rural reform agencies is a direct way of cutting off support to ethnic communities.

Another major issue is that the Colombian government has attempted to fight every effort to allocate funds for the transitional justice system, known as the JEP. The JEP was notified in July that it should expect a budget cut of 30 percent by the Finance Ministry. However, push back from the international community—in particular the UN Security Council—made it politically untenable for the Ivan Duque administration to carry this out.

The final budget for 2020 ended up with a 13 percent increase for transitional justice, with the JEP only increasing its budget by 1 percent, the Truth Commission 18 percent (which, given that the Truth Commission’s budget was initially cut, only meets 56 percent of what they require) and the investigative unit responsible for searching for the disappeared 47 percent. There remains a general deficit of 8 billion pesos for these truth and justice initiatives.

A cursory look at budget allocations for 2019 is instructive in proving the point. The funding for the Agency for Territorial Renewal was also reduced by 63 percent, and the Rural Development Agency’s by 47 percent. These two agencies are essential to meeting the obligations of the rural reform chapter of the peace accord. Reducing the budgets of these rural reform agencies is a direct way of cutting off support to ethnic communities.

In particular, the JEP serves as a voice for the Afro-Colombian and indigenous victims of war crimes committed by the FARC, paramilitaries and the Colombian armed forces. It is the first court in the country’s history to include gender, ethnic, and regional diversity in its makeup, representing a new opportunity for these Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities to access a measure of justice.

Crucially, both the JEP and the Truth Commission underwent a previous consultation process with ethnic minorities in order to incorporate their recommendations so as to guarantee that truth, justice, and reparations integrates the perspectives of their communities. As a result of this, both the JEP and the Truth Commission integrated commissions dedicated to guaranteeing a differentiated response to ethnic minorities within the institutions’ mandates.

Since indigenous communities have their own autonomous juridical systems, coordination between the bodies is required. Beyond this, the aim is to guarantee that the patterns in the violations related to ethnic minority victims and damages caused to these cultures are addressed with mechanisms put in place that guarantee non-repetition of such events. Yet reducing the budget of both the JEP and the Truth Commission limits the impact they could achieve.

Even in situations of relative success, new challenges have arisen in the implementation of Colombia’s peace agreement.

The historic demobilization of around 7,000 FARC combatants successfully decreased violence in the country. It also opened the door for other illegal armed groups to fight for control over the areas they abandoned.

Paradoxically, this scenario has led to a multitude of legal and illegal actors feeling that they are at risk of losing their economic projects and power in those very territories. Since 2016, according to reports by Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsman’s office, the lack of effective protection by the State and high levels of impunity has led to 479 social leaders killed—mainly in places like Cauca, Valle del Cauca, and Choco.

Once in office, Duque was confronted with the reality that completely undoing the accord was not possible.

In fact, according to the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES), in 2018, 56 percent of the social leaders killed in homicides belonged to ethnic groups. A different source, the think tank INDEPAZ, reports that from November, 2016 to July, 2019, 627 social leaders were killed, of whom 142 were indigenous, 55 afro descendant and 245 rural farmers defending the environment or attempting to implement the peace accord’s crop substitution program. Regardless of how you count it, the problem is alarming and poses a significant risk to sustained peace in Colombia.

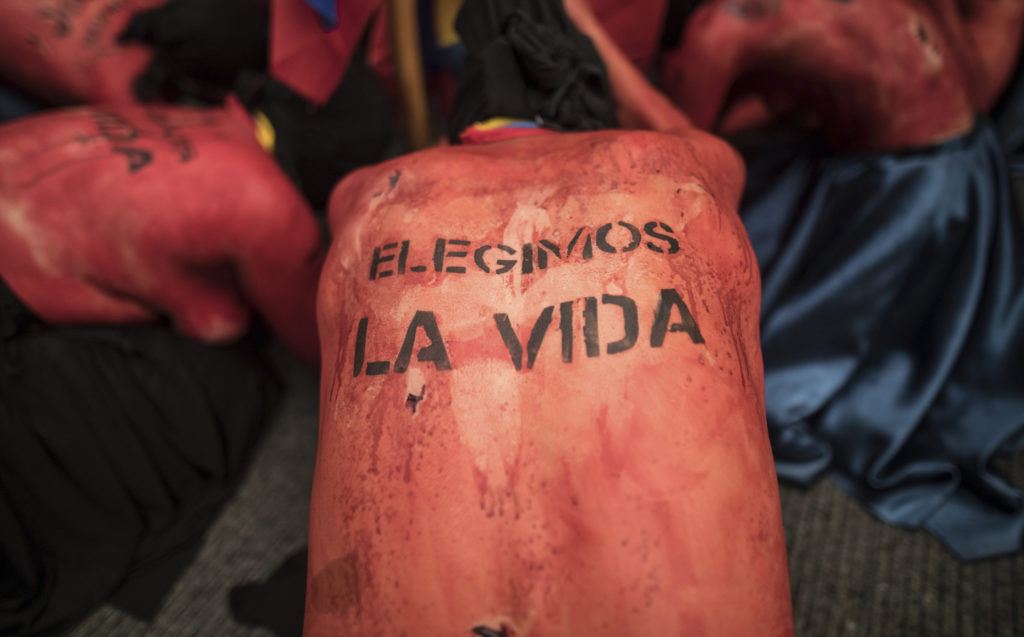

Women perform during march against the murders of activists, in Bogota, Colombia, Friday, July 26, 2019. Colombians took to the streets to call for an end to a wave of killings of leftist activists in the wake of the nation’s peace deal (AP Photo/Ivan Valencia).

The security crisis is particularly acute in the Pacific region where Afro-Colombian and indigenous are experiencing new displacements and acute humanitarian crises. The state could very well detain much of this violence if it advanced the Commission for National Security Guarantees—an initiative set up in the peace agreement, meant to dismantle illegal armed groups. Furthermore, by advancing the obligations in the FARC accord, the government would send signals to the active guerrilla movement and the National Liberation Army (ELN) that it keeps its word in negotiations.

Compounding the situation, Colombia’s politically polarized climate led to the peace agreement being rejected in a subsequent referendum. Resistance from the entrenched political and economic elites to accept the terms of the peace deal paved the way for the election of right-wing Ivan Duque as president, who campaigned on the promise of making changes to the accord to appease their concerns.

By starving key aspects of the accord of resources and trying to limit the work of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, Duque is deferring to powerful interest groups who have rarely acted with the interests of vulnerable ethnic communities in mind.

Once in office, Duque was confronted with the reality that completely undoing the accord was not possible. A constitutional infrastructure was already in place and the international community had placed all its bets on peace.

In response, President Duque unsuccessfully attempted to remand crucial legislation required to establish the transitional justice system. He has proposed changes that would alter six of the 159 provisions of the peace deal legislation. A major sticking point for Duque and his supporters concerning the JEP is that the FARC rebels and the Colombian armed forces are not judged in the same manner for war crimes. By attempting to change the established provisions, the president all but assures that perpetrators of grave human rights crimes will lose any incentive to participate in the truth-telling process.

This could impact cases that the JEP has already advanced. According to the JEP’s latest report, 9,706 FARC ex-combatants and 2,156 members of the Colombian armed forces have agreed to testify before the tribunal. The political efforts to change and diminish the transitional justice infrastructure means that these cases could plunge into uncertainty.

The leaked internal documents from the Colombian armed forces revealed by the New York Times point to the military resorting to perverse tactics to gain military advantages and boost their death toll. The risk of peace crumbling and the cycle of war repeating itself in Colombia is high unless the country advances the transitional justice provisions of the accord, and in that way revealing the full truth of the past.

By starving key aspects of the accord of resources and trying to limit the work of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, Duque is deferring to powerful interest groups who have rarely acted with the interests of vulnerable ethnic communities in mind. That said, the mechanisms to turn all of this around are there—what it requires is the political will of the government to work with ethnic minorities to advance the country forward.