(AP Photo/Sandra Sebastian)

(AP Photo/Sandra Sebastian)

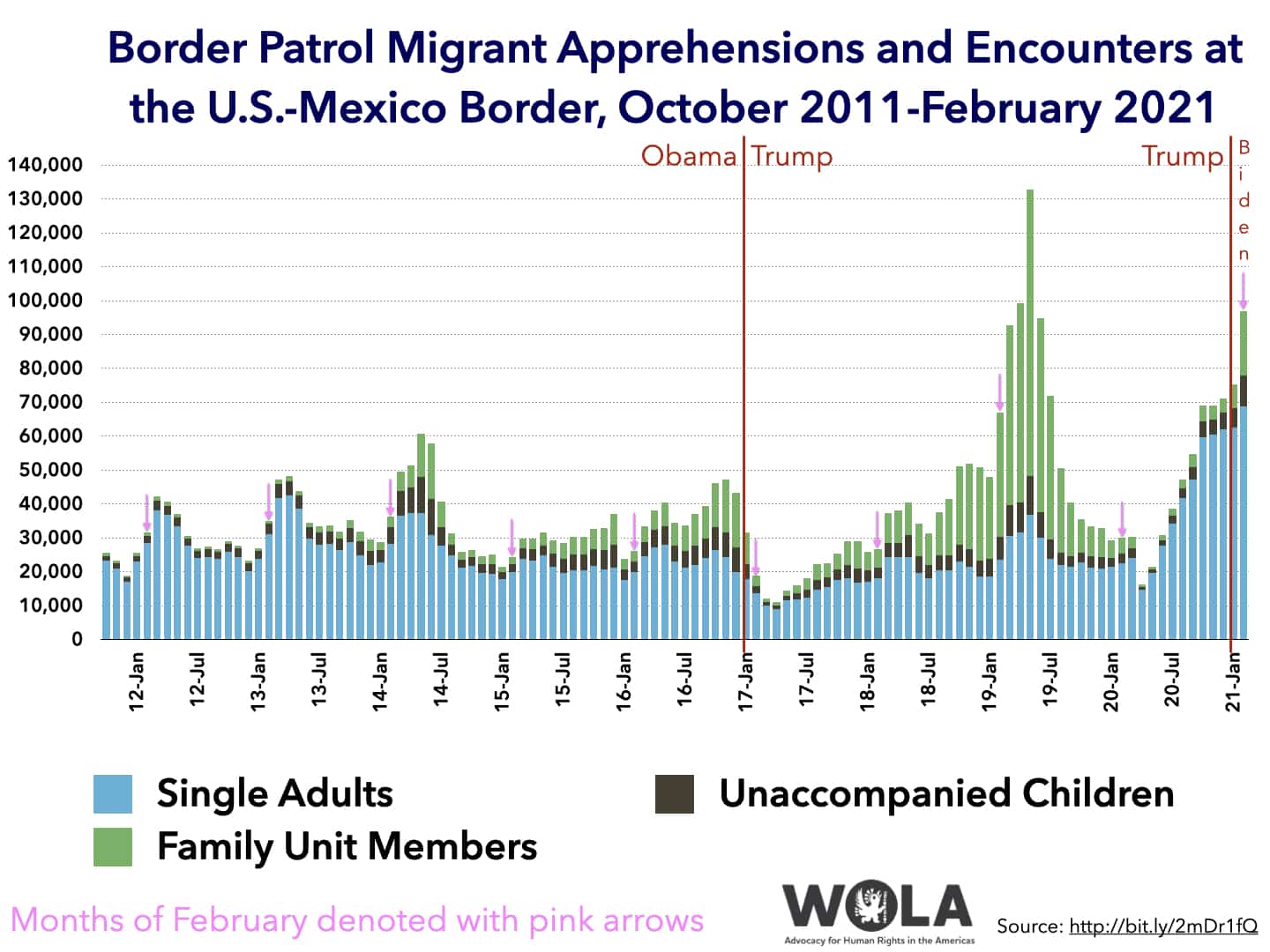

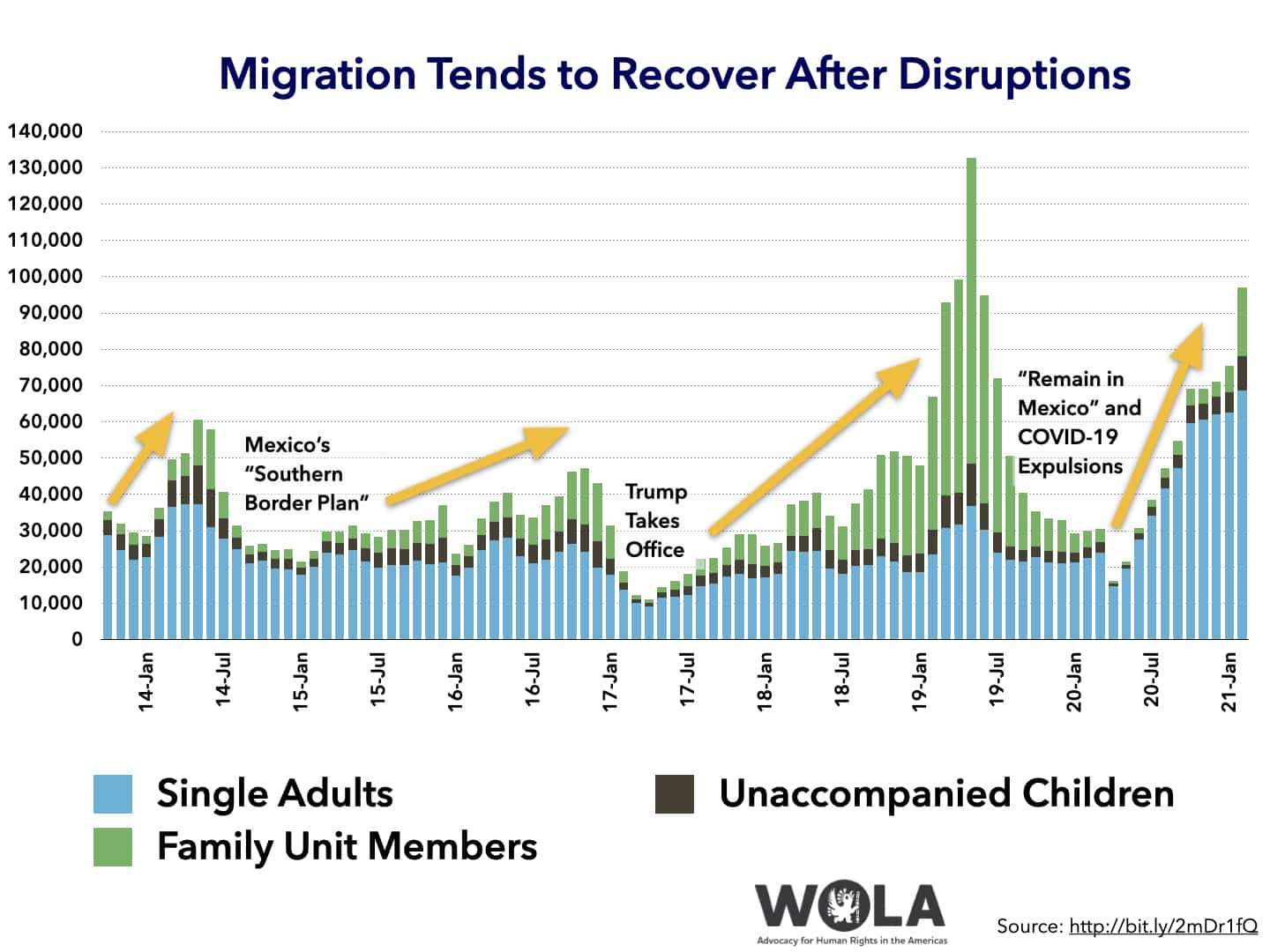

It may seem ironic, but even as it carried out the cruelest anti-migration policies in decades, the Trump administration presided over the largest flows of migration at the U.S.-Mexico border since the mid-2000s.

This continued through Donald Trump’s last months in office, which saw migration rise sharply even as stringent pandemic measures made the pursuit of asylum impossible. This shows the futility of declaring war on asylum, and the inevitability of large migration flows at a time of overlapping security, economic, political, public health, and climate crises.

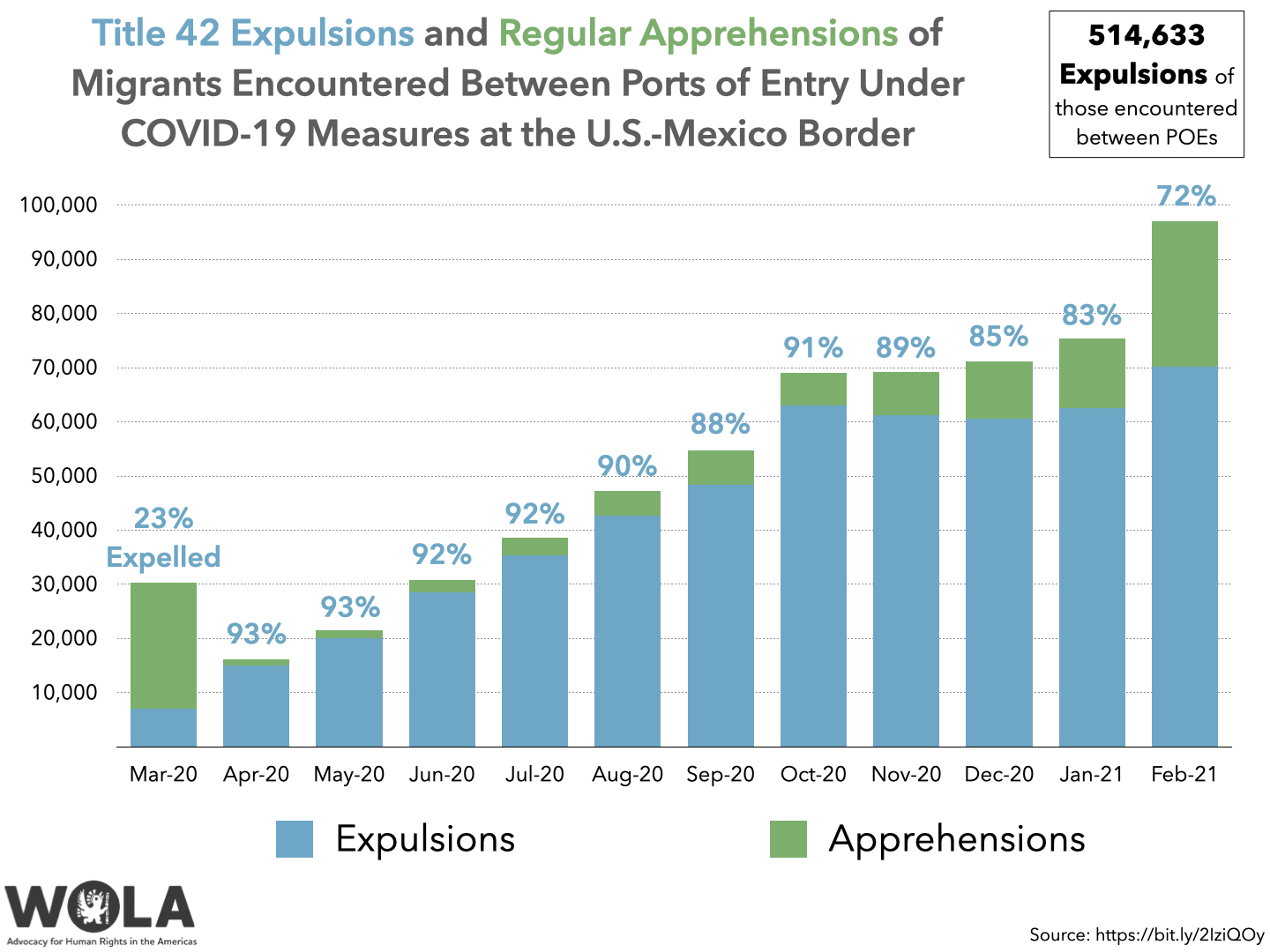

The jump in migration of Trump’s final months continued accelerating during Joe Biden’s first two months in office. This is happening even as Biden’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) keeps in place “Title 42,” a probably illegal Trump-era pandemic provision that expels most migrants within hours, regardless of their protection needs.

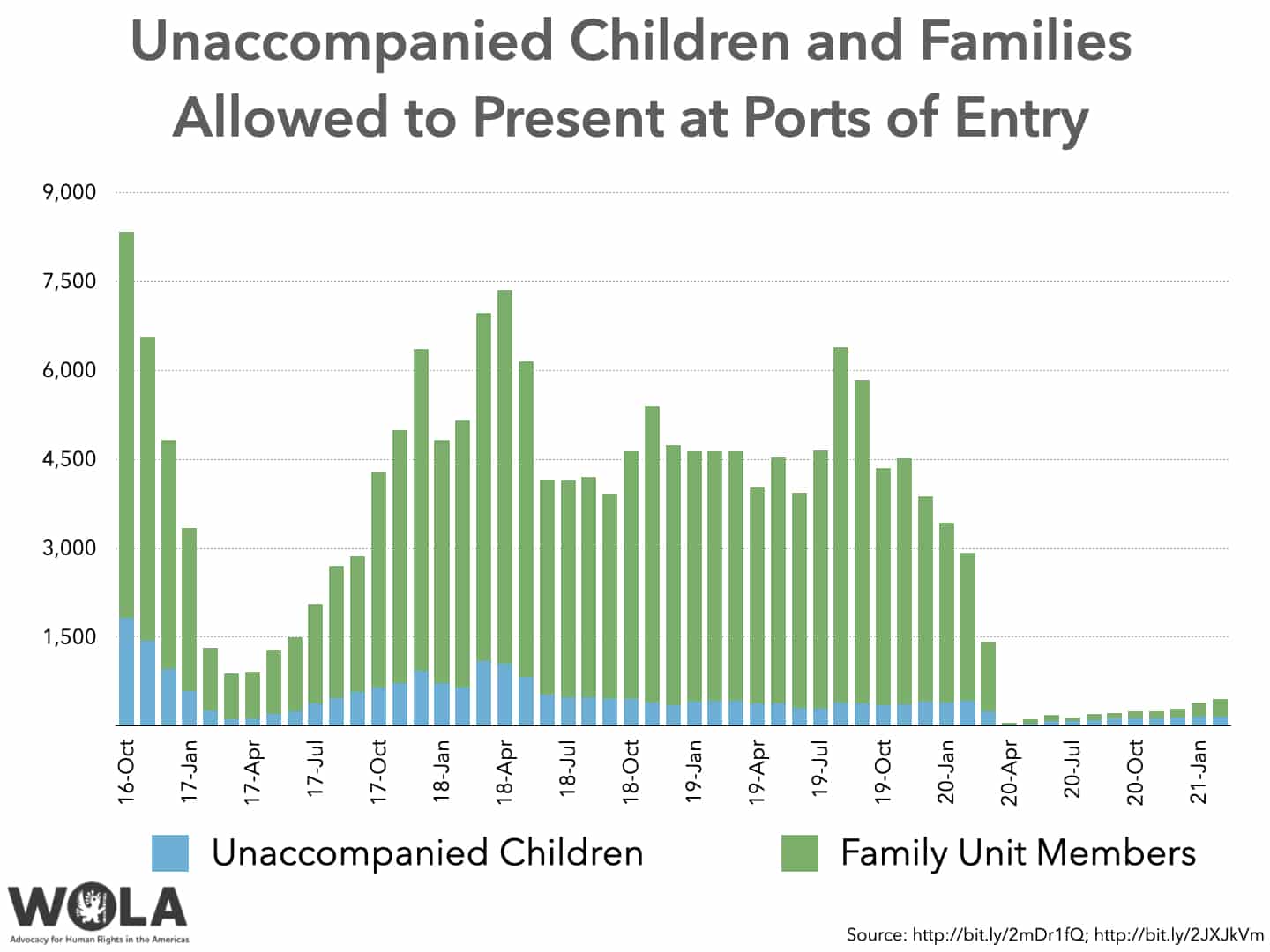

The increased numbers of people crossing the border right now are something that border experts have predicted for some time now. The roots of what is happening are in the Trump administration policies that caused massive numbers of people to be stuck on the Mexican side of the border—policies like “Remain in Mexico” (which forced over 70,000 asylum seekers to wait for their U.S. court dates in Mexico border cities) and “metering,” a practice under which U.S. border authorities place severe limits on who is allowed to approach ports of entry and ask for asylum, in violation of U.S. and international law.

The increased border crossings were predictable, not because of Biden administration policies like winding down “Remain with Mexico,” but because of the dangers put in place by Trump’s cruel and illegal policies of deterrence.

Of the 114 months since October 2011 for which WOLA has detailed monthly data, February 2021 saw the third-most Border Patrol encounters with migrants. (The actual number of people was probably much lower since, as noted below, many migrants expelled under Title 42 attempt to re-enter shortly afterward.)

While third-most sounds like a lot, the impact on border authorities’ workload is minimal because Title 42 persists. Of the 96,974 migrants whom Border Patrol “encountered” in February, it quickly expelled 72 percent—down only slightly from the end of the Trump administration, which expelled 85 percent in December and 83 percent in January. The remainder whom Border Patrol actually had to process last month—26,791 migrants—was the 77th most out of the past 114 months. Being in 77th place hardly constitutes a crisis.

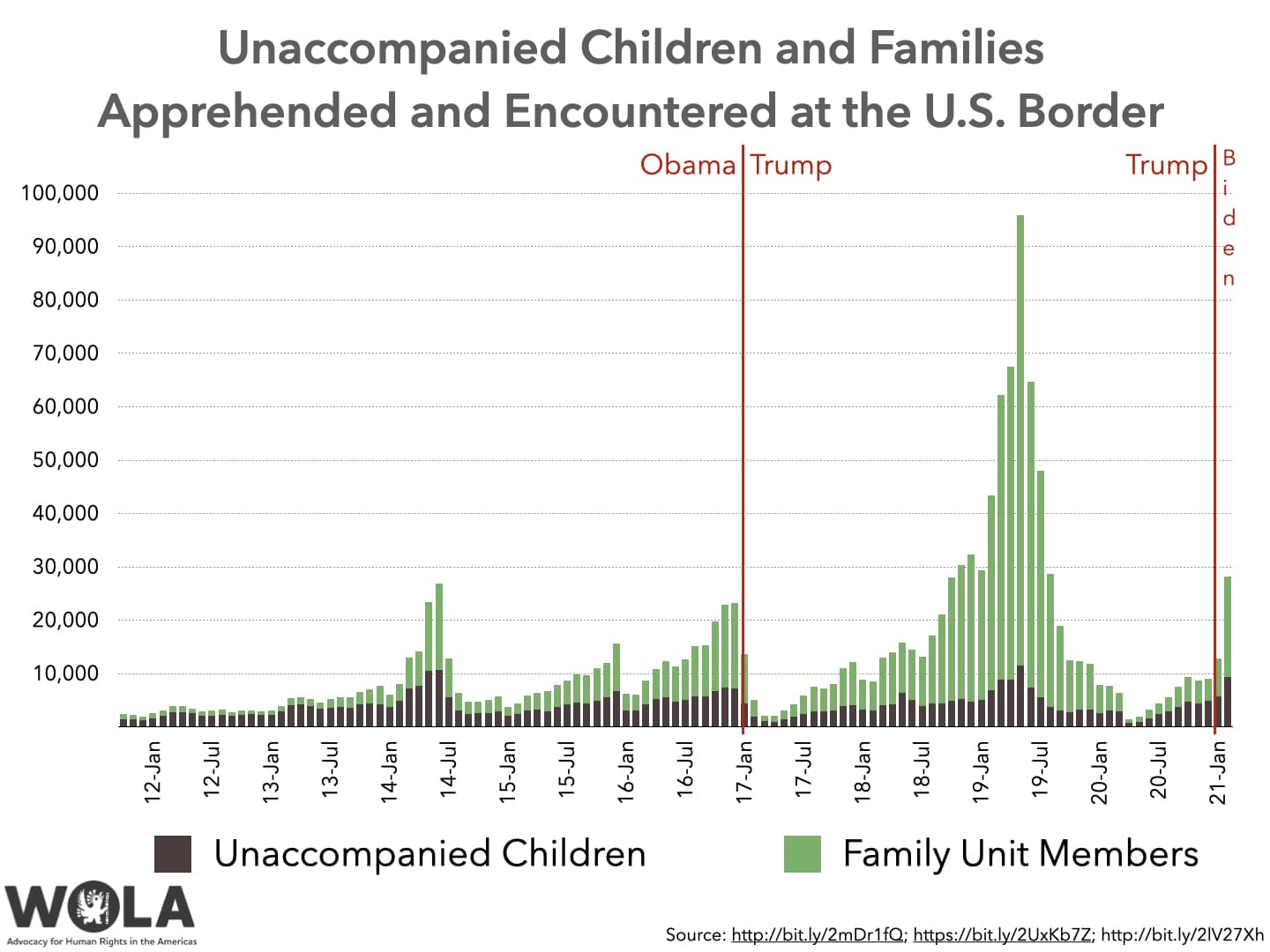

There is a serious capacity issue right now, though, for one especially vulnerable category of migrant: children who arrive unaccompanied by a parent or guardian.

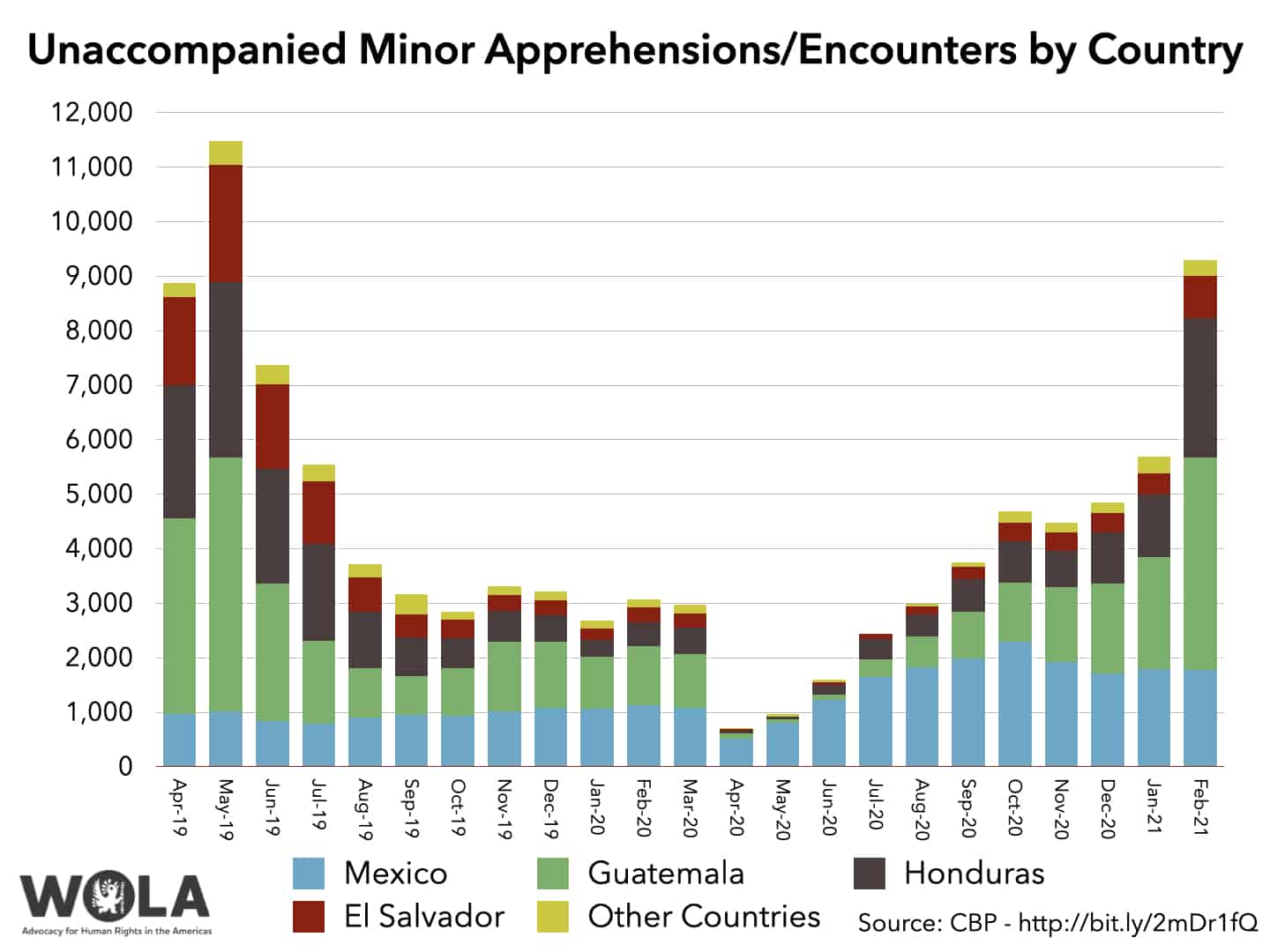

In February, Border Patrol apprehended 9,297 unaccompanied children, the most since May 2019. To put it another way, in terms of apprehensions at the border, February was the fourth-largest month for unaccompanied kids in the last 114 months for which we have data—possibly ever. Arrivals of unaccompanied children continue to increase, averaging 400 per day so far in March.

Unaccompanied children are the only migrant population that the Biden administration is refusing to expel. (The Trump administration was using Title 42 to expel them until a judge stopped the practice in November. While that judge got overruled on appeal in late January, the incoming Biden administration refused to expel vulnerable children alone back to their countries.)

42 percent of February’s unaccompanied child arrivals were from Guatemala, 28 percent from Honduras, 19 percent from Mexico, 8 percent from El Salvador, and 3 percent from other countries.

It is quite possible that 2021 will be a record-breaking year for unaccompanied children crossing the border. The Biden administration had previously predicted that up to 117,000 unaccompanied migrant children could cross the border in the 2021 fiscal year (breaking the previous record of 76,020 children in 2019).

This has challenged the capacities of U.S. agencies assigned to care for them, generating headlines about a “crisis.”

Here is how the U.S. government is supposed to care for unaccompanied children, according to the 2008 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act:

Right now, the bottleneck is (2) above: ORR is running out of state-licensed shelter space, which was reduced by COVID-19 precautions. As a result, thousands of children have been stuck for many days in (1): grossly inadequate Border Patrol station holding cells.

The Biden administration is rushing to provide emergency shelter capacity for the overflow of children, enlisting the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to open up temporary shelters: a tent facility in Carrizo Springs, Texas; a convention center in Dallas; and other sites in Homestead, Florida; Mountain View, California; Fort Lee, Virginia; and possibly elsewhere.

Emergency shelters are hardly appropriate for unaccompanied children, and WOLA expects that a more established Biden administration will be better prepared for future increases of unaccompanied child migration. For now, though, these facilities are the “least bad” choice.

Once this temporary system is in place and U.S. agencies’ bottlenecks ease, it’s likely that alarmed coverage of a “border crisis,” and accompanying political posturing, will calm. Once that happens, WOLA hopes that the Biden administration will turn its attention to the real crisis at the border: the near-impossibility of receiving protection in the United States.

Because Title 42 is still in place, migrants at the border are being swiftly expelled back to Mexico if they are from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. In Texas, for instance, that usually means just being captured in the field and left at the middle of a border bridge over the Rio Grande, without ever seeing the inside of a Border Patrol station.

These expulsions are creating a cycle: people of primarily Mexican and Central American origin cross the border, are expelled, then many try again. The “recidivism rate”—the percentage of apprehended migrants who had been apprehended before, expelled, and tried to cross again—was 38 percent in January, up from 7 percent in 2019. Others who cross, including thousands of Haitians, are being flown back to their own countries, regardless of the risks they may face.

As indicated by CBP’s February 2021 numbers, we’re seeing an expected rise in border apprehensions. (Again, we were already seeing this happening prior to Election Day November 2020, despite the Title 42 expulsions policy).

We have seen this before in the past eight years. A crackdown on migration reduces the flow of people at the U.S.-Mexico border for a time. But as long as root causes remain unaddressed and the U.S. asylum system remains mired in backlogs and dysfunction, the numbers always recover.

The rise in migrants crossing the border will continue to increase this spring, regardless of the Biden administration’s gradual expansion of its capacity to process asylum seekers seeking protection in the United States. Persistent violence, a pandemic economic collapse, and historically severe hurricanes have created an acute need to migrate to seek protection and economic survival. In the face of this, the Biden administration’s responsibility is to manage these increased migration flows in an orderly, rights-respecting way, upholding the dignity of people forced to flee.

Currently, however, only a miniscule number of people are allowed to present themselves at a port of entry to petition for asylum there. Apart from the first-phase system put in place to admit asylum seekers previously under the “Remain in Mexico” program, there is no orderly way to seek protection in the United States right now. This leads many people fleeing harm to seek to cross the border without inspection.

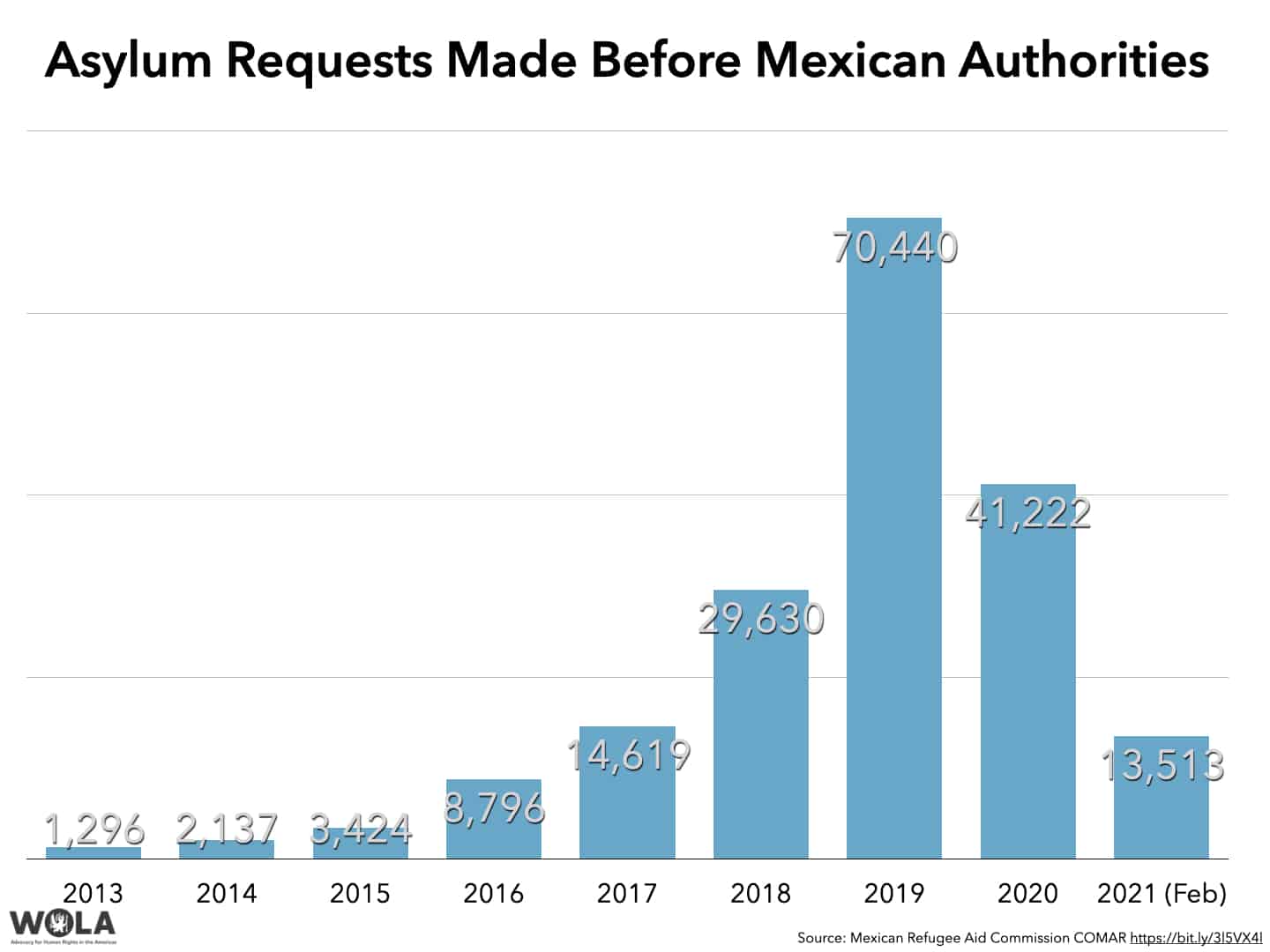

The increased need for protection in the Western Hemisphere isn’t a phenomenon that’s limited to the U.S.-Mexico border. Mexico’s asylum agency, COMAR, has processed 13,513 asylum requests so far this year. If this pace keeps up, Mexico will break its previous 2019 record for asylum requests. Costa Rica is a destination for tens of thousands of protection-seeking migrants from Nicaragua, Cuba, Venezuela, and elsewhere in Central America. And several South American countries have taken in fleeing Venezuelans.

What we’re seeing at the border is a mixed flow of people—those fleeing crippling poverty and the devastation of two hurricanes, as well as those who, because of persistent violence and political turmoil, urgently need protection. What’s needed at the border is recognition that asylum seekers have an enshrined right to protection—and those protection needs should be met, not blocked or shunted off to other countries.

What’s also needed is recognition that climate change disasters and the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to fuel migration in the region—creating the need to offer additional labor opportunities (such as temporary visa programs for Central Americans already in the United States, for example). The U.S. government is capable of meeting these challenges in an orderly, rights-respecting way (see the section below for recommendations on what needs to happen in the short and medium-term to address what’s happening at the border).

In February, most children apprehended originate from Guatemala and Honduras, two countries still reeling from the impact of two record-breaking hurricanes in the fall, economic inequalities worsened by COVID-19, and persistent violence.

What’s behind this increase? The backlog of asylum seekers—a humanitarian disaster created by the Trump administration—who have been waiting, in some cases for years, at the U.S.-Mexico border. At the moment, unaccompanied children (apart from unaccompanied Mexican children) are the only population that stand a 100 percent chance of being released into the United States to start an asylum process while living with relatives. (Families seem to have stood about a 40 percent chance in February.)

In terms of the big picture, this is the fourth time that we’ve seen a significant increase in unaccompanied child and child-and-family migration at the U.S.-Mexico border since 2014. What these numbers confirm is that the population of people arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border has changed.

Right now, we have a militarized “border defense” system, hardly ideal even to interact with the typical border crosser of the 1990s and 2000s—a single adult male. But since the mid-2010s, at least a third of the population coming to the U.S.-Mexico border aren’t looking to cross undetected: they are children and families actively seeking out U.S. authorities to ask for protection, or unaccompanied children seeking to be reunited with family already in the United States. Notably, in 2019, well over half of the people apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border were children and families.

The Biden administration’s major challenge at the border is to adjust to this shift and adopt policies that address the reality of child-and-family migration. Civil society groups at the border have been sounding the alarm about this for years now—the U.S. government hasn’t yet fully listened. (And under the Trump administration, the United States lost four years focusing on cruel and ineffective deterrence policies, instead of spending that time adapting to this new reality).

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) needs to build up its capacity to process asylum seekers. No one should have to feel like their only fair shot at entering the asylum process is to climb walls or risk drowning in the Rio Grande. There should be no need for asylum seekers to seek out smugglers to cross the border—they should be able to show up to a designated location and go through an administrative process.

This doesn’t mean that DHS needs to build up its ability to process asylum seekers at the ports themselves, where facilities are often small and crowded. While taking steps to preserve public health, protection-seeking migrants should be bused to nearby facilities manned largely by civilian personnel trained in working with populations that have suffered trauma—not armed, uniformed law enforcement agents.

DHS is currently building and repurposing facilities, and hiring staff, to build up its capacity to address the rise in protecting-seeking migrants. Still, more needs to be done, and much more quickly. Further, the U.S. government needs to build permanent infrastructure so that we’re no longer opening and closing temporary “influx facilities” at the border every few years, every time there is a new increase in border crossings.

While the Biden administration has taken several major steps to restore asylum access, missing from the policy rollout are timelines for ending several Trump-era practices that closed the U.S. asylum system. Clear timelines are crucial to maximize governmental, international, and civil society stakeholders’ ability to make informed decisions and to prepare for their roles in the process.

While asylum seekers themselves don’t have the luxury of choosing when to flee their countries, knowing when they can be admitted is essential for those waiting in Mexico so that they can plan their border arrival (to the extent possible) and know that they will in fact have the chance to pursue or renew asylum claims or that their slot on a waitlist will be respected.

In the absence of such clarity and amid an array of disinformation targeting this community, asylum seekers may be deceived by smugglers who offer false versions of U.S. plans, or may attempt to enter without inspection between points of entry, increasing risks to their lives and well-being.

What are the timeframes missing from the major Biden-era migration and asylum policies announced so far? First, there is a need for calendarized plans for processing “Remain in Mexico” asylum seekers.

The Biden administration has taken the first steps in winding down this Trump-era policy—phase one applied to about 25,000 people—those with active cases in the program (perversely called the “Migration Protection Protocols,” or MPP, by the Trump administration). We still don’t know what those who weren’t admissible under this first phase should expect.

Nor are there clear timeframes in place for those who were prevented from seeking asylum in a timely fashion due to CBP “metering” (the practice of only receiving a certain number of asylum claims per day). The University of Texas’s Strauss Center documented approximately 16,250 asylum seekers on “metering” waitlists in nine Mexican border cities in February 2021.

Stakeholders also continue to await time-bound plans to end Title 42 expulsions, under which the vast majority of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, including potential asylum seekers, are swiftly expelled.

Plans to reinstate the Central American Minors program also require a clear calendar. The U.S. government created this program to allow certain children in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala to come directly to the United States to reunite with U.S.-based parents, thereby avoiding the dangerous journey through Mexico. The Trump administration terminated the program in 2017, but the Biden administration recently announced a two-phase plan to reopen it, starting with approximately 3,000 cases of eligible applications that were closed when the program was ended.

In a positive step, the announcement indicates that eligible parents will be contacted starting in mid-March; the timeline from there remains pending. Clear information in this regard will help to spare eligible Central American children from exposure to violence in Mexico and allow them to reunite safely with their family members. The administration also needs to develop its plans to expand the program to address its multiple shortcomings including broadening eligibility criteria, improved and quicker processing, and access to legal counsel.

While Costa Rica, Panama, and other countries have seen substantial arrivals of people in need of protection, given its location, size, and capacity, Mexico undeniably has a crucial role to play in responding to the regional refugee crisis. Asylum requests in Mexico increased by more than 700 percent between 2016 and 2019. More than 125,000 people have requested protection in Mexico since President López Obrador took office in December 2018, including over 13,500 in the first two months of 2021. While Mexico has improved its reception and processing capacity, further budget and staffing increases are needed to enable Mexico’s refugee agency, COMAR, to respond to current levels of demand.

Asylum seekers also continue to face significant obstacles to accessing protection in Mexico. These include a 30-day time limit to request asylum after entering the country, the requirement to stay in the state where the asylum request was made while it is being processed, inadequate access to a humanitarian visa that would facilitate access to basic services, and long delays in resolving claims.

Additionally, since asylum seekers are frequently held in detention while their cases are processed, poor conditions in detention centers drive many of them to drop their claims in order to be released. A program to provide alternatives to detention, started in 2016, is not being fully implemented by Mexico’s national immigration agency, the INM. Another issue is that many migrants who are detained by the INM are not adequately informed of their right to seek protection in Mexico in the first place; others are denied entry upon arrival at Mexican airports. Addressing these problems is crucial if Mexico is to ensure access to asylum within its borders.

Certain basic administrative actions would greatly facilitate asylum seekers’ ability to make claims. One of these would be to allocate resources so that COMAR can establish a regular presence at Mexico’s southern border. Currently, asylum seekers presenting a claim at the border will generally be detained for at least a few days by the INM. To avoid detention, many asylum seekers try to travel undetected to towns close to the border to present themselves at a COMAR office or shelter. On this journey they are often victims of crimes including kidnapping, sexual assault, and robbery.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has dramatically expanded its presence in Mexico in recent years and provided important technical and infrastructure support to COMAR. Apart from assisting COMAR, the UNHCR supports the construction of shelters for asylum seekers and refugees, provides assistance to civil society organizations serving asylum seekers, and directly supports asylum seekers waiting for their claims to be processed. The United States is the largest donor for UNHCR in Mexico, providing an estimated $42 million in assistance in 2020.

Apart from appropriating additional financial support, the U.S. government should consider developing procedures with the Mexican government to provide access to protection in the United States for individuals who would face persecution in Mexico, as well as unaccompanied children when the best interest determination is that they should be united with their U.S.-based family members.