(AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

(AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

Semana, a Colombian newsmagazine that often exposes human rights wrongdoing in Colombia’s armed forces, published another scoop on May 1, 2020. Army intelligence units, it found, had been developing detailed dossiers on the personal lives of at least 130 reporters, human rights defenders, politicians, judges, and possible military whistleblowers. The list of targets includes U.S. citizens who work in Colombia as reporters for major media outlets.

Semana has a long record of revealing malfeasance in the security forces. The last five covers are from the past twelve months.

This is the latest of a long series of scandals involving illegal wiretapping, hacking, surveillance, or threats from Colombia’s powerful, U.S.-backed security and intelligence forces. Though Colombia has taken modest steps toward accountability over its military, the Semana revelations show us how fragile and reversible this progress is.

The purpose of intelligence should be to foresee and help prevent threats to law-abiding people and their freedoms. In a country where a social leader is murdered every other day, such threats abound. For scarce intelligence resources to be diverted away from those threats, and channeled instead to illegal and politicized ends, is a betrayal of public trust and an attack on Colombian democracy.

Preventing a further repetition of these intelligence abuses will require Colombia’s government to take bold steps. These include holding those responsible, at the highest levels, swiftly and transparently accountable for their crimes. Because U.S. assistance may be implicated in, or at least adjacent to, the military intelligence units’ actions, how Colombia responds must have giant implications for the integrity of the bilateral relationship and the ostensible purposes of U.S. aid. Any indication that these crimes may once again end up in impunity must trigger a cutoff of U.S. aid to the units involved.

What we know about the latest revelations comes mainly from Semana and other Colombian media. We lay it out in the following narrative.

Unauthorized wiretapping scandals recur with numbing regularity in Colombia. In 2009, Semana—which tends to reveal most of these misdeeds—uncovered massive surveillance and threats against opposition politicians, judicial personnel, reporters, and human rights defenders. These were carried out by an intelligence body, the Administrative Security Department (DAS), that reported directly to President Álvaro Uribe. The DAS had already run into trouble earlier in Uribe’s government (2002-2010) for collaborating with paramilitary groups on selective killings. As a result of the 2009 scandal, the DAS was abolished in 2011.

In 2013 Colombia passed a landmark intelligence law prohibiting warrantless surveillance or intercepts, and put strong limits on judges issuing warrants against people who were not organized criminals, drug traffickers, or terrorists. The law created a congressional oversight body that has been largely inactive, while a commission to purge intelligence files issued a report that was not acted upon.

By 2014, army intelligence was at it again. Semana revealed the existence of a hacking operation, “Andromeda,” working out of what looked like a restaurant in western Bogotá. Its targets included government negotiators participating at the time in peace talks with the FARC guerrillas. Since then, efforts to hold accountable those responsible for Operation Andromeda have shown “no results to date,” according to the Inter-American Human Rights Commission.

President Juan Manuel Santos’s second term (2014-2018), marked by the conclusion of a peace accord with the FARC, was a quieter period for military human rights scandals. A moderate, and moderately reformist, high command implemented doctrinal changes and supported the peace process, while human rights groups documented fewer extrajudicial executions committed directly by the armed forces.

Progress reversed sharply in 2019. The high command that new President Iván Duque put into place, including Army Chief Gen. Nicacio Martínez, fell under criticism from human rights groups for their past proximity to “false positive” extrajudicial killings a decade earlier. Colombian media began gathering reports about increased abuses, and abusive behavior, at the hands of military personnel. Semana revealed that in a January meeting Gen. Diego Luis Villegas, the chief of the military’s “Vulcan Task Force” and now head of the army’s “Transformations Command,” said, “The army of speaking English, of protocols, of human rights is over.… If we need to carry out hits, we’ll be hitmen, and if the problem is money, then there’s money for that.”

President Iván Duque and Army Chief Gen. Nicacio Martínez, February 4, 2019 (Image c/o the Colombian presidency).

In April, troops in Gen. Villegas’s task force killed a former FARC guerrilla in northeast Colombia’s volatile Catatumbo region. Semana reported later in the year that a colonel had told his subordinates that he wanted Dimar Torres dead. (Gen. Villegas apologized publicly for the killing, and the colonel is detained awaiting trial.)

In May 2019, the New York Times ran with a story that Semana had been sitting on: army chief Gen. Martínez and his commanders were reviving “body counts” as a principal measure of commanders’ effectiveness. Rather than measure territorial security or governance, army brass decided to require unit commanders to sign forms committing themselves to a doubling of “afectaciones”—armed-group members killed or captured—in their areas of operations. This raised concerns about creating incentives for “false positives”: killings of innocent civilians in order to pass them off as combatants to pad body counts, as happened thousands of times in the 2000s.

Whistleblowers within the military were the main sources for the Times story. Rather than upholding those whistleblowers and rethinking “body counts,” the high command launched a campaign to root out officers who talked to the media, including New York Times reporter Nicholas Casey. In what Semana revealed in July and called “Operación Silencio,” counterintelligence officers began interrogating and polygraphing army colleagues suspected of snitching. (We would learn in May 2020 what the army was doing at the time about Nicholas Casey.)

The second half of 2019 had more bumps for the army. Semana revealed corruption scandals, including selling permits to carry weapons and misuse of funds meant for fuel and other needs. These led to the firing of five army generals, including Gen. Martínez’s second in command. In November, the civilian defense minister, Guillermo Botero, was forced to resign amid allegations of a cover-up of an August bombing raid on a rearmed FARC dissident encampment, which killed eight children.

After a stormy year-long tenure, Gen. Nicacio Martínez, the army commander, abruptly resigned on December 26, 2019. (The General told El Tiempo that he discussed his exit with his family on December 8, notified President Iván Duque the next day, and was out 17 days later.) On January 13, 2020, Semana published a bombshell cover story on what it called “the real reasons that caused the government to retire the army commander.”

The magazine revealed that during much of 2019, army intelligence had been illegally intercepting the communications of Supreme Court justices, opposition-party politicians, journalists, and others. They used a piece of malware called “Invisible Man” and two small hardware devices called “StingRays” to intercept phone calls, text messages, and other data.

A StingRay device (Image from U.S. Patent and Trademark Office c/o The Intercept).

The units involved included the Army Cyber Intelligence Battalion (Bacib), at an army communications facility in Facatativá, a town west of Bogotá; and the army’s Information Security Counterintelligence Battalion (Bacsi), at the CATAM airbase next to Bogotá’s airport. Both are part of the army’s Military Intelligence Support Command (Caimi) and Military Counterintelligence Support Command (Cacim).

Again, Semana’s key sources for its scoop came from within the army. Officers who objected to the operation, uncomfortable with the direction that Gen. Martínez and other commanders were taking the institution, blew the whistle again.

“Some army units have been dedicated in the past year to deploying their mobile units and using their latest-generation equipment to know the activities of some reporters, politicians, judges, and even colonels, generals, and commanders of other forces,” a military source told Semana. A source said that the intelligence officers shared intercepted information with “an important politician” in President Iván Duque’s governing party. This individual remains unidentified, though Semana stated that it is not Senator Álvaro Uribe, who was president of Colombia during the 2009 DAS intercept scandal.

Victims of the 2019 intercepts included:

For three months in late 2019, Semana reported, army chief Gen. Martínez ordered two StingRay devices lent to two colonels, one active and one retired. “We know that they were used for political activities,” a military source told the magazine, noting that the devices were erased when returned.

During the second half of 2019, including the months that the StingRays were employed, reporters from Semana magazine and their military sources came under a heavy-handed campaign of death threats and conspicuous following. They and their relatives began receiving funeral prayer cards (sufragios, with messages like “rest in the peace of the Lord”) as a not-so-subtle form of death threat. One even went to a lead reporter’s six-year-old niece.

The tombstone left on journalist Calderón’s car, and funeral prayers left as threats (Image c/o Semana).

“I don’t know how many sufragios I’ve received,” Ricardo Calderón, Semana’s chief investigator on the case, told Spain’s El País. One day in 2019 Calderón even found a marble tombstone, with his birthdate and an August 7, 2019 date of death, tucked behind the spare tire of his parked SUV. Security cameras and cellphone tracing revealed that the individual who left the tombstone drove his vehicle to an army counterintelligence facility. Army personnel confirmed to Calderón that the vehicle was registered to the army.

In September, Calderón learned that some military personnel were seeking to hire hitmen to kill him. The threats forced him to leave Colombia for a few weeks, but he returned.

Though she did not realize she was one of the army’s surveillance targets, Judge Lombana led a raid of the Army Cyber Intelligence Battalion (Bacib) installations in Facatativá, in order to investigate a complaint of illegal surveillance. The operation took place on December 18, 2019, days after Gen. Martínez told President Duque of his intention to resign. In an operation that Semana called “like something from a movie,” Supreme Court investigators sought to collect computers, memory cards, and cellphones while army personnel worked frantically to remove hard drives and pass devices out of windows to colleagues. Investigators found one individual hiding behind a file cabinet with a computer.

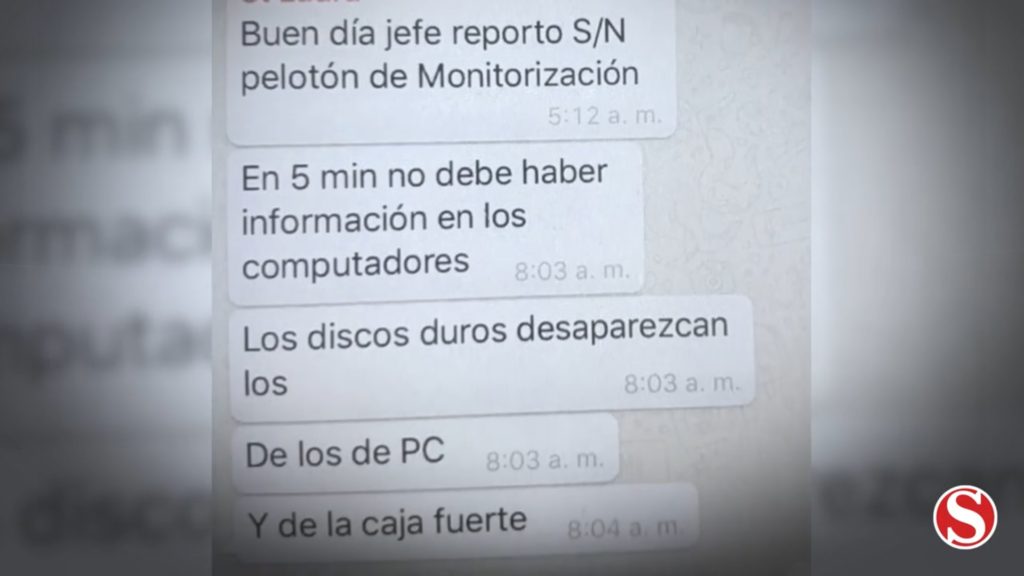

During the December judicial raid, military intelligence personnel WhatsApped instructions to clear out evidence. (Image c/o Semana video)

Gen. Nicacio Martínez denied any knowledge of the activities detailed in Semana’s January 2020 article, and disputed the magazine’s claim that it had anything to do with his sudden and premature resignation. He told El Tiempo that the allegations were “retaliation” against him “for denouncing and preventing acts of corruption within the army.” Gen. Martínez cited “strong economic interests” arrayed against him, without offering any specifics.

Nearly four months passed, during which Colombian authorities announced no progress or results in their investigations of the wiretaps, intercepts, and threats. Gen. Martínez’s replacement at the head of the army, Gen. Eduardo Zapateiro, “tried to fire some of those involved,” La Silla Vacía reported, “but according to one source who has reasons to know about it, Armed Forces Commander Gen. Luis Fernando Navarro preferred simply to transfer them to other posts while the scandal cooled. ‘They know too much’ was the source’s explanation.”

There was a curious episode, meanwhile, on March 10, 2020. On its Twitter account, the army briefly created a list of accounts called “Opposition.” About 33 journalists, former guerrillas, politicians, opinion leaders, and non-governmental advocates received a Twitter notice reading, essentially, “Army of Colombia has added you to its ‘opponents’ list.” The army apologized and deleted the list—or perhaps took it private.

From the Twitter account of the online investigative media outlet Cuestión Pública (@cuestion_p), which was added to the army’s “opposition” Twitter list.

The January Semana piece had mentioned “folders on hard drives and USB memory sticks” with information taken from “public entities, NGOs, and media outlets. It added, “there are folders storing information about officials at the DIAN [taxation authority], lawyers’ collectives, and human rights defenders, among others.” On May 1, the magazine added a giant new layer of detail to this finding.

“The army carried out a program of data surveillance in which the majority of its targets were journalists, several of them American,” reads Semana’s latest cover story. “Politicians, generals, NGOs, and union leaders are part of the list of more than 130 victims.” During Gen. Martínez’s tenure, between February and early December 2019, the army compiled dossiers on the work, relationships, and social lives of people who could hardly be described as national security threats.

These appear to have relied less on hacking tools like “Invisible Man” and “StingRays,” and more on a thorough scraping of open-source information available on the internet and on social media, including geo-referencing data. According to El Espectador, about two years ago the army purchased a software tool called Voyager, sold by an Israeli firm, that “uses artificial intelligence to analyze an otherwise indecipherable amount of data and predict human behavior.”

The dossiers included elaborate diagrams of their targets’ social networks and contacts, including phone numbers, addresses, email accounts, friends, relatives, colleagues, traffic infractions, and even their assigned voting places. They made note of the individuals with whom the targets interacted most on social media, including “likes” of posts and tweets.

One of the first and most thoroughly documented targets was Nicholas Casey, the New York Times reporter who revealed, in May 2019, the new army leadership’s return to insisting on “body counts” as a measure of success. When that story was published, María Fernanda Cabal, a senator from Duque’s and Uribe’s political party, tweeted a photo of Casey, accusing him of taking payments for reporting against the army. Casey has since left Colombia.

“The order from the commanders of the Bacib, Caimi, and Cacim was that, on the instructions of the general [Martínez], we had to obtain everything we could about the gringo reporter, especially because they considered that, for what he had published, he was attacking the institution and Gen. Martínez in particular,” a military source told Semana. “We had to find out who he spoke with for that and, in addition, to obtain elements with which to try to discredit him and his newspaper.”

The data-gathering on Casey snowballed into data-gathering on other longtime foreign correspondents in Bogotá. The army built dossiers on Juan Forero of the Wall Street Journal, John Otis of NPR and the Committee to Protect Journalists (who appears in a March 2020 WOLA podcast), and photojournalists Lynsey Addario and Stephen Ferry, among others.

Files also exist on veteran Colombian journalists like María Alejandra Villamizar of Caracol Radio, Daniel Coronell of Univisión (until recently a Semana columnist), Ignacio Gómez of Noticias Uno, Gina Morelo of El Tiempo, and an unnamed reporter for Blu Radio who had helped to arrange interviews with ELN leaders in Chocó department. Rutas del Conflicto, a collective of young investigative journalists, came under surveillance after submitting an information request to the army about questionable contracts.

Non-governmental organizations known to be under surveillance include the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective, a decades-old group that frequently represents victims of military human rights violations; Humberto Correa, the human rights secretary of the General Confederation of Workers (CGT) labor union; and Human Rights Watch’s Americas director, José Miguel Vivanco.

The army’s files also included politicians, among them center-left senators Gustavo Bolivar, Angélica Lozano, and Antonio Sanguino.

They also included military figures: retired Captain César Castaño, who had assisted the government’s negotiating team during the FARC peace process; retired Gen. Jorge Maldonado, who headed the presidency’s military office during Juan Manuel Santos’s administration; retired Gen. Carlos Lemus, the number two official in the military justice system; retired Gen. Rodolfo Amaya Kerguelen; his brother, presidential intelligence chief Gen. Juan Pablo Amaya; retired Col. Enrique Villareal, a former chief of the military’s weapons maker Indumil; and retired Col. Vicente Sarmiento, an advisor to President Duque’s chief peace advisor Miguel Ceballos.

Significantly, there is also a file on Jorge Mario Eastman, a former vice-minister of defense who served as President Duque’s chief of staff until being named Colombia’s ambassador to the Vatican several months ago. Eastman, La Silla Vacía reports, “was profiled a week after he went to Semana to try to convince them not to publish their investigation about the directive” about body counts in May 2019, which the New York Times revealed instead. “Eastman,” this report goes on, “was viewed with suspicion by members of the Democratic Center,” President Duque’s political party. Speaking to Caracol from the Vatican, Eastman called the revelations “an attempt to obtain illegal information on the president himself.”

It’s far from clear whether Colombia will achieve true accountability for what appears to be a blatant violation of the country’s 2013 intelligence law and other statutes. For now, top officials are striking a tough tone, but the usual pattern is for such statements to stop within a week or two, when Colombia’s civic discussion moves on.

“The profilings of journalists and even public officials are inadmissible and the full weight of the law must fall on those responsible,” said President Duque. “No member of the security forces will be allowed to act against the law.” Defense Minister Carlos Holmes Trujillo said that the government’s policy is “zero tolerance” for lawbreaking, and that he will be firm in “making decisions,” Armed Forces Chief Gen. Luis Fernando Navarro told Reuters, in a paraphrased quote, that “illegal spying is not an institutional policy but reflects the individual actions of a few officials who have not just lost their jobs but could face jail time.” Gen. Zapateiro, the army chief, said that he is making significant changes to the leadership of intelligence and counterintelligence commands, without offering more specifics.

On May 1, minutes before Semana put its new findings online, Defense Minister Holmes Trujillo announced that 11 senior officers were being fired. The list includes five colonels, three majors, and a general, while a second general offered his resignation. Gen. Eduardo Quirós, former commander of the Cacim counterintelligence unit, was already known for his commanding role in the 2019 effort to root out military whistleblowers who had contacted the New York Times, Semana, and other outlets. Gen. Gonzalo Ernesto García Luna, who took over the military’s Joint Intelligence and Counterintelligence Department in December 2019, had a lower profile and wasn’t known to be facing accusations.

For his part, Gen. Martínez, the former army chief, was just informed that the Defense Ministry will not be naming him to lead the Defense Attaché’s Office at Colombia’s embassy in Brussels, where he would have been the military’s main interface with NATO. The Attorney-General’s office will be questioning him in its investigation of “the crimes of illicit violation of communications” and “illicit use of transmission and reception equipment.” This investigation began in January; it is not clear why investigators had not called on Gen. Martínez before.

For his part, the now-retired General continues to deny everything. He called the May Semana report “insults, slanders, and injustices against me. I feel like a victim.” He added, “I don’t have the slightest idea who could be behind all of this. It’s a disinformation war, and I’ve been made a scapegoat.… I fear for my life, for the security of my family.”

President Duque said that he had called on Defense Minister Holmes Trujillo, when he took over in November, to carry out a “rigorous investigation of intelligence work over the past 10 years.” Gen. Navarro, the maximum armed forces chief, said that this review has been ongoing since December and that there will be “disciplinary processes, criminal investigations, and measures to reorganize this organism within the army.”

Any effort to achieve accountability for the crimes of Colombian army intelligence will face an uphill struggle. The Truth Commission created by the 2016 peace accord, for instance, noted that “in December 2017 the National System for the Purging of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Archives was created, but no results have been noted.”

A military source told Semana that top commanders must have known what was going on.

Everything that was done, and that happened with these special tasks, was known by the commanders. But when this all ends, those who will pay will be the idiots [pendejos], as always. Civilians don’t understand something called “reverential fear,” in which a subordinate carries out orders under pressure, fear, or threats from his superiors, that’s why many of us carry out our instructions. But the intelligence and counterintelligence chiefs of that moment, Generals Quirós and García, knew about it. The army commander knew about it, and even the commander of the armed forces knew about it.”

Semana casts further doubt on theories that this was the work of rogue officers or “bad apples,” noting,

To spy on an agency charged with spying, such as the top men in the presidential palace, is clearly not something that occurs to subordinate or low-ranking officers. Nor is it a step that a general could easily take on his own initiative without the knowledge of his force’s commanders, since the risks, upon being discovered, are enormous.

A resounding editorial in El Espectador laid out what is at stake for Colombia.

We Colombians finance with our taxes, and vehemently support, the army on the understanding that it is an institution that protects us, that respects the Constitution, and is not an apparatus at the service of certain political ideologies. When it takes advantage of its capabilities to carry out surveillance, it ends up being terrorism with government funding and international aid. The appropriate word is treason: to the basic principles of democracy and to the agreement between our public forces and society.

That’s why it is so frustrating to see that the official response is the same as always. The Presidency rejects what happened, the Ministry of Defense announces investigations and withdrawals, but nothing more profound happens.

And that is the fear: that this scandal might blow over and nothing more will happen. Sen. Juan Manuel Galán, who sponsored the 2013 intelligence reform law, told El Colombiano that “the civilian criminal justice system must respond to this, not the military justice system, because the crimes committed by these officers within the army were not part of their functions as soldiers.”

Galán is right: the best way to guarantee that Colombia stops repeating this pattern of undemocratic abuse of intelligence capabilities is for those responsible, at the highest levels, to be convicted after a fair trial in the civilian justice system. This deterrent is indispensable.

In order to get there, international vigilance and pressure will be important. It is especially important because this is not an entirely domestic matter. Some of the equipment that was abused to surveil the army’s targets, including U.S. journalists, appears to have been provided by the United States and perhaps other foreign governments, which support these army intelligence units.

Semana reported this in January, when it revealed the first army hacking allegations.

The first indication that something was wrong reached the ears of U.S. intelligence agencies. These had donated a pair of sophisticated technical devices, but began receiving information that some military personnel were using them for illegal ends. And that some economic support to pay sources who could have provided valuable information was ending up in some officers’ pockets.

After its January report, Semana “confirmed with U.S. embassy sources that the Americans recovered from several military units the tactical monitoring and location equipment that it had lent them.” La Silla Vacía reported that the U.S. agency in question was the CIA.

Semana also notes that “a foreign intelligence agency” has given Colombia’s cyber-intelligence agencies approximately USD$400,000 per year for equipment and tools. A military source told the magazine, “The Americans aren’t going to be happy that part of their own money—from their taxpayers, as they say—has been diverted from the legitimate purposes for which they were given, the fight against terrorism and narcotrafficking, and ended up being used to dig up dirt on journalists from their own country’s important media outlets.”

The May Semana article has a quote from Sen. Patrick Leahy who, as the senior Democrat on the Senate Appropriations Committee, has a strong role in determining what kind of assistance Colombia receives.

The allegations of illegal intercepts and secret monitoring of journalists and human rights defenders will be seriously examined when determining U.S. military assistance to Colombia. U.S. taxpayers’ money should never be used for illegal activities, much less to violate the rights of American citizens. If these allegations are correct, it would be a serious breach of (America’s) trust, and those involved must be punished.

If Sen. Leahy’s words go ignored—if those involved are not punished—then Colombia’s free press, human rights defenders, independent political leaders, and would-be whistleblowers will continue to have much to fear from their country’s army. And U.S. military assistance will have to be deeply cut and thoroughly reappraised.

For now, there is much more that we need to know. Who were the rest of the 130 victims of the army’s spying? How many are threatened human rights defenders? Are more of them U.S. citizens? Do they need additional protection now, and if so, what is the Colombian government’s National Protection Unit doing to provide it?

Who gave the order? What was Gen. Nicacio Martínez’s true role? Who outside the military benefited from these wiretaps? Much unproven speculation surrounds former president Álvaro Uribe, who has been one degree of separation from past wiretapping scandals. Did he or his circle receive information?

With so many repeated scandals, are the culprits really an entirely different crop of “bad apples” each time? That strains credulity. Is it not more likely that we are dealing with the same faction or political group? And if so, what will it take to break the grip that they apparently have over the rest of the institution and over government investigators and prosecutors?

Which army intelligence units have been recipients of U.S. assistance? What equipment did the U.S. government provide, from which agencies, and through which funding sources?

According to the Leahy Law, which conditions U.S. foreign assistance, foreign security force units that commit gross human rights violations with impunity cannot receive aid. The future of U.S. aid to Colombian military intelligence, then, hinges on impunity. Is the civilian justice system finding itself able to investigate the crimes revealed by Semana, or are its members being stonewalled or even threatened? If there is any indication that these crimes are in danger of going unpunished yet again, this time it must trigger a Leahy Law suspension of all assistance to the Colombian army’s intelligence units.