(AP Image/Cubillos)

(AP Image/Cubillos)

As the crisis in Venezuela drags on and Nicolás Maduro continues to cling to power, many in Washington are evaluating ways to put additional pressure on actors in the government. While some have suggested that it is time to begin pursuing indictments against figures in Maduro’s inner circle, so far the U.S. government has relied on offers of relief to key sanctioned figures to get them to flip. A look at events in recent weeks suggests there is increasing evidence that these offers of sanctions relief—a much more flexible tool than indictments—have advanced the dominant U.S. strategy of sowing divisions around Maduro.

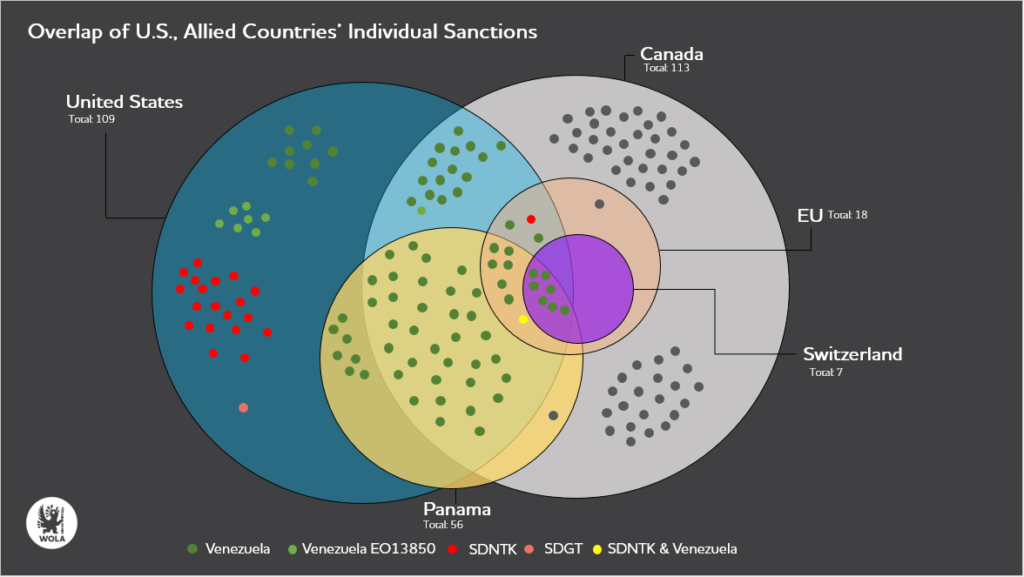

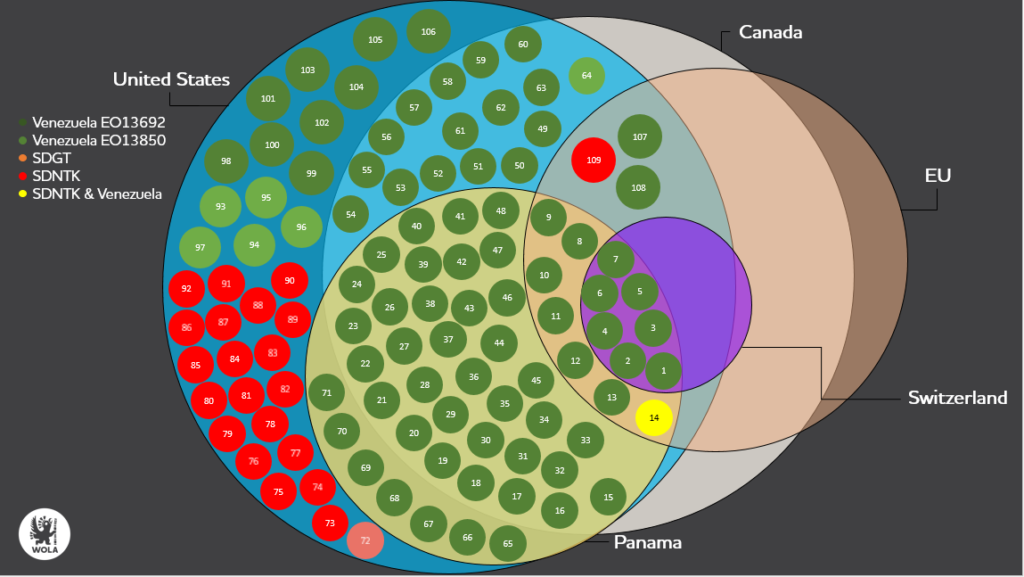

Since 2018, WOLA has been tracking targeted sanctions against individuals in the Maduro government in our Venezuela Targeted Sanctions Database (see updates from March, April, and September 2018). The database maps out all of the individuals in Venezuela currently sanctioned by the U.S. government, as well as the specific policy instrument used to implement the sanction. These are: Executive Orders 13692 or 13850 (marked in dark and light green in Diagram A below), the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions Regulations (marked SDNTK in red), or the Global Terrorism Sanctions Regulations (SDGT in light red).

We also track overlap between the U.S. and allied countries, monitoring which specific individuals (see Diagram B further down) have been sanctioned by the other governments and groupings that have issued individual sanctions: Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, and Panama.

Diagram A (see larger version here)

Below are five clear takeaways from our latest update to our database, as well as some of the important movement seen in the last few weeks regarding individual sanctions.

At WOLA we have been consistently concerned about the potential for targeted sanctions to raise the “exit costs” of Venezuelan political elites. As David Smilde put it in his 2017 testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, we’ve argued that there is a risk that once an individual is sanctioned their incentives to support a transition could be reduced—instead giving them incentives to go down with the ship.

However, we’ve also noted that this effect can be curtailed if the implementation of sanctions is accompanied by a communications strategy that lays out what steps targeted officials can take to get themselves from the list of “Specially Designated Nationals,” or SDNs. In September, we saw the U.S. government start to recognize this dynamic. Beginning in September 2018, both the State Department and Treasury began including the following language in their announcements of new individuals added to the sanctions list (emphasis added):

“U.S. sanctions need not be permanent; they are intended to change behavior. The United States would consider lifting sanctions for persons sanctioned under E.O. 13692 that take concrete and meaningful actions to restore democratic order, refuse to take part in human rights abuses and speak out against abuses committed by the government, and combat corruption in Venezuela.”

Beginning in February 29, this language shifted. It was changed to:

“U.S. sanctions need not be permanent; sanctions are intended to bring about a positive change of behavior. The United States has made clear that the removal of sanctions is available for persons designated under E.O. 13692 or E.O. 13850 who…”

This is an important shift, as “the removal of sanctions is available” is a far stronger guarantee than suggesting the U.S. government “will consider” lifting them. Note that this language applies not only to those sanctioned under Executive Order 13692 (which was issued under the Obama administration and laid the groundwork for individual sanctions) but also to Executive Order 13850, which was signed by President Trump in November 2018 and set the groundwork for the current gold and oil sanctions.

However, this offer does not include those publicly linked to drug trafficking or terrorism. Thus sanctions relief is not—at least publicly—on the table for all those sanctioned under Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions Regulations (marked SDNTK in red in Diagram A), or Global Terrorism Sanctions Regulations (SDGT in light red).

Even still, the offer of sanctions relief is a pretty broad one taken at face value. Because they have all have been sanctioned by E.O. 13692 or E.O. 13850, in theory this offer extends to Nicolás Maduro, his Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, Communications Minister Jorge Rodríguez, Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López, Prisons Minister Iris Varela, and Prosecutor General Tarek William Saab—provided the U.S. deemed they take “concrete and meaningful actions to restore democratic order.”

There is one case in which it is unclear if sanctions relief is available or not: Freddy Bernal, marked in yellow in both diagrams. The Chavista former lawmaker and current head of the CLAP program was first sanctioned under the Kingpin Act in 2011 (sanctions which are not subject to relief), then sanctioned again under E.O. 13692 in 2017 (which are).

Diagram B (See full version here, with the corresponding key of names)

It has become clear that the United States relied on communication with sanctioned individuals as part of the plans around Juan Guaidó’s failed April 30 uprising. The clearest sign of this was the U.S. decision on May 7 to lift sanctions against the former SEBIN intelligence director who is alleged to have helped Leopoldo López escape house arrest, General Manuel Cristopher Figuera. Interestingly, Figuera was sanctioned by the Canadians on April 15 and there has been no similar announcement from Ottawa that he has been taken off of their list.

In recent days it has also been made public that media mogul Raul Gorrín, who was sanctioned in January, played a key role in promoting the April 30 plot to other key targets in Maduro’s inner circle: Supreme Court Chief Justice Maikel Moreno, Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López, and military counterintelligence chief Ivan Hernández. As the Wall Street Journal has reported, Gorrín attempted to sway these three individuals by promising them that the U.S. government would lift sanctions against them. As evidence of this, Gorrín was able to point to the fact that his wife and the wife of his business partner were quietly removed from the SDN list in March. While Gorrín himself could in theory be eligible for sanctions relief himself, his indictment in November creates an added obstacle.

Judging from the fact that John Bolton was appealing to Padrino López to flip against Maduro over Twitter as recently as June 2, the White House seems to believe these individuals can still play an essential role in a transition. If this strategy continues, we can likely expect to see more individuals receive sanctions relief in the coming weeks and months—provided they flip.

Just as interesting as those who have been taken off the list are those who have defected, but still remain on it. On May 20, for instance, Maduro’s ambassador to Italy Isaías Rodríguez published a public letter of resignation to Maduro on May 20. In his letter he expressed his continued loyalty to Chavismo even as he offered florid but vague criticisms of Maduro. Most relevant, he complained that “I do not have a bank account, because the gringos sanctioned me and the Italian bank threw me out of their market.” So even as he bemoaned the impact of sanctions, Rodríguez publicly appeared to take no “concrete or meaningful actions” that would grant sanctions relief, beyond publishing a letter.

Another such case is General Carlos Rotondaro, former head of Venezuela’s state social security institute. Rotondaro fled to Colombia in March 2019, and has made statements to the press in which he not only criticized Maduro but also recognized Juan Guaidó as president. Nevertheless his name is still on the OFAC list, an indication that the U.S. government is looking for more from him before taking him off the list.

Individuals sanctioned under the Kingpin Act provide an interesting contrast to individuals who have been sanctioned and are eligible for sanctions relief. Some of those sanctioned under Kingpin, like former Vice President Tareck El Aissami (who is also under indictment), have shown no signs of turning against the Maduro government. But there have been two who have.

The most high-profile case is that of Hugo “El Pollo” Carvajal, Chávez’s former spy chief who has sanctioned since 2008 and under indictment since 2014 for drug trafficking and for ties with the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Carvajal was detained in Spain in April, and is currently battling an extradition request from the United States. In the months leading up to his arrest—and since—has made numerous public statements accusing Maduro and his confidantes of corruption and calling on the military to depose him.

Less well-known is retired Major General Cliver Antonio Alcalá Cordones, who was sanctioned in 2011 for allegedly establishing an “an arms-for-drugs route” for the FARC. Cliver Alcalá—who lives in Colombia—has publicly criticized Maduro since at least as far back as early 2018, and in early 2019 began organizing military defectors to provide armed support to the failed February 23 humanitarian aid delivery in Cúcuta. The Colombian government reportedly put a stop to his initiative out of a concern for violence.

Both of these individuals, despite making plenty of noise, have not been removed from the U.S. sanctions list. In Carvajal’s case, it is unclear how useful he could really be to the U.S. government given the fact that he was effectively sidelined when Maduro came to power. Cliver Alcalá may be of similarly limited usefulness to the U.S. government, as despite its bluster so far the United States does not appear to be interested in pursuing what could easily turn into a Contra War in Venezuela.

Though offering sanctions relief to individuals emerges as a dominant tool of the U.S. government strategy in Venezuela, it remains to be seen how effective such offers can be at lowering exit costs for individuals. As Venezuela’s crisis has dragged on and repression has worsened, rhetoric from U.S. officials and the opposition has grown sharper. Today there are reasons for figures in Chavismo to be skeptical of off ramps. The National Assembly’s much-publicized amnesty proposal, for instance, has not actually been voted on and appears to have stalled. There is increasing documentation of torture and killings as evidence of crimes against humanity (see Amnesty International’s recent report), which some have used to argue against a pacted transition. The preliminary examination of the International Criminal Court may be weighing on the minds of those around Maduro as well. A transition of any sort will have to rely on strategies of reducing exit costs for Venezuelan elites. But doing so will require credible offers in an environment in which a transition is increasingly being framed as a zero-sum game for these figures.

(Graphics by Kristen Martinez-Gugerli)