With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since what’s happening at the border is one of the principal events in this week’s U.S. news, this update is a “double issue,” longer than normal. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Tucson Police Chief is CBP commissioner nominee

On April 12 the Biden White House revealed its nominee to head U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the agency that includes Border Patrol and all land, sea, and air ports of entry. Chris Magnus, the current chief of police of Tucson, Arizona, would be only the second Senate-confirmed CBP commissioner since January 2017: except for Kevin McAleenan’s 13-month tenure in 2018 and 2019, all commissioners since then have been in an “acting” role.

A native of Michigan, Magnus has served as police chief in Fargo, North Dakota; Richmond, California; and, since 2016, Tucson, a city about an hour’s drive from the U.S.-Mexico border. While heading this 1,000-person department, he has favored community policing, de-escalation, and other law enforcement strategies often labeled as “progressive.” Magnus was the 2020 recipient of the Police Executive Research Forum’s (PERF’s) Leadership Award. (The Obama administration, under then-CBP commissioner Gil Kerlikowske, had hired PERF to perform a 2014 review of the agency’s use-of-force policies.)

Though he opposed a 2019 ballot initiative to declare Tucson a “sanctuary city” refusing to share information with ICE about detained individuals, Magnus has a broadly liberal record, which at times has earned him “frosty” relations with Border Patrol, as the Washington Post put it.

- In 2014, as chief of the Bay Area city of Richmond, California, Magnus was photographed holding a “Black Lives Matter” sign.

- In March 2017, he cut short his department’s cooperation with a Border Patrol manhunt for an apprehended migrant who had escaped a hospital, angering the agency. The following year, Border Patrol’s hardline union, which endorsed Donald Trump in the 2016 primaries, called Magnus “an ultraliberal social engineer who was given a badge and a gun by the City of Tucson” in a Facebook post.

- In a 2017 New York Times op-ed, Magnus argued that the Trump administration’s rhetoric and policies were complicating law enforcement because undocumented communities were less willing to come forward with information.

- In June 2018 he tweeted strong opposition to the Trump administration’s child separations policy, asking, “Is this consistent with the oath you took to serve & protect? Is this humane or moral? Does this make your community safer?”

- He opposed the Trump administration’s border wall in December 2018 congressional testimony and a February 2019 NPR interview.

- In 2019, amid an increase in asylum-seeking migration, Magnus tweeted, “it’s worth being reminded why human beings flee from their homelands in the first place (not unlike a lot of our ancestors).”

- In 2020, Magnus refused to accept so-called “Stonegarden” grants to local law enforcement from Trump’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS), because the administration was prohibiting expenditures for humanitarian aid to asylum seekers.

Magnus’s nomination received statements of support from both of Arizona’s Democratic senators. If confirmed, he would be the first openly gay CBP commissioner.

The White House also revealed its nominee to head U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS, the DHS component that runs legal immigration, including refugee and asylum processing). As expected, it is Ur Jaddou, who was a senior USCIS official during the Obama administration. During the Trump years, Jaddou worked at the progressive immigration reform group America’s Voice, where she ran an oversight campaign called DHS Watch.

The Biden administration has yet to name a director to lead Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Unaccompanied children situation may be easing; family expulsions continue

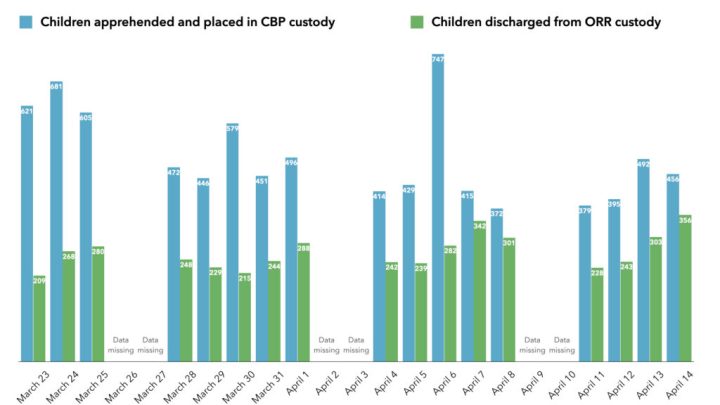

Data about unaccompanied migrant children in U.S. custody point to a modest easing of the situation, after weeks of concern about children packed into inadequate CBP and Border Patrol facilities. As of April 14:

- Border Patrol had apprehended a daily average of 431 unaccompanied non-Mexican children so far this week, down from an average of 475 per day the previous week and 489 the week before that.

- The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) has been taking over 700 children per day out of CBP custody during the past two weeks, placing them in its network of shelters and emergency facilities.

- With more kids leaving CBP custody than entering it, the number stuck in CBP’s holding facilities has dropped sharply, from 5,767 on March 28 to 2,581 on April 14. CNN reported on April 12, however, that the average child still spends about 122 hours in CBP custody, far exceeding the 72 hours required by law.

- The number in ORR’s shelter network has marched steadily upward, from 11,551 on March 23 to 19,537 on April 14. It should top 20,000 any day now.

- ORR still faces challenges in getting kids out of its shelters, placing them with relatives or sponsors in the United States. ORR discharged a daily average of 281 children per day last week, which increased only to 283 per day so far this week.

- Subtracting the number leaving ORR custody from the number newly entering CBP custody reveals the net daily overall increase of children in the U.S. government’s care. That daily increase averaged 194 children per day last week, and 148 per day so far this week. For the population of unaccompanied kids in U.S. custody to fall, this daily number needs to fall into negative territory. On this chart, the green needs to start exceeding the blue:

Getting children out of ORR custody is the most urgent bottleneck right now. While more than 80 percent of children have relatives in the United States, shelters still must perform some vetting to ensure that they are not inadvertently handing children off to traffickers. The agency has also been occupied trying to stand up large temporary facilities around the country to create space to get kids out of CBP’s austere holding spaces.

Reuters reports that White House officials—especially domestic policy adviser and Obama-era national security advisor Susan Rice—are exerting pressure on ORR and its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to move faster. A source tells the wire service that “getting yelled at” in interagency meetings is taking a toll on ORR and HHS staff. “Everyone’s working around the clock, and there’s a big morale issue,” an official said. “These are people who signed up to help kids.”

ORR “has temporarily waived some vetting requirements, including most background checks on adults who live in the same household as sponsors who are close relatives,” according to Reuters, and has reduced the amount of time children spend in its shelters from 42 to 31 days. Still, Neha Desai, an attorney with the National Center for Youth Law, told Reuters that the majority of kids in the emergency shelters still don’t have case managers assigned to them to begin vetting their relatives.

As the number of unaccompanied children newly arriving declines, it’s likely that the number of migrants arriving as intact family units continues to increase. While we haven’t seen numbers from April, this was the fastest-growing category of apprehended migrant at the border in March, growing 174 percent over February.

Unlike unaccompanied children, the Biden administration is endeavoring to use a Trump-era pandemic order to expel back into Mexico, in a matter of hours, as many families from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (the “Northern Triangle” countries) as it can. In nearly all cases, these so-called “Title 42” expulsions happen without regard to families’ fear of returning to their countries.

As the number of family members from the Northern Triangle increases (40,582 in March), Mexico has hit limits. It is accepting expulsions of a larger number, but a smaller percentage, of families: about 31 percent of the total in March. Mexico cites a late 2020 law that prohibits detention of children in adult facilities. Mexico’s law “certainly snuck up on us,” a senior Biden administration official told the Washington Post.

Of the nine sectors into which CBP divides the border, by far the most arrive in south Texas’s Rio Grande Valley region. There, Border Patrol is processing families outdoors under the Anzalduas International Bridge near McAllen and at a nearly adjacent temporary site known as TOPS. Indoor processing happens at a large tent facility in nearby Donna. These sites are mostly off-limits to reporters, but the Rio Grande Valley Monitor shared some drone footage this week showing Border Patrol agents with bullhorns lining families up on benches.

CBP continues to expel large numbers of Central American families, particularly those with older children, each day from the Rio Grande Valley into dangerous Mexican border towns like Reynosa and Matamoros. When Mexico refuses expulsions in this region, DHS puts about 200 family members per day on planes to El Paso and San Diego, from where they expel them into Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana. (100 per day per city appears to be a limit that Mexico has set.)

Expelled migrants interviewed by the New Humanitarian in Juárez and by the San Diego Union Tribune in Tijuana coincide in saying that U.S. agents “tricked” them, lying that they were being admitted into the United States while boarding them on aircraft out of Texas. They only discovered they were returned to Mexico after their U.S. escorts left them there. Both border cities have seen distraught Central American parents forced to ask strangers what city they were in.

In Tijuana, Mexican authorities give the families a 30-day permit to remain in the country with instructions to return to their home countries. They are then taken to one of the city’s very full, mostly charity-run, migrant shelters.

Meanwhile, as last week’s update noted, more than 11 expelled families per day appear to be making the terrible decision to separate while in Mexican territory. Knowing that unaccompanied children aren’t being expelled, parents who find themselves returned to Mexico are sending their children to walk north, across the border, alone. CNN—which reported that Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol had apprehended, in a 28-day period, 435 unaccompanied children who had already been expelled with their parents—spoke to tearful expelled parents who had said goodbye to their children at the borderline.

Mexico’s deployment of forces gets scrutiny

Senior officials revealed this week that the Biden administration recently reached agreements with Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala to deploy more security forces to deter migration, without mention of migrants’ protection or asylum needs. These agreements appear to be informal rather than written.

Tyler Moran, the White House Domestic Policy Council’s special assistant to the President for immigration, told MSNBC on April 12, “We’ve secured agreements for them to put more troops on their own border. Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala have all agreed to do this.” Moran insisted that such action “not only is going to prevent the traffickers, and the smugglers, and cartels that take advantage of the kids on their way here, but also to protect those children.”

Later that day, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki gave reporters a bit more detail.

[T]here have been a series of bilateral discussions between our leadership and the regional governments of Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala. Through those discussions, there was a commitment, as you mentioned, to increase border security.

So, Mexico made the decision to maintain 10,000 troops at its southern border, resulting in twice as many daily migrant interdictions. Guatemala surged 1,500 police and military personnel to its southern border with Honduras and agreed to set up 12 checkpoints along the migratory route. Honduras surged 7,000 police and military to disperse a large contingent of migrants.

Psaki attributed these moves to “discussions with the region about what steps can be taken to help reduce the number of migrants who are coming to the U.S.-Mexico border,” adding, “I think the objective is to make it more difficult to make the journey and make crossing the borders more—more difficult.”

This was news in Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, where leaders had made no prior reference to agreements with the United States. Honduras’s defense minister, Fredy Díaz, confirmed that an agreement existed. He added that at the moment, his country is not moving new security forces to its border with Guatemala to interdict migrants. Instead, he told the Honduran network HRN, his ministry is working on a plan for military support to police to slow migration, insisting that “the armed forces have stood out for their respect for the law and human rights.”

On April 13 Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, confirmed to reporters that his government had deployed at least 12,000 officials to the country’s southern region, including immigration agents, soldiers and national guardsmen, and health and child welfare officials. Mexico had said on March 22 that nearly 9,000 troops and guardsmen were stationed near its northern and southern borders.

López Obrador portrayed the deployment as an effort to protect migrant children. “We’ve never seen trafficking of minors on this scale,” he said, adding, “To protect children we are going to reinforce the surveillance, the protection, the care on our southern border because it’s to defend human rights.” The president appeared to allege that smugglers are using children to help migrants pass as family units, a practice that occurs, but not frequently.

López Obrador said he will meet next week with the governors of Mexico’s southern states that border Guatemala and Belize, and that the director of the country’s child and family welfare agency (DIF) would relocate for some time to the southern border-zone city of Tapachula. He promised that Mexico would accompany the United States in increasing investments to create economic opportunity and alleviate migration’s “push factors” in Central America, including through aid programs like “Sembrando Vida” and “Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro,” which to date have devoted very few resources.

Tonatiuh Guillén, a leading Mexican migration expert who briefly headed Mexico’s migration authority (INM) at the beginning of the López Obrador government, lamented to the Guardian that his country’s migration system has “turned into a very strong and very heavy control apparatus, largely due to pressure from the U.S. government.” Reporting from the remote Mexico-Guatemala border crossing of Frontera Corozal, however, Guardian reporter David Agren saw no evidence of a crackdown: “it looked like business as usual” as Central American families crossed the Usumacinta River and began a long walk through the edges of the Lacandón jungle en route to Palenque, Chiapas.

Some Mexican security forces are arrayed along this jungle route, Agren reported, manning checkpoints. “But migrants said they simply paid to pass through – or were robbed by the officers they met.” The prevalence of corruption among the Mexican forces deployed to control movement in the southern border zone is a large unaddressed factor as the López Obrador government sends more personnel. “It’s a cartel. They’re acting in cahoots with smugglers…with taxi and bus drivers. It’s a network taking advantage of migrants,” Father Gabriel Romero of the “La 72” migrant shelter in Tenosique told Agren. Added Guillén, the former INM director: “Governments in Mexico, the United States and Central America have never really put much of an effort into controlling these trafficking organizations.”

No pause to border wall property seizures in Texas

The White House’s 2022 discretionary funding request to Congress, a summary document known as the “skinny budget,” would end border wall construction. It requests $1.2 billion for CBP’s border security infrastructure needs, but specifies that none will go toward border barriers. It also “proposes the cancellation of prior-year balances that are unobligated at the end of 2021,” shutting down any previously funded construction.

That doesn’t necessarily stop border wall construction, however, during fiscal 2021, which ends on September 30. For now, wall-building has been “paused” since Inauguration Day, but contracts have not been canceled. As noted in last week’s update, CBP may have communicated to DHS a preference to continue building in areas where the pause in construction has left “gaps.”

In south Texas, where most land bordering the Rio Grande is privately held, the Justice Department has not stopped eminent domain proceedings to seize more than 215 property owners’ land for wall construction. On April 13 the Cavazos family, which has held riverfront property since Texas was under Spanish rule, saw a court order the condemnation of 6 1/2 acres of its farmland. “We are utterly devastated,” Baudilla Cavazos said in a statement. “We thought President Joe Biden would protect us. Now we’ve lost our land. We don’t even know what comes next.”

In February, the Justice Department had postponed the Cavazos family’s land seizure case, which has been before a U.S. district court. When it came up again in April, Justice did not seek to postpone again, for unclear reasons.

Throughout the border zone, environmental activists and tribal leaders “are urging the government to begin habitat restoration efforts and take down sections of wall that are blocking wildlife migration pathways so that animals can once again move freely,” the Arizona Republic reported in a very detailed piece documenting damage to desert ecosystems. In Arizona, “We watched in horror as construction crews dynamited our ancestors’ gravesites, chopped ceremonial plants to bits and cleaved our sacred lands in two with a deadly mass of metal,” wrote Tohono O’odham Nation community organizer Hon’mana Seukteoma in a Medium column. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, meanwhile, called for a return to the formula of immigration reform with a large increase in border security, which he called “high wall, big gate.”

Links

- In a new edition of WOLA’s Podcast, four staff experts look at Mexico’s response to the increase in migration, including Mexico’s U.S.-encouraged deployment of security forces and acceptance of more expelled Central American families.

- Vice President Kamala Harris has been learning about “root causes” of migration from Central America, including a virtual meeting on April 13 with directors of several organizations (including WOLA). She may visit the region “soon.” As the Biden administration’s point person for working with the region, the vice president faces the dilemma of working with Central American leaders who “are considered complicit” in creating some of the conditions causing people to migrate, the Los Angeles Times observes.

- Local activists ridiculed Republican members of Congress who, on a visit to the Rio Grande Valley, boarded a Texas Department of Public Security gunboat. Wearing tactical vests and with a Fox News crew in tow, the delegation motored past a playground, waterslide, and picnic areas on the Mexican side of the river.

- Asked repeatedly about the border and migration situation at an April 13 House Armed Services Committee hearing, the general and admiral who command U.S. Northern Command and U.S. Southern Command sought to emphasize the multiple, complex causes of the current large-scale migration and the need for a “whole of government” response.

- A report and series of working papers from the Migration Policy Institute surveys how “to lay the foundation for a regional migration system that privileges safe, orderly, and legal movement,” evaluating current legal frameworks and asylum capacity in Mexico, the Northern Triangle, Costa Rica, and Panama.

- At the Intercept, Ryan Deveraux talked to beleaguered humanitarian volunteers helping asylum-seeking families whom Border Patrol, upon releasing them from custody, is leaving in Arizona desert towns with few services.

- In a key family separation lawsuit, the Biden administration’s Justice Department has decided not to share internal documents revealing the Trump administration’s decisionmaking leading up to the 2018 “zero tolerance” policy that caused DHS to take thousands of migrant children away from their parents. Among the documents that will remain classified, NBC News reports, is “the agenda from a May 3, 2018 meeting, which… included a show of hands vote to move forward with separating families.”

- Reuters points out that the White House’s 2022 “skinny budget” includes a 22 percent increase in funding for internal affairs offices at CBP and ICE, partially to “ensure that workforce complaints—‘including those related to white supremacy or ideological and non-ideological beliefs’—are investigated quickly.”

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson