With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Unaccompanied child population declines, temporary shelters pose challenges

Daily reports from the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Health and Human Services (HHS) point to a slow month-long decline in arrivals of unaccompanied migrant children at the U.S.-Mexico border, after a record-breaking, headline-grabbing increase in March.

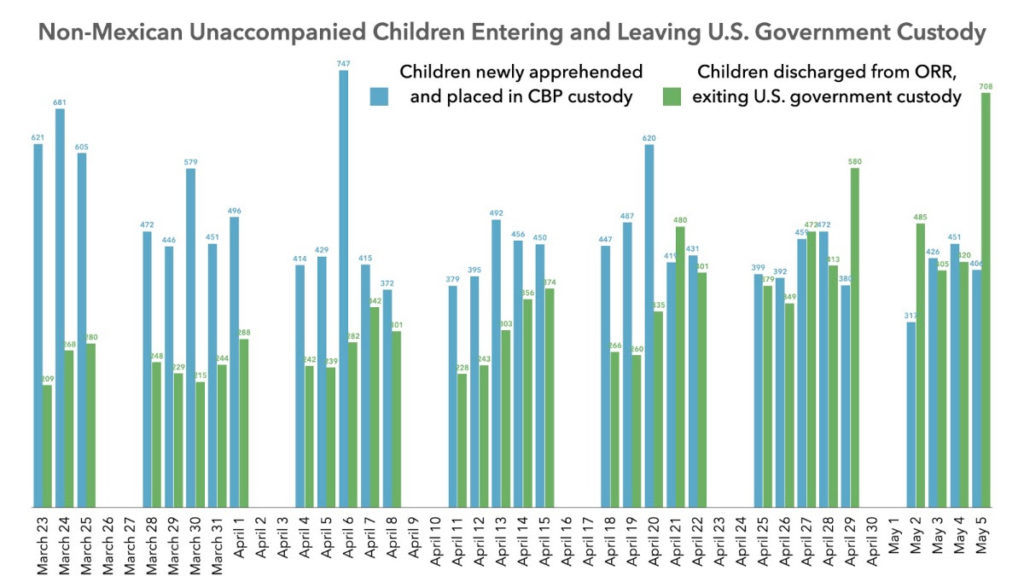

Border Patrol encountered an average of 400 unaccompanied non-Mexican children per day over the four days between May 2 and May 5. That is down from 489 per day during the last week of March.

(These numbers don’t include unaccompanied Mexican children, who were 12 percent of all unaccompanied kids encountered at the border in March. A 2008 law mandating that unaccompanied migrant kids be turned over to the HHS refugee agency only applies to those from “non-contiguous” countries. Nearly all children from contiguous Mexico are swiftly returned, as Border Report noted this week.)

The reason for a decline during spring months, when numbers usually increase, is not clear. Aaron Reichlin-Melnick of the American Immigration Council posits that pent-up demand to migrate may explain the earlier February-March burst of arrivals. It was very hard to migrate from Central America during the COVID-19 pandemic’s initial months, and the Trump administration was implementing its “Title 42” quarantine policy so severely that it was rapidly expelling even unaccompanied children—until a judge stopped that practice last November. It’s possible that some of that pent-up migratory demand is now exhausted, so numbers are dropping a bit. But nobody really knows: it’s entirely possible that arrivals could start climbing again in May.

For now, though, the population of children in U.S. government (DHS plus HHS) custody is starting to edge downward. Over the past 10 days for which DHS and HHS have reported data, 479 more unaccompanied children departed U.S. government custody than entered it. HHS, through its Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), handed over 4,612 children to relatives or sponsors in the United States, with whom they will stay while their protection needs are adjudicated. Border Patrol took a smaller number newly into custody: 4,133.

As of May 5, 749 children were in Border Patrol’s austere holding facilities, awaiting transfer to ORR’s network of shelters. That is down from more than 5,700 at the end of March. Children are now transferred from Border Patrol to ORR in an average of about 24 hours, far less than the alarming 5 1/2 days or more that were the norm a month ago.

DHS posted a series of photos of CBP’s processing facility in Donna, Texas, where children had been occupying virtually every square foot of floor space in mid-March. Now, the holding spaces are nearly empty (though children are still lying on mats on the floor under mylar blankets). “The progress we have made is dramatic,” DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas told reporters on May 2.

The number of children in HHS/ORR’s network of about 200 shelters has also begun, very gradually, to decline, from a high of 22,557 on April 29 to 21,848 on May 5—3 percent over 6 days. ORR is endeavoring to minimize the length of children’s stay in these shelters, speeding up their placement with relatives or sponsors. The Wall Street Journal reports that the agency has cut the length of stay in its custody “from an average of 42 days at the start of the Biden administration to 29 days last month [April].” This owes in large part to “aggressive actions” to speed placements, the Associated Press reports, “such as by putting them on flights to be with their families.”

Normally, ORR’s shelters have capacity to hold about 13,500 children. With an assist from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), ORR set up emergency facilities in at least a dozen convention centers, camps, army bases, and similar large sites. Three administration officials told the Journal that these sites are “a short-term solution while they work to open more licensed shelters.”

While the temporary emergency shelters remain open, though, child welfare advocates worry about conditions. Mark Greenberg of the Migration Policy Institute compared them to “hurricane shelters” in the Journal’s reporting. While FEMA logistical support has been important, the same story reported, its rapid pace left some ORR staff “feeling that it had lost control over the quality of the locations being opened.” Two facilities, in Houston, Texas and Erie, Pennsylvania, were shuttered shortly after being opened in April. ORR places strict limits on access to its shelters, citing both public health and child privacy reasons. While understandable, this makes conditions in the unlicensed temporary facilities impossible to verify.

AP and the Daily Beast reported about some of the corporations and nonprofits that received over $2 billion in quick no-bid contracts to run these shelters and related logistics.

- Deployed Resources LLC, based in Rome, New York, could receive up to $719 million for a 1,500-bed tent shelter in Donna, Texas. This company assembled the notorious “tent courts” where asylum seekers in the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” program were subjected to immigration court proceedings via video conference in 2019 and 2020.

- Family Endeavors, based in San Antonio, Texas, could get up to $580 million for a facility in Pecos, Texas. Endeavors, whose CEO told AP, “Many nonprofits were asked but declined,” is also executing an $87 million contract from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to hold asylum seeking families in hotel rooms while their cases are being processed.

- Rapid Deployment Inc., based in Mobile, Alabama, has received two contracts totaling $614 million to manage the facility at Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, Texas.

- MVM Inc., based in Ashburn, Virginia, is getting a contract, and expansion of another, totaling $136 million for the transportation of migrant children to, and between, ORR facilities. The company gained notoriety during the 2018 family separation tragedy, when Reveal News reported that it was keeping migrant children, including some separated from their parents, in an empty office building in Phoenix. In July 2020, when the Trump administration was holding children in Texas hotels before expelling them under Title 42, the Texas Civil Rights Project posted a viral video of one of its lawyers being shoved into a hotel elevator by MVM guards yelling profanities at him.

Title 42 remains controversial

The Biden administration’s maintenance of the Title 42 public health policy continued to generate controversy even as DHS began to ease it slightly. The policy, which the Trump administration launched in March 2020, seeks to expel most undocumented migrant adults and families without regard to asylum needs, in an accelerated process. Mexico has agreed to take citizens of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. An April 20 report by Human Rights First, Al Otro Lado, and the Haitian Bridge Alliance documented at least 492 attacks on and kidnappings of expelled migrants since Joe Biden took office in January.

Authorities in Mexico’s state of Tamaulipas, citing a child welfare law that prohibits holding children in immigration detention centers, are not receiving most Central American families with children under seven years of age. Tamaulipas is across from south Texas; DHS has responded by flying daily planeloads of Central American asylum-seeking families to El Paso and San Diego, then expelling them into Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana. “At least a hundred people are returned to Juarez daily” from flights, in addition to those turned back at the border, Juarez’s municipal human rights director, Rogelio Pinal, told Texas Standard.

In March, Mexico appeared to be accepting expulsions of about 32 percent of the Central American families whom Border Patrol was encountering. Those who don’t get expelled are allowed to begin asylum petitions and released into the United States with notices to appear in hearings.

There is still no real rhyme or reason as to which families get to stay, and which are expelled, whether by land or air. “Some families are swiftly expelled without due process while others are allowed to stay in the U.S. because of where they entered, the age of their children, or sheer luck,” reported Camilo Montoya-Galvez of CBS News. “If a person wants to come to the United States right now, the only chance they have is to maybe go through Reynosa [across from McAllen] and be one of the lucky ones that doesn’t get expelled,” Linda Rivas of El Paso’s Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center told the Texas Standard, in an article highlighting the resulting overcrowding in Ciudad Juarez shelters. “That’s not an asylum system.”

While we haven’t seen April data yet, there is some likelihood that Mexico is accepting more Central American families border-wide. Sister Norma Pimentel, who runs the Catholic Charities Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, told Montoya-Galvez that “she has been receiving fewer families from U.S. border officials in recent weeks, compared to earlier in the spring. She said that is likely due to U.S. authorities expelling more families to Mexico,” including through the lateral flights.

Even while seeking to maximize family and single adult expulsions, the Biden administration has been moving to make exceptions for those whom advocacy groups identify as most vulnerable. Lee Gelernt of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) told CBS that his organization has been sending a daily list of people stranded in Mexico who are most endangered, so that they might be brought across and allowed to continue their cases in the United States. The definition of “vulnerable” isn’t clear, but El Paso Matters reported that a number of trans women have recently been able to cross to El Paso.

In Reynosa, a city of 700,000 that is probably the most dangerous of all Mexican border towns due to frequent disputes between organized crime factions, a park near the main port of entry continues to fill up with expelled non-Mexican families. Border Report estimates that over 700 asylum-seeking migrants are now in Reynosa’s Plaza de la República. Tents are going up, reviving miserable images of the tent city in nearby Matamoros that had filled up with “Remain in Mexico” subjects in 2019 and 2020. Doctors Without Borders told AP that the improvised site lacks water supplies or health services.

Reynosa’s security situation is a major concern. The Doctors Without Borders coordinator in Reynosa, José Antonio Silva, told AP, “We have reports of people disappearing day and night at the square, which is very worrisome.” A Texas-based charity, the Sidewalk School for Children Asylum Seekers—which first began working in the Matamoros camp—is now taking one or two of the most vulnerable families each day and paying to check them in to Reynosa hotels or apartments, says Border Report.

Mexico’s migration enforcement solidifies “buffer” role

On April 12, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki had told reporters:

Mexico made the decision to maintain 10,000 troops at its southern border, resulting in twice as many daily migrant interdictions. Guatemala surged 1,500 police and military personnel to its southern border with Honduras and agreed to set up 12 checkpoints along the migratory route. Honduras surged 7,000 police and military to disperse a large contingent of migrants.

As the Intercept notes, Guatemala and Honduras soon backpedaled from that, insisting that there had been no agreement to deploy personnel to block migrants. Mexico, however, did the opposite: “The Mexican government clarified that its efforts involved 12,000 people, though not just troops and not just to the southern border.” Mexico also closed its southern border with Guatemala to all non-essential travel, a more restrictive standard than it maintains at its northern border with the United States.

Along Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, in Tapachula, Yuriria Salvador, coordinator for structural change at the Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center, told the Intercept that new Mexican migrant interdiction deployments at the United States’ request are nothing new: “The response of the Biden administration is very similar to the response of the Trump administration.”

This reinforces Mexico’s role as an “interdiction state,” or “a buffer zone where enforcement activities are fluid and subject to geopolitical negotiation,” the Washington Post reports. Migration researcher Cris Ramón told the Post that Mexico’s role increasingly looks like that of Turkey, which has received material and diplomatic benefits from Europe by serving as a buffer for Syrian refugees. “In both cases you’re externalizing your borders and making another nation your border authority.”

An increasing number of migrants are deciding to seek asylum in Mexico, where the government’s refugee agency (COMAR) reports receiving 31,842 asylum requests during the first four months of 2021. That sets COMAR on pace to shatter its 2019 record of 70,422 asylum requests. (As recently as 2015, COMAR only received 3,424.) Nearly half of COMAR’s 2021 asylum seekers are from Honduras, followed by citizens of Haiti, Cuba, El Salvador, Venezuela, and Guatemala.

Disturbingly, migrant advocates in Tapachula told the Intercept that Mexico’s National Guard and migration enforcement agency (INM) may have begun carrying out sweeps outside COMAR’s offices during early-morning hours, detaining and presumably deporting undocumented asylum seekers as they begin queueing to fill out applications.

The U.S. National Security Council’s director for the Western Hemisphere, Juan González, told the Post that the Biden administration’s migration agenda with Mexico goes well beyond personnel deployments. “Yes, we talk about enforcement, but also about support for humanitarian programs, addressing the root causes of migration and promoting economic investment.”

Still, reporters Nick Miroff and Mary Beth Sheridan assert that U.S. officials’ dependence on Mexico to crack down on Central American migration, which reduces political pressure at the border, gives Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador leverage to push for U.S. concessions on other priorities. These may include abstaining from criticism of AMLO’s security policies or recent anti-democratic political maneuvers.

Luis Rubio of the México Evalúa think tank told the Post that a basic premise of the bilateral relationship “that dated back to the 1980s” held that the U.S. and Mexican governments would discuss different issues—trade, drugs, migration—as separate items. That way, “a dispute in one area wouldn’t contaminate the entire relationship.” By demanding cooperation on migration in exchange for concessions in other areas like trade or democracy, Rubio argues, Donald Trump undid that “separate lanes” tradition. That in turn allows AMLO to seek concessions on other issues in exchange for helping to push back migrants, including asylum seekers.

Miroff and Sheridan note, though, that a sharp recent increase in arrivals of Mexican single adult migrants could diminish some of López Obrador’s potential leverage.

Links

- In what it calls a “trial balloon,” the Biden administration’s Interagency Task Force on the Reunification of Families reunited four deported migrant parents with children whom the Trump administration had separated from them in 2017 and 2018. The plan is eventually to reunify, in the United States, over 1,100 families who remain separated, from an overall total of about 5,500 separations. Deported parents still haven’t been located for at least 445 separated children in the United States. At the New Yorker, Jonathan Blitzer recounts the end of a Honduran mother’s long wait to be reunited with her teenage sons after Border Patrol separated them in 2017.

- A 40-foot boat carrying 30 undocumented Mexican migrants and one undocumented Guatemalan migrant ran aground and broke up off of San Diego’s Cabrillo National Monument on May 2. Three migrants drowned, the rest are in U.S. government custody, and the boat’s U.S. citizen pilot is facing criminal charges. “Many of the passengers told authorities that they paid $15,000 to $18,000 to be smuggled into the United States,” the San Diego Union-Tribune reported. “The Border Patrol tallied 1,273 smuggling arrests on the California coast during the 12 months that ended Sept. 30, a 92 percent increase from the same period a year earlier,” according to AP. “Since Oct. 1, it has made more than 900 arrests.”

- “Currently, the plan is for me to travel to Mexico and Guatemala on June 7 and 8th,” said Vice President Kamala Harris. She is scheduled to have a conversation with Mexican President López Obrador on May 7. This will be her second meeting with AMLO. At a Council of the Americas event, Harris discussed plans for assistance to Central America to address “acute causes” and “root causes” of migration. “If corruption persists, history has told us, it will be one step forward and two steps back,” she said.

- A challenge to those plans occurred on the evening of May 1 in El Salvador, as a newly seated legislative supermajority immediately fired independent high court justices and the chief prosecutor. “Just this weekend, we learned that the Salvadoran Parliament moved to undermine its nation’s highest court. An independent judiciary is critical to a healthy democracy and a strong economy,” Vice President Harris warned.

- At Vox, Nicole Narea questions whether “root causes” aid actually reduces migration, noting studies that have found most migrants from Central America, while poor, have some resources and tend not to be among the region’s poorest.

- The Biden administration officially canceled border wall construction projects paid for with money that Donald Trump, declaring a national emergency, had drawn from the Defense Department’s budget. This money was to build about 466 miles of wall, of which about 123 remained unbuilt when Donald Trump left office. Documents seen by WOLA indicate that of $9.9 billion in money taken from the Defense Department, about $3.5 billion remains unspent, of which perhaps $1.4 billion would go to contract termination and suspension costs. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) also announced it would use funds to repair Rio Grande levees damaged by wall construction in Texas, and to undo soil erosion damage caused by wall-building in San Diego.

- At Roll Call, moderate Senate Democrats Robert Menendez (D-New Jersey) and Mark Kelly (D-Arizona) voiced support for the Biden administration’s plan to provide CBP’s infrastructure account with $1.2 billion in 2002 for facilities and technology—but not for border walls. “[W]e need to have area vehicles, satellite, the ability to interface with Border Patrol and Customs, and so I’m open to whatever it is. We’re not building a wall,” Menendez said.

- Two investigations by the Intercept, about anti-drone measures and harvesting data from cars’ onboard computers and mobile phone links, raised concerns about how providing CBP with new border technologies “could lead to further surveillance and militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border.”

- A strong Washington Post editorial calls ICE “The Super Spreader Agency.” It contends that because the agency ignored foreseeable “red flags” about the spread of COVID-19 in its mostly privately run detention centers, “Nearly 13,000 detainees have tested positive—likely an undercount of the virus’ real spread—and at least nine have died.”

- A Pew Research Center poll found 68 percent of adult U.S. respondents saying the government is doing a very bad or somewhat bad job of dealing with increased numbers of asylum seekers at the border; 47 percent “say it is very important to reduce the number of people coming to the U.S. seeking asylum; another 32% say this is somewhat important.” A University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll found a first-place tie among Texas voters: 16 percent ranked the pandemic as the top issue facing the state, and 16 percent chose immigration and border security. A Civiqs poll commissioned by the Immigration Hub found “57 percent of Americans accept illegal immigration when the immigrants are fleeing violence in their home countries,” but the number falls to 46 percent when the cause is poverty or hunger, 36 percent for family reunification, and 31 percent for job-seeking.

Dozens of U.S.-bound Haitian migrants were stuck for weeks in Honduras because the government is demanding they pay US$190 each to obtain exit visas after entering the country irregularly, reports the Honduran outlet ContraCorriente.

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson