With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here. (Subsequent updates will go in-depth into Vice President Harris’s planned visit to the border this Friday, as reported by media on June 23).

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

July migration appears to be exceeding June

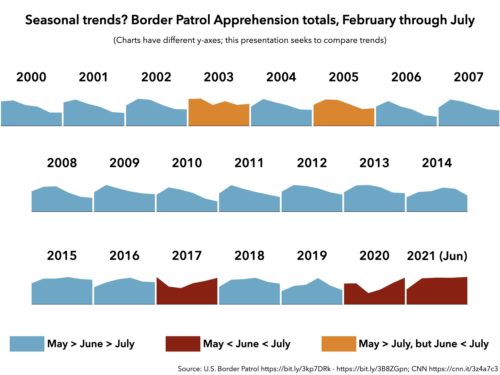

Only twice in this century has migration at the U.S.-Mexico border been greater in the summer than in the spring. On both of those occasions, migration was recovering from a sharp drop earlier in the year: after the January 2017 inauguration of Donald Trump, and after the March 2020 imposition of COVID-19 travel restrictions.

2021 appears to be the first time this century that summer migration may exceed spring without an early-year reduction, despite the harsh heat along most of the border during the season’s height. This was foreseeable, as COVID-19 has devastated economies, border closures had stifled migration, and travel restrictions worldwide are gradually lifting. Still, in the past 22 years for which we have monthly data, we have not seen this pattern before.

Border Patrol’s encounters with migrants in July are “projected to be even higher” than June, according to preliminary data shared with the Washington Post. This past week, reporting about the summer increase has focused on Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Rio Grande Valley sector, the easternmost segment of the border, in south Texas. (CBP divides the U.S.-Mexico border into nine sectors.) There, Border Patrol Sector Chief Brian Hastings tweeted on July 25 that agents had apprehended more than 20,000 “illegally present migrants” during the previous week alone.

As of July 26, Border Patrol was holding about 14,000 migrants in its stations and processing facilities border-wide, the Rio Grande Valley Monitor reported. On the 25th, in the Rio Grande Valley, the agency was holding 7,000 migrants, up from 5,000 on July 19 and 3,500 on July 14. Border Patrol facilities’ capacity in the sector is about 3,000.

As of July 28, 2,246 of those in Border Patrol custody were unaccompanied children, up from 724 on July 12. This number of children in the agency’s rustic, jail-like facilities rarely exceeded 1,000 in June. That month, as the law requires, Border Patrol agents were able to move kids within 72 hours into shelters run by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). As of June 30, children were spending an average of 28 hours in CBP custody; the stay is almost certainly longer now.

This is due to a steady increase in arrivals of unaccompanied children, to levels not seen since late March. Border Patrol encountered an average of 501 children per day between July 25 and 28, and 547 per day the previous week. We had not seen an average over 500 since March 23-25, the first few days for which CBP and HHS started providing daily numbers of unaccompanied children.

Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol agents are apprehending large groups of kids, adults, and families all at once. On July 27, agents encountered a single group of 509 people, mostly families and unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Venezuela. It was the largest group encountered all year. Along the Rio Grande, where periodic flooding and currents make it impossible to build fencing on the water’s edge, migrants who want U.S. authorities to apprehend them gather on the riverbank south of the border fence. Once on U.S. soil, they have the right to ask for asylum or other protection in the United States.

Migrant detention and processing duties have strained Border Patrol personnel to the extent that the agency was contemplating shutting down some interior highway checkpoints—a move that requires approval from CBP headquarters in Washington, which has not been forthcoming, the Monitor reported.

The large numbers have also strained capacities at the Rio Grande Valley’s largest humanitarian respite center, the Catholic Charities facility in McAllen, Texas. The respite center gives asylum-seeking migrant families a place to be—instead of out on McAllen’s streets—between their release from CBP custody and their travel to destinations elsewhere in the United States, where immigration courts will adjudicate their cases.

Late on July 26, the respite center had to close its doors to new migrants, as it had hit its 1,200-person capacity. Sister Norma Pimentel, the executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, said she had to ask Border Patrol “to hold drop-offs to give us a chance to have space.” Still, agents kept dropping new busloads of migrants off on the street outside, and other area churches took in several hundred people. By July 28, Pimentel told the Monitor, the shelter was no longer at capacity.

Richard Cortez, who serves as county judge in Hidalgo—one of the Rio Grande Valley’s three counties, which includes McAllen—called on the federal government to “stop releasing these migrants into our communities” and on the governor of Texas to allow him to reinstate a mask mandate and other COVID-19 measures. “It was manageable last week, we did not have problems at all that I was aware of,” Cortez said on July 27. “Now, my understanding is that the Catholic Charities—who was taking over the responsibility of testing the immigrants, isolated them if they tested positive, they put them in the hospital if they were very sick…reached their capacity. So now there’s no buffer between the federal agencies and us.”

In June, the Rio Grande Valley accounted for one-third of Border Patrol migrant encounters along the border, and 56 percent of all encounters with child and family migrants. We don’t know yet whether Border Patrol’s other eight sectors are seeing a similar July increase in migration, though Tucson, Arizona, the fourth-busiest sector in June, has also begun to register large groups.

Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas), whose district stretches along the border from Laredo nearly to McAllen, told Axios that, between July 19 and July 26, Border Patrol had released 7,300 migrants in the Rio Grande Valley sector without specific dates to appear in immigration court. In order to cut processing time, agents are issuing a document that instructs migrants to report to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office within 60 days, at which point their asylum or protection processes will begin. Officials told the New York Times that about 50,000 of these “notice to report” documents have been issued to migrants since March 19. Axios noted that just 6,700 have reported to ICE offices so far, while 16,000 have not shown up within the 60-day reporting window. About 27,000 more haven’t hit the deadline yet. In many cases, no-shows may owe to migrants’ confusion about the process.

Republican senators raised this “notice to report” issue to Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, who testified at a July 27 hearing of the Senate Homeland Security Committee. The Secretary’s testimony coincided with the White House’s release of a fact sheet laying out a “Blueprint for a Fair, Orderly and Humane Immigration System.” That document, which contained little new information, declares, t “We will always be a nation of borders, and we will enforce our immigration laws in a way that is fair and just. We will continue to work to fortify an orderly immigration system.”

With an increase in migration, and the “Title 42” pandemic border policy (discussed below) making it harder to seek asylum, more migrants are traveling through dangerous sections of the border zone where, by Border Patrol’s conservative estimates, 8,258 people have been found dead of dehydration, exposure, and other causes since 1998. (See our July 16 update for a fuller discussion of migrant deaths.) In the Big Bend sector wilderness of west Texas, Border Patrol has found 32 remains of migrants so far in fiscal 2021, way up from 15 in all of 2020 and far more than the sector’s prior high of 10 (2018).

More migrants appear to be on their way, as COVID-19 travel restrictions begin to relax worldwide. Right now, at least 9,000 northbound migrants from Haiti and several other countries are stranded in the town of Necoclí, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. They aren’t being blocked: it’s just that their numbers have overwhelmed the ferry service that takes them to the opposite shore of the Gulf of Urabá, where they cross into Panama. Colombia lifted its pandemic border closures in May, and migration numbers jumped soon afterward.

Title 42 is not being lifted for families

Our July 6 update, which reflected media reporting at the time, noted that the “Title 42” pandemic measure “may be in its last days,” at least for migrant families. While no official had confirmed it, reporting indicated that Title 42 would stop applying to families by the end of July. That is not going to happen: the administration, citing concern over new COVID-19 variants and rising overall numbers, will continue to expel protection-seeking families.

Title 42 is the name given to an old law that the Trump administration’s Center for Disease Control (CDC) invoked, in March 2020, to rapidly expel nearly all migrants encountered at the border back to Mexico or their home countries, usually without a chance to ask for asylum. Most citizens of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras get expelled into Mexico, as do migrants from other countries who have tourist visas or other migratory status in Mexico.

The Biden administration kept Title 42 in place, though it has not applied it to unaccompanied children and rarely applies it to those who can’t easily be expelled to Mexico. Fewer family members have been expelled in recent months—16 percent of all who were encountered in June—in part because Mexico’s border state of Tamaulipas is refusing expulsions of families with small children, and in part because since May, nearly half of families have come from countries other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras.

While the COVID-19 virus’s Delta variant is a key factor leading the CDC to prolong Title 42, two U.S. officials told NBC News that the Biden administration is also “concerned about funding, facilities and staffing issues associated with lifting the restrictions.” Six months in, the administration still lacks capacity to process large numbers of asylum seekers, enroll them in alternatives-to-detention programs, and adjudicate their protection claims.

“If CDC is going to continue with Title 42, they need to be prepared for a lawsuit and to answer very specific questions in a deposition about whether they genuinely believed there was no way to process asylum seekers safely,” ACLU attorney Lee Gelernt, who has led an ongoing lawsuit against Title 42’s application to families, told the Washington Post.

A July 28 report by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) disputes CDC claims that there is any public-health justification for expelling migrants. “Every aspect of the expulsion process, such as holding people in crowded conditions for days without testing and then transporting them in crowded vehicles, increases the risk of spreading and being exposed to COVID-19,” it reads. PHR researchers’ interviews with 28 expelled asylum seekers told of suffering “gratuitously cruel” treatment and family separations at the hands of Border Patrol agents, and assault, kidnapping, extortion, and sexual violence, along with shakedowns from Mexican authorities, after being expelled into Mexico.

On the night of July 26, DHS announced that it would resume applying “expedited removal” to migrant families who are not expelled under Title 42. As many family members as possible who don’t express fear of returning will be flown back to their home countries very quickly. Those who do express fear, in many cases, may be held in CBP custody until they can get fast-tracked “credible fear” interviews with asylum officers. (According to the 1997 Flores Settlement agreement, as revised, families with children cannot be held in custody for more than three weeks.)

Those who pass these interviews will likely be released with dates to appear in immigration court. Those who do not will be deported. A current and a former official told the Washington Post that deported families will be flown “back to Central America using the Electronic Nationality Verification program, which relies on biometric data to identify migrants who lack identification or travel documents.”

The expedited removal decision caused an outcry among rights advocates. “Jamming desperate families through an expedited asylum process would deny them the most basic due process protections and can hardly be called humane,” the ACLU’s Gelernt told the New York Times.

In an agreement with ACLU and plaintiffs in the ongoing suit against Title 42’s application to families, DHS had been permitting about 250-300 expelled family members considered “most vulnerable” to re-enter the United States from Mexican border towns to pursue their asylum petitions. However, CBP officials in San Diego started cancelling these appointments late during the week of July 18, citing capacity issues at the port of entry. Attorneys at Al Otro Lado, an organization that assists migrants in Tijuana and San Diego, said that several of their clients ended up homeless in Tijuana after CBP abruptly canceled their appointments.

Texas governor’s crackdown threatens to snare humanitarian workers

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R), who has already declared an “emergency” in some counties, hosted Donald Trump at the border, and sought to build segments of state border wall, continues to push back hard against migration.

As of July 29, his state was jailing 55 migrants, arrested on trespassing charges, in the Briscoe prison in the town of Dilley, between Laredo and San Antonio. That’s up from three on July 20. The Briscoe facility can hold more than 950 people; all of those jailed so far have been single adult men.

On July 27 Abbott expanded powers of Texas National Guard personnel whom he has deployed to the border, giving them the ability to arrest civilians. It is very unusual in the United States for military personnel to be empowered to carry out arrests on U.S. soil, a circumstance usually limited only to riots and insurrections, and then only for a brief time.

(Other states with Republican governors have sent small contingents of guardsmen or police to the border in response to a call from Abbott. On July 26 South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem (R), who controversially is paying for her state’s Guard deployment with a private donor’s money, gave remarks in front of a section of border wall behind a Whataburger fast-food restaurant near the Hidalgo-Reynosa border bridge. Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) defended a two-week deployment of state police as “the right thing to do” and said she wanted to renew it. Elsewhere, Nebraska state troopers returned from a 24-day tour affected by the desperate conditions of the children and families they encountered.)

On July 28 Gov. Abbott upped the ante, issuing an order prohibiting anyone except law enforcement personnel from transporting migrants who “pose a risk of carrying COVID-19 into Texas communities.” As a result of this order, if personnel from Texas’s Department of Public Safety (presumably through profiling) suspect that a civilian vehicle is transporting migrants released from CBP custody, they may reroute the vehicle to its place of origin and impound it.

This order falls heaviest on humanitarian workers: those, like volunteers at Sister Norma Pimentel’s Catholic Charities respite center, who need to transport asylum seekers to airports, overflow facilities, or quarantine hotels. It is unclear whether Abbott’s order would apply to Greyhound and other bus companies that transport migrants from border towns to their destinations elsewhere in the United States. “I assume, if you’re Greyhound or somebody that’s transporting people from the respite center on behalf of Sister Norma, (they’re) going to be prohibited from doing that,” Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas) told the Rio Grande Valley Monitor.

Abbot issued his order as Rio Grande Valley counties are recording some of their worst infection numbers in months, as the Delta variant spreads. Still, as of mid-July the COVID-19 test positivity rate for migrants was below that of Texans as a whole, and more than 85 percent of migrants are reportedly getting vaccinated upon release. In one example of how humanitarian organizations are screening migrants for COVID-19, the Catholic Charities respite center in McAllen performs COVID-19 tests on all migrants whom CBP drops off at its doors, at the expense of the McAllen city government. Additionally, Catholic Charities is paying more than 10 area hotels to house migrants who must be quarantined if they test positive. The respite center’s executive director has said that about 1,000 people are currently being housed in hotels—not all are COVID-positive, but some members of their family groups are—where they are required to stay, with volunteers delivering food and other needs, until they test negative.

On July 29 Attorney General Merrick Garland sent a letter to Gov. Abbott demanding that he reverse his transportation order, calling it “both dangerous and unlawful.” It notes, “The Order violates federal law in numerous respects, and Texas cannot lawfully enforce the Executive Order against any federal official or private parties working with the United States.” Garland promises that the Justice Department will “pursue all appropriate legal remedies to ensure that Texas does not interfere with the functions of the federal government.”

Links

- A Mexican federal court has temporarily stayed municipal authorities’ order to evict the 14-year-old Senda de Vida shelter, the largest in Reynosa, Tamaulipas. Citing Rio Grande waterway requirements, the mayor’s office had given the shelter and its 600 occupants days to vacate the site, in one of Mexico’s most dangerous border cities.

- A Mexican man died of head injuries after falling from a new 30-foot segment of border wall in Otay Mesa, just east of San Diego, on July 25.

- A second Government Accountability Project whistleblower complaint includes new revelations of deplorable conditions at the private contractor-managed HHS emergency child migrant shelter at Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, Texas. Conditions included “riots” in boys’ tents, children cutting themselves, hundreds of COVID cases, and severe shortages of basic goods like face masks and underwear. One mental health clinician reportedly told a boy “he had nothing to complain about and that, in fact, he should feel grateful for all he was being given.”

- Another report from the DHS Inspector General finds serious deficiencies in border and migration agencies’ attention to detainees’ medical needs. “Once an individual is in custody,” it finds, “CBP agents and officers are required to conduct health interviews and ‘regular and frequent’ welfare checks to identify individuals who may be experiencing serious medical conditions. However, CBP could not always demonstrate staff conducted required medical screenings or consistent welfare checks for all 98 individuals whose medical cases we reviewed.“

- DHS announced it is canceling contracts to use 2020 Homeland Security appropriations money to build about 31 miles of border wall in and near downtown Laredo, Texas. The Trump administration’s wall-building project had been bitterly opposed by local leaders. A year ago, the city council had unanimously approved the painting of a giant “Defund the Wall” mural on a main street.

- The White House issued a document outlining its strategy for addressing the root causes of migration in Central America, as foreseen in a February 2 presidential executive order. It covers cooperation on economic issues, corruption and governance, human rights, preventing criminal violence, and preventing domestic, sexual, and gender-based violence.

- The Washington Post’s Kevin Sieff profiles Eriberto Pop, a Guatemalan lawyer working to track down parents whom the Trump administration separated from about children. About 275 parents remain to be located. This involves a lot of riding a motorcycle around remote areas of Guatemala’s rural highlands.

- El Diario de Juárez documents the experience of migrants from Ecuador, about half of whom have been encountered across from Ciudad Juárez in Border Patrol’s El Paso sector. “According to the Ecuadorian migrants themselves, the ‘coyoteros,’ as they call human smugglers in that country, fly them as tourists to Mexico City or Cancun, from where they are taken to Ciudad Juarez.”

- ProPublica’s Dara Lind finds that ICEprosecutors are still seeking maximum deportations in immigration court, ignoring Biden administration guidance “to postpone or drop cases against immigrants judged to pose little threat to public safety.”

- House of Representatives Republican leadership introduced legislation that would restore much of the Trump administration’s border and migration policies, including a restart of border wall construction.

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson