With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Last week’s Update noted that seven citizens of Nicaragua had died crossing the Rio Grande, in five separate incidents over about six days. This week, the grim toll continued to rise.

Three more Nicaraguan citizens perished in the river over the Memorial Day weekend, according to Nicaraguan Texas Community, a non-profit organization. Kelvin Antonio Tórrez Medina’s body was identified in Laredo, Texas, on May 27. The bodies of Alexander Zelaya Espinoza and Iván Ramiro Rivera Velásquez were recovered in Piedras Negras, Mexico, across from Eagle Pass, Texas, on May 28 and 29, respectively.

“Between March 4 and May 19, 2022, more than 20 Nicaraguans have perished,” reports Confidencial, an independent Nicaraguan media outlet that persists despite repression from the regime of President Daniel Ortega. “Of these, nine died trying to cross the waters of the Río Bravo [Rio Grande], mainly in the Piedras Negras area.”

Another migrant of unknown nationality drowned on May 31 at California’s Border Field State Park, trying to swim around the border fence that continues for about 100 yards into the Pacific Ocean. CBP meanwhile posted a release about the death of a man who fell from the border wall in Tornillo, Texas on March 27. As documented in recent reports from the Journal of the American Medical Association and the Washington Post, the number of people dead or gravely injured from attempts to climb the border wall has multiplied since the Trump administration installed hundreds of miles of 30-foot fencing.

In mid-Texas’s Del Rio Sector alone, Border Patrol’s sector chief reported 10 deaths in a May 31 “Weekend Rewind” tweet.

In Tijuana, scores of people attended a June 2 funeral for two Haitian migrants: EFE identified them as “Joselyn Anselme, 34, who was killed in an attempted assault, and Caroly Archangel, 30, who died of a heart attack due to alleged medical malpractice.”

Border Patrol found the remains of more than 8,600 migrants on U.S. soil between 1998 and 2021. Humanitarian groups that recover bodies in specific regions routinely find far more than Border Patrol reports.

In a year that may break records for overall migration, it is not surprising that the number of migrants dying may be approaching record numbers. But the problem is exacerbated by the Title 42 pandemic policy’s closure of ports of entry to asylum-seeking migrants. Media reports point to many children and parents among the dead as they attempt to cross between the ports of entry, which used to be rare. Two small children are among the ten Nicaraguans recovered from the river this month.

Border Patrol is slow to report migrant deaths along the entire border: it has still not shared an official figure for 2021. When it does so for 2022, it’s probable that, even amid a rise in migration, the ratio of deaths to overall migrant encounters may be greater than normal.

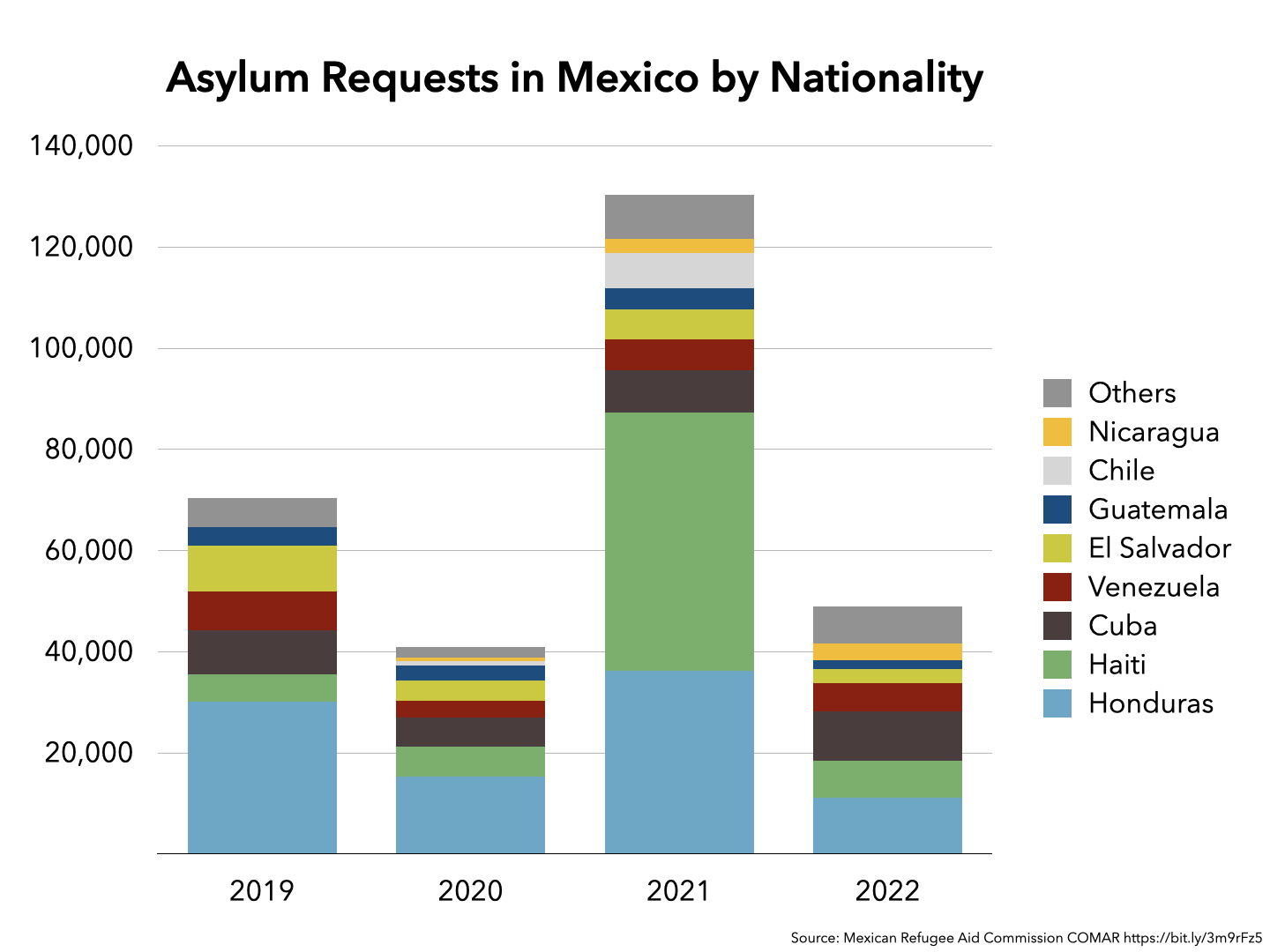

The Mexican government’s Refugee Assistance Commission (COMAR) has published data documenting migrants’ applications for protection in Mexico’s asylum system through May 31. In the first five months of 2022, 48,981 citizens of other countries have filed asylum requests with COMAR.

That is already the third-largest annual total for Mexico, which as recently as 2013 got only 1,296 asylum requests all year. COMAR is on pace to finish 2022 with its second-largest number of asylum requests, after 2021 when a large number of Haitian migrants helped lift the total over 130,000. (However, new asylum applications have declined for the past two months, from 13,238 in March to 9,113 in May.)

This year, Haiti is not the number-one country of origin of Mexico’s asylum applicants. It is third behind Honduras (usually the number-one country) and Cuba, and followed by Venezuela, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Brazil (including many children of Haitian parents), Senegal, and Colombia.

The Mexican Interior Department’s Migratory Statistics Unit has updated data through April. That month saw Mexico’s migration authorities apprehend their fifth-largest monthly number of migrants ever: 30,980 people, which is in fact fewer apprehensions than Mexico measured in August, September, and October of 2021.

Half of migrants apprehended in Mexico in April were not from El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. Instead, many are from (in declining order) Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Haiti, Chile (mostly children of Haitian parents), and Peru. This is a sharp break with past years, when a quarter or fewer of Mexico’s migrant apprehensions were citizens of these “other” countries.

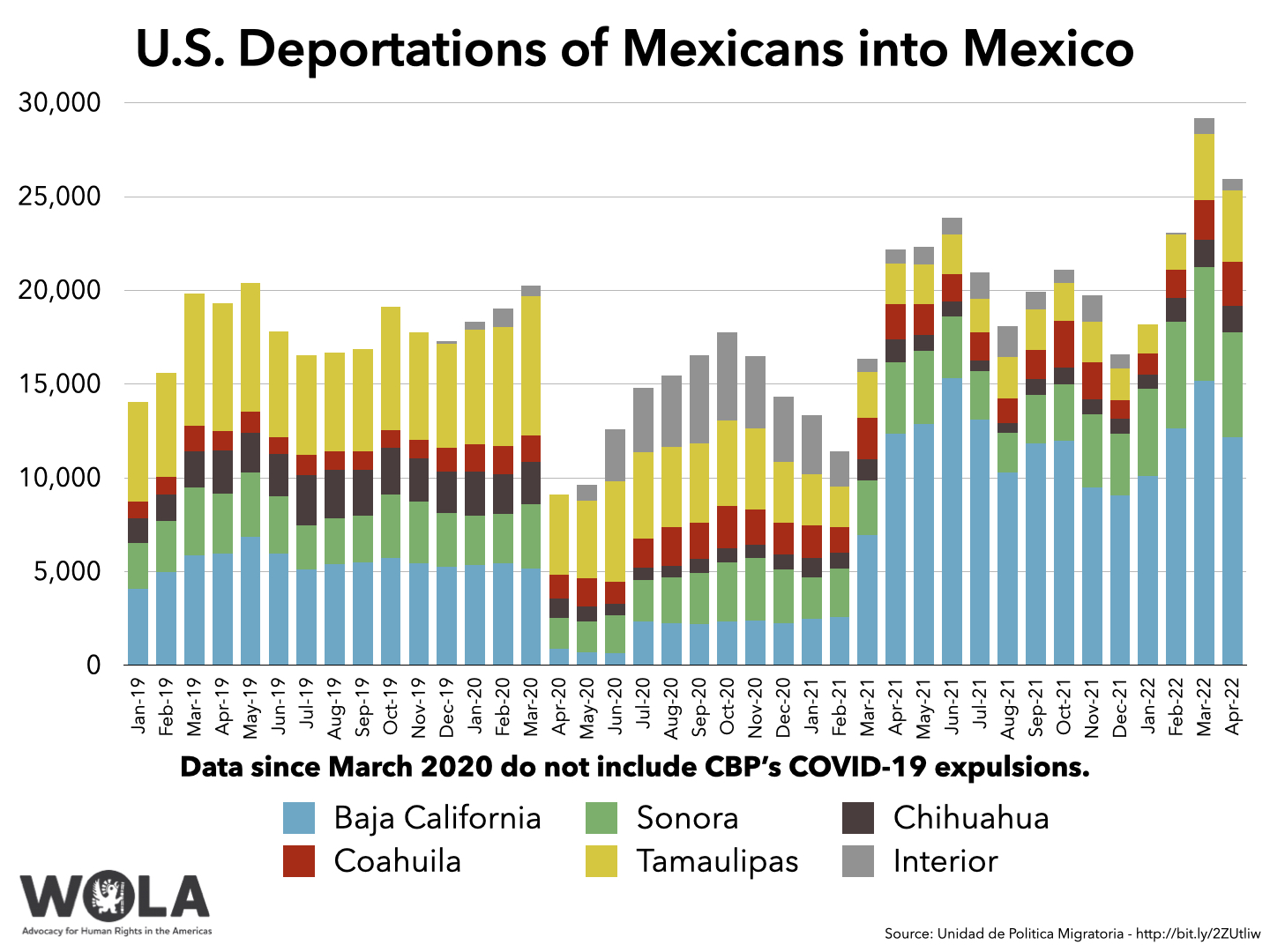

Mexico’s data also show an increase in the U.S. government’s deportations of Mexicans into Mexico. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported 25,966 Mexican citizens in April, the second-highest monthly total (after March) since 2019. (This figure does not include Title 42 expulsions into Mexico, which often happen at the borderline without any Mexican authorities on hand to count them.)

April deportations to the Mexican border state of Tamaulipas (3,804), where organized crime activity and kidnapping are so severe that the State Department has issued a level-four “Do Not Travel” warning, hit their highest level since November 2020.

Presidents and heads of government from many Latin American and Caribbean countries will be in Los Angeles on June 8, 9, and 10 for the ninth Summit of the Americas, the latest in a series of high-level region-wide meetings that began in 1994. Five issues lead the agenda, White House and State Department officials explained to reporters on June 1: “democratic governance, health and resilience, the clean energy transition, our green future, and digital transformation.”

“On the margins of the summit,” National Security Council Western Hemisphere Director Juan González explained, will be an additional item: “addressing the historic migration crisis.” President Joe Biden is to “join other heads of state to sign a migration declaration, sending a strong signal of unity and resolve to bring the regional migration crisis under control.”

Though the U.S. political debate tends to focus on what happens at the U.S.-Mexico border, much of the hemisphere is also experiencing mass emigration, receiving large-scale immigration, or in some cases both. Over 6 million Venezuelan migrants have relocated to Colombia and elsewhere in South America. Nicaraguans fleeing the Ortega regime have arrived massively in Costa Rica. Mexico’s asylum system, as noted above, is facing unprecedented demand, much of it from Central America, Haiti, and Cuba. Haitians are crossing into the Dominican Republic or attempting dangerous sea voyages. (For more on the hemisphere-wide migration phenomenon, see WOLA’s May 26 commentary “Beyond the U.S.-Mexico Border.”)

Though the content of the Summit’s migration declaration isn’t yet known, U.S. officials are signaling a desire for greater shared responsibility at a time of very high migration throughout the region.

“For the last couple of months the President has and the Secretary of State and Secretary of Homeland Security, the Vice President, and others have been all-hands-on-deck to mobilize leaders around a bold new plan centered on responsibility sharing and economic support for countries that have been most impacted by refugee and migration flows,” González told reporters. “What we are hoping to do is…to look at the regional challenge from the context of responsibility sharing and the need to provide economic support to countries to have been impacted by refugee and migration flows, but also the importance of…in-country processing avenues, expanding refugee protections, and also addressing, I think, some of the core drivers of migration, which are lack of economic opportunities and insecurity.”

Brian Nichols, the assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, added that the summit’s migration declaration is likely to cover helping and “stabilizing” communities that are hosting migrants; ensuring access to legal documentation and public services; “promoting pathways for legal, orderly migration when appropriate”; ensuring ethical employment practices; “promoting humane migration management; and a shared approach to mitigating and managing irregular migration.”

It’s not clear how officials are squaring these goals and values with the court-ordered persistence of the Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy, which has returned nearly 2 million migrants into Mexico, Haiti, or elsewhere, usually with minimal coordination with local authorities and without giving threatened migrants a chance to ask for protection in the United States.

Sixteen members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus sent a letter to President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken urging them to include a list of commitments in the Summit’s migration declaration. These include, among others, protecting the rights of migrant children and other vulnerable populations; guaranteeing migrants’ access to medical care and legal counsel; ending detention for children and families; upholding the principle of non-refoulement (not sending endangered people back to places where they are threatened); and expanding safe and legal, pathways to migration.

In an essay at Foreign Affairs, Dan Restrepo of the Center for American Progress—who held González’s National Security Council post during Barack Obama’s first term—calls on U.S. policymakers to recognize that high levels of region-wide migration are “not going to stop.” Adjusting to that reality, he argues, will require “a new, hemisphere-wide approach to migration, combined with steps to modernize U.S. laws, policies, and border infrastructure.”

A sustainable migration framework for the Western Hemisphere must help integrate and establish legal status for already dislocated populations, with additional protection measures for the most vulnerable among them. It must provide options for would-be migrants apart from overburdened asylum systems. And it must establish infrastructure to respond to sudden increases in irregular migration. Large numbers of people will be moving throughout the Americas for years to come. It is time the United States coordinated more closely with other countries in the region to make this a manageable trend, rather than a disruptive one.

Investigations at the New York Times and Vice profile BORTAC, Border Patrol’s elite 250-member SWAT-team-like tactical unit, whose personnel killed the gunman in Uvalde Texas’s Robb Elementary School on May 24.

Border Patrol may operate within 100 miles of a land or coastal border, or elsewhere in a declared emergency. As one of the few non-military federal law enforcement bodies with “special operations” capabilities, BORTAC has played numerous non-traditional, non-border-specific roles.