AP Photo/Fernando Vergara

AP Photo/Fernando Vergara

The United States will host and chair the ninth Summit of the Americas the week of June 6, 2022, in Los Angeles, California. The Summit will focus on “Building a Sustainable, Resilient, and Equitable Future” and while migration is not an announced theme, it is expected to be a central topic of discussion. In the lead up to the Summit, the Biden administration has been negotiating bilateral arrangements on migration and protection with individual governments in the region, and plans to sign a hemispheric declaration on this issue during the Summit.

The administration’s focus on migration at the Summit reflects the reality facing the region. In recent years, we have seen changes in demographics, routes, and destination countries for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. In the past decade, Darién Gap crossings have increased significantly, migration to Latin American countries from within and outside the continent has increased, and the people arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border are no longer predominantly single adults from Mexico and Central America. In response to migration flows, governments in Latin America and the U.S. have been shifting their policies and practices through new visa requirements, border security and enforcement efforts, cooperation to address the root causes of migration, humanitarian assistance, and programs focused on protection and other legal pathways. Ahead of the Summit, WOLA and partners developed guiding principles for a regional framework on migration and protection in the Americas.

Given the dramatic shifts in the dynamics of migration to, from, and through the Western Hemisphere, WOLA examines below recent trends in human mobility and the challenges migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers face beyond the Mexico-U.S. border.

Migration trends in the Western Hemisphere have changed significantly over the past decade. Human mobility has increased in recent years throughout Latin America—driven by countries in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa. Intraregional migration (migration from one country to another within the region) has also been a common trend. Mexico and countries in Central and South America have served as sending, receiving, and transit countries.

A few key examples underscore the scale and instability of these important shifts. According to data published by the United Nations in mid-2015, almost 1 million Colombians fleeing the war and economic conditions had settled in Venezuela by that point in time. After the 2016 Colombian peace agreement was signed, many returned or migrated elsewhere due to Venezuela’s economic and political turmoil. Since the mid-2010s, more than 6 million Venezuelans have fled their country due to this turmoil and human rights violations. Over 5 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants have settled elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean, with more than half residing in Colombia and Peru. The magnitude of this displacement is second only to the war-driven Syrian refugee crisis.

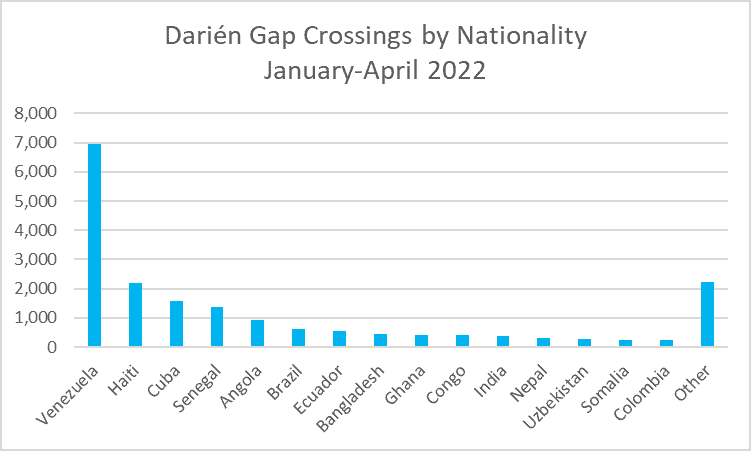

As WOLA previously illustrated, Darién Gap crossings between South and Central America were relatively low in the past decade (as low as 283 in 2011). The dangers of this forested, roadless, mountainous region deterred all but the most desperate migrants, but 2021 saw 133,726 crossings—a sharp increase from previous years. From January to April 2022 a total of 19,092 people crossed the Darién Gap; more than 3,000 were children. The top countries of origin for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers crossing the Darién Gap were Venezuela (6,951), Haiti (2,195), Cuba (1,579), Senegal (1,355), Angola (934), Brazil (606), Ecuador (561), Bangladesh (447), Ghana (400), Congo (394), India (372), Nepal (292), Uzbekistan (280), Somalia (254), and Colombia (252).

This data showcases that migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers from South America and beyond are increasingly willing to risk dangerous routes of transit. As WOLA has highlighted previously, several factors have prompted people to migrate in these high numbers, some of which include political and economic instability, insecurity, climate change-induced natural disasters and food insecurity, massive human rights violations, and precarious conditions exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: República de Panamá Gobierno Nacional. Irregulares en tránsito por Darién por país abril 2022.

2012 marked important shifts in the southern border of the United States as an increase in unaccompanied migrant children from Central America began to arrive; and in 2014, for the first time, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) registered more apprehensions of people who were not Mexican (many of whom were from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras).

In FY2021 (October 1, 2020 to September 30, 2021), 80 percent of migrants who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border were from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras (compared to about 95 percent 2016-2018). Although migration from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras northward from January-April 2022 was lower than what it was at that point in 2021, the numbers remain high, as more than 160,000 people from these countries were encountered at the U.S. southern border. 2021 saw a significant increase in encounters with migrants from other nationalities, which has persisted into 2022. In April 2022, 46 percent of CBP migrant encounters were with people from nationalities other than Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras, including over 35,000 Cubans, the second highest nationality after Mexicans.

2022 also saw a unique situation—a high number of Ukrainians fleeing to the U.S.-Mexico border, following Russia’s unprovoked aggression in February, clearly indicating how events beyond the Americas impact migration to the hemisphere and cause many countries to respond with extraordinary measures. Up until the U.S. implemented the Uniting for Ukraine program on April 25, which allows Ukrainians with a U.S. sponsor to stay temporarily in the country for a two-year parole, Ukrainian citizens were making their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. At the border, they were being processed for various forms of humanitarian relief and were exempt from the Title 42 border restrictions that have prevented hundreds of thousands of migrants from requesting protection in the United States since March 2020. With the new program in place, Ukrainians arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border no longer received special treatment, and many had to travel to Mexico City instead, where they are waiting to be admitted to the U.S. after submitting an application. Brazil and Argentina also introduced a special humanitarian visa for Ukrainian nationals, and other countries in Latin America have made immigration policy adjustments to accommodate the crisis in Ukraine.

The United States, while a common destination for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, is not the only recipient of people in transit in the Western Hemisphere. Countries in Latin America have served as transit and destination for people from other parts of the world.

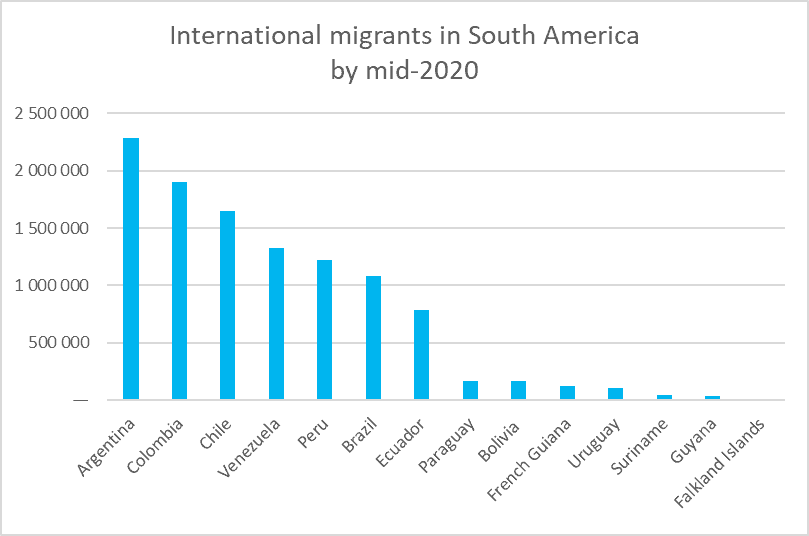

According to the International Organization on Migration’s data on Latin America, Colombia and Peru have been common destinations for Venezuelan migrants and refugees, while Argentina, Chile, and Brazil have been common destinations for migrants from other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and other continents in recent years. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs published estimates of the number of international migrants based in more than 200 countries in the world, relying on official statistics. The most recent numbers, covering the first half of 2020, showcased that in South America, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Venezuela, Peru, Brazil, and Ecuador were the destination countries with the highest number of international migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers while farther north, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Panama had the highest numbers.

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020). International Migrant Stock 2020.

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020). International Migrant Stock 2020.

More recently, we’ve seen the numbers for migration to the region from within and outside Latin America continue changing. While Costa Rica has historically been a destination for Nicaraguans, the numbers have dramatically increased since the Ortega government’s crackdown on protests that began in 2018 pushed human rights defenders, members of the opposition, ex-political prisoners, journalists, and others to flee. Costa Rican authorities processed close to 38,000 requests for legal status in 2021, with 16,423 receiving permanent or temporary residency in the country or another legal status. As of April 2022, there were over 1.8 million Venezuelans in Colombia and over 1.2 million in Peru.

The 2021 mid-year report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) indicated that Colombia hosted the most refugees in Latin America and was the second country to host the most refugees in the world (more than 1.7 million at that point, including Venezuelans). Colombia was also the country with the highest number of internally displaced people protected or assisted by the UNHCR. The report indicated that in the first half of 2021, the United States was the largest recipient worldwide of new asylum claims (72,900) and Mexico was the third (51,700). (By the end of 2021, Mexico had received 130,627 asylum requests.) In the first half of 2021, 39,300 Venezuelans, 33,900 Hondurans, 16,600 Haitians, 14,600 Nicaraguans, and 13,400 Guatemalans applied for asylum in a foreign country. In a troubling trend, pending applications from asylum seekers were higher by mid-2021 than they were at the end of 2020.

Countries in the region have adapted their policies to address migration flows. The response has been mixed, as some measures have focused on broadening protections and others on hardening enforcement.

In January 2022, Colombia created two new visa categories that allow nationals from Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru to apply for a two-year visa, with the opportunity to apply for permanent residency afterwards. Previously, in February 2021, Colombia also announced the government would offer temporary protective status to Venezuelans who reside in the country. The measure allowed Venezuelan migrants and refugees to apply for 10-year residence permits, facilitating access to medical services and employment opportunities. The policy shift, while a welcomed change, confronted challenges given the government’s limited capacity to process applications. In 2021, Peru began offering a Temporary Permanent Permit Card (CPP), an initiative that was extended in January 2022. In 2019, Brazil classified the situation in Venezuela as one where grave and generalized human rights violations take place, which simplified the right to seek refuge; this criteria has been extended until December 2022.

While good practices that prioritize the rights of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are not widespread, some other examples that adequately address their needs have included:

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered changes in border policies in 2020, as most countries in the region put in place partial or total border closures, followed by COVID-19 tests or proof of vaccination as entry requirements. Measures unrelated to public health have also been put forth by governments in the region in recent months.

In January 2022, Mexico began implementing new visa requirements for Venezuelans, including needing proof of economic means to qualify—a tall order since Venezuela is a country undergoing institutional decay and a complex humanitarian emergency. In the second half of 2021 Mexico also reinstated visa requirements for Ecuadorians and Brazilians. Previously in 2019, Mexico stopped issuing exit visas for some migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers including Haitians, Cubans, and migrants from Africa and Asia, which had previously allowed them to transit through the country on their journey north.

In order to deter migrants and asylum seekers from crossing through the Darién Gap, Panama tightened security measures along the border with Colombia in February 2022. Costa Rica announced earlier this year that it would begin implementing new visa requirements for Venezuelans, Cubans, and Nicaraguans. Ecuador had historically allowed visa-free travel for most nationalities, but it imposed new restrictions in 2019 and 2021.

Farther south, in February 2022, Chile put into effect a border law that tightened crossings at the Chile-Bolivia border, and then Chilean President Sebastián Piñera declared a state of exception that deployed the armed forces to the provinces that share a border with Bolivia and Peru. The Chilean government also announced plans to build another 300 meters of ditch along the border with Bolivia. This added on to earlier policies to restrict migration, such as requiring visas from Haitians starting in 2018. While the government of Chile’s new president, Gabriel Boric, has lifted the state of exception, his Minister of the Interior affirmed that the decree allowing for Chilean armed forces to be present at the border, as well as police forces and equipment for border security efforts, will remain in place. As of May 1, citizens of Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Dominica must also have a temporary visa to enter the country, which needs to be requested at Chilean consulates or embassies.

Cuban, Haitians, and Venezuelans face some of the harshest visa restrictions in Latin America. According to official government records, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Chile, Brazil require a visa or tourist card for people from Cuba, Haiti, and Venezuela. (Some do allow people from these nationalities to remain in the country for a period of 30-90 days without a visa.)

Stricter enforcement measures on human mobility do not halt migration. They instead push migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers toward underground routes that expose them to crimes and human rights violations. Some people are particularly vulnerable to violence, including Black migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers confronting more overt racism and xenophobia, women facing gender-based violence, LGBTQ+ individuals, people with disabilities, and people who face language barriers in transit (such as Indigenous people from Latin America or migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers from other continents).

People in transit face dangers throughout Latin America. The Pisiga-Colchane region of the Chilean-Bolivian border, a high-altitude desert known for its harsh, often deadly weather conditions, has seen an increase in smugglers who charge migrants high prices. Migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers crossing the Venezuela-Colombia border are exposed to theft, violence, and being recruited by armed or narcotrafficking groups. Farther north, the organization Doctors Without Borders has documented that people in transit in recent months have confronted longer (and therefore, more expensive) journeys through the Darién Gap. This has increased their exposure to assault and sexual violence (as of May 2022 Doctors without Borders had treated 89 patients there who had experienced of sexual violence). As WOLA has reported, migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in transit throughout Mexico and those returned to Mexico by the United States are exposed to human rights violations. According to a 2022 report from Jesuit Services for Migrants (Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes México), 2021 saw a 292 percent increase in reports of migrant disappearances in Mexico.

In advance of the Summit of the Americas, the Biden administration has been working on a hemispheric declaration on migration and protection addressing “shared principles for a collaborative, coordinated response to migration and forced displacement” that is expected to be adopted at the Summit. Prior to the Summit, the administration has been working to reach bilateral arrangements with individual governments. In March 2022, the U.S. signed a joint Migration Arrangement with Costa Rica that outlined mutual commitments on migration and protection. During the April 2022 trip that Secretary Blinken and Secretary Mayorkas took to Panama, they signed a Bilateral Arrangement on Migration and Protection seeking to improve migration management. Also in April, Biden and Mexico President Andrés Manuel López Obrador had a phone call to discuss migration and bilateral priorities.

These efforts build on initiatives and bilateral agreements reached in 2021 between U.S. officials and governments in the region and are complementary to the strategy to address the root causes of migration from Central America and to develop a collaborative migration management strategy, announced by the administration last July. Vice President Kamala Harris’ June 2021 visit to Guatemala culminated in initiatives addressing anti-corruption efforts and living conditions in the country, and her trip to Mexico resulted in bilateral agreements that addressed economic collaboration, human smuggling, and root causes of migration. In October 2021, the governments of the United States and Mexico also signed the Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities—a new security cooperation plan that replaces the Merida Initiative. As WOLA has previously noted, the Bicentennial Framework included actions against human smuggling but fell short on migrant protections. Apart from these steps, the administration has also removed some barriers to unifying children with their families, expanded pathways to protection such as the reopening of the Central American Minors program, and allocated additional temporary work visas, among other measures.

The United States has also provided aid to border security forces in the region. In 2019, under the Trump administration, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security signed agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, which served to “deploy officials from U.S. Customs and Border Protection and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to advise and mentor host nation police, border security, immigration, and customs counterparts.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents have also trained immigration authorities in countries in Latin America, including Mexico and Panama. These trainings are troublesome considering the record of human rights abuses exhibited by U.S. border agencies, as WOLA has documented. We have already seen the impact of these agreements. In January 2020, the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) carried out an unauthorized operation in Guatemala, where CBP personnel transported Honduran migrants in unmarked vans to the Guatemala-Honduras border, without any protocols in place to ensure the human rights of migrants or conduct asylum screenings.

On April 1, 2022 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a statement indicating that Title 42 would be lifted by May 23. Section 265 of Title 42, U.S. Code permits suspending “entries and imports from designated places to prevent spread of communicable diseases.” The Trump administration interpreted this section in 2020, at the outset of the pandemic, as allowing the U.S. government to systematically expel migrants and refugees without respecting their right to seek asylum—even though it violated international human rights law as the UNHCR has repeatedly observed. However, the CDC statement to lift Title 42 has seen political backlash from U.S. policymakers. Several GOP-led state governments filed lawsuits to block the termination of the policy, and some members of the Democratic Party expressed concern that the Biden administration was unprepared for a surge in the number of migrants and asylum seekers at the border. On May 20, the Trump-appointed Louisiana judge hearing the case extended the temporary order, pausing the Biden administration’s efforts to wind down the policy as the lawsuit continues. Legislation introduced in Congress would also extend Title 42 until the U.S. terminates the COVID-19 emergency declaration.

Even with Title 42 in place, CBP officials have been granting more exemptions, allowing some migrants a chance to seek protection in the country. While steps to re-open the U.S border to asylum seekers are welcome, comments by U.S. officials about expected decreases in migration after Title 42’s lifting due to the increased use of consequences, such as criminal prosecutions and jail time for illegal entry into the country, illustrate that enforcement continues to be at the center of U.S. policy.

The U.S. government has also maintained a deterrence strategy through its messaging. Most notably, in June 2021, Vice President Kamala Harris told migrants “do not come” while speaking at a conference in Guatemala. This message has been disseminated in different forms through official social media channels thereafter. For instance, the U.S. Embassy in Mexico earlier this year suggested in a tweet that the tragic death of a Venezuelan child while trying to cross into the United States showed the need for migrant families to “value” their children’s lives by not migrating without documentation. In April, the embassy retweeted the U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juárez’s message contending that undocumented migration causes danger and tragedies. More recently, CBP launched the campaign “Say No to the Coyote” to dissuade migrants from Honduras and Guatemala from taking the journey.

This rhetoric fails to address the very real dangers forcing thousands of people to leave their homes. It also does not recognize that the high risks of migration today are the result of a systemic, collective failure to protect the human rights of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers.

Beyond international efforts and commitments such as the Global Compacts on Refugees and for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, countries in the Western Hemisphere have responded to migration through regional agreements, bilateral initiatives, and annual conferences. Regional and sub-regional integration mechanisms that include several countries, such as the Andean Community of Nations (1969), the Southern Common Market or MERCOSUR (1991), and consultation mechanisms such as the South American Conference on Migration (2000), the Ibero-American Network of Migration Authorities (2012), and the Quito process (2018) have established guidelines and shared best practices for human mobility. The Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework (2017), involving the countries of Central America and Mexico, encourages regional collaboration with a focus on protection and solutions—featuring a participatory approach that consults the people in need of protection. The South American Conference on Migration or Lima Process provides a platform for participating countries to consult on various migration-related topics, including displacement driven by climate change. The Regional Conference on Migration or Puebla Process offers another space for collaboration and discussion among member countries.

Since taking office, the Biden administration has also co-convened high-level ministerial meetings on migration. In October 2021, Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with Ministries of Foreign Relations and high-ranking representatives from Latin American and Caribbean governments in Bogota, Colombia to discuss regional migration challenges and solutions. In April 2022, Secretary Blinken and Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas attended a Ministerial Conference with foreign and security ministers, multilateral development banks, and international organizations in Panama City, Panama to discuss cooperation on regional migration and anti-corruption efforts.

Despite growing efforts toward greater collaboration, the region still lacks the capacity to coordinate a rights-respecting response that effectively and humanely manages the flow of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Instead, governments have prioritized border security and migration enforcement efforts, forcing migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers to confront serious dangers while in transit, and the risk of being turned back at any given checkpoint.

WOLA has proposed concrete solutions. The guiding principles for a regional framework on migration and protection in the Americas, developed by WOLA and partners, focus on guaranteeing respect for the rights of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees “through increased protection pathways and complementary legal pathways as well as humanitarian assistance, and access to justice” which also address the needs of particular populations, including Black, Indigenous, women, children, disabled, and LGBTQ+ migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. As governments commit to a hemispheric declaration on migration and protection at the Summit in June they should ensure that there are concrete mechanisms to follow-through with the commitments made in consultation with all relevant stakeholders, including civil society organizations, and prioritize a protection-centered approach over enforcement and deterrence.