With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

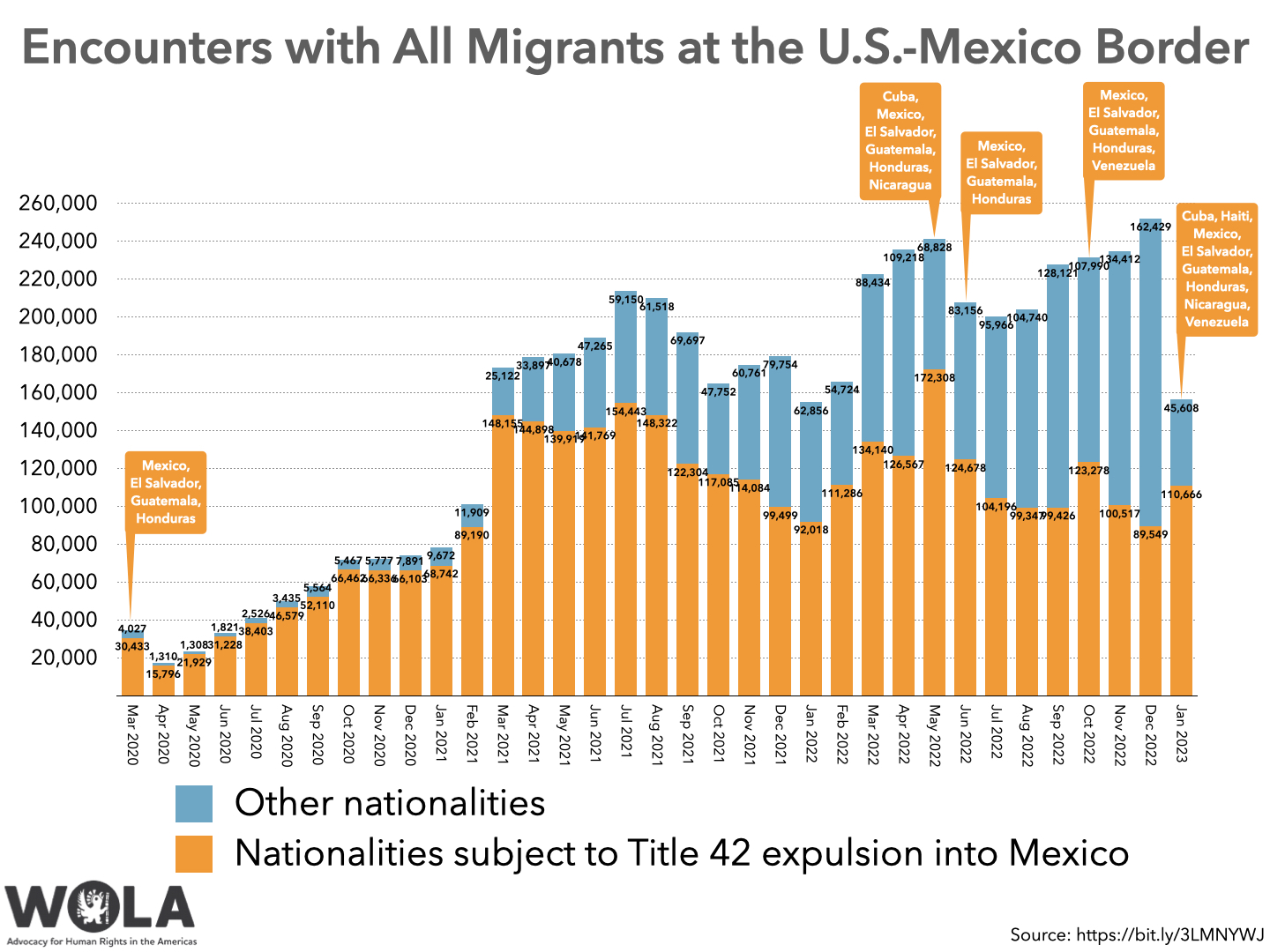

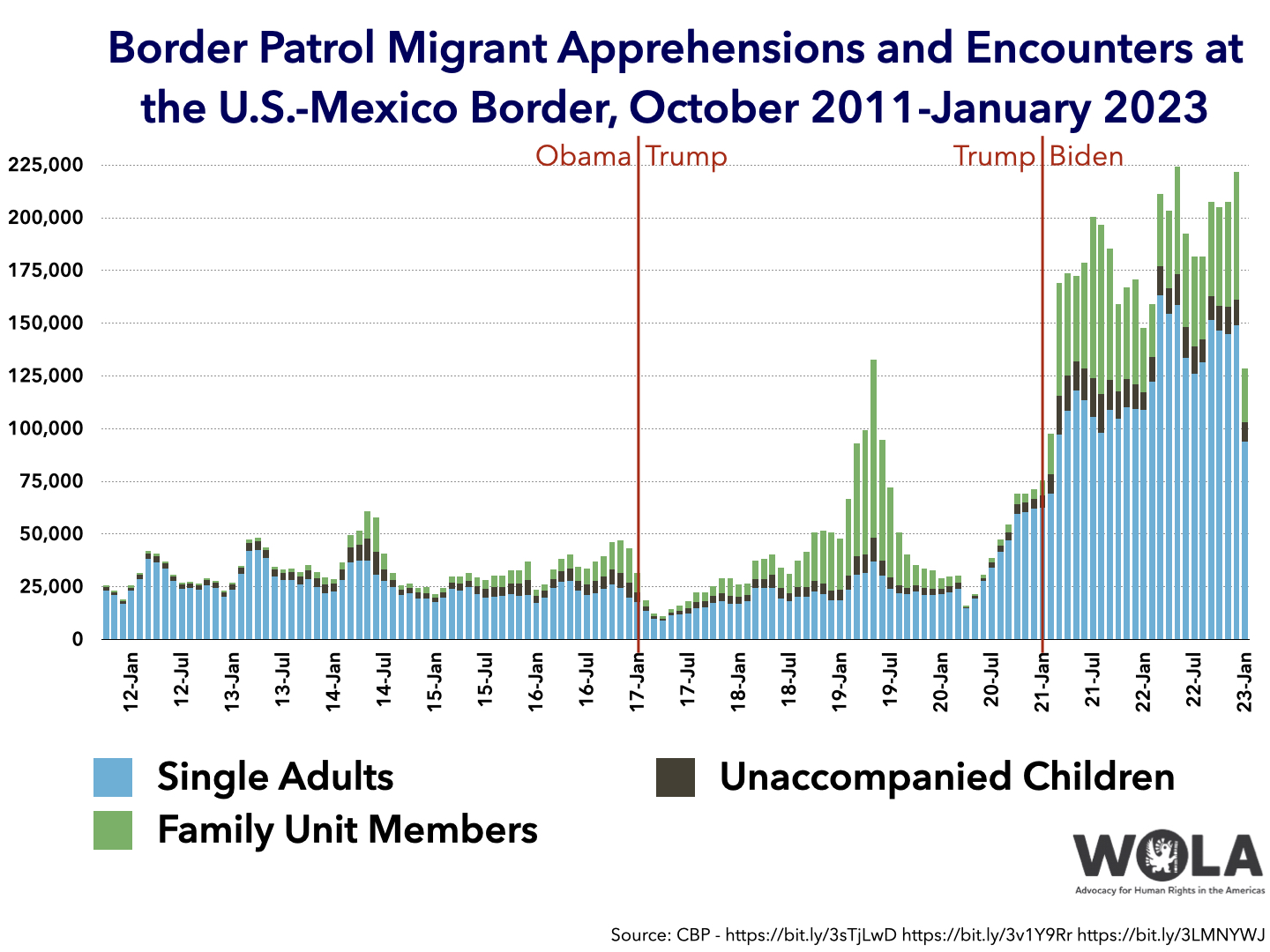

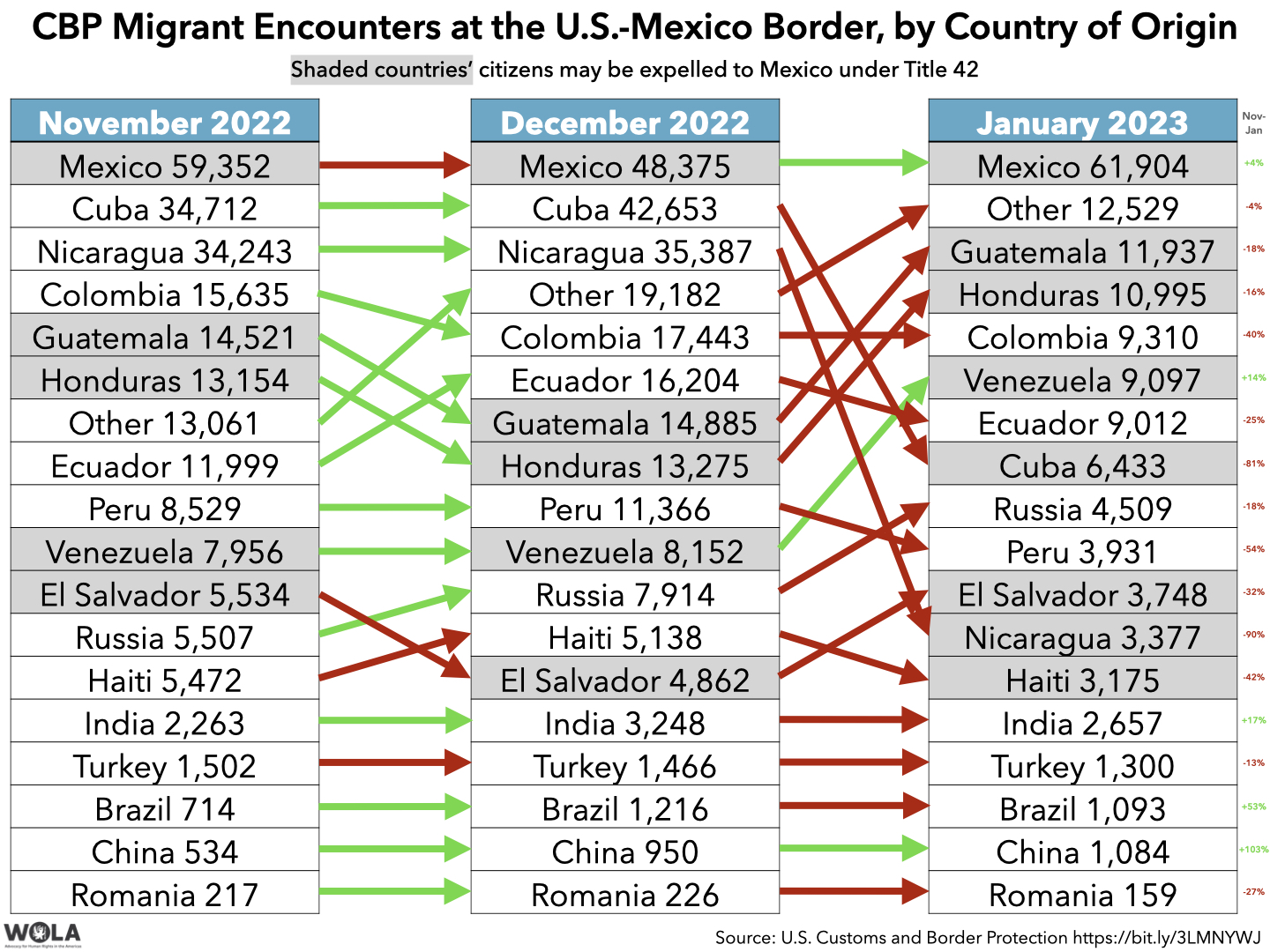

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) published data on February 10 revealing a sharp drop in the number of migrants whom the agency encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border in January. The 40 percent decline in migrant encounters, to 156,274 in January from 251,978 in December, owes to the Biden administration’s January 5 expansion, from five to eight, of the number of countries whose citizens can be expelled immediately to Mexico under the “Title 42” pandemic authority. (Several recent WOLA Border Updates detail this expansion.)

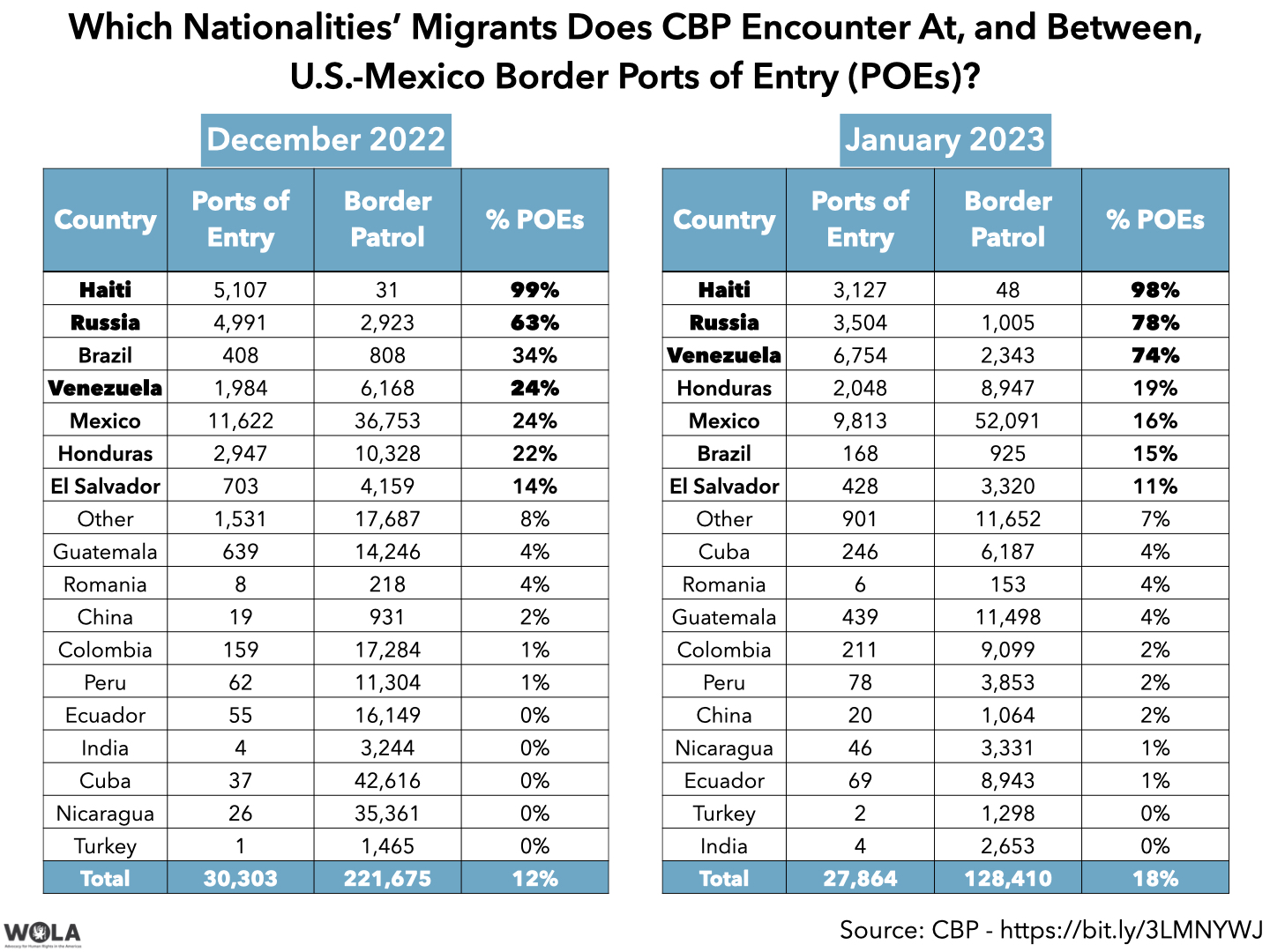

This was the smallest number of CBP U.S.-Mexico border migrant encounters since February 2021, the first full month of the Biden administration. The agency “encountered” 115,226 individual people 156,274 times in January. Of those “unique individuals,” 27,864 arrived at land-border ports of entry, which would leave a remainder of about 87,362 individuals taken into Border Patrol custody between the ports of entry.

41 percent of encounters ended with Title 42 expulsions, the largest percentage since June 2022. Nationalities most frequently expelled were:

Regardless of their susceptibility to expulsion, all nationalities’ migrant encounters declined from December to January except those from Mexico (+28%), China (+14%), and Venezuela (+12%); citizens of Mexico and Venezuela are subject to Title 42 expulsion, but for the first time, a majority of Venezuelan migrants were encountered at land-border ports of entry (official border crossings), instead of “in the field” between the ports, where Border Patrol operates.

This indicates that a significant number of Venezuelans were able to secure a limited number of Title 42 exemptions, many through use of a smartphone app (“CBP One”) that CBP began using in January to book appointments at ports of entry. CBP reported processing 21,661 Title 42 exemptions at ports of entry in January, including 9,902 who made appointments via CBP One between January 18 and 31.

“Over 20,000 individuals have scheduled an appointment via CBP One,” CBP’s release explained, “and the top nationalities who have done so are Venezuelan and Haitian.” The agency acknowledged that “the high demand for these appointments has meant that not all individuals seeking appointments have yet been able to schedule them,” a problem that has been widely reported (see WOLA’s February 2 Border Update).

Nationalities that declined most sharply were Nicaragua (-90%), Cuba (-85%), and Peru (-65%). Cuban, Nicaraguan, and Haitian citizens became subject to Title 42 expulsion into Mexico with the Biden administration’s January 5 policy change. 98 percent of Haitian migrants came to ports of entry in January, so expulsions were rare. It is not clear why migration from Peru and Colombia (-47%) declined, as those countries’ citizens are not subject to expulsion into Mexico.

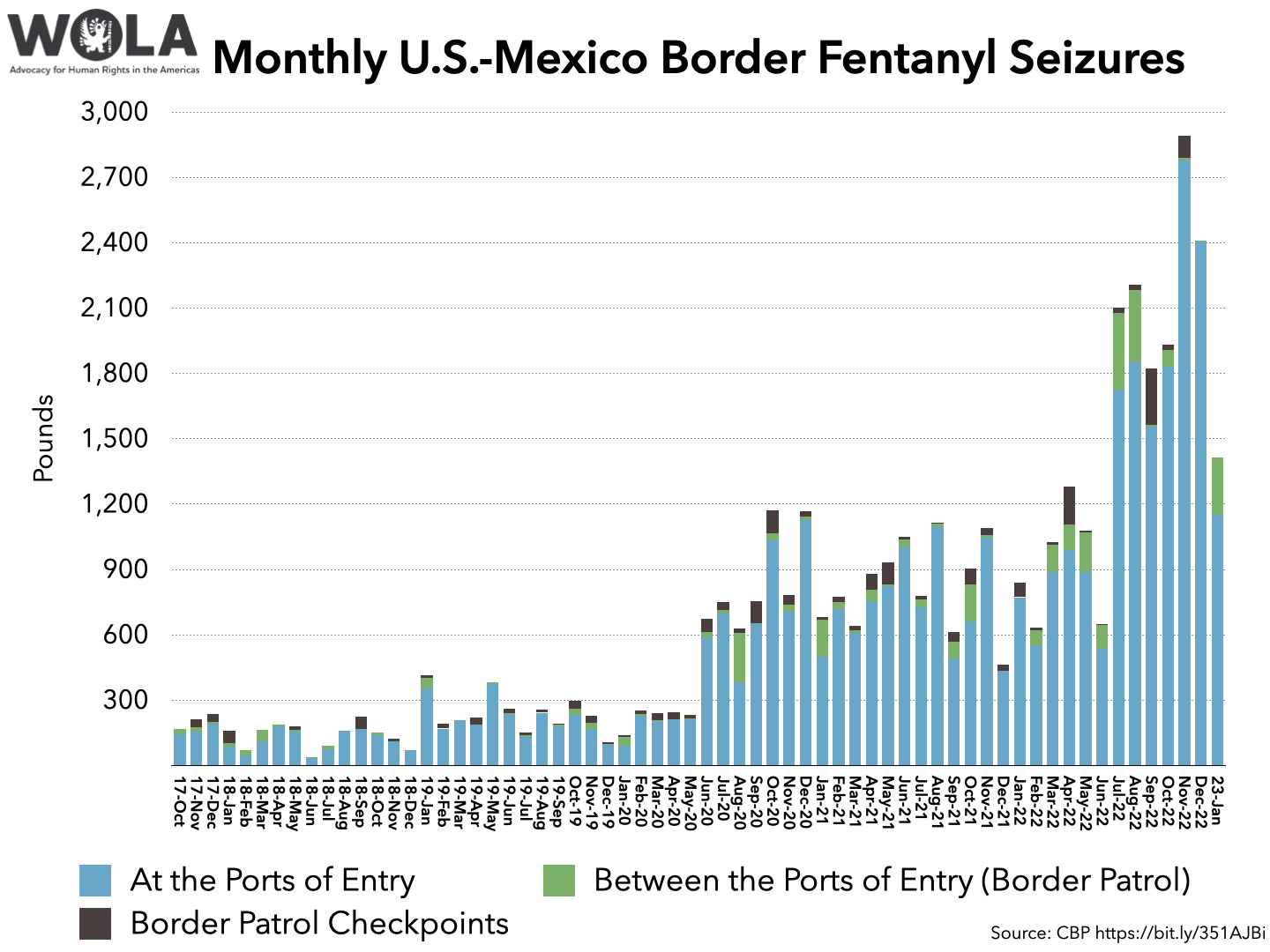

CBP’s data showed a slowdown in seizures of fentanyl in January: the 1,415 pounds seized were the fewest since June 2022. 81 percent of January fentanyl seizures took place at ports of entry. CBP’s 2023 fiscal year remains on pace to shatter annual fentanyl seizure records, with 8,645 pounds seized in 4 months. (The full-year record, set in fiscal 2022, is 14,105 pounds.) 94 percent of this year’s fentanyl seizures have taken place at the ports of entry, and another 1.5 percent at Border Patrol’s interior road checkpoints.

“What I can tell you from our cases, and the work that we do across the United States and across the world, is that virtually all the fentanyl that we are seizing in the United States is coming from Mexico. And we do believe that much of that is coming through ports of entry in California and Arizona,” Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Administrator Anne Milgram told a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on February 15.

Border Patrol reported 128,410 January “encounters” with migrants in January. On February 15, Chief Raúl Ortiz tweeted “Over 64,000 encounters in the past 14 days,” which would indicate that February’s encounters continue at a similar pace.

Some data points hint at a seasonal rise in migration so far in February. El Paso’s municipal “dashboard” of migration data in Border Patrol’s El Paso Sector shows a 7-day daily average of 1,041 migrant encounters there during the past week, up from 927 the prior week and 879 the week before (this is still down sharply from December’s daily average of 1,798). In Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Border Report cites management of the Casa del Migrante Nazareth seeing “between 25 to 30 people per day” seeking shelter “when a year ago it was half of that.” Many of the new arrivals are asylum seekers who have CBP One appointments at the Laredo port of entry.

A bus carrying migrants who had recently passed through the treacherous Darién Gap jungle region, between Colombia and Panama, plunged off a precipice in Panama’s Chiriquí province, not far from the border with Costa Rica, in the early morning hours of February 15. At least 39 of the migrants aboard, including families and children, have reportedly died.

After migrants emerge from the Darién Gap’s 60-plus life-threatening miles, Panamanian authorities attend to them at rustic rural shelters (Migration Reception Stations, Estaciones de Recepción de Migrantes, or ERMs), then whisk them out of the country on privately contracted buses like the one involved in this week’s tragedy. Migrants are charged US$40 apiece for transportation to the Costa Rica border.

“Most of them, however, lack the resources to meet these expenses, so they must remain in the ERMs, sometimes for long periods of time,” reads a December 9 letter to Panamanian authorities, made public this week, from several independent experts and special rapporteurs from the UN human rights system.

The letter recounts several serious findings of abuse of migrants’ rights during their passage through the Darién and Panama.

The UN-affiliated experts’ letter also questions Panamanian authorities’ absence from the Darién Gap jungle route, which leaves migrants at the mercy of violent criminal groups and places them in life-threatening situations. “The records, forensic databases and protocols for the identification of deceased persons, as well as for the search for missing persons in the Darién jungle, are unknown.”

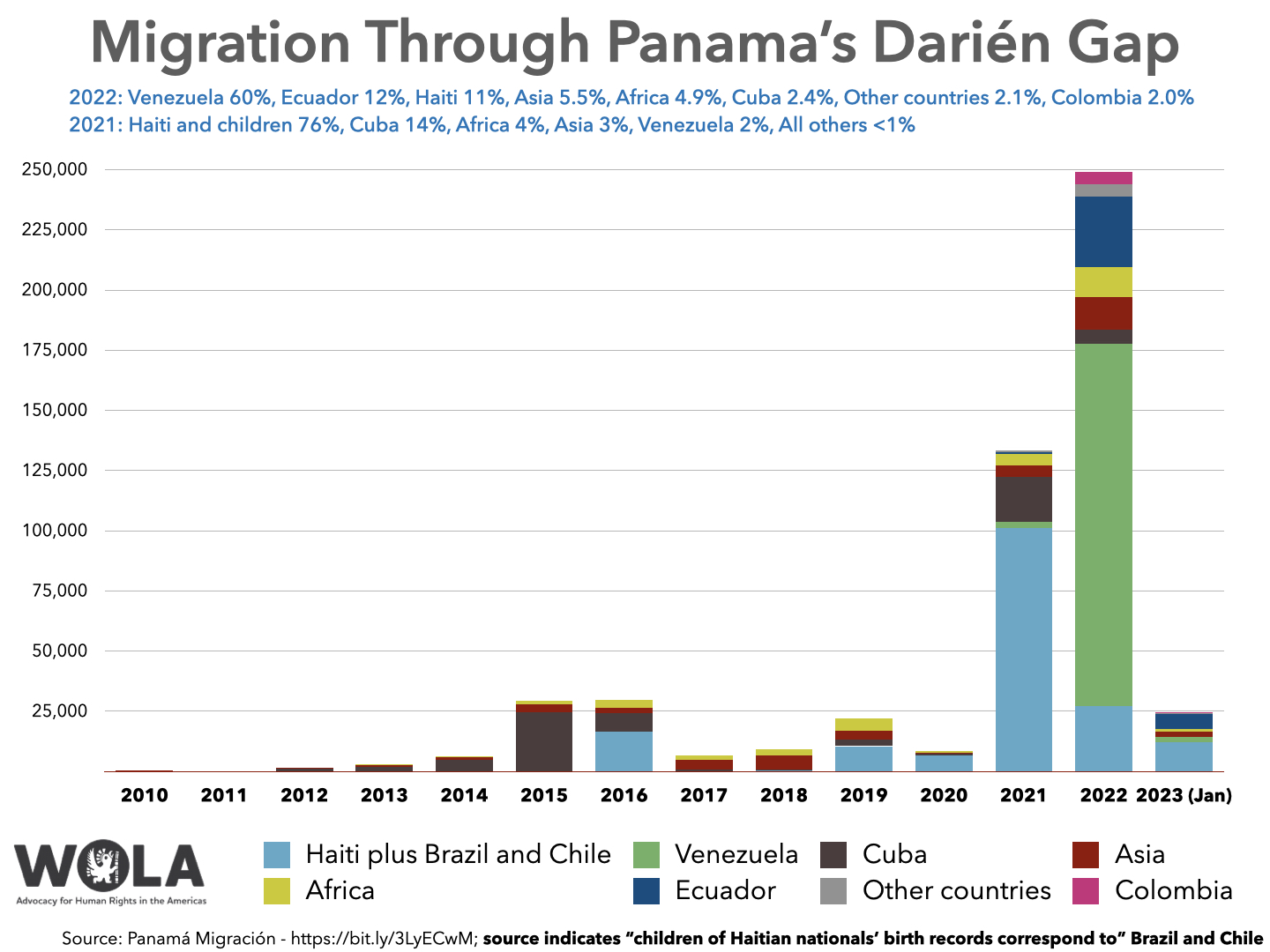

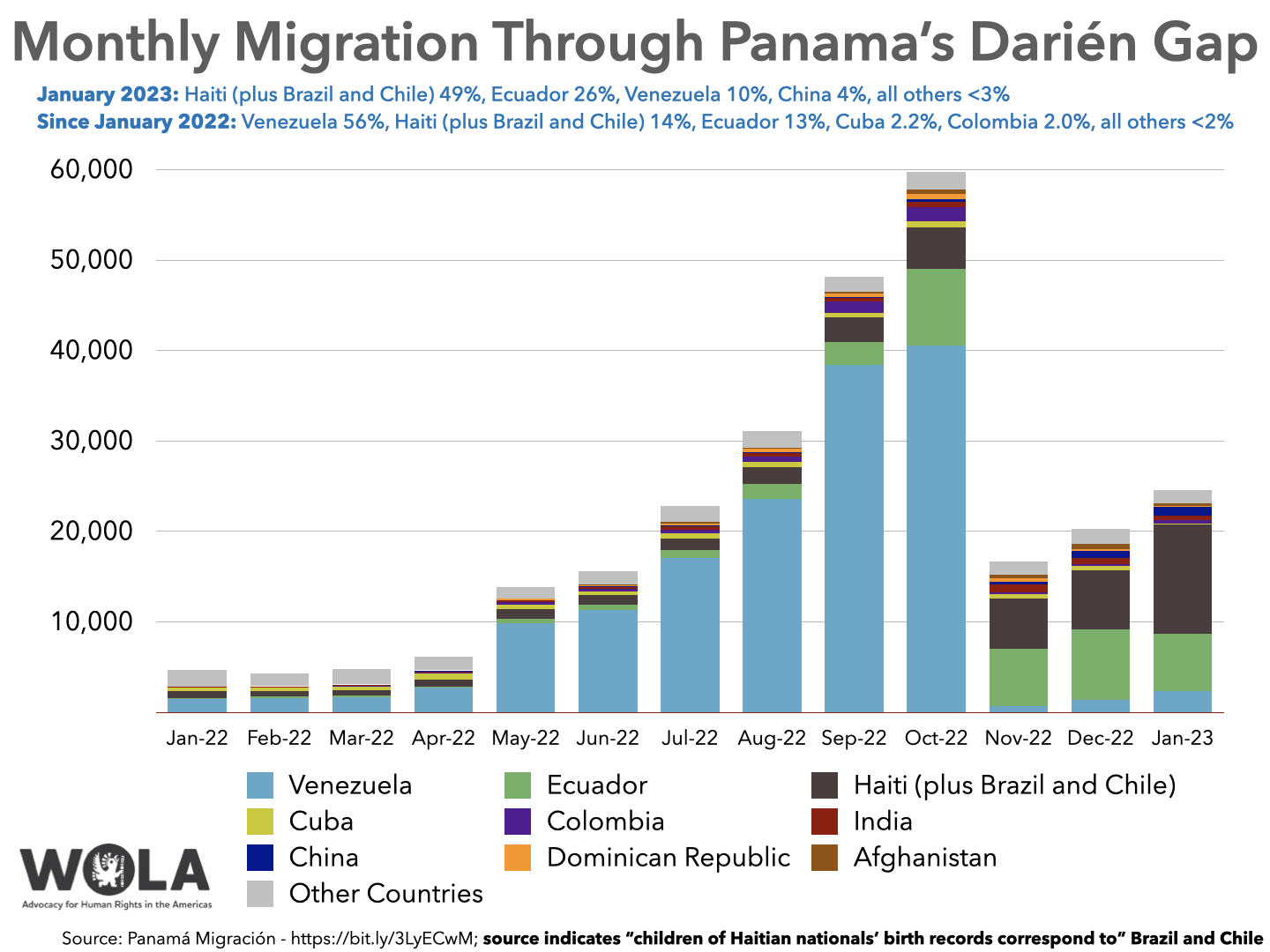

A previously unimaginable total of 248,284 people migrated through the Darién Gap in 2022; 150,327 were citizens of Venezuela. Migration fell sharply after October 12, when the Biden administration announced an agreement with Mexico to use Title 42 to expel Venezuelan migrants into Mexican territory. Numbers have begun to increase again, however, from 16,632 migrants in November 2022, to 20,297 in December, to 24,634 in January.

The principal nationalities of migrants traversing the Darién Gap in January were:

Of these “top ten” nationalities, only five are from Latin America and the Caribbean.

The foreign minister and defense minister of Colombia, along with the U.S. ambassadors to Colombia (acting) and Panama, paid February 14 visits to the Colombian and Panamanian extremities of the Darién Gap region, accompanied by senior Panamanian officials. Colombia and Panama “agreed to increase joint military operations in the Darien jungle region to tackle drug trafficking, illegal mining, and irregular migration,” Reuters reported.

A statement from Colombia’s Defense Ministry cites agreement to build, with U.S. support, a “binational observation post” in the village of Cabo Tiburón and a military base in the village of Sapzurro, both in the municipality of Acandí, Chocó, Colombia. The U.S. government is also studying with the two governments “the possibility of installing a maritime radar in this area.”

When it expanded Title 42’s scope in October and January to include expulsions to Mexico of Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, the Biden administration created another pathway. Up to 30,000 monthly would-be migrants from those countries may now apply remotely for a two-year “humanitarian parole” status in the United States—provided they have passports and someone in the United States willing to sponsor them.

“During January,” CBP reported, “11,637 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans were paroled into the country” under this new process. This is far fewer than the monthly allotment of 30,000, but the process is new.

Reports point to surging demand at those countries’ passport authorities. In Haiti, the Associated Press reported, the intense demand for passports has delayed U.S. parents’ ability to get their legally adopted children out of Haitian orphanages. “The ensuing demand for Haitian passports has overwhelmed Haiti’s passport office in the capital, Port-au-Prince, where people with appointments cannot squeeze through the aggressive crowd or secure new appointments.”

In Cuba and elsewhere, another AP report documents people—in some cases, probably fraudulently—offering on Facebook and elsewhere to serve as applicants’ sponsors, for fees of up to $10,000. Immigration attorneys interviewed by AP “said they could find no specific law prohibiting people from charging money to sponsor beneficiaries.”

Republican-governed states continue to press a lawsuit seeking to block the humanitarian parole program (discussed in WOLA’s January 27 Border Update). They filed a preliminary injunction on February 14 seeking to halt the program while deliberations continue. Legal expert Aaron Reichlin-Melnick of the American Immigration Council said on Twitter that no action is expected for “at least a month or two.”

In what the Texas Observer’s Jason Buch calls a “power grab,” a senior Border Patrol official gave testimony in Texas’s state legislature asking for adjustments to the state penal code that would allow this federal agency’s personnel to enforce Texas state law.

In a November 2022 hearing in Austin, Carl Landrum, chief of Border Patrol’s Laredo sector, asked legislators to make a “slight adjustment” to the Texas Penal Code that would allow Border Patrol agents “to arrest and assist in the prosecution of all state felonies and, he said, ‘some misdemeanors.’”

Under the administration of recently re-elected Governor Greg Abbott (R), a fierce critic of President Joe Biden’s border and migration policies, Texas police have arrested and jailed several thousand migrants on charges of trespassing, a misdemeanor. If the Republican-majority legislature adopts Landrum’s proposal, Border Patrol could play a more formal role in Gov. Abbott’s border crackdown, “Operation Lone Star,” which the Biden administration has criticized.

The Texas Observer notes that some Border Patrol agents are already, in practice, supporting Operation Lone Star.

The ACLU of Texas found that at least 25 percent of about 350 trespassing arrests made during August involved Border Patrol agents. In some cases, agents directed troopers to immigrants on private property. In others, the agents detained and held people until state police officials could arrive and arrest them.

“What makes Landrum’s request so unusual is that it came from a border patrol sector chief in the context of a highly politicized state policy,” the Texas Observer noted. Citing Victor Manjarrez, a former Border Patrol agent who heads the University of Texas at El Paso’s Center for Law and Human Behavior, it added, “Usually, when someone as senior as Landrum testifies to legislators, what they say is first approved by Washington officials.”

The Texas legislature is considering a new request for $4.6 billion from Texas taxpayers to support Operation Lone Star for the 2-year period that runs from September 2023 to August 2025. $2.25 billion would support a continued deployment of Texas National Guard personnel along the border, at Gov. Abbott’s command. Much of the rest would go to Texas’s Department of Public Safety, which includes state police.

Texas’s state Military Department told legislators that its current deployment of 4,576 National Guard troops—down from as many as 10,000 a year ago—is costing the state “between $92 million and $101 million per month.” The Department is using some emergency fund transfers to come up with the $459.3 million it needs to support the military deployment through August.