With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

In a February 6 brief filed before the Supreme Court, the Biden administration reiterated its intent to terminate the U.S. government’s COVID-19 “public health emergency” on May 11, 2023. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) August 2021 order prolonging the Title 42 pandemic policy, which mandated that migrants be expelled from the U.S.-Mexico border regardless of asylum needs, states that Title 42 ends when the public health emergency ends.

This will be the third declared end date of the Title 42 policy, which the Trump administration instituted in March 2020 and both administrations have since used to expel migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border 2.5 million times. Mexico has agreed to accept expulsions of its own citizens and, in a list that has expanded since October 2022, those of seven other countries (Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Venezuela).

The CDC declared in April 2022 that the COVID pandemic was no longer so severe as to justify Title 42, and had set an end date of May 23, 2022. Several Republican-governed states filed suit in a Louisiana federal court to block the policy’s termination, and the Supreme Court kept the policy in place while arguments proceeded. In a separate case, a Washington, DC federal judge struck down the Title 42 policy in November 2022, calling it “arbitrary and capricious” and setting a termination date of December 21, 2022. That decision, too, came under challenge from Republican states, which convinced the Supreme Court to order that Title 42 remain in place while the justices considered their appeal.

The Biden administration’s latest filing argues that the Republican states’ challenge is moot, because ending the government’s COVID-19 state of emergency undermines any basis for keeping Title 42 in place. (“Title 42” refers to the part of the U.S. Code dealing with “Public Health and Welfare.” It is hard to justify expelling migrants under a public health provision after the public health emergency ends.)

The CDC’s order had spelled out two ways of ending the Title 42 policy: either CDC determining it was no longer necessary, or the larger public health emergency coming to an end. The Republican states’ challenge blocked the first path. The administration’s new brief spells out the second path.

While Title 42 is likely to end on May 11, nothing is guaranteed. Republican state governments have had success challenging this and other Biden administration policies in the federal judiciary’s Fifth Circuit, known for its judges’ conservative tendency. While these states have no interest in maintaining the COVID emergency—they have long chafed under pandemic restrictions—they may seek to convince a Fifth Circuit judge to concoct a means to exclude protection-seeking migrants, at a time of very high numbers of migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border.

In the U.S. Senate, meanwhile, a bipartisan group of senators led by Sen. Jon Tester (D-Montana) reintroduced legislation that would keep Title 42 in place for two months after the end of the COVID state of emergency, while requiring the administration to submit “a plan to address the impacts of the post-Title 42 migrant influx.”

The administration’s plan is taking shape. Its Supreme Court brief makes clear that it does not intend to restore fully the right to seek asylum at the border after May 11. It expects to put in place two related measures:

1) “In the coming weeks,” the brief reads, the administration will issue a proposed rule (first announced on January 5) that would reject many asylum seekers who passed through third countries en route to the U.S.-Mexico border and did not request asylum in those countries. Such migrants “will be subject to a rebuttable presumption of asylum ineligibility in the United States unless they meet exceptions that will be specified.”

Migrants’ rights advocates call this “transit ban” or “asylum ban” a “death sentence” because it is likely to return to danger people with legitimate protection claims. Under this ban, the only nationality not subject to this ineligibility would be Mexicans, who pass through no other country on their way to the border.

The Trump administration put in place a similar ban in 2019, only to see it struck down in federal court. The Biden administration is seeking to avoid that outcome with still-undetermined modifications and exceptions, and by submitting the policy to the federal government’s deliberative “notice and comment” rulemaking process.

“The Biden administration will undoubtedly argue that because the proposed rule imposes only a rebuttable presumption instead of an outright prohibition, it is distinguishable from Trump’s legal ban and will pass legal muster,” wrote the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies’ Karen Musalo at Just Security. “But the facts on the ground do not support even a presumption of safety and access to a full and fair procedure.”

In a February 8 letter to President Biden, Sens. Dick Durbin (D-Illinois, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee) and Alex Padilla (D-California, chairman of the Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Safety) objected to the “transit ban.” They recalled that current U.S. law allows asylum seekers to be sent to another nation under only two narrow circumstances: if the United States has a “safe third country” agreement with that nation (one only exists with Canada), or if the migrant was already “firmly settled” there. Very few asylum seekers’ cases meet either of these conditions. “We are deeply concerned,” the senators wrote, “ that establishing a higher standard for asylum based on passage through a third country would circumvent this statutory scheme and undermine the fundamental right to asylum, violating the letter and spirit of the law.”

2) Even if allowed to seek asylum, the administration plans to subject many migrants to expedited removal, requiring them to defend their cases within days of being apprehended, while still in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) or Border Patrol custody at the agencies’ jail-like holding facilities, and with little or no access to counsel. Those who fail “credible fear interviews” with U.S. asylum officers, usually held by videoconference or over the phone, will be swiftly removed from the United States.

As WOLA’s February 3 Border Update discussed, this proposal resembles two controversial Trump-era programs, known as PACR and HARP, that the Biden White House terminated shortly after Inauguration Day 2021. Migrant rights’ advocates contend that this swift process will end up sending to danger many asylum seekers with legitimate claims who are unable to frame their cases under such harsh circumstances.

Both the “transit ban” and expedited removal would involve swift deportation of large numbers of migrants, many of them from faraway countries. Flying them back to their countries of origin would be so costly that most would instead be released into the United States with dates to appear in U.S. immigration court—unless Mexico agrees to accept deportees access the land border, as it has done with those expelled under Title 42.

Mexico indeed may be close to agreeing to accept third-country deportees in a post-Title 42 context, the Washington Post reported on February 8, citing “four current and former U.S. officials familiar with the discussions.” It is quite possible, then, that U.S. authorities may continue to send large numbers of protection-seeking migrants back into Mexican border cities where services are scarce and security conditions are dangerous, as occurred with Title 42 and with the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy.

Mexico has not yet declared its intentions, though a February 6 statement from Mexico’s Foreign Relations Secretariat rejected any possible restart of the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the Biden administration to terminate in May 2022.

Mexican law in fact prohibits sending non-Mexican deportees into its territory. “Mexican authorities skirted that law with Title 42 expulsions by arguing that expelled migrants have not officially left Mexican territory,” the Washington Post explained, but deportations, which require processing in the U.S. immigration system, appear more clearly to violate Mexican law.

In October 2022 and January 2023, the Biden administration convinced Mexico to go along with expanded cross-border Title 42 expulsions of Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans by offering some of these countries’ citizens another pathway to protection in the United States. A “humanitarian parole” program now permits a cumulative total of up to 30,000 of those four countries’ citizens to enter the United States each month, and to remain in the country for up to two years, after applying online from outside the United States.

The humanitarian parole program is only open to migrants who have passports and someone in the United States willing to sponsor them. Both conditions favor migrants with more resources and connections, while migrants who do not meet them are expelled into Mexico if caught seeking to cross the border. The long-term result of this pair of policies could be a two-tiered system in which wealthier, more connected migrants end up in the United States, while poorer migrants end up in Mexico.

Some asylum seekers might be able to access a limited number of appointments to present themselves at border ports of entry using the CBP One app (discussed in WOLA’s January 20 and February 2 Border Updates). Mexican asylum seekers fleeing worsening violence in their country would meanwhile face greater challenges to protection under the expedited removal process.

Very little certainty currently exists about what might happen on May 11, 2023. If the Biden administration gets its way, however—convincing federal courts and the Mexican government to go along—we now have a sense of what would happen. Title 42 would be replaced by a new regime that rejects most asylum seekers and sends potentially thousands per month back into Mexico.

The House of Representatives’ new Republican majority held the second of a planned series of hearings about border security and migration. Republicans are aiming to probe an issue they perceive to be a political liability for the Democratic Biden administration at a time of record migrant arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Following a February 1 Judiciary Committee hearing with non-governmental witnesses, the House Oversight and Accountability Committee met for five hours on February 7 to hear testimony from two Border Patrol sector chiefs. (Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border into nine geographic sectors.) Rio Grande Valley, Texas Sector Chief Gloria Chavez and Tucson, Arizona Sector Chief John Modlin took a variety of questions from Republican and Democratic members’ very different perspectives.

Committee Chairman Rep. James Comer (R-Kentucky) set the stage with opening remarks blaming the Biden administration for “the worst border crisis in American history.” Comer had initially invited four sector chiefs to testify. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had countered with an offer to have Border Patrol Chief Raúl Ortiz testify instead. The two sector chiefs’ presence represented a compromise.

Comer is among House Republicans who have declared an intention to impeach DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas (an effort that would almost certainly fail in the Democratic-majority Senate), accusing him of failing to secure the U.S.-Mexico border. The New York Times noted, though, that Republican Committee members at the February 7 hearing “barely brought up Mr. Mayorkas, and instead focused on blaming Mr. Biden for the situation at the border.” A likely reason may have been avoiding the awkwardness of appearing to make the uniformed Border Patrol chiefs respond to attacks on Mayorkas.

Among many points discussed at the hearing:

A frequent point of contention between committee members was cross-border smuggling of fentanyl, a potent opioid mainly produced in Mexico, currently the cause of record numbers of overdose deaths in the United States.

Republican committee members repeatedly blamed the Biden administration for the ready availability in the United States of fentanyl smuggled across the border from Mexico. They did not call any witnesses, however, from the border law enforcement agency that sees by far the most fentanyl seizures.

CBP’s Office of Field Operations (OFO), which mans the land border’s official ports of entry, was not represented at the hearing, even though its personnel seized 85 percent of border-zone fentanyl during the past two fiscal years.

DHS and DEA reporting has noted for years that fentanyl, a drug so potent that massive numbers of doses fit in small packages, is most often smuggled in cars, cargo vehicles, and on the bodies of individuals passing through official border crossings.

In a February 2 briefing with reporters, DHS Secretary Mayorkas said it was “unequivocally false that fentanyl is being brought to the United States by non-citizens encountered in between the ports of entry who are making claims of credible fear and seeking asylum.” According to CBS News, he added, “The vast, vast majority is sought to be smuggled through the ports of entry and tractor-trailer trucks and passenger vehicles.” CBS added, “Data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission shows that between 2017–2021, 86% of fentanyl trafficking offenders were American citizens.”

The two Border Patrol sector chiefs represent the agency responsible for areas of the border between the ports of entry, which seized the other 15 percent: 5 percent at interior checkpoints, and 10 percent “in the field” (often at road stops). That share shrank to 3 percent during the first quarter of fiscal year 2023, which is on pace to break seizure records for the fifth consecutive year.

Nonetheless, a review of the hearing transcript shows no instance in which either Border Patrol chief clearly affirmed that the majority of fentanyl is passing through ports of entry. Republican legislators meanwhile speculated that undetected amounts must be carried by the migrants whom they called “gotaways,” though the sample of seizures from apprehended migrants does not reflect such a trend.

“If we want to stop fentanyl overdoses, we should push for addiction treatment programs and treat this crisis as a public health issue—not baselessly blame immigrants for political theater,” Rep. Greg Casar (D-Texas), whose district includes San Antonio, said at the hearing.

CBP has been deploying non-intrusive scanners, canine teams, and other methods to detect fentanyl at the border. The rollout of technologies has been slow, however. “CBP officials have acquired approximately 135 non-intrusive inspection systems, though just 10 have been deployed to operational locations in Texas, Arizona and California,” CBS reported. “By providing 123 new large-scale scanners at Land Points of Entry along the Southwest Border by Fiscal Year 2026,” a February 7 White House fact sheet reads, CBP “will increase its inspection capacity from what has historically been around two percent of passenger vehicles and about 17 percent of cargo vehicles to 40 percent of passenger vehicles and 70 percent of cargo vehicles.”

During the weeks of February 13 and 20, the House of Representatives will be out of session for its President’s Day recess. At least two committees, however, plan to hold “field hearings” at the border. The Energy and Commerce Committee will meet in Weslaco, Texas (in the Rio Grande Valley) on February 15. The Judiciary Committee may convene in Yuma, Arizona during the week of the 20th.

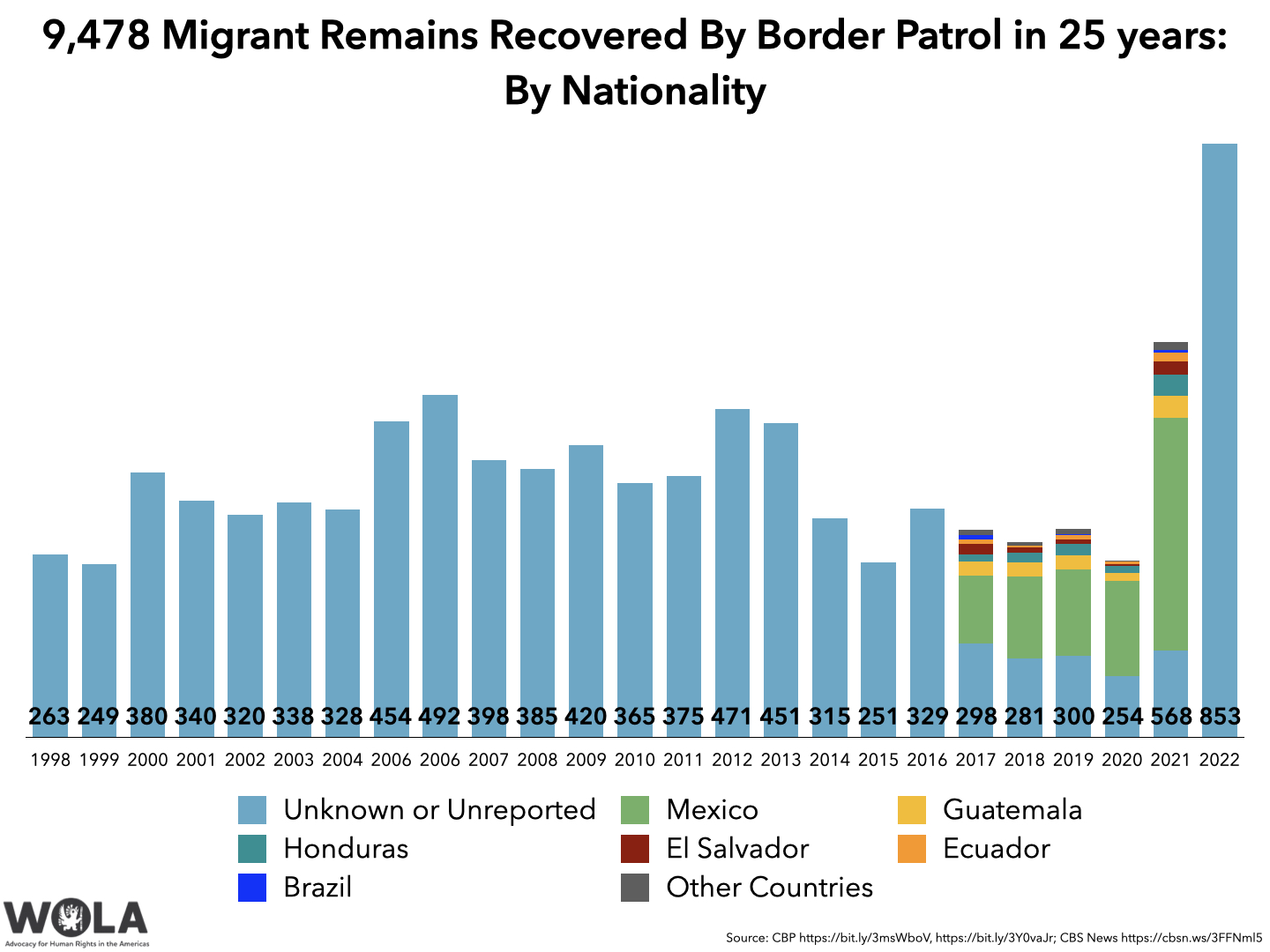

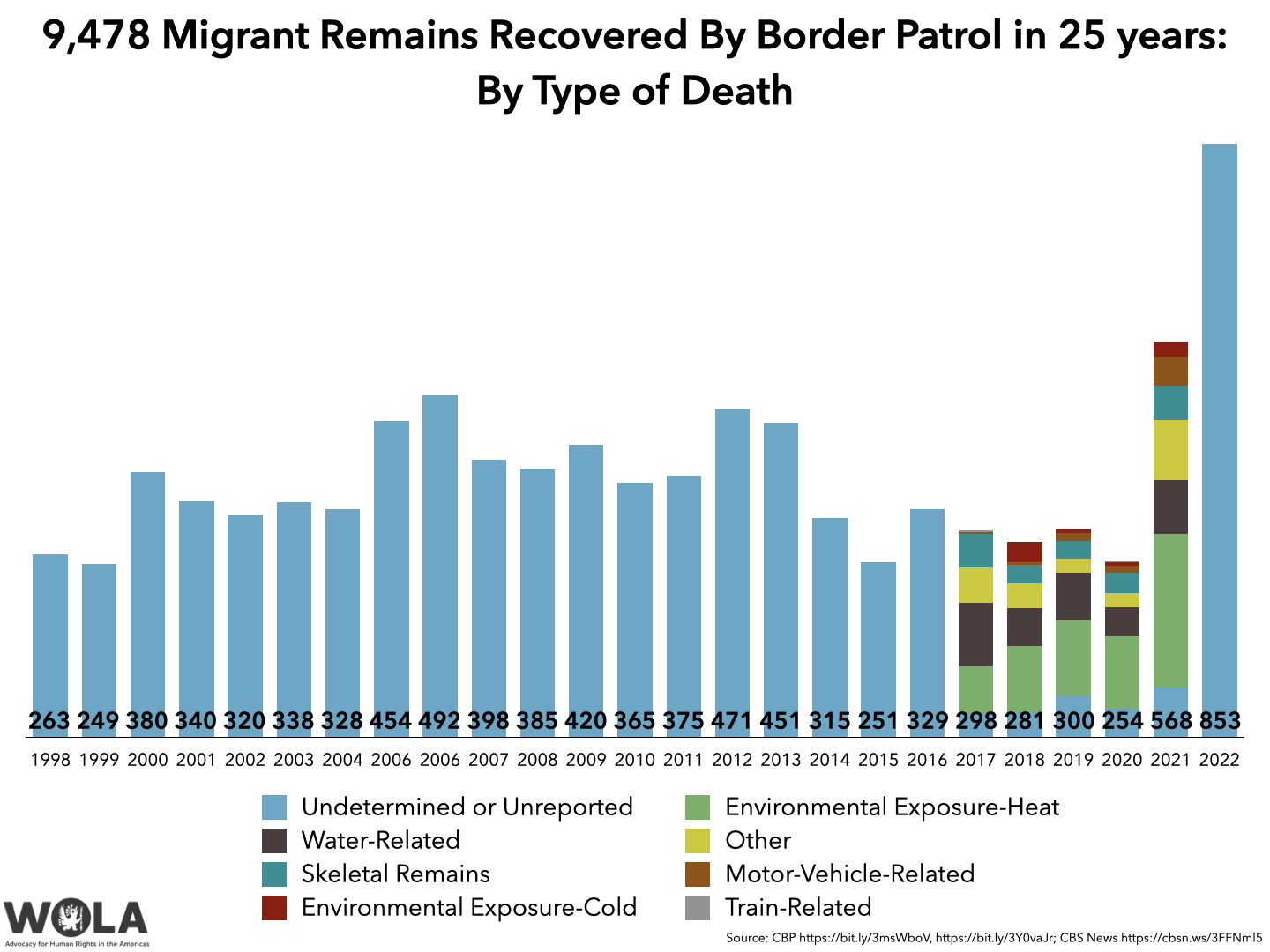

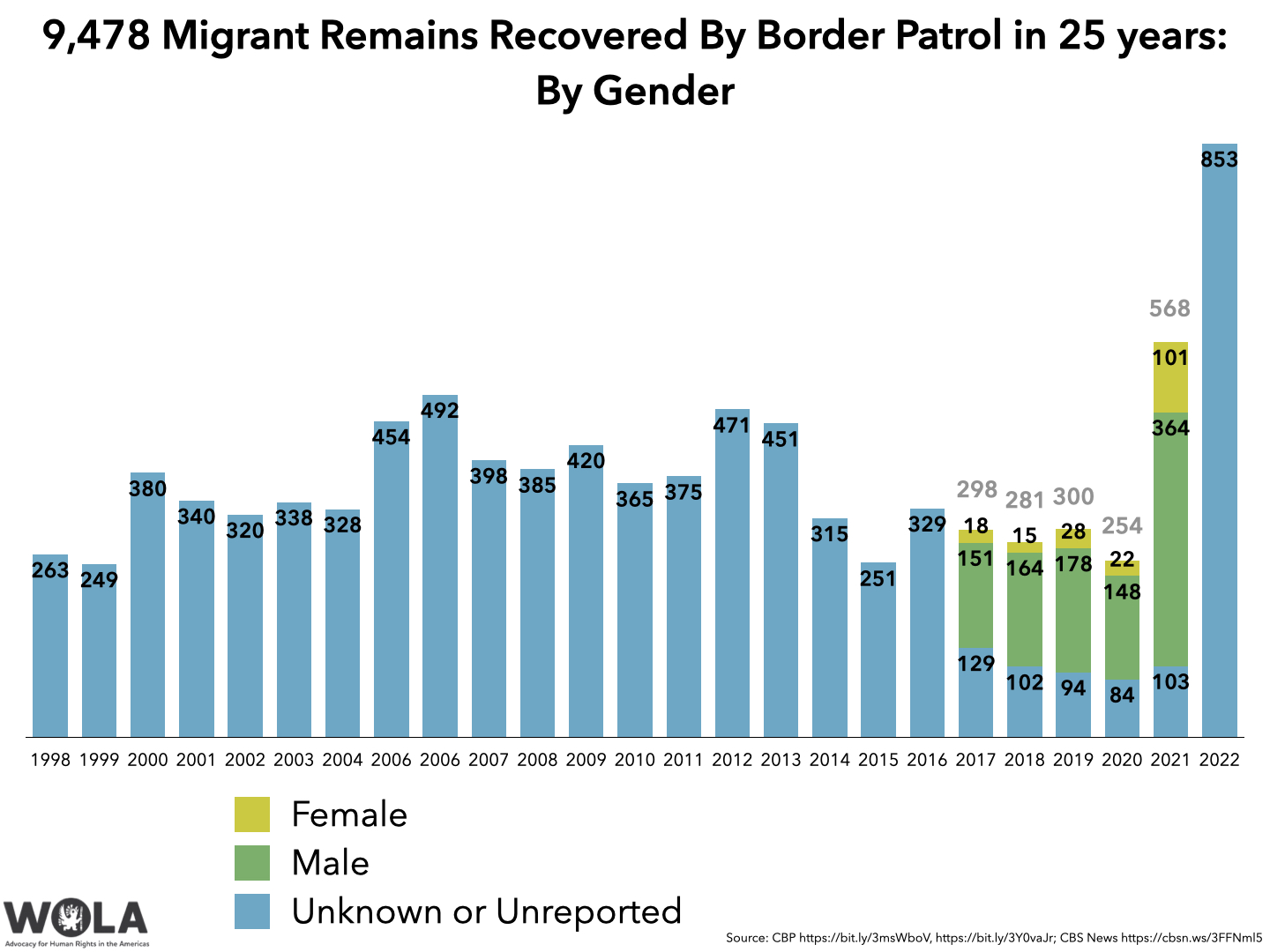

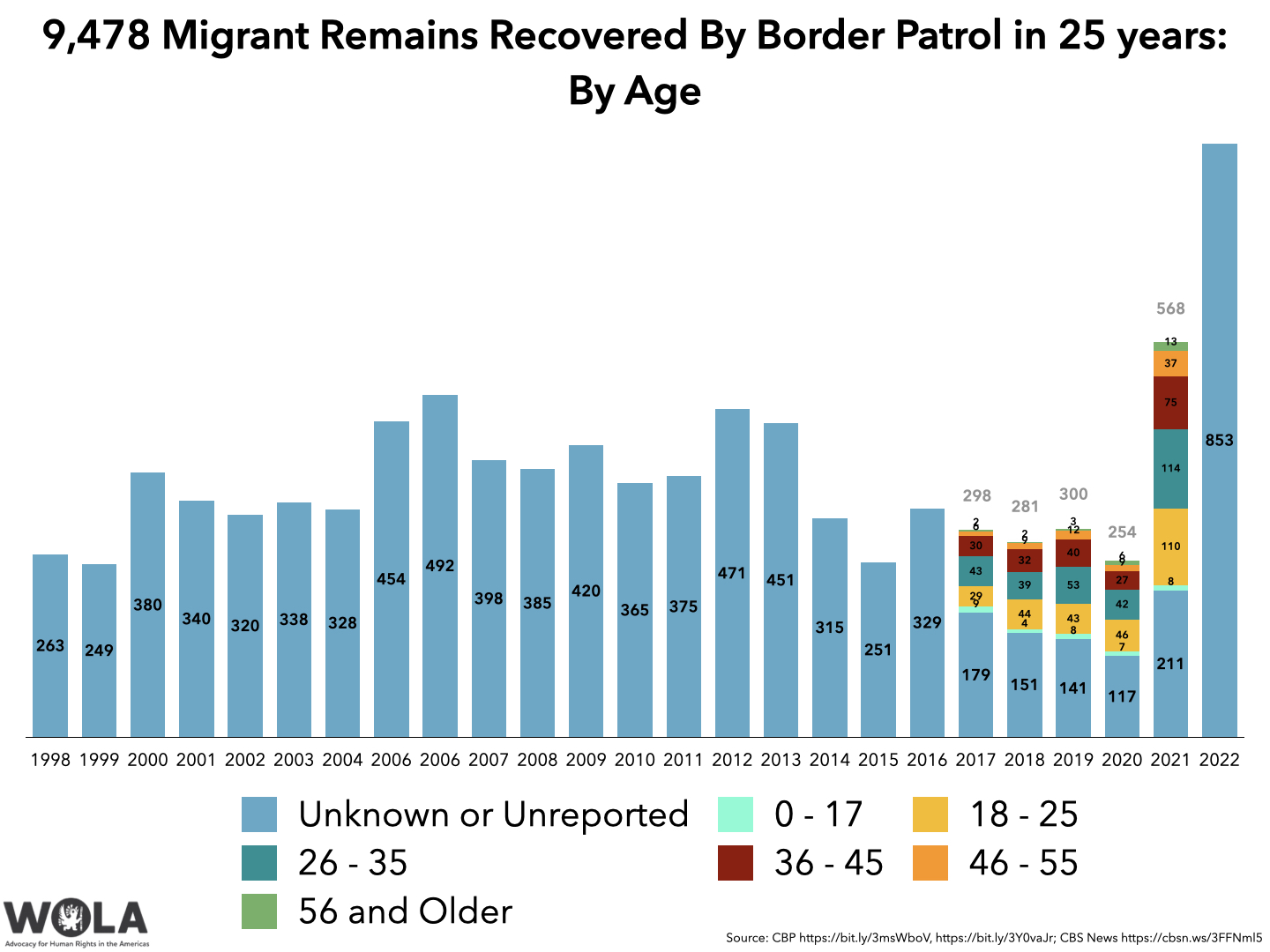

A February 6, 2023 CBP report offers an unprecedented level of detail about the remains of migrants that the agency, mainly its Border Patrol component, has found on U.S. soil in the U.S.-Mexico border region. The report documents the remains of 568 migrants found in 2021, which at the time was a record. (CBS News, citing a CBP source, reported in October that the 2022 total reached 853 migrant deaths.)

The “Border Rescues and Mortality Data” report is the first edition of an annual report required by Congress, most specifically in Section 5(a) of the Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains Act of 2019 ( P.L. 116-277). That law required CBP to produce a detailed report on migrant deaths in fiscal 2021, which ends on September 30, 2021, by the end of December 2021. The agency issued it more than a year late, and its report for fiscal 2022 is still pending.

The report nonetheless provides much new information, gathered by CBP’s Missing Migrant Program, which has been in existence since 2017.

We now know the following about the five year period 2017-2021.

Of the 1,121 migrants whose nationality could be determined, 72 percent were citizens of Mexico; 9 percent were citizens of Guatemala; 7 percent were from Honduras; 5 percent were from El Salvador; 3 percent were from Ecuador; 1 percent were from Brazil; and 3 percent were from 11 other listed countries.

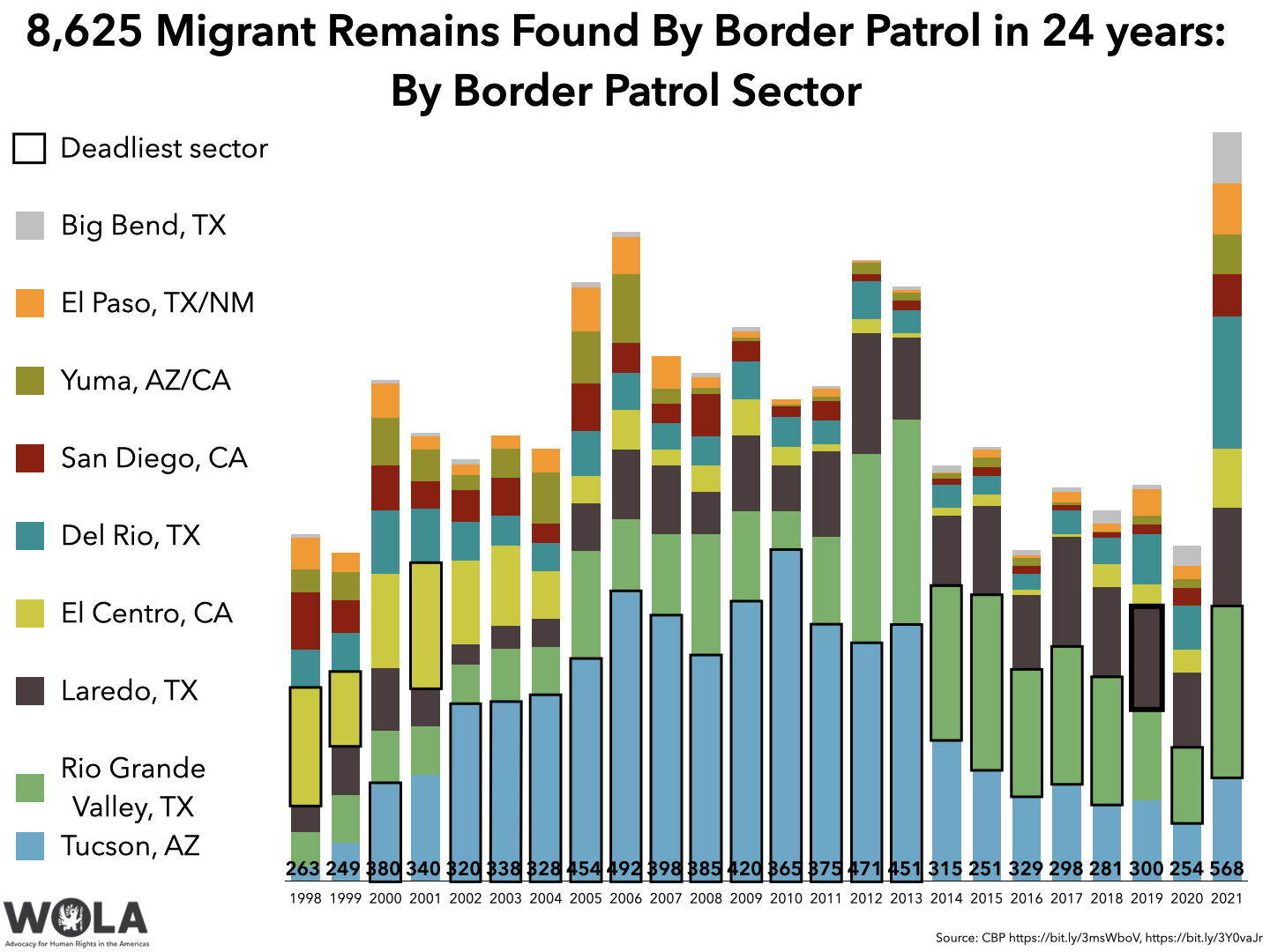

The largest number of remains, 27 percent of the total, was recovered in south Texas’s Rio Grande Valley Sector. Rio Grande Valley—where many migrants die 80 miles north of the border, seeking to avoid a longstanding Border Patrol checkpoint in Brooks County—led all sectors in every year between 2017 and 2021, except for 2019. That year, CBP recovered more remains in the adjacent Laredo, Texas Sector.

Of the 1,454 migrants whose cause of death could be determined, 41 percent passed due to “environmental exposure-heat.” 23 percent of deaths were “water related.” 5 percent were “motor vehicle-related,” 4 percent died of “environmental exposure-cold,” and 8 deaths were “train related.”

Of the 1,189 remains whose gender could be determined, 15 percent were of female migrants.

Of the 902 migrants whose age could be determined, 4 percent were between the ages of 0 and 17; 30 percent were 18 to 25; 32 percent were 26 to 35; 23 percent were 36 to 45; 8 percent were 46 to 55; and 3 percent were 56 and older.

CBP’s report recognizes that its “data are not all encompassing. These numbers may differ from other organizations that track similar data.” While no other organization is able to keep a count of remains encountered along the entire border, regional organizations that do, such as those in Arizona, routinely find a significantly higher number of migrant remains than CBP does, as the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted in an April 2022 report.

Also on February 6, CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) released an annual report on “CBP-involved deaths,” also covering 2021. That year, it documented “55 in-custody deaths, 53 reportable CBP-involved deaths, and 43 additional deaths that Appropriations staff requested OPR to review.”