With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Due to staff travel, we will publish next week’s Border Update in an abbreviated format.

WOLA’s March 31 Border Update reported a death toll of “39 or more people” from a March 27 fire in a Mexican government provisional migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez, just over the border from El Paso, Texas. On April 3, Mexico’s public security department increased the count to 40 deaths: one of the men injured in the fire died while being flown to a hospital in Mexico City.

Not including this 40th individual, whose nationality was not reported, the fatal victims include 18 Guatemalan migrants (most from the country’s Indigenous-majority highlands), 7 Venezuelans, 6 Hondurans, 6 Salvadorans, 1 Colombian, and 1 Ecuadorian.

As of March 30, 24 migrants were hospitalized in serious or critical condition: 10 Guatemalans, 7 Hondurans, 4 Salvadorans, and 3 Venezuelans. Mexico turned down a U.S. government offer to provide medical treatment to some of the injured in the United States, arguing that they were “too ill to be moved,” the Associated Press reported. Still, Mexico has since sought to fly some to specialized treatment in Mexico City.

Troubling details about the tragedy continue to emerge. “Multiple testimonies” indicate that the facility had no emergency exits or fire extinguishers in its detention area, the daily Milenio reported. Some of the detainees had been there for several days, or even since February, though the legal maximum is 36 hours. In the United States, relatives of the victims are complaining that the Mexican government is not responding to inquiries or helping with the complicated repatriation of remains.

Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, paid a visit to Ciudad Juárez on March 31, where he said that the tragedy “hurt me a lot, it damaged me.” As the President’s white van, with him in the passenger seat, drove through Ciudad Juárez’s central square, it was detained for several minutes as mostly Venezuelan migrants surrounded the vehicle. López Obrador “opened the window and took the hand of a woman who pleaded with him as others pushed letters into his hand and cried for justicia, or justice, for the migrants,” the El Paso Times reported. One migrant reportedly said to him, “Don’t do what the United States does,” to which he replied, “we are not the same, my love, don’t confuse us.”

A Mexican federal judge ordered the indictment, for homicide and intentional injury, of five people accused of involvement in the tragedy: three employees of Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM), one private security guard, and a Venezuelan migrant, Jeison Daniel Catarí Rivas, accused of setting fire to mattresses in protest, after guards allegedly said that the men in custody would be deported. “None of the public servants, nor the private security guards, took any action to open the door for the migrants who were inside where the fire was,” said a federal human rights prosecutor cited by the New York Times.

The INM has come under fire for the tragedy, especially after security camera footage showed personnel leaving the facility without opening the doors of a detention area filling with flames and smoke. While no source appears to have a current count, Pie de Página reported that in 2019, INM was managing 30 detention centers throughout Mexico, plus an unknown number of provisional facilities like the one in Ciudad Juárez.

“The majority of these centers,” the online journalism outlet continued, citing a network of human rights groups, “lack potable water in bathrooms or toilets, and are places subject to inclement weather where the food that is delivered, in addition to being scarce, is often rotten. …Private security personnel use threatening and abusive language with detainees, do not guarantee them the right to communicate with the outside world.”

The Mexican government’s public security secretary, Rosa Icela Rodríguez, said that the Ciudad Juárez provisional detention center will not reopen. Upon apprehension in the city, migrants will be taken to the Mexican federal government’s 900-capacity shelter, opened in 2019, where they are not confined.

Rodríguez added that Mexico’s federal government has canceled its contract with Grupo de Seguridad Privada CAMSA, a company that was providing security guards to INM detention centers in 23 of Mexico’s 32 states. She noted that INM had “ignored the presidential order to hire elements of the Federal Protection Service (SPF) instead of private security companies, arguing that they are cheap,” Milenio reported.

Other governments called for accountability for the tragedy. “El Salvador demands justice for this crime, which it considers a crime of the state,” Border Report cited Cindy Mariella Portal Salazar, El Salvador’s vice minister for migrant affairs, as stating, adding that “she is not satisfied with the arrest of five guards and INM officers.” A statement on Twitter from Honduras’s Foreign Ministry called for a “broad investigation” of Mexican authorities’ responsibility. The Central American web outlet ContraCorriente noted that three of Honduras’s six victims were young men from the same town in western Honduras: El Nuevo Porvenir, which was completely destroyed by Hurricane Mitch in 1998.

U.S. human rights groups and some reporting continued to note that the migrants’ presence in Ciudad Juárez was a result of U.S. migration policy, which has made it very difficult for people to request asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. All but two of the fire’s victims were from countries whose citizens are subject to immediate expulsion back into Mexico, without a chance to ask for asylum, under the Title 42 pandemic order.

The one means of making an appointment to ask for asylum from northern Mexico, the “CBP One” smartphone app, continues to be plagued by technical problems and a small number of available appointments. The CBS News program 60 Minutes featured the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border, documenting asylum seekers’ difficulties with CBP One and interviewing DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. CBP One issues were also the subject of an episode of Slate’s What’s Next TBD podcast. Those who fail to navigate the app remain stranded in Ciudad Juárez and other Mexican border cities.

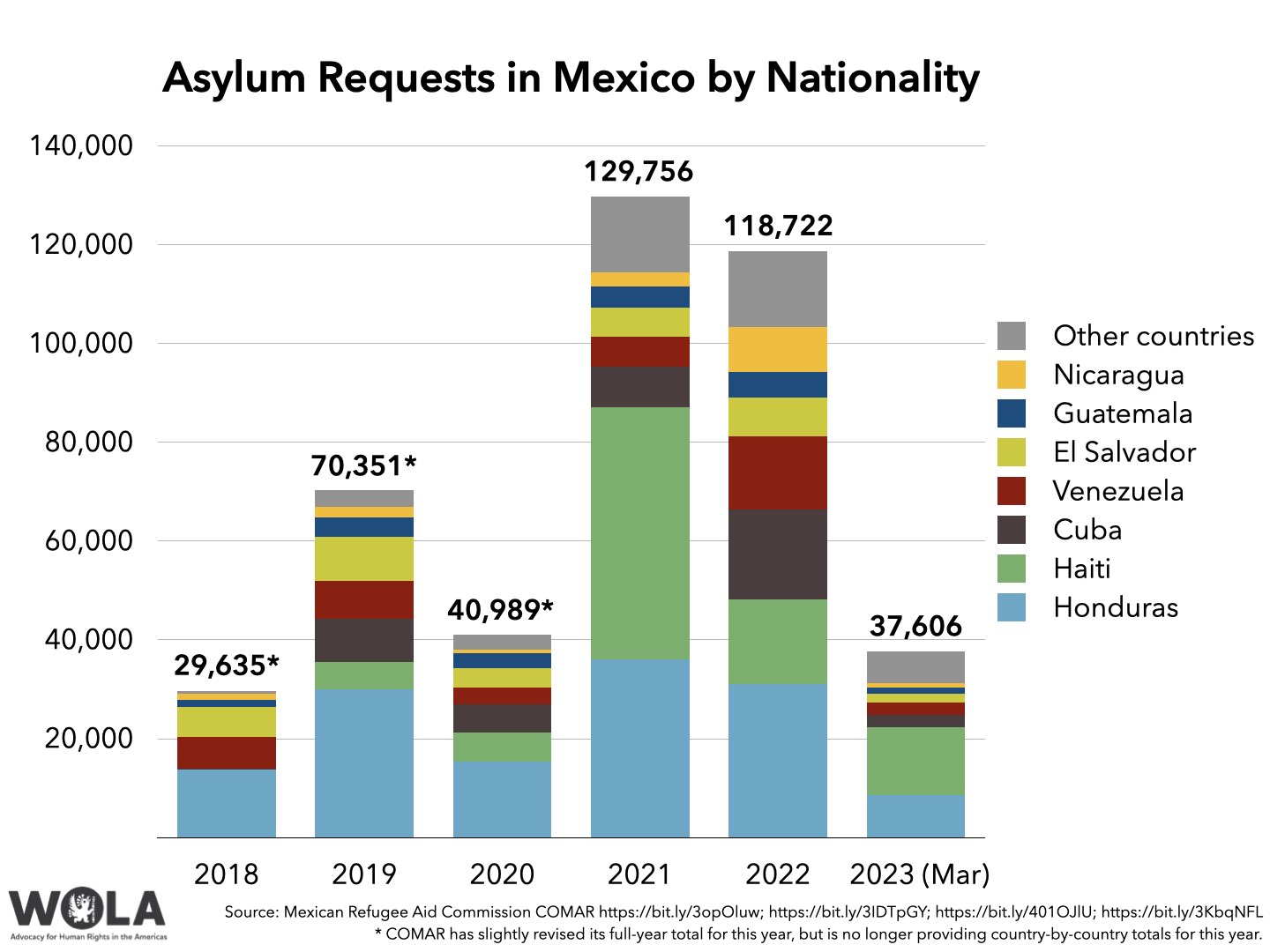

Mexico’s Refugee Aid Commission (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, COMAR), which operates the country’s asylum system, reported receiving 37,606 applications for asylum in Mexico during the first three months of the year. This is the largest number of asylum requests that Mexico has ever recorded during the first quarter of a year; if sustained over all of 2023 it would total over 150,000, a record by far.

Applications jumped from 6,497 in January, to 6,932 in February, to 8,993 in March. So far this year, applications from citizens of Haiti are the most frequent with 13,631 (In addition, COMAR lists 1,344 from Brazil and 1,302 from Chile, noting that most are children of Haitian citizens who had been residing in those countries). Honduras (8,620), Cuba (2,596) and Venezuela (2,547) follow. Of 7,369 requests that COMAR has managed to process so far this year, it has granted asylum in 69 percent of cases (5,104).

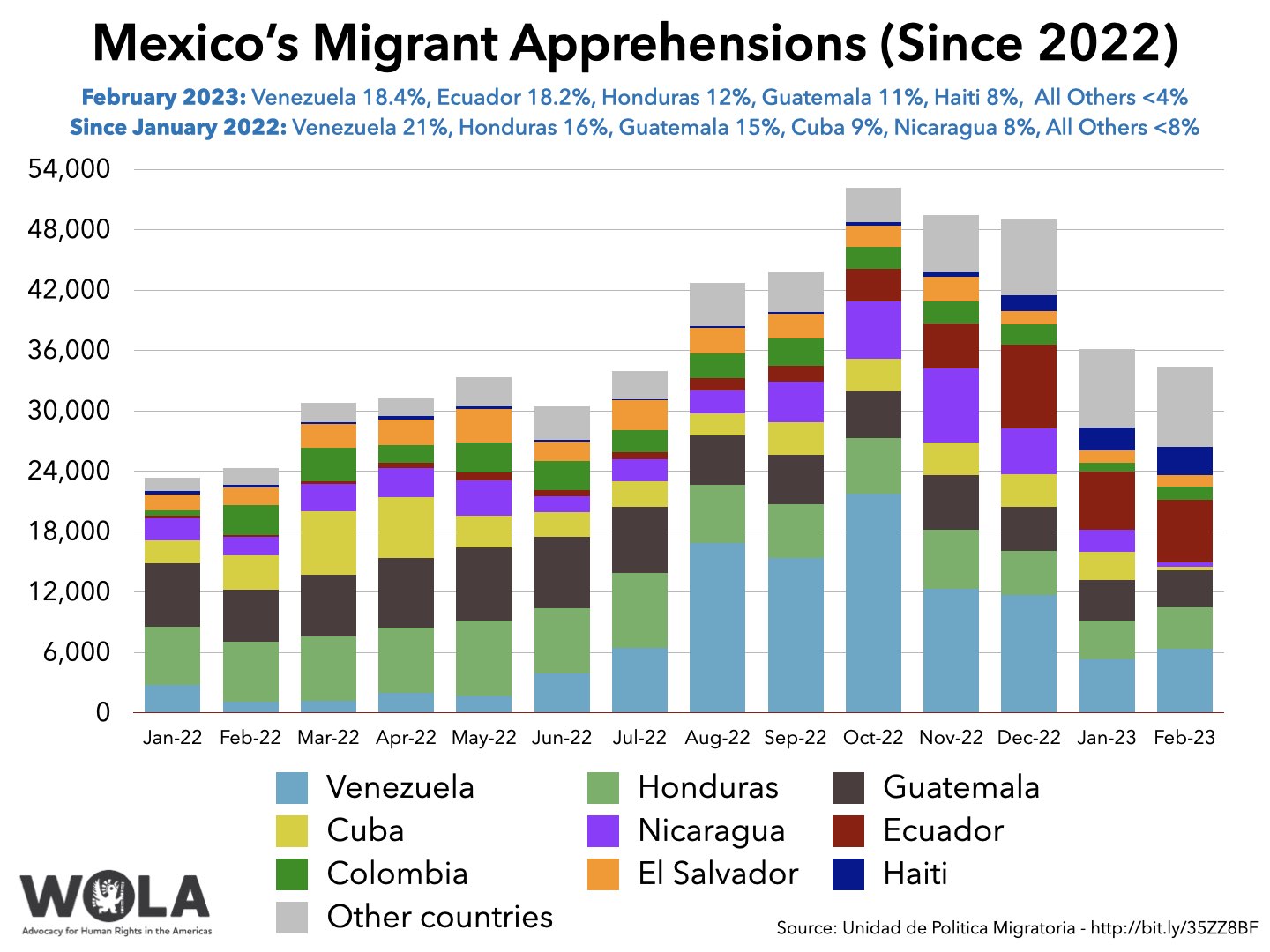

During the final days of March, Mexico’s Migration Policy Unit (Unidad de Política Migratoria) published data about authorities’ apprehensions of migrants in Mexico through February 2023. The number-one nationality of migrants apprehended in Mexico in February was Venezuela 6,331, barely edging out Ecuador (6,249), which is actually the number-one nationality for the 2023 calendar year so far.

Mexico’s apprehensions of Venezuelan migrants increased by over 1,000 over January, even though since October 2022, Venezuelans apprehended on the U.S. side of the border rarely get a chance to seek asylum: they are subject to Title 42 expulsion to Mexico. (In February, U.S. authorities encountered a majority of Venezuelan migrants at ports of entry, presumably with “CBP One” appointments.)

During the first two months of the year, Mexico has apprehended migrants from 101 countries. Enrique Lucero, the director of migration policy in the Tijuana mayor’s office, told Border Report that the city has seen an “ongoing flow” of migrants from Africa, mainly the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana and Somalia, who “are all taking the same route through Brazil, they’ll cross South America and then on to Mexico City and finally Tijuana.”

Mexican border cities, like Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, continue to host ever larger numbers of stranded migrants. Shelters are now so full in Ciudad Juárez, Border Report found, that Central and South American migrants—including entire families—are now living in abandoned buildings and on the streets. Desperation is so great that the slightest rumor—like a Facebook message on March 31—can cause large groups to cross the border at once. That day, more than 1,000 migrants, mostly from Venezuela, crossed the Rio Grande and sought to turn themselves in to Border Patrol on the mistaken belief that they would be allowed to enter.

Further south, Panama has yet to publish March data about migration through the treacherous Darién Gap jungle region. Preliminary reports indicate, though, that about 1,200 people per day migrated through the Darién region last month, which would put March 2023 on pace to be the third-heaviest month ever for Darién Gap migration.

The 9,683 minors who traveled through the Darién Gap in January and February were “the most recorded in a two-month period since these records have been kept,” according to UNICEF. The agency estimated that an average of five children per day are making the 60-mile journey unaccompanied.

The chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, Sen. Gary Peters (D-Michigan), visited Panama, including the Darién Gap region, on April 4.

Migration through the Darién Gap was the subject of an April 5 panel ( video) at Columbia University featuring Nadja Drost and Federico Ríos, two journalists who have transited this route alongside migrants.