With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Official reports and video released and divulged over the past week shed more light on two troubling mid-May fatalities involving Border Patrol: the May 17 death in custody of 8-year-old Panamanian migrant Anadith Danay Reyes Álvarez, and the May 18 shooting death of 58-year-old U.S. citizen and Indigenous community member Raymond Mattia.

Regional migrant processing centers, an initiative of the State and Homeland Security departments working with UN agencies, began accepting online applications in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. So far, the Centers’ scope appears to be more modest than the departments’ original announcements had indicated, with only a small number of nationalities able to access them, and capacity limits quickly saturated.

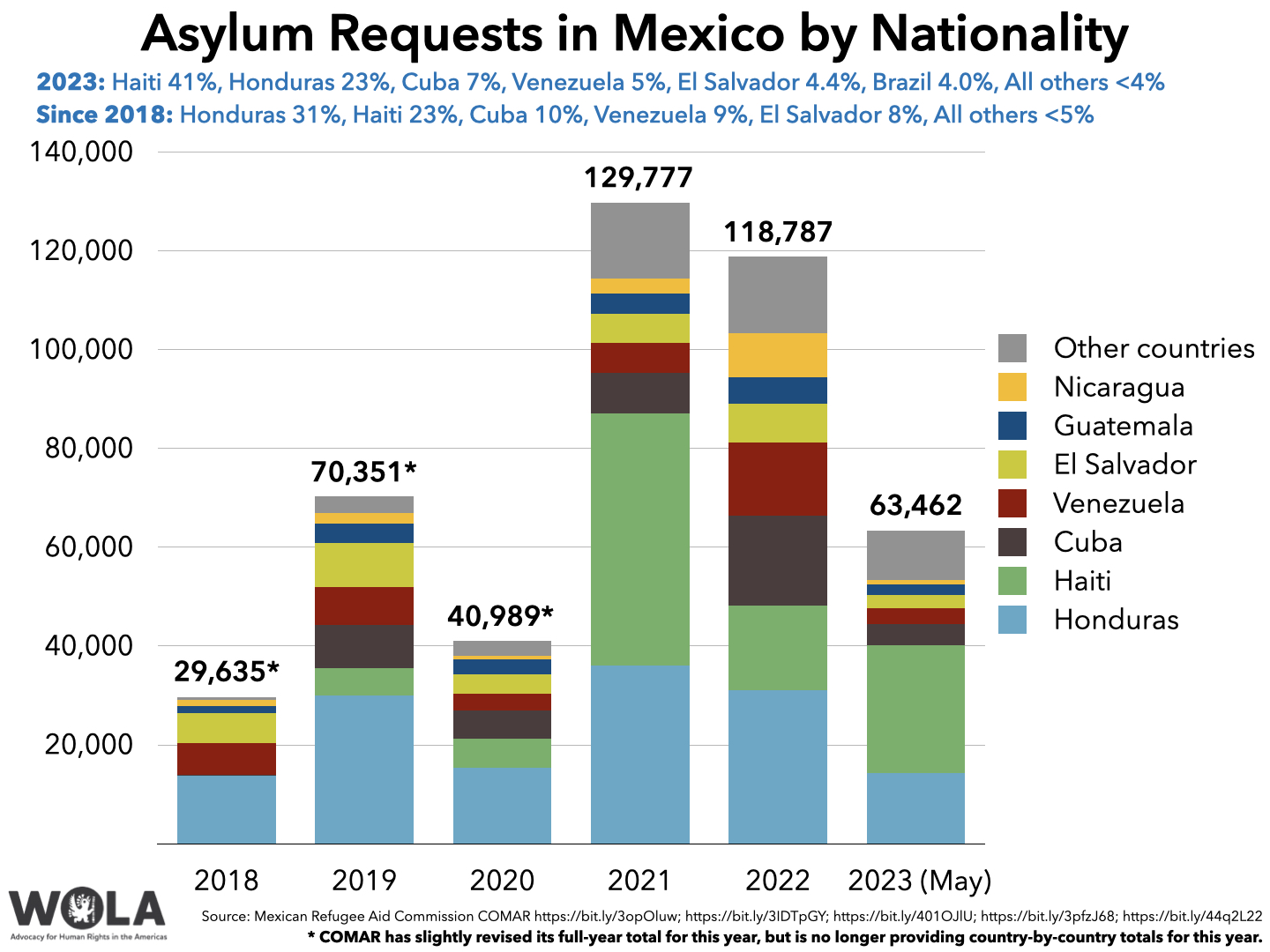

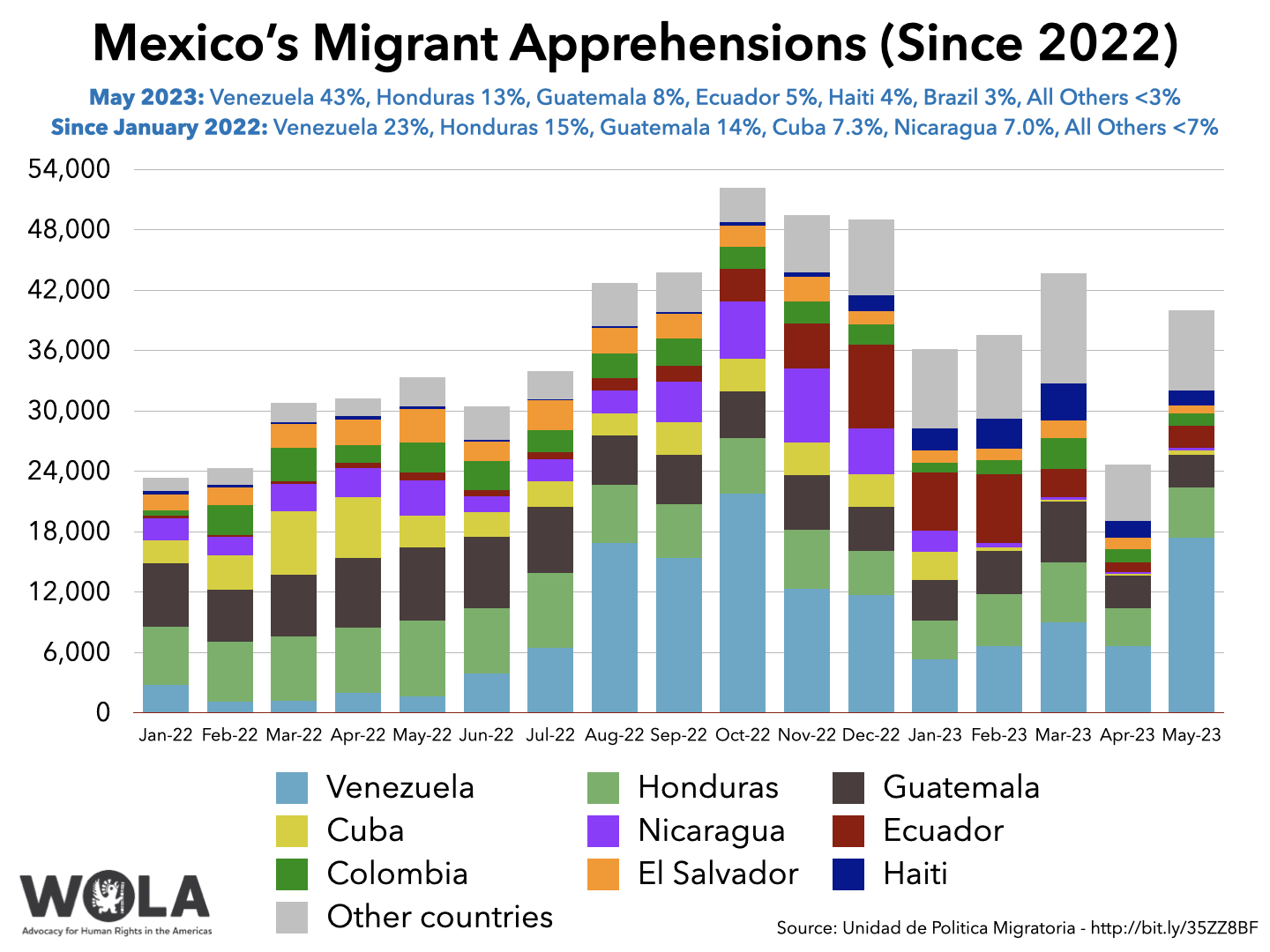

For Mexico’s authorities, May 2023—which included the final 11 days of the Title 42 policy—was the 10th-busiest month this century, with 40,020 migrant apprehensions from 99 countries. A large plurality of migrants, 43 percent, were Venezuelan. Haiti leads the nationalities of Mexico’s 63,463 asylum applicants so far this year, with 41 percent of the total.

Official reports and video released and divulged over the past week shed more light on two troubling mid-May fatalities involving Border Patrol: the May 17 death in custody of 8-year-old Panamanian migrant Anadith Danay Reyes Álvarez, and the May 18 shooting death of 58-year-old U.S. citizen and Indigenous community member Raymond Mattia.

On June 22, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP, Border Patrol’s parent agency) released edited body-worn camera footage depicting Raymond Mattia’s death. (The video contains heavy profanity and graphic violence.) At about that time, the Pima County, Arizona Medical Examiner’s autopsy report also became public.

The evidence confirms that three agents, shooting rapid volleys of bullets, hit Mattia nine times on the evening of the 18th, as he stood outside his home on the lands of the Tohono O’odham nation in southern Arizona. The video shows:

Mattia’s relatives say they know nothing about “shots fired” in the area that evening, and that Mattia “thought the agents were there to respond to his previous call about migrants on his property,” NBC reported. Family members told the Intercept that they are perplexed about why agents decided to zero in on Mattia’s home. “The dispatcher states that they couldn’t pinpoint where the shooting was coming from, but yet, when they are there at the rec center, they’re coming straight to my uncle Ray’s house, with their guns drawn,” said Mattia’s niece, Yvonne Nevarez.

Mattia appears to have had a complicated past relationship with Border Patrol. The Intercept noted that Mattia, a member of his village’s community council, “had been outspoken against the corruption he saw on the border, including corruption involving border law enforcement.” Amy Juan, a leader of the Tohono O’odham Nation in southern Arizona and northern Sonora, told the Border Chronicle podcast that Mattia had “been vocal, not just now, but in the past and recently, about the activity happening that he’s seen in his community, namely, involving Border Patrol. Corruption, and being involved in illegal activities there.” On an episode of the Border Patrol union-affiliated podcast, meanwhile, National Border Patrol Council Vice President Art del Cueto was quick to point out that Mattia had a prior arrest record.

The agents who fired their weapons are currently on leave with pay, as is standard in such use-of-force incidents. CBP’s most recent statement notes that the incident “is being investigated by the Tohono O’odham Police Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation and is being reviewed by CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR).” Once these investigations conclude, CBP’s National Use of Force Review Board will review the incident and make disciplinary recommendations, if any.

In fiscal year 2021, the last year for which data are available, this Review Board and local review boards declined to issue sanctions in 96 percent of the 684 cases they reviewed. Of the other 24 cases, 11 ended up with counseling for the agents involved, and the other 13 remained under investigation or pending action as of April 2022.

“There’ll be an investigation, an assessment of the force used, and we are going to look at tensions in the community,” Gary Restaino, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Arizona, said on June 23. Frank Figliuzzi, a former civil rights supervisor for the FBI in San Francisco, shared with NBC News his belief that the agents may not be disciplined “given that officers were responding to a ‘shots fired call,’ the way Mattia pulled out his phone, and the darkness of the environment, among other factors.”

The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times reported on internal Department of Homeland Security (DHS) documents finding fault with CBP’s care for medically fragile migrants in the agency’s custody, following the May 17th passing of Anadith Reyes. That day, her family’s ninth in Border Patrol custody and the day after measuring a 104.9 degree fever, Reyes—who had a documented history of heart problems and sickle-cell anemia—died of influenza in Border Patrol’s Harlingen, Texas station holding facility.

Reyes’s parents—most recently in an interview with ABC’s GMA3 program, have said that they asked agents and contract medical personnel many times to give Anadith more urgent care. Her mother reiterated that personnel were not interested in reviewing the medical documents that she had brought with her. “She says she felt like medical personnel thought she was lying about how sick her child was feeling,” according to ABC. “She says Anadith told the staff ‘I can’t breathe from my mouth or my nose.’” CBP’s initial review of what happened upholds the family’s account of refusals of multiple requests for more urgent assistance.

The Washington Post reviewed a June 8 internal memo from DHS acting chief medical officer Herbert O. Wolfe that found the Harlingen Border Patrol station “lacked sufficient medical engagement and accountability to ensure safe, effective, humane and well-documented medical care.” The memo, according to the Post’s Nick Miroff, “describes an ad hoc system with little ability to manage medical records, poor communication among staff and a lack of clear guidelines for seeking help from doctors outside the border agency.”

In a response to the memo, CBP’s “senior official performing the duties of the commissioner,” Troy Miller, said that the agency is reviewing its medical record-keeping system and has told its medical contractor to “take immediate action to review practices and quality assurance plans to ensure appropriate care.” That contractor, Loyal Source Government Services, “received a $408 million medical services contract from CBP in 2020,” the Post reported.

The Los Angeles Times obtained documents from DHS’s Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO) indicating that officials at one of the Texas CBP detention facilities where Anadith’s family was held “were complaining about the facility’s ‘overuse of hospitalization.’” A May 22 memo reported by the Times’s Hamed Aleaziz noted that the staff of CBP’s Donna, Texas processing facility “had a ‘tendency to send migrants to the hospital for things that could easily be treated on location,’ the investigators wrote.” Days earlier, agents refused Anadith Reyes’ parents’ repeated pleas for an ambulance and hospital care.

Faced with these and other allegations of abuse and unprofessional conduct, on June 22 CBP designated its deputy commissioner to be its “Chief Integrity Officer,” while issuing a 20-page “Integrity and Accountability Strategy” document. The document, which lists a series of principles and general goals, seeks to apply a “holistic approach” that “focuses on influencing and enhancing a culture always reflective of CBP’s core values.” It proposes greater promotion of “core values” within the agency, more transparency to “preserve public trust,” and “accountability for misconduct and mismanagement.”

On April 27, the Departments of State and Homeland Security, billing it as a “historic move,” announced their intention to “Open Regional Processing Centers Across the Western Hemisphere to Facilitate Access to Lawful Pathways” for migration. These Centers would “be established in several countries, including Colombia and Guatemala, in the region.” On May 10, DHS and the Department of State revealed that their plans involved opening “about 100” such Centers, with “over 140 Federal personnel, including from DHS and State, and personnel from the International Organization on Migration and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.” Colombia’s ambassador to the United States said that “more than a dozen” Centers would open in his country.

At these locations, managed principally by those UN agencies, would-be migrants who had made appointments online would participate in interviews and be considered for legal pathways to migration in the systems of the United States, Canada, and Spain. U.S. pathways include temporary work visas, temporary humanitarian parole for four countries’ citizens, refugee admissions, and family reunification for some countries’ citizens—but not asylum, which requires that the applicant be on U.S. soil.

In recent days, Centers began accepting online applications in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Guatemala at a new website, movilidadsegura.org. So far, the Centers’ scope appears to be more modest than the State and Homeland Security Departments’ original announcements had indicated. The number of nationalities whose citizens may access the Centers is limited, and they already appear to be confronting capacity issues.

The Centers are unavailable to would-be migrants from other countries—including Colombians in Colombia—and to all who arrived after those dates.

The “movilidadsegura.org” website notes that its “online form will occasionally be temporarily unavailable to allow for application processing.” The Colombia site began showing an “Online applications for Movilidad Segura are temporarily closed” message within hours of launching on June 28, apparently due to saturated capacity. That had already happened with the Guatemala Centers, which stopped accepting new applications within days of launching an online form on June 12. Guatemala’s Foreign Minister told the Voice of America that he does not know when the Centers’ form will go online again. That, he said, is up to the U.S. government.

In part, the Regional Centers’ less ambitious scope results from the nature of initial roll-outs: the Centers are operating on something like a pilot basis to determine what adjustments are needed. “We look forward to ramping up these efforts and working with additional countries to set up Safe Mobility Offices in the region,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on June 23.

The Mexican government’s Migration Policy Unit released its count of migrants apprehended in the country during May 2023. For U.S. Border Patrol, May—the month during which the U.S. government’s Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy ended, on the 11th—was the 24th-heaviest month this century: agents apprehended 169,244 migrants. For Mexico’s authorities, May was the 10th-heaviest month this century, with 40,020 migrant apprehensions.

Mexican authorities apprehended migrants from 99 countries last month. 43 percent came from Venezuela, followed by Honduras (13 percent), Guatemala (8 percent), Ecuador (5 percent), and Haiti (4 percent). May’s apprehensions number was up sharply from April, when—in the wake of a tragic late-March fire that killed 40 migrants at a Ciudad Juárez detention facility, Mexican forces’ apprehensions fell to 24,691.

13,647 migrants applied for asylum in Mexico, the most in a single month so far this year, according to the Mexican government’s Refugee Aid Commission (COMAR). So far this year, 41 percent of Mexico’s 63,462 asylum applications have come from Haitian citizens (plus another 8 percent from Brazil and Chile, most of whom are children of Haitian migrants who were born in those countries). Applications from Haiti jumped by about 7,000 from April to May, making up more than half of last month’s demand. 23 percent of applications came from Honduras, followed by Cuba (7 percent), Venezuela (5 percent), and El Salvador (4 percent).