With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Anecdotal information points to an increase in migrant deaths in the U.S.-Mexico border zone, amid skyrocketing early summer temperatures in the southern United States and Mexico. Border Patrol reported recovering 13 human remains in the past week. A child died of apparent heat exposure in Arizona, and an infant was among the remains of four people recovered from the Rio Grande in a 48-hour period in Texas.

The number of migrants apprehended by Border Patrol remains much lower than before the end of Title 42, while CBP has steadily increased the number of asylum-seeking migrants who may obtain daily appointments at ports of entry. Further south, northern Mexico border cities appear to have a somewhat smaller migrant population, but numbers may be increasing in southern Mexico. Migration through Honduras increased in June, but decreased in Panama’s Darién Gap.

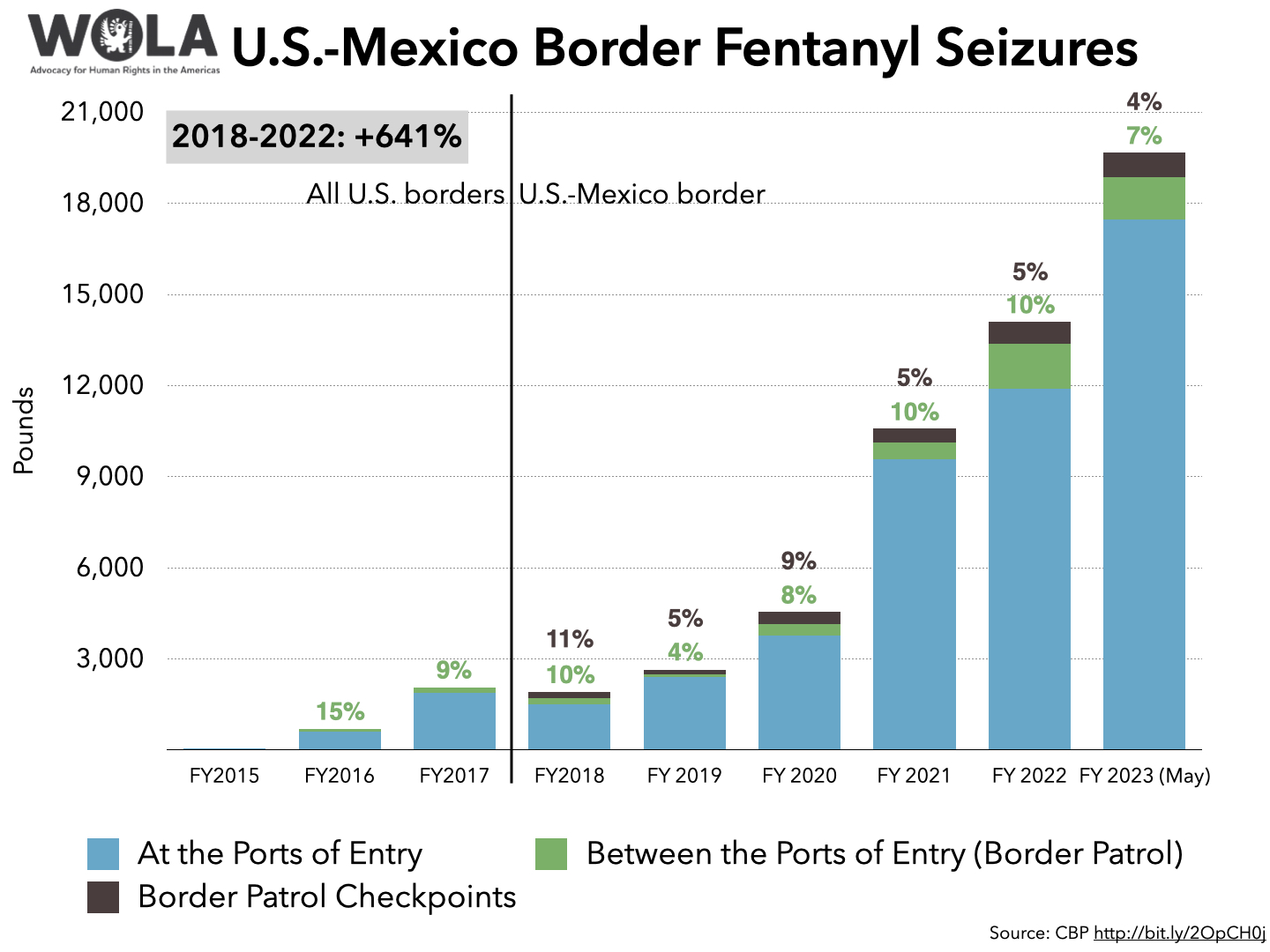

So far in fiscal year 2023, U.S. border authorities have seized about one-quarter less heroin, methamphetamine, and marijuana than they did during the same period a year earlier. Cocaine seizures are up slightly, though, and fentanyl seizures are up 169 percent. Supplies of the potent opioid appear to be glutted, and the U.S. government stepped up interdiction with a “surge” operation between March and May.

Jet-stream fluctuations left much of the southern United States and northern Mexico trapped in an early summer “heat dome” for about two weeks in June. Reports are pointing to severe consequences for U.S.-bound migrants, both those who attempt to walk through deserts to avoid detection, and those waiting in northern Mexico, often in squalid conditions, for appointments to present themselves to U.S. authorities to seek asylum.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported receiving a distress call on June 15 from a woman who was attempting to migrate through southern Arizona’s deserts with her two children. Somewhere outside Tubac, a town about halfway between Nogales and Tucson, her 9-year-old son began experiencing seizures. “The female migrant stated her son did not have prior existing medical issues and believed the heat contributed to his medical complications during their walk.” Despite being aerially evacuated, the boy died on June 16.

It used to be unusual to see families attempting to migrate through the desert, seeking to avoid apprehension. Further west, in Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Laurie Cantillo, a board member and volunteer for the Arizona-based organization Humane Borders, told NBC News that she came across “a mother with an infant strapped to her back, neither wearing sun protection” walking in 115-degree heat (46 degrees Celsius).

Just west of El Paso lies Sunland Park, New Mexico, a border municipality in the Chihuahuan Desert. In all of 2022, the Albuquerque Journal reported, the remains of 16 people attempting to cross the border were found in Sunland Park, a figure that combines deaths from heat exposure with deaths by falls from the border wall. In May and June 2023 alone, the number of recorded deaths in Sunland Park is 13, including 5 remains in a 4-day period during the June heat wave.

On the border’s eastern edge, in the Mexican city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas across from Brownsville, Texas, humanitarian workers worry about conditions in a makeshift tent camp. As many as 2,000 asylum seekers are waiting there in the blistering heat for a chance to seek asylum at a port of entry using the “CBP One” smartphone app. On July 5, Reuters published a detailed article and photo essay about conditions at the Matamoros camp, which now extends for a mile along the riverfront. Sister Norma Pimentel of the Texas-based Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley told NBC that many migrants in the camp “are fed up waiting to book appointments.” Efforts to replace the encampment with a more adequate facility are “so disorganized right now,” Pimentel lamented.

“Last week alone,” Border Patrol’s new chief, Jason Owens, tweeted on July 5, the agency “recovered 13 dead migrants” with heat “the leading cause,” and reported 226 heat-related rescues.

Though not necessarily heat-related, Texas’s state Department of Public Safety meanwhile reported recovering the bodies of four people from the Rio Grande in the vicinity of Eagle Pass: two on July 1, one on July 2, and another on July 3. The victims included an infant found with “an unresponsive woman.” None of them possessed identifying documents, so their identities and nationalities are unknown. Two other migrants were pulled from the river alive during those days.

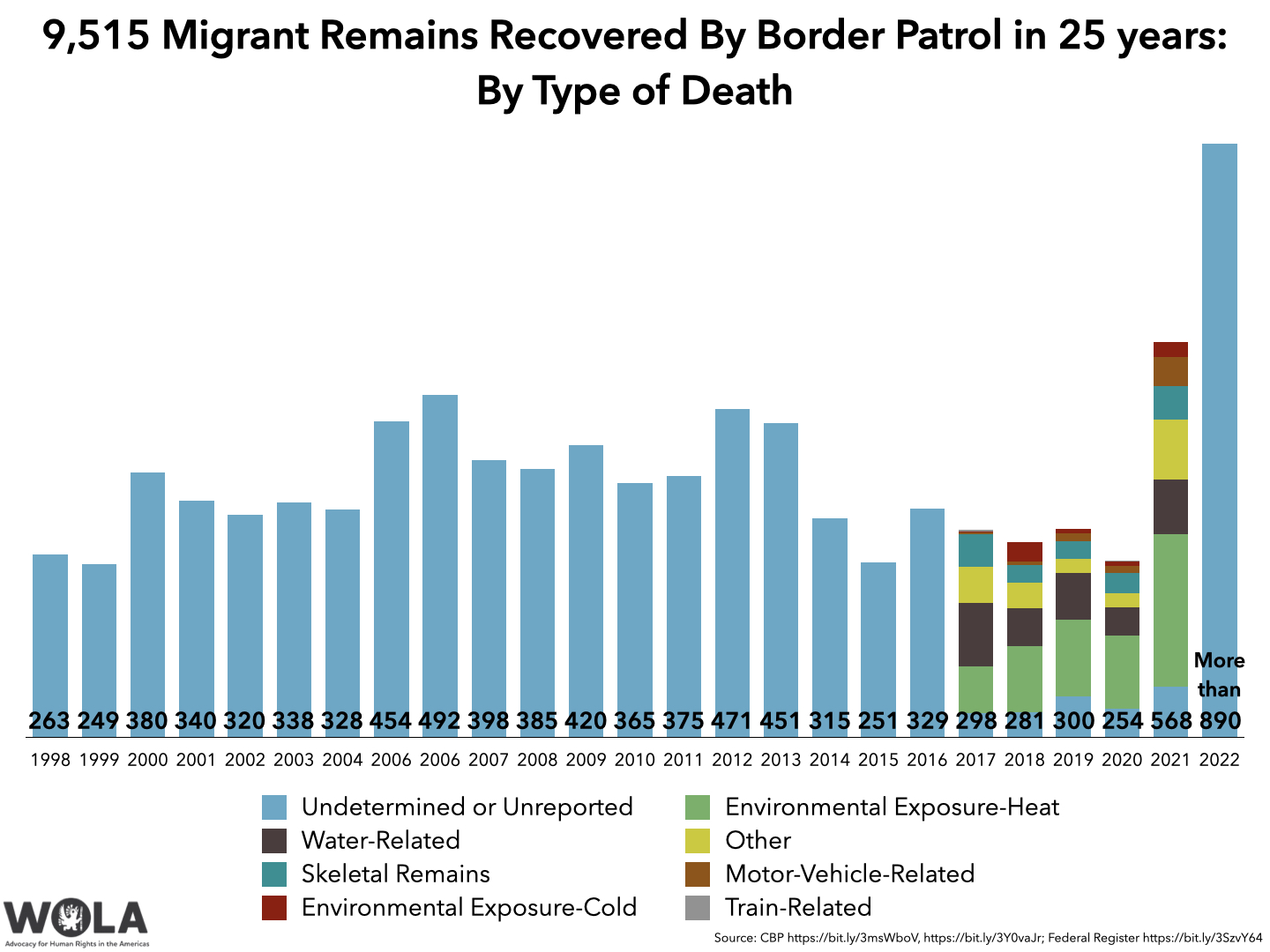

It is not yet clear whether border-zone deaths of migrants in 2023 are on track to exceed the record-breaking levels of 2021 and 2022. “In an emailed statement,” NBC reported, CBP “said it has recorded recent deaths but did not provide a number.” We still await CBP’s count of remains recovered in fiscal year 2022 (October 2021-September 2022), which the agency was required by law to report by December 31, 2022. The unofficial number in the below chart, “more than 890,” comes from the February 2023 text of the Biden administration’s rule limiting access to asylum for people who didn’t first seek it in other countries.

Local humanitarian organizations routinely report higher totals of deaths than CBP does in the regions they cover. For its part, the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Missing Migrant Project counted 666 instances of missing migrants along its “U.S.-Mexico border crossing” migration category in the 2022 calendar year, and 222 so far in 2023.

A July 3 New York Times analysis noted that the number of migrants apprehended by authorities on the U.S. side of the border remains roughly half of what it was before May 11, when the Biden administration replaced the Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy with a new rule limiting many migrants’ access to asylum.

The U.S. Border Patrol Chief’s most recent “Week in Review” post to Twitter, covering an 8-day period ending June 29, reported an average of 3,542 migrant apprehensions per day. That was the largest average the Chief’s account had reported since May 19, but still less than half of the more than 7,000 per day reported during the first two weeks of May.

(As Border Patrol does not manage official ports of entry, the agency’s numbers do not include the 1,000-plus people per day, discussed below, who are now securing CBP One appointments at the border since Title 42 ended.)

The Times relayed U.S. border officials’ view that the lull in migration is probably temporary. “Officials believe that migrants have been in a wait-and-see mode since May 12,” as they see what happens to others who attempt to cross.

Asylum-seeking migrants are waiting in Mexico for appointments at ports of entry using the CBP One smartphone app. On June 30, CBP announced a further expansion in the daily number of appointments, to 1,450—up from 1,250 in June, 1,000 between May 12 and May 31, and an average of about 740 during the last few months of the Title 42 period. CBP’s statement reported that “more than 49,000 noncitizens have presented at Southwest border ports of entry through scheduled CBP One™ appointments for inspection” between May 12 and June 23.

It remains unclear how long-lasting this reduction in migration will turn out to be. Clues can be found by looking at U.S.-bound migration in countries further south. “I am confident there are a lot of people moving into the hemisphere, mostly headed this way,” CBP Acting Deputy Commissioner Benjamine “Carry” Huffman told a House Homeland Security Subcommittee hearing on June 6. “The exact numbers, it’s hard to tell where they’re going to stop. But yes, they are moving.”

While further increases in migration are likely, the probable timing is unclear and the trends to the south are contradictory. In northern Mexico, for instance, many migrants are awaiting a chance to secure a CBP One appointment, but anecdotal data seem to point to an easing of the overall migrant population.

In Ciudad Juárez, Border Report noted that the municipal government shut down a tent shelter set up after a March 27 fire in a migrant detention center that killed 40 people. It is no longer needed, Mayor Cruz Pérez Cuéllar said: “Occasionally we get a large group of migrants that the government of the United States sends back (to Mexico) but (the flow) has gone down a lot. All of the other shelters in the city have plenty of space.” The Mayor cautioned, though, that it is impossible to know how many migrants are in the city: “There are not as many as before but we can only tell you how many are at the shelters; we don’t know how many are on the streets. Nobody knows.”

One reason that Juárez and other Mexican northern-border cities may have fewer migrants right now is that Mexico’s government has been actively working to prevent migrants from reaching the northern-border zone. Authorities are issuing fewer documents allowing people to travel throughout the country, and when the U.S. government deports Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, or Venezuelan migrants into Mexico under the new post-Title 42 arrangement, Mexico’s government has been flying many of them to the southern part of the country.

Mexico’s northern border cities remain dangerous for migrants. Twenty-two border-zone NGOs alerted that kidnappings and extortions of migrants are increasing in the northern states of Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, Durango, and Sonora. Kidnappings often occur as migrants attempt to board northbound buses. A “collaboration between authorities, bus companies, and organized crime” is facilitating the increased preying on migrants, Ciudad Juárez’s La Verdad reported.

In southern Mexico, migration trends are different: numbers of arrivals appear to be increasing. IOM officials told EFE “that the northbound flow of migrants has returned to its previous level after falling briefly in May.” From Mexico’s southern-border city of Tapachula, activist Irineo Mujica of the pro-migration group Pueblo Sin Fronteras confirmed to EFE that numbers are increasing.

Further south in Honduras, where the government publishes recent statistics, migration numbers are also increasing. The count of “irregular” migrants registered with the government points to a near-total recovery of early-May migration levels. Honduras measured 918 migrants per day during the first 10 days of May, 51 percent of them from Venezuela. That dropped to 769 during the remainder of May, but recovered to 892 per day in June, when 26,757 people registered with the government to obtain a free five-day travel document.

Of June’s total in Honduras, 47 percent were from Venezuela, followed by Cuba (12 percent), Ecuador (11 percent), Mauritania (7 percent), Haiti (5 percent), and China (4 percent). Honduras’s “irregular migration” totals do not include citizens of Nicaragua, who may travel through the country without a passport.

In Panama, migration through the treacherous Darién Gap region appears to have diminished in June. While Panama’s government has yet to publish full official statistics, a statement from the country’s migration authority and data reported in the Venezuelan publication Tal Cual and elsewhere point to 29,722 people migrating through the Darién jungles last month.

While still an unimaginably large number for such a remote and dangerous region, the June Darién Gap total is about one-quarter fewer people than Panama measured in March (38,099), April (40,297, which may have been revised upward), and May (38,962). The Mexican activist Mujica, speaking to EFE, blamed the drop on heavy rains in the Darién region, though migrants’ post-Title 42 “wait and see” posture may also be a factor.

Of June’s Darién Gap-region migrants, about 18,460—62 percent—appear to have been Venezuelan. While the proportion is similar to recent months, the number of Venezuelan migrants in June was about 8,000, and 30 percent, fewer than in May.

In all, 201,167 people migrated through the until-recently impenetrable Darién Gap during the first 6 months of 2023. The full-year record of 248,284 migrants, reached in 2022, is virtually certain to be surpassed within a few months.

Fifty-one percent, or 103,028, were Venezuelans, followed by citizens of Haiti (33,553), Ecuador (25,925), China (8,964), and Colombia (6,489).

The June decline in the Darién Gap, while steeper than what Honduras has recorded, is smaller than the drops noted in U.S. Border Patrol data. A steep drop at the U.S. border, combined with less-steep drops further south on the migrant route, probably means that the population of migrants bottled up between Panama and the U.S. border—mostly in Mexico—is increasing.

Comparing CBP’s border-zone drug seizure data for the first eight months of fiscal year 2023 (October-May) with the same period in fiscal 2022 reveals a sharp disparity across different types of drugs:

Seizures of methamphetamine, marijuana, and heroin are down by more than one quarter year-over-year. Seizures of cocaine are up 13 percent, at a time of record production in the Andes. But the big outlier is fentanyl: with nearly 20,000 pounds seized, U.S. authorities have already shattered their full-year record for border-zone fentanyl seizures (14,105 pounds in fiscal year 2022), and are close to tripling last year’s pace.

The reasons for the increase are an overall glut of the supply of the potent, hard-to-detect opioid, which sells on U.S. streets for as little as $2 to $3 per dose. U.S. authorities also stepped up interdiction efforts this year: a “surge operation” that the Justice and Homeland Security Departments called “Operation Blue Lotus” brought an increase in seizures between March 13 and May 10, 2023.

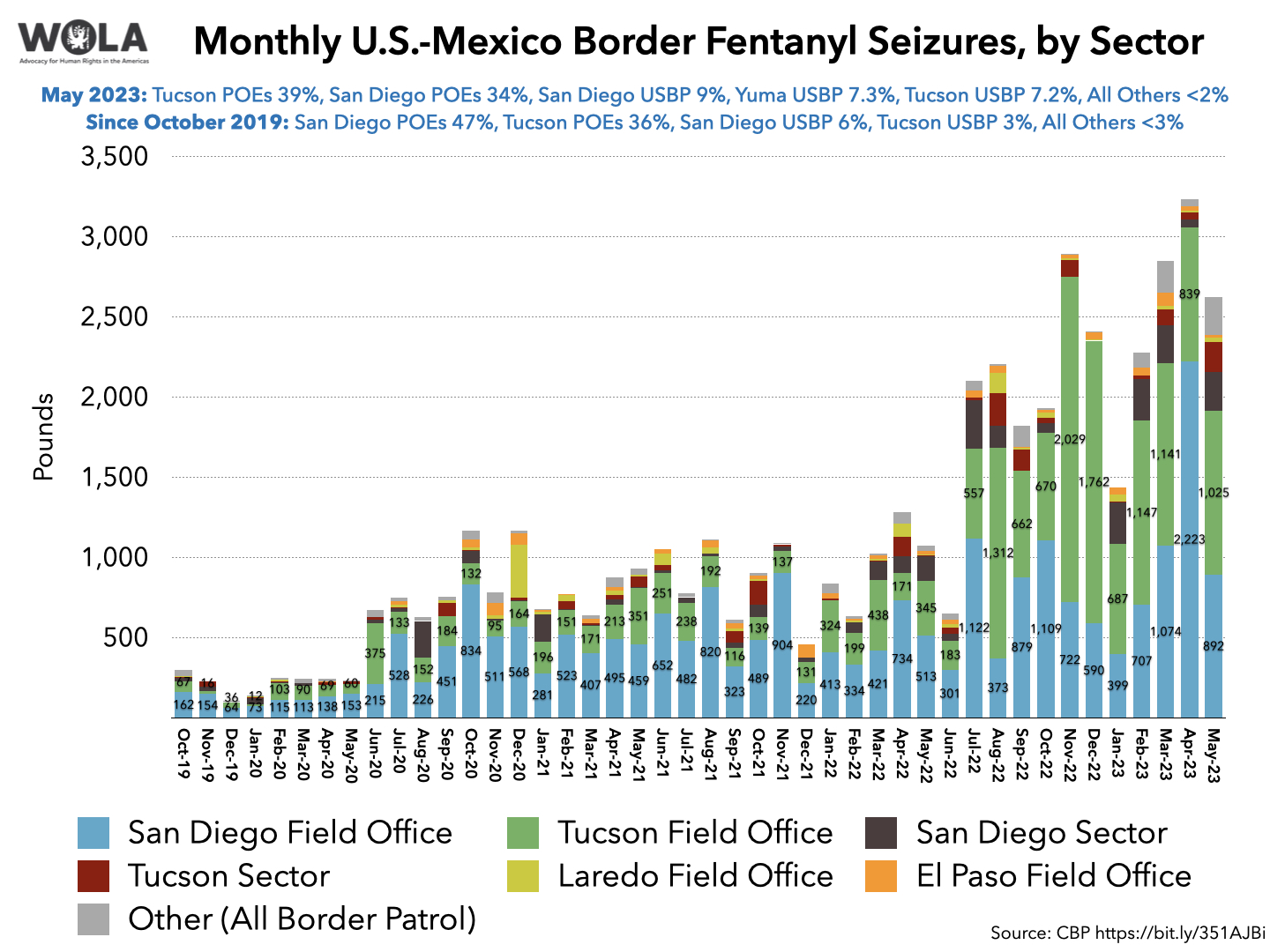

The epicenter of fentanyl smuggling appears to have shifted since mid-2022 from California to Arizona, whose border ports of entry (green on the below chart) now usually account for the largest share of seizures. In May, more than half of fentanyl seizures took place at ports of entry, or territories where Border Patrol operates, in Arizona.

CBP and Border Patrol continue to seize the overwhelming majority of drugs, except marijuana, at land-border ports of entry and vehicle checkpoints. Relatively little gets seized in the areas between ports of entry where Border Patrol operates.

Between October 2022 and May 2023:

Seizure data, of course, only reflects what U.S. border authorities are able to detect. “The 9,000 pounds that they’re touting [in the San Diego area], what fraction is that of the total amount?” asked David Shirk, director of the University of San Diego’s Justice in Mexico Program, interviewed by iNewsource. “We’re catching only a fraction and probably a very small fraction of the total amount of fentanyl that’s moving across the border.” Shirk noted that CBP’s data on “pounds seized” only reports the weight of the fentanyl pills, which include a large amount of inert ingredients since a potentially lethal dose is only about 2 milligrams. The seized drugs’ purity is unknown.