With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

An internal email from a Texas state policeman shed alarming light on the state-funded border security crackdown in Eagle Pass. Migrants are being injured by spools of concertina wire, and local authorities appear to be under orders to refuse humanitarian aid and make them swim back to Mexico in a notoriously dangerous segment of the Rio Grande.

In June, the first full month after the Title 42 pandemic policy ended, U.S. border authorities’ encounters with migrants dropped significantly. The number processed at ports of entry, however, increased to a record level, amid a jump in appointments granted using the “CBP One” smartphone app.

A court in Oakland, California, heard arguments about the Biden administration’s controversial rule limiting access to asylum, which went into effect upon Title 42’s termination. The rule denies asylum to most non-Mexican migrants who fail to make appointments at ports of entry and don’t first seek protection elsewhere along the way. Litigants and migrants’ rights defenders contend that the rule violates U.S. law and endangers migrants waiting in Mexican border cities.

The Houston Chronicle and Hearst Newspapers shared an internal e-mail from Texas State Trooper Nicholas Wingate, a medic assigned to Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s (R) state-funded border security crackdown in Eagle Pass, along the Rio Grande a few hours from San Antonio. It contains troubling revelations—now being confirmed by additional sources—of harm done to migrants by state personnel, apparently on the orders of superiors.

In that part of the border, Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) police and state-funded National Guardsmen have strung miles of razor-sharp coils of concertina wire along the riverbank and shallows. As covered in WOLA’s July 14 Border Update, they are also building a 1,000-foot floating “wall” of buoys in the middle of the river in front of downtown Eagle Pass.

Among recent results of these state operations, from Wingate’s e-mail (with excerpts in quotes):

“Due to the extreme heat, the order to not give people water needs to be immediately reversed,” Wingate wrote, adding: “I believe we have stepped over a line into the inhumane.”

The Houston Chronicle had already reported on the federal U.S. Border Patrol’s concern that the concertina wire would complicate rescues. On June 30, Fox News footage showed Border Patrol agents having to use shears to cut through the wire to reach migrants in the river.

Since 2021, Eagle Pass has been a prime crossing point for people seeking to turn themselves in to U.S. authorities and ask for asylum in the United States. It is also a treacherous section of the Rio Grande. In the roughly 75 miles of riverfront of Texas’s Maverick County—which includes Eagle Pass—the sheriff’s office has counted 103 drownings since 2022, according to the New York Times. That includes the July 1 death near Eagle Pass of a Guatemalan woman, her infant daughter, and another child whose body was never recovered.

The Texas state government issued a denial, stating that “no orders or directions have been given under Operation Lone Star that would compromise the lives of those attempting to cross the border illegally.” Texas DPS told The Hill, “There is not a directive or policy that instructs Troopers to withhold water from migrants or push them back into the river.”

Emerging evidence, however, points to the issuance of orders compelling behavior that endangered migrants. According to the New York Times, three other officers have corroborated that “there were explicit orders to deny water to migrants and to tell them to go back to Mexico. Three said they had been told by supervisors that troopers were not to inform the Border Patrol when migrants were in the water or at the Texas riverbank.”

A Texas DPS text message addressed to sergeants, obtained by the Times, read: “Can you please push out a message to your troopers. They are NOT to call BP when they see a group approaching or already on the bank.” The text, the Times added, “directed officers to tell migrants to ‘go back to Mexico’ and to cross the border at one of the international bridges.” To go “back to Mexico” would mean swimming back across a dangerous stretch of river.

A migrant interviewed by the Times showed wounds on his foot from stepping on concertina wire that Texas personnel had submerged in the river’s shallows, causing blood to gush through his tennis shoe. Another witnessed a woman caused “to hit her face on a spike, leaving a gash on her forehead” after a Texas agent roughly pulled a blanket off of a coil of wire at the riverbank, as people were climbing over it.

Further evidence indicates that officials were aware that endangerment of migrants was occurring, and worsening. Texas DPS director Steve McCraw sent an internal e-mail over the July 15-16 weekend, with photos of wounds, noting “that the razor wire had led to an increase in injuries for migrants.” In a July 17 report, USA Today found that, at an Eagle Pass migrant respite center, “the migrants who do stagger in often have slashes from the razor wire.”

Reactions to the revelations have come from many quarters.

On July 18 U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) released data about migration at the U.S.-Mexico border updated through June 2023, the first full month since the Title 42 expulsions policy’s May 11 termination.

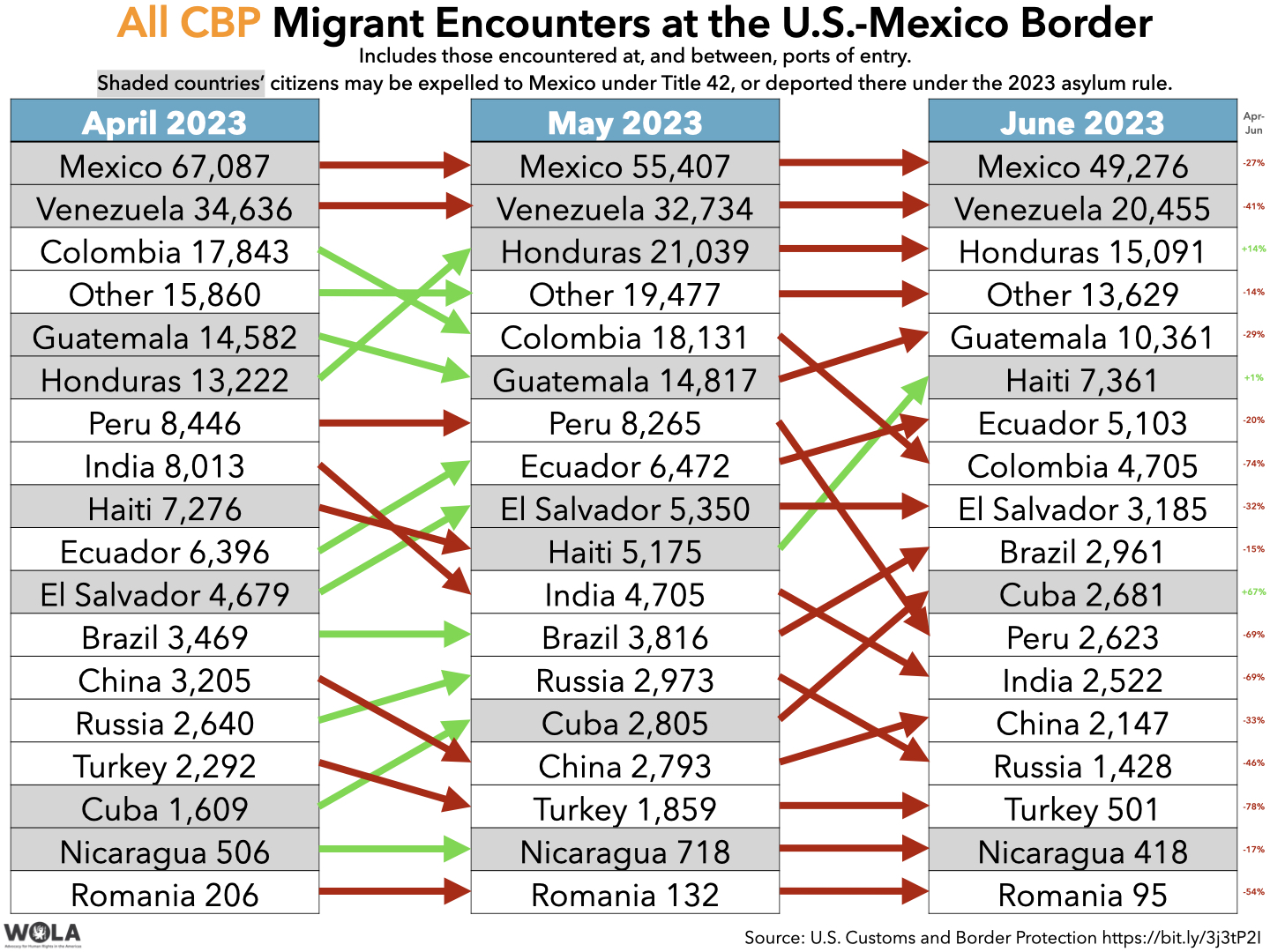

The data show a 30 percent drop in CBP’s encounters with migrants from May to June—from 206,702 to 144,571. That number combines people who were able to approach ports of entry (official border crossings), where they are processed by CBP’s Office of Field Operations, plus people who cross in the spaces between the ports of entry, where they are apprehended and processed by Border Patrol.

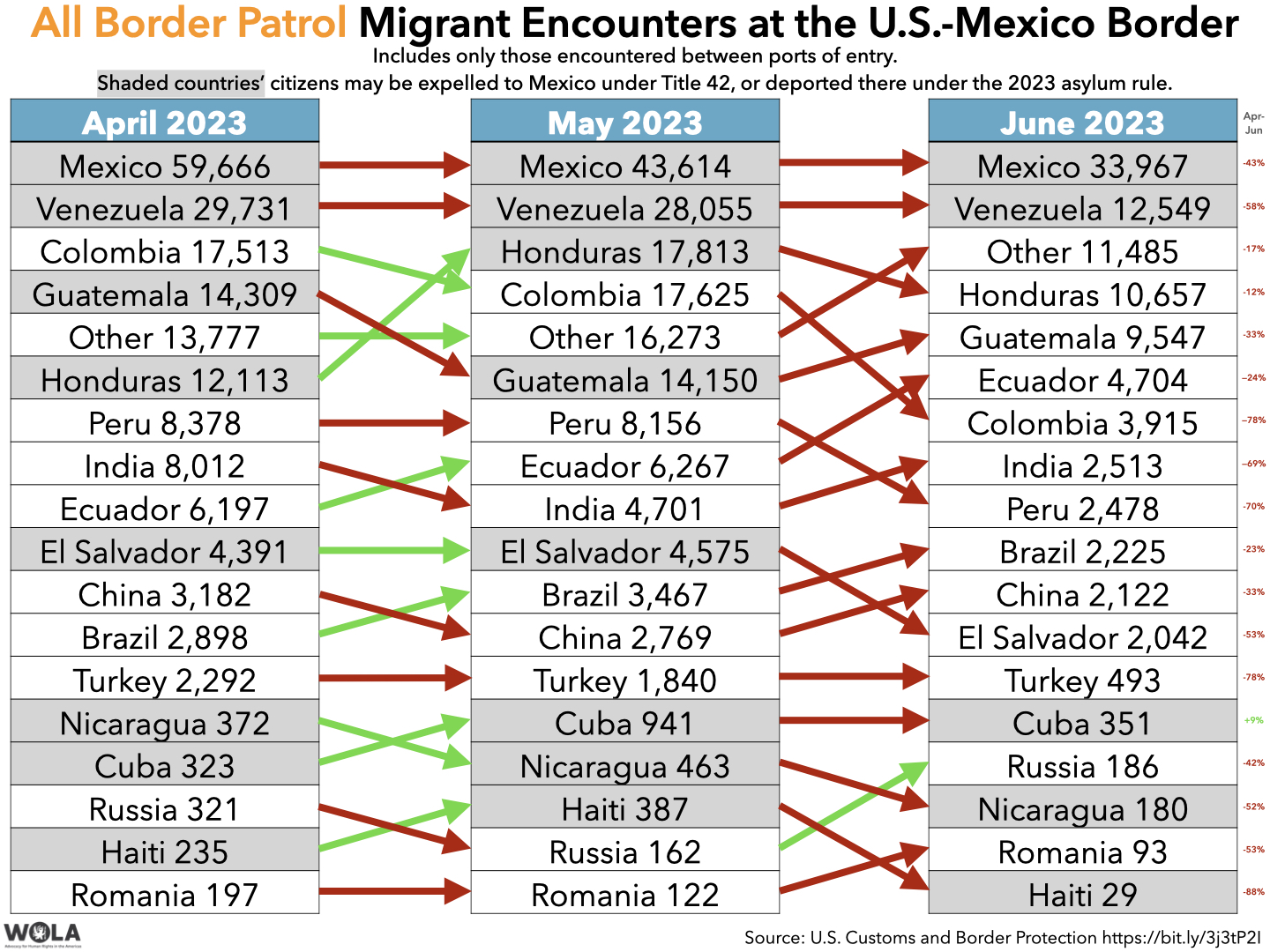

The number of migrant encounters in the latter category—people apprehended by Border Patrol—fell by 42 percent from May to June, from 171,387 to 99,545. This is the fewest since February 2021, the Biden administration’s first full month.

Nearly every nationality’s Border Patrol apprehensions declined, with Colombia (-78%), Turkey (-73%), and Peru (-70%) the nationalities with over 1,000 apprehensions that declined most sharply.

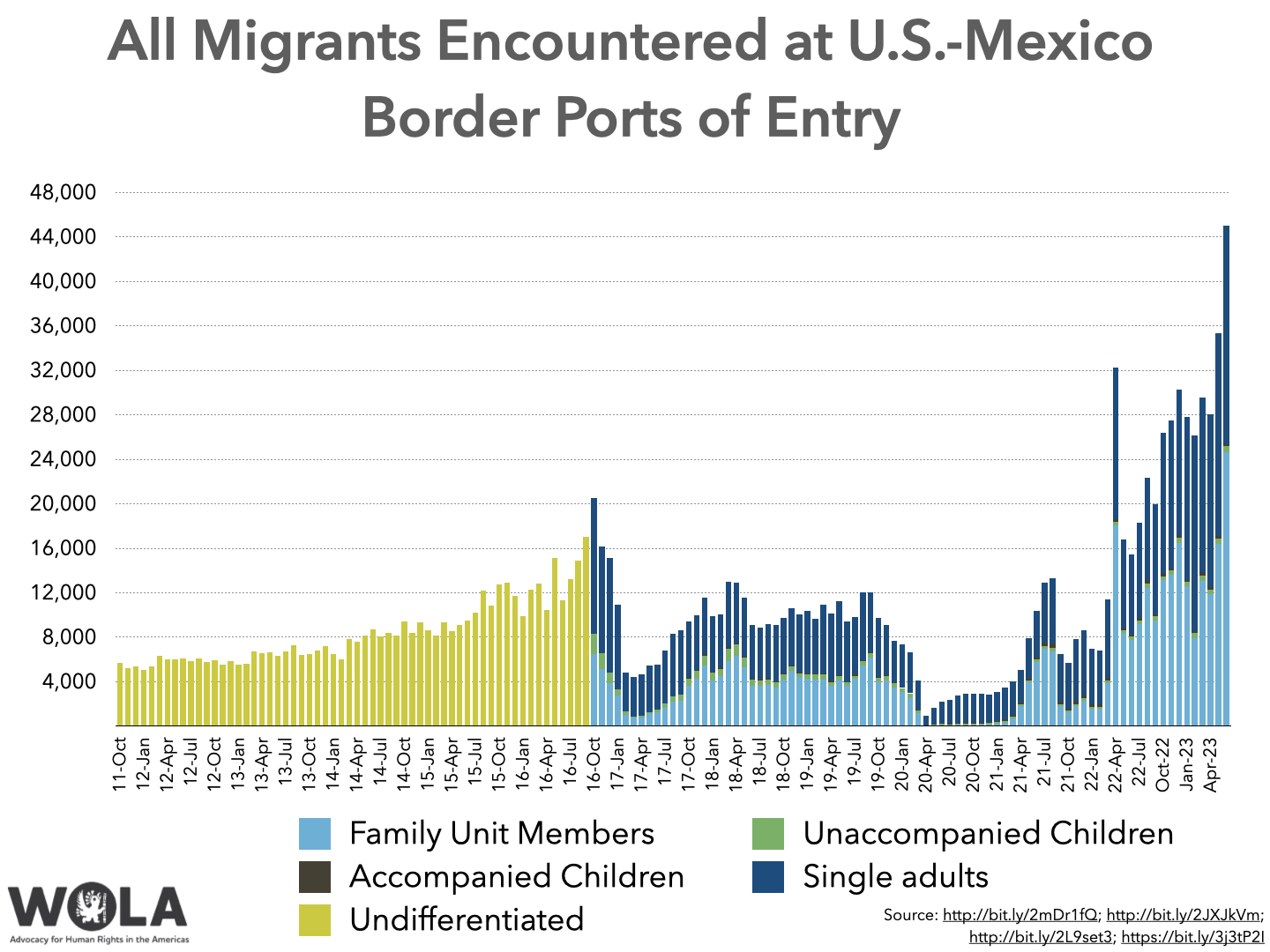

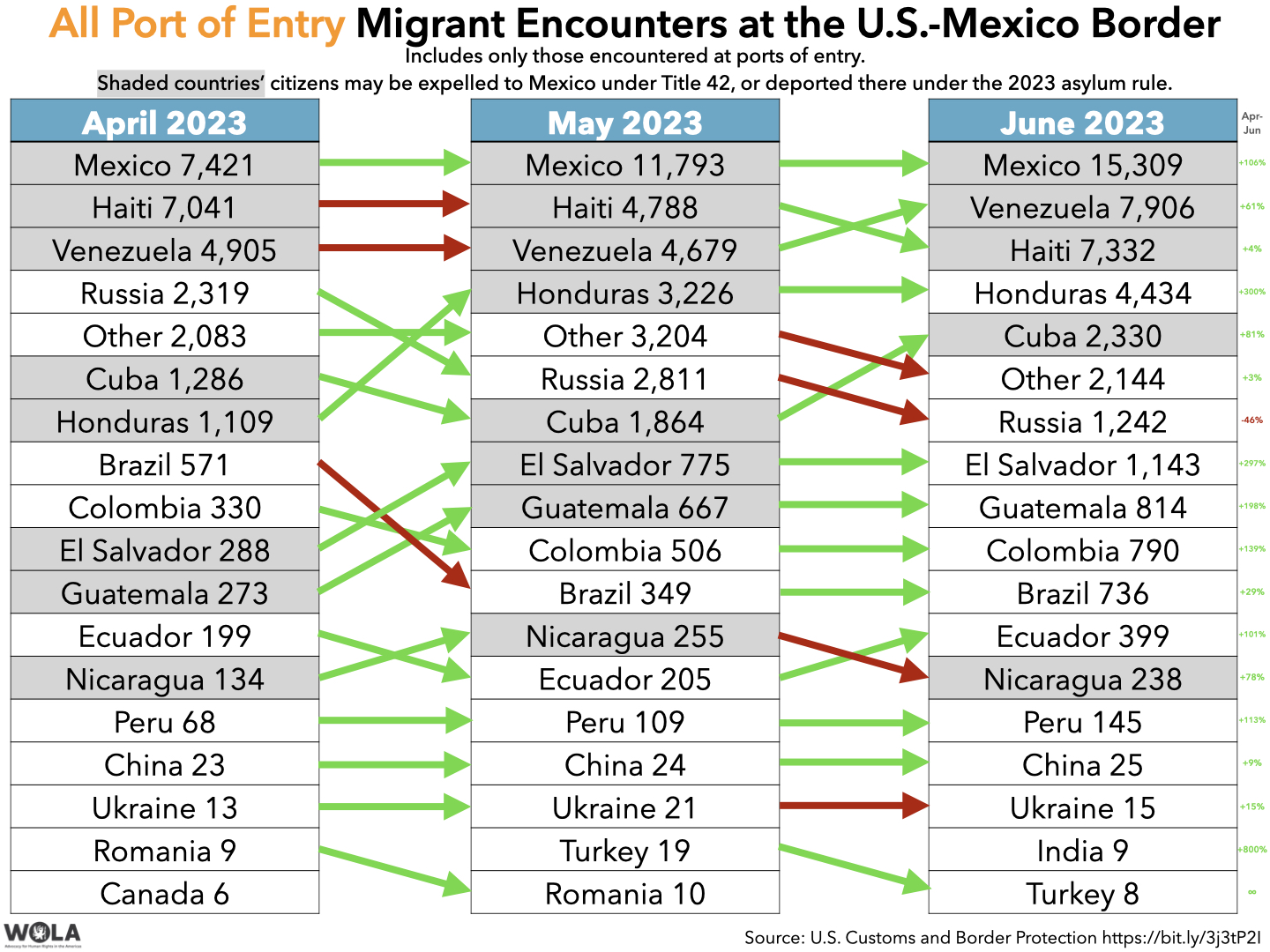

The reduction in Border Patrol encounters was partially offset by a 27 percent increase in the first category: migrants who were able to approach the ports of entry and present to CBP. The 45,026 people processed at the ports is almost certainly a record. It is more than 4 times the monthly average in fiscal year 2019 (10,500), the last full year before the pandemic hit.

The countries whose citizens reported to ports of entry in greatest numbers in June were Mexico, Venezuela, Haiti, Honduras, and Cuba. Nearly 100 percent of Haitians encountered anywhere at the border came to the ports (7,332 of 7,361 people).

The numbers show an unprecedented movement of migration—at least, of migrants who are seeking protection and wish to be apprehended—from between the ports of entry to the ports themselves.

Some of that is a result of the Biden administration’s tough new rule (discussed below) putting asylum out of reach for many who cross between the ports. Some of it is a result of a doubling, from the Title 42 period, of the number of daily appointments available at ports of entry for asylum seekers using the CBP One smartphone app. Of the 45,026 people who came to the ports of entry in June, “more than 38,000” (about 84 percent) had scheduled CBP One appointments.

Greater processing capacity at ports of entry adds an important degree of order to the asylum process at the border. The app, however, still has flaws. “People are getting appointments. People are using it. Then, of course, there are a lot of people who don’t have access to phones,” Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, director of the Sidewalk School, which works with migrants waiting to cross to the United States in Reynosa and Matamoros, told USA Today.

Wait times for appointments still last several weeks, which is untenable for those who face threats in Mexico. That is the case for many who, lacking appointments, are lined up for days at a time outside the DeConcini port of entry outside Nogales, Arizona. Still others are awaiting appointments in a massive, insecure, heat-ravaged tent encampment in Matamoros, along the river across from Brownsville, Texas. The human rights and security risks faced by migrants awaiting appointments in Mexican border cities is the topic of a July 12 report from Human Rights first, discussed below.

The tables here, covering April through June, combine migrants encountered both at and between the ports of entry.

From May to June, combining migrants at and between ports of entry:

We do not know what migration trends look like for the first half of July. However, the one country that reports migrant encounters in something like real time, Honduras, has suddenly seen its own migrant encounters increase to a record-setting pace. Honduran authorities registered 20,711 “irregular” migrants, 48 percent of them Venezuelan, during the first 16 days of July. That pace—1,294 migrants per day—is about one-third more than during the pre-Title 42 rush and sets Honduras on pace to smash its prior monthly high of 30,775 migrant registries (October 2022).

In Oakland on July 19, the U.S. District Court of the Northern District of California held a hearing on a lawsuit, brought by migrants’ rights defense organizations, challenging the Biden administration’s new restrictions on access to asylum. The American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of Northern California, Center for Gender and Refugee Studies, and National Immigrant Justice Center brought the suit on May 11, the day that the Biden administration terminated the Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy and imposed the new rule.

As discussed in numerous WOLA Border Updates in March through May, the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice “Circumvention of Legal Pathways” rule presumptively denies asylum, with some exceptions, to migrants who (a) fail to make an appointment at a port of entry, and (b) were not refused asylum in another country through which they passed en route to the United States. The rule went into effect on May 11, 2023 despite the submission of tens of thousands of comments—from human rights groups, UN and international agencies, members of Congress, and others—warning that it truncates the right to apply for asylum as spelled out in U.S. and international law.

On July 12, Human Rights First published a research report detailing abuse, threats, and other human rights and security risks suffered by migrants forced to wait in Mexican border towns—usually for CBP One smartphone app appointments—because it is no longer possible for them to approach a port of entry or cross the border to ask U.S. authorities to apply for asylum. It includes examples of kidnappings and assaults perpetrated in Mexico against migrants waiting for their CBP One appointments, among them:

a Venezuelan family kidnapped and tortured in Reynosa; a Honduran woman raped in Matamoros; a Central American man kidnapped and tortured in Reynosa; a Latin American woman kidnapped, trafficked and raped in Reynosa; a Venezuelan family kidnapped and the mother sexually abused in Reynosa; a Latin American family kidnapped and the mother raped in Reynosa; and a Haitian family that suffered an attempted kidnapping in Nogales when they arrived for their CBP One appointment.

Several parents in northern Mexico told Human Rights First “that they sleep in encampments with cable wires tied around their children for fear that while they sleep, their children will be abducted, abused, and potentially trafficked.”

Asylum seekers subjected to the new rule often end up in “expedited removal” proceedings, where they must defend their cases within days of apprehension, from jail-like CBP facilities, usually without counsel or even a decent amount of rest. Though U.S. government policy sets a maximum of 72 hours in CBP custody under normal conditions, CNN reported that asylum seekers in expedited-removal proceedings are routinely spending many more days than that while awaiting interviews with asylum officers. A spokesperson for the union of employees of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS, which includes asylum officers) called the process “frustrating.”

The July 19 hearing on the Biden administration rule was presided by District Judge Jon Tigar, an Obama appointee who, in 2019, struck down a Trump administration “asylum transit ban” that—though with fewer exceptions and no “CBP One” option—resembles the new rule. At the time, Tigar determined that the Trump rule contravened the right to seek asylum without regard to how a migrant entered the country, as laid out in Section 208 of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

At the hearing, Judge Tigar joked that he heard “2023 was going to be a big year for sequels,” Los Angeles Times reporter Hamed Aleaziz recounted on Twitter—an apparent reference to the earlier challenge to the Trump rule. “I wouldn’t call this a sequel, I would call it a remake,” the Justice Department attorney defending the rule reportedly replied.

Tigar is expected to issue his decision within a week. If he strikes down the Biden administration rule, he will stay his order for two weeks, as the administration requested, while it pursues appeals. It is difficult to predict whether the “transit ban” rule will remain in effect following those subsequent challenges.